The French Winawer Move by Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Los Angeles to Reykjavik

FROM LOS ANGELES CHAPTER 5: TO REYKJAVIK 1963 – 68 In July 1963 Fridrik Ólafsson seized a against Reshevsky in round 10 Fridrik ticipation in a top tournament abroad, Fridrik spent most of the nice opportunity to take part in the admits that he “played some excellent which occured January 1969 in the “First Piatigorsky Cup” tournament in games in this tournament”. Dutch village Wijk aan Zee. five years from 1963 to Los Angeles, a world class event and 1968 in his home town the strongest one in the United States For his 1976 book Fridrik picked only Meanwhile from 1964 the new bian- Reykjavik, with law studies since New York 1927. The new World this one game from the Los Angeles nual Reykjavik chess international gave Champion Tigran Petrosian was a main tournament. We add a few more from valuable playing practice to both their and his family as the main attraction, and all the other seven this special event. For his birthday own chess hero and to the second best priorities. In 1964 his grandmasters had also participated at greetings to Fridrik in “Skák” 2005 Jan home players, plus provided contin- countrymen fortunately the Candidates tournament level. They Timman showed the game against Pal ued attention to chess when Fridrik Benkö from round 6. We will also have Ólafsson competed on home ground started the new biannual gathered in the exclusive Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles for a complete a look at some critical games which against some famous foreign players. international tournament double round event of 14 rounds. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3

01-01 Cover - October 2020_Layout 1 18/09/2020 14:00 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Peter Wells.......................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine The acclaimed author, coach and GM still very much likes to play Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Online Drama .........................................................................................................8 Danny Gormally presents some highlights of the vast Online Olympiad Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Carlsen Prevails - Just ....................................................................................14 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Nakamura pushed Magnus all the way in the final of his own Tour 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Find the Winning Moves.................................................................................18 3 year (36 issues) £125 Can you do as well as the acclaimed field in the Legends of Chess? Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Opening Surprises ............................................................................................22 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 -

Galería De Maestros (37) Wolfgang Uhlmann En El Ajedrez La Defensa

Galería de Maestros (37) Wolfgang Uhlmann En el ajedrez la Defensa Francesa está ligada indisolublemente al alemán Wolfgang Uhlmann, (Dresde, 29 de marzo de 1935), que hoy cumple 76 años. “Cuando se juega bien La Defensa Francesa es una verdadera delicia, es siempre interesante y lleva a luchas extremadamente complejas” dice Uhlmann en el prólogo a su libro “Winning with the French”, donde analiza 60 de sus mejores partidas con su defensa predilecta, fruto de sus 40 años defendiéndola. El libro se publicó por primera vez en 1991 en alemán y luego en otros idiomas, desde 2006 existe la versión en castellano (Editorial Hispano Europea) Con ella ha derrotado entre otros a Robert Fischer, Leonid Stein, David Bronstein, Efim Geller, Robert Byrne, Isaac Boleslavsky, e infinidad de maestros. También fue un experto en la Defensa Gruenfeld y la Defensa India del Rey, pero su legado no fue tan importante como en la Defensa Francesa. Claro que no es el único maestro que aportó ideas importantes a esta defensa, de inmediato vienen a la memoria los nombres de Viktor Korchnoi, Mikhail Botvinnik, Aarón Nimzovich, y muchos otros, pero Uhlmann la jugó en exclusividad, su maestría era tal que el ex campeón del mundo Anatoly Karpov, en la plenitud de su carrera, lo tuvo como su consejero en la Defensa Francesa. Era el número 1 de la extinta RDA, o Alemania Oriental, de la que fue campeón nacional en 11 ocasiones, desde 1954 a 1986, y a la que representó en 11 olimpiadas, casi todas como primer tablero, desde Moscú 1956 hasta Novi Sad 1990, esa fue la última vez en que Alemania se presentó separada a una cita internacional. -

The Nemesis Efim Geller

Chess Classics The Nemesis Geller’s Greatest Games By Efim Geller Quality Chess www.qualitychess.co.uk Contents Publisher’s Preface 7 Editor’s Note 8 Dogged Determination by Jacob Aagaard 9 Biographical Data & Key to symbols used 20 1 In search of adventure, Geller – Efim Kogan, Odessa 1946 21 2 Is a queen sacrifice always worth it? Samuel Kotlerman – Geller, Odessa 1949 25 3 A bishop transformed, Tigran Petrosian – Geller, Moscow 1949 29 4 Miniature monograph, Geller – Josif Vatnikov, Kiev 1950 31 5 Equilibrium disturbed, Mikhail Botvinnik – Geller, Moscow 1951 35 6 Blockading the flank, Mikhail Botvinnik – Geller, Budapest 1952 40 7 A step towards the truth, Geller – Wolfgang Unzicker, Stockholm 1952 44 8 The cost of a wasted move, Harry Golombek – Geller, Stockholm 1952 47 9 Insufficient compensation? Geller – Herman Pilnik, Stockholm 1952 49 10 Black needs a plan... Geller – Robert Wade, Stockholm 1952 51 11 White wants a draw, Luis Sanchez – Geller, Stockholm 1952 53 12 Sufferings for nothing, Geller – Gideon Stahlberg, Stockholm 1952 55 13 A strong queen, Geller – Gedeon Barcza, Stockholm 1952 58 14 The horrors of time trouble, Geller – Laszlo Szabo, Stockholm 1952 60 15 Seizing the moment, Geller – Paul Keres, Moscow 1952 62 16 Strength in movement, Geller – Miguel Najdorf, Zurich 1953 66 17 Second and last... Max Euwe – Geller, Zurich 1953 70 18 Whose weakness is weaker? Mikhail Botvinnik – Geller, Moscow 1955 74 19 All decided by tactics, Vasily Smyslov – Geller, Moscow (7) 1955 78 20 Three in one, Geller – Oscar Panno, Gothenburg -

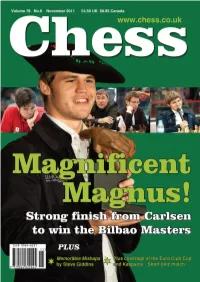

CHESS-Nov2011 Cbase.Pdf

November 2011 Cover_Layout 1 03/11/2011 14:52 Page 1 Contents Nov 2011_Chess mag - 21_6_10 03/11/2011 11:59 Page 1 Chess Contents Chess Magazine is published monthly. Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial Editor: Jimmy Adams Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in chess 4 Acting Editor: John Saunders ([email protected]) Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Readers’ Letters ([email protected]) You have your say ... Basman on Bilbao, etc 7 Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Sao Paulo / Bilbao Grand Slam 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 The intercontinental super-tournament saw Ivanchuk dominate in 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Brazil, but then Magnus Carlsen took over in Spain. 8 3 year (36 issues) £125.00 Cartoon Time Europe Oldies but goldies from the CHESS archive 15 1 year (12 issues) £60.00 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Sadler Wins in Oslo 3 year (36 issues) £165.00 Matthew Sadler is on a roll! First, Barcelona, and now Oslo. He annotates his best game while Yochanan Afek covers the action 16 USA & Canada 1 year (12 issues) $90 London Classic Preview 2 year (24 issues) $170 We ask the pundits what they expect to happen next month 20 3 year (36 issues) $250 Interview: Nigel Short Rest of World (Airmail) Carl Portman caught up with the English super-GM in Shropshire 22 1 year (12 issues) £72 2 year (24 issues) £130 Kasparov - Short Blitz Match 3 year (36 issues) £180 Garry and Nigel re-enacted their 1993 title match at a faster time control in Belgium. -

Yearbook.Indb

PETER ZHDANOV Yearbook of Chess Wisdom Cover designer Piotr Pielach Typesetting Piotr Pielach ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2015 by Chess Evolution Yearbook of Chess Wisdom Copyright © 2015 Chess Evolution All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. isbn 978-83-937009-7-4 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Chess Evolution ul. Smutna 5a, 32-005 Niepolomice, Poland e-mail: [email protected] website: www.chess-evolution.com Printed in Poland by Drukarnia Pionier, 31–983 Krakow, ul. Igolomska 12 To my father Vladimir Z hdanov for teaching me how to play chess and to my mother Tamara Z hdanova for encouraging my passion for the game. PREFACE A critical-minded author always questions his own writing and tries to predict whether it will be illuminating and useful for the readers. What makes this book special? First of all, I have always had an inquisitive mind and an insatiable desire for accumulating, generating and sharing knowledge. Th is work is a prod- uct of having carefully read a few hundred remarkable chess books and a few thousand worthy non-chess volumes. However, it is by no means a mere compilation of ideas, facts and recommendations. Most of the eye- opening tips in this manuscript come from my refl ections on discussions with some of the world’s best chess players and coaches. Th is is why the book is titled Yearbook of Chess Wisdom: it is composed of 366 self-suffi - cient columns, each of which is dedicated to a certain topic. -

Brekke the Chess Saga of Fridrik Olafsson

ØYSTEIN BREKKE | FRIDRIK ÓLAFSSON The Chess Saga of FRIÐRIK ÓLAFSSON with special contributions from Gudmundur G. Thórarinsson, Gunnar Finnlaugsson, Tiger Hillarp Persson, Axel Smith, Ian Rogers, Yasser Seirawan, Jan Timman, Margeir Pétursson and Jóhann Hjartarson NORSK SJAKKFORLAG TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by President of Iceland, Guðni Th. Jóhannesson ..................4 Preface .........................................................5 Norsk Sjakkforlag Fridrik Ólafsson and his Achievements by Gudmundur G. Thorarinsson .....8 Øystein Brekke Haugesgate 84 A Chapter 1: 1946 – 54 From Childhood to Nordic Champion .............10 3019 Drammen, Norway Mail: [email protected] Chapter 2: 1955 – 57 National Hero and International Master ...........42 Tlf. +47 32 82 10 64 / +47 91 18 91 90 www.sjakkforlag.no Chapter 3: 1958 – 59 A World Championship Candidate at 23 ..........64 www.sjakkbutikken.no Chapter 4: 1960 – 62 Missed Qualification in the 1962 Interzonal ........94 ISBN 978-82-90779-28-8 Chapter 5: 1963 – 68 From Los Angeles to Reykjavik ..................114 Authors: Øystein Brekke & Fridrik Ólafsson Chapter 6: 1969 – 73 The World’s Strongest Amateur Player ............134 Design: Tommy Modøl & Øystein Brekke Proof-reading: Tony Gillam & Hakon Adler Chapter 7: 1974 – 76 Hunting New Tournament Victories ..............166 Front page photo: Chapter 8: 1977 – 82 Brilliant Games & President of FIDE ..............206 Fridrik in the Beverwijk tournament 1961. (Harry Pot, Nationaal Archief) Chapter 9: 1983 – 99 Fridrik and the Golden Era of Icelandic Chess ....246 Production: XIDE AS & Norsk Sjakkforlag Chapter 10: 2000 – An Honorary Veteran Still Attacking ..............262 Cover: XIDE AS & Norsk Sjakkforlag Printing and binding: XIDE AS Games in the Book ................................................282 Paper: Multiart Silk 115 gram Opening index ....................................................284 Copyright © 2021 by Norsk Sjakkforlag / Øystein Brekke Index of opponents, photos and illustrations ...........................285 All rights reserved. -

Der Spiegel 04

Pachman, Luděk (11.05.1924 - 06.03.2003) Czech IM (1950) and Grandmaster (1954), leading opening theorist and author of 80 books and a journalist who was living later in West Germany. Editor of the FIDE magazine from the late 1950s to the mid 1960s. Born in the small Czech town of Bela pod Bezdezem, Luděk Pachman went on to become one of the leading players of his generation. He honed his chess skills in Prague during World War II under the expert tutelage of World Champion Alexander Alekhine. Pachman's first serious event at the age of 19 was the 1943 Prague tournament, won by Alekhine. Seven times Czechoslovakian Champion in 1946, 1953, 1957, 1959, 1961, 1963 and 1966. Pachman won also (West) German Championship in 1978 Winner at Arbon SASB 1946 (shared with Yanovsky (best tie-break), and Opocensky, ahead of 4. O’Kelly) and Arbon SASB 1949 (ahead of Wade), Bucharest 1949, Mar del Plata GM 1959 (together with Miguel Najdorf, ahead of joint 3./4. Bobby Fischer and Borislav Ivkov), Santiago de Chile 1959 (shared with Ivkov, ahead of 3. Pilnik, 4.-7. Sanchez, Sanguineti, and Fischer): ➢ Fischer and Pachman were sparring with each others' opening preparation for the Santiago. The amicable pair had toured just a couple of weeks previously, after the Mar del Plata 1959 tournament wrapped up to enjoy a short vacation. Lima, Peru 1959 (shared again with Ivkov), Sarajevo (Bosna) 1960 (shared with Stojan Puc who had won the inaugural event at Sarajevo in 1957, twelve players including 8./9. Bent Larsen, Vasja Pirc) and Sarajevo (Bosna) 1961 (shared with Svetozar Gligoric), Marianske Lazne 1960, Graz, Austria 1961, Athens (Acropolis, first event of the series) 1968, and Reggio Emilia 1975-76. -

CR1969 04.Pdf

APRIL 1969 WINNER - - AT \ MALAGA ( S u plge 100) . ,1 ;# Subscription .ate ONE YEAR 57.50 e '---' wn 789 PAGES: 7 1/, by 9 inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 ideo variations 1704 practical variations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all variations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A. HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr. Max Euwe, Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch, and many other noted authorities This latest and immense work, the most exhaustive of its kind, e.x· plains in encyclopedic detail the fi ne points of all ope(Jings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not left hanging in mid·position with the query: What happens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. First come the moves with footnotes leading to the key position. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low pertinent observations, illustrated by "Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper. handsome print. Practical and Supplementary Va ri ations, well annotated, exemplify the spacious paging and all the effective possibilities. Each line is appraised: +, - or = . The large format-71/ z x 9 inches- is designed for ease 0,[ read· other appurtenances of exquis ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shu £fling of page ~ ite book-making combine to between the principal lines and the respective comments. Clear. make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation.identify. ing diagrams are other plus features. chess books! In addition to all else, this book contains 439 complete games- a golden treasury in itself! ORDER FROM CHESS REVIEW 1------------------- ------ - --I I Please send me Chess Opel/il/gs: Theory (Jnd Practice at $12.50 I Name ............ -

Chess Books! in Addition to All Else, This Book Contains 439 Complete Games- a Golden Treasury in Itself!

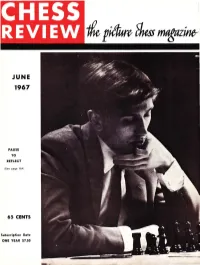

JUNE 1967 PAUSE TO REfLECT 6S CENTS Subscription Rat~ ONE YEAR $7.50 e UJI 789 PAGES: 7'/2 by 9 inches, clothbound 221 diagrams 493 idea variations 1704 practical variations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to aU variations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A. HOROWITZ in colla boration with Former World Champion, Dr. Max Euwe, Ernest Gruen/eld, Hans Kmoch, and many ot her noted authorities This latest and immense work, the most exhaustive of its kind, ex· plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not left hanging in mid-position with the query : What happens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. First come the moves with footnotes leading to the key position. Then fol BIBLIOPHILES! low pertinent observations, illustrated by " Idea Variations. " Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print. Practical and Supplementary Variations, well annotated, exemplify the spacious paging and all the effective possibilities. Each line is appraised: +, - or =. The large format- 71!2 x 9 inches- is designed for ease of read· other appurtenances of exquis ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuffling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal lines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation-identify. ing diagrams are other plus features. chess books! In addition to all else, this book contains 439 complete games- a golden treasury in itself! 1------------------ - - - -- --- - -- - I I Please send me ehas Openings: Theory and Practice at 812.50 I I Name .. -

Chess Autographs

Chess Autographs Welcome! My name is Gerhard Radosztics, I am living in Austria and I am a chess collector for many years. In the beginning I collected all stuff related to chess, especially stamps, first day covers, postmarks, postcards, phonecards, posters and autographs. In the last years I have specialised in Navigation Autograph Book Old chess postcards (click on card) A - M N - Z Single Chess autographs Links Contact On the next pages you can see a small part of my collection of autographs. The most of them are recognized, if you can recognize one of the unknown, please feel free to e-mail me. Note: The pages are very graphic intensive, so I ask for a little patience while loading. http://www.evrado.com/chess/autogramme/index.shtml[5/26/2010 6:13:18 PM] Autograph Book Autograph Book pages » back to previous page Page 1 - Introduction Page 18 - Marshall Page 2 - Aljechin Page 19 - Spielmann Page 3 - Lasker Page 19a - Capablanca Page 4 - Gruenfeld Page 20 - Canal Page 5 - Rubinstein Page 21 - Prokes Page 6 - Monticelli Page 22 - Euwe Page 7 - Mattisons Page 23 - Vidmar Page 8 - Asztalos Page 24 - Budapest 1948 Page 9 - Kmoch Page 25 - HUN - NED 1949 Page 10 - Gilg Page 25a - HUN - YUG 1949 Page 11 - Tartakover Page 26 - Budapest 1959 Page 12 - Nimzowitsch Page 26a - Budapest 1959 Page 13 - Colle Page 27 - Olympiad Leipzig Page 14 - Brinckmann Page 28 - Olympiad Leipzig Page 15 - Yates Page 29 - Budapest 1961 Page 16 - Kagan Page 30 - Spart.-Solingen 76 Page 17 - Maroczy http://www.evrado.com/chess/autogramme/autographindex.htm[5/26/2010 6:13:20 PM] Autogramme - Turniere - Namen Tournaments: » back to previous page 1 Sliac 1932 8 Dubrovnik 1950 15 Nizza 1974 2 Podebrady 1936 9 Belgrad 1954 16 Biel 1977 3 Semmering - Baden 1937 10 Zinnowitz 1967 17 Moskau 1994 4 Chotzen 1942 11 Polanica Zdroj 1967 18 Single autographs 5 Prag 1942 - Duras Memorial 12 Lugano 1968 19 World Champions Corr. -

CHESS REVIEW Rhi "Au., CHI N MAO""'" Vol Un'e 31 Number 10 October 1S63 EDITED &

OCTOBER 1963 U. S. CHAMPION SPLURGES IN SWISSES 60 CENTS S"bscrlptiolt Rat. ONE YEAR S6.50 1 White to move and win 2 Black t o move and win ThIs first puzzler is one Whereas your opponent real test. Black has a Pawn was t hreatening nothing of THE WIN' S THE THING and fair developm ent. But import in the last example, his lUng is uncastled, and he has your Rool;: u nder fire In each of these ten positions, there is a sharp therein lies your telling lIere. How to save the Rook way of winning decisively. It is waiting and ready advantage. There's your and win is t he problem. In clue; the rest is up to you such p ressure, you may be for you - if you are ready for it. Score ten cor - find the winning move and compelled to find the only run off enough varlatlolls move. It works so In aCi ual rect solutions fo r an excellent rating; eight for good; to prove it wins conclusively. games most of the time. six for fair. Solutions o'n page 319. That is all. Work it now! 3 White to move and w in 4 Black to move and win 5 W hite t o move and win 6 Black to move and win Here li kewise you have a It goes wlthout saying in Here your Pawns are in a This problem [Josition is Rook under fire. 'Tis some this example that an end· sad state of disarray, a nd just exactly thn - and it thing, nothing; but you may game will be bad for you.