High School Comprehensive Resource Packet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Tells Your Story?: Intersections of Power, Domesticity, and Sexuality Relating to Rap and Song in the Musical Hamilton

WHO TELLS YOUR STORY?: INTERSECTIONS OF POWER, DOMESTICITY, AND SEXUALITY RELATING TO RAP AND SONG IN THE MUSICAL HAMILTON By Tia Marie Harvey A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Musicology—Master of Arts 2019 ABSTRACT WHO TELLS YOUR STORY?: INTERSECTIONS OF POWER, DOMESTICITY, AND SEXUALITY RELATING TO RAP AND SONG IN THE MUSICAL HAMILTON By Tia Marie Harvey In January 2015, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton: An American Musical premiered at The Public Theater in New York City. Later that year it moved to Broadway with an engagement at the Richard Rodgers Theater, followed by productions in Chicago and London. Commercially successful and critically acclaimed, Hamilton continues to hold significant cultural relevance in 2019. As a result of this musical’s cultural significance, it has the ability to communicate positive, but also limiting, aspects of our society. In this thesis, I examine the concept of rap as a musical language of power. To do this, I assert that characters in Hamilton who have power, and particularly when expressing that power, do so through rap. In contrast, when characters don’t have power, or are entering realms of the powerless (i.e. spaces gendered female), they do so through lyrical song. In chapter 1, I set up the divide between rap and song as it primarily translates among male characters and class. Chapter 2 is focused on the domestic sphere, and in chapter 3 I discuss sexuality. In the conclusion of this thesis, I revisit the character of Eliza and explore the perceived power of her role as storyteller and the way in which the themes I discuss illuminate many missed opportunities to present an interpretation of America’s founding that is truly revolutionary. -

Bullseye with Jesse Thorn Is a Production of Maximumfun.Org and Is Distributed by NPR

00:00:00 Music Music Gentle, trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:01 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:11 Jesse Host I’m Jesse Thorn. It’s Bullseye! Thorn 00:00:14 Music Music “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team plays. A fast, upbeat, peppy song. Music plays as Jesse speaks, then fades out. 00:00:20 Jesse Host Lin-Manuel Miranda grew up in a working-class neighborhood, north of Harlem. He went to a fancy school for gifted kids, on the Upper East Side. He went to college at Wesleyan, and not long after he graduated, he had a hit Broadway musical— [“Huddle Formation” fades out to be replaced with “In the Heights”.] In the Heights. 00:00:34 Clip Clip “In the Heights” from the Broadway musical In the Heights plays. ENSEMBLE: In the Heights I can’t survive without café USNAVI: I serve café ENSEMBLE: 'Cause tonight... [Music fades out as Jesse speaks] 00:00:41 Jesse Host He’s also the creator and star of Hamilton: the award-winning, massively influential musical about the founding f—well, you know what. This is a little silly. I’m explaining the plot of Hamilton on NPR. You know what Hamilton is. These days, Lin-Manuel is in a spot where not many artists find themselves. He can do pretty much whatever he wants! He can take on almost any project. -

Commonlit | Lin-Manuel Miranda

Name: Class: Lin-Manuel Miranda By Jessica McBirney 2017 Lin-Manuel Miranda is best known for creating and starring in the Broadway musicals Hamilton and In the Heights. He has received the highest honors in theater, television, and music for his talents and innovation in the arts. In this informational text, Jessica McBirney discusses Miranda’s life and career as an artist. As you read, take notes on the development of Miranda’s career in the entertainment industry. [1] Lin-Manuel Miranda is an American writer and actor who has risen to popularity in recent years for his unique combination of hip-hop and Broadway-style music to tell stories. His two most popular musicals, In The Heights and Hamilton, both purposely feature a diverse range of actors and characters from different backgrounds. Formative Childhood Lin-Manuel Miranda often cites his childhood years as a source of inspiration for his work. He was born on January 16, 1980, in Washington "Lin-Manuel Miranda, 2016" by Nathan Hughes Hamilton is Heights, a majority-Latino neighborhood in Upper licensed under CC BY 2.0. Manhattan, New York. His parents were of mostly Puerto Rican descent; his mother worked as a clinical psychologist, and his father was a Democratic Party consultant who advised New York City’s mayor in political situations. Growing up in Washington Heights gave Miranda a love for music, especially hip-hop. For one month each summer, Miranda also went to stay with his grandparents in Puerto Rico. As a teenager, he wrote jingles for advertisements. Miranda started attending Wesleyan University in 1998, where he co-founded a hip-hop comedy group called Freestyle Love Supreme. -

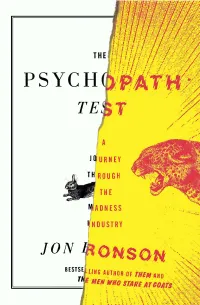

Jon Ronson the Psychopath Test

A JO URNEV THROUGH THE JON ·-.. ON SON ··.·· UNG_ A_�T��_R_-=_Of TH�M===AN . :�;;�� D .._ __ .: ·=== ·-: __ ;;_.:.;;�::���;�\{ ·MEN WHO · $TA Rt AT IJOJI(S-:::-;:-,,··\t=:(ljfi;, lb======j . l ._:,: : \,\ · _ 1 1 I ·,,.:\ >S::.���l�l THE PSYCHOPATH TEST A Journey Through the Madness Industry JON RONSON Riverhead Books A member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Rew York 2011 RIVERHEAD BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA · Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eg)inton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Onrario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Lrd) ' Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Auslralia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, II Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017,1ndia • Penguin Group (NZ). 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL. England Copyright© 2011 by Jon Ronson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do nol participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author's rights. Purchase only authorized editions. Published simultaneously in Canada Photo credits: p. -

Read the Complete Playbill for Creations of a Caged Bird, Vol. 2

◎ ABOUT THIS PROJECT ◎ This video is the culminating result of one of Shining Light’s most expansive programs, the Collaborative Arts Project. Incarcerated participants are invited to encourage and inspire thousands of their peers in prisons across the country through original artwork, created from prompts like “What I Wish You Knew” and “Hope In Hardship.” Pieces are then selected to be produced by professional artists/filmmakers and curated in a 60-minute video with supportive messages from public figures and former participants of the SL community who have since been released. These videos are then sent back into prisons for an uplifting facility-wide experience. The final production “Creations of a Caged Bird, volume 2” will be distributed to partnering prisons to be played on TVs and individual electronic tablets in: ○ Pennsylvania ○ North Dakota ○ Ohio ○ Cook County Jail system (Chicago) ○ South Carolina ○ Rikers Island Jails (NYC) ◎ RUN OF SHOW ◎ ● “Man Up” p. 4 ● “Caught in the Silence” p. 9 ● “Reaching Out” p. 5 ● “Speaking to Society & p. 10 ● “What I Wish You Knew” p. 6 the Powers that Be” ● “Our Journey” p. 7 ● “Jump into your Destiny” p. 11 ● “My Life” p. 8 ● “Hope in Hardship” p. 12 ● “Caught in the Silence” p. 9 ● “Time in Heaven” p. 14 ◦ Artist Bios: p. 15 - 21 ALL PIECES WERE WRITTEN BY PEOPLE INCARCERATED IN PENNSYLVANIA A REFLECTION FROM ONE OF OUR CURRENT PARTICIPANTS: It reminded me that there are many forms of incarceration- physical/mental. Also- pain is pain. It isn't about your ethnicity, or the language you speak, or rich or poor...pain is universal. -

“America, You Great Unfinished Symphony”

“America, You Great Unfinished Symphony” Hamilton: An American Musical and its Role in Questioning the Cultural Hegemony of the Foundation Myth of the United States of America Master’s Thesis North American Studies University of Leiden Anneke van Hees S1153609 July 6, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. S.A. Polak Second Reader: Dr. S. Moody 2 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1: Musical Theater History .................................................................................. 15 Chapter Two: Founders Chic History ................................................................................ 23 Chapter Three: Hamilton’s Origin .................................................................................... 31 Chapter Four: Hamilton’s Text ......................................................................................... 38 Conclusion: History Has Its Eyes on You .......................................................................... 65 3 Introduction On November 18th, 2016, Vice President-elect Mike Pence was in the audience, accompanied by some younger family members. His presence alone elicited a range of responses. From a standing ovation after the line “Immigrants, we get the job done” (Miranda and McCarter, Hamilton the Revolution 121) to booing the Vice-President elect as he tried to leave after the show was done. It was at that point that Brandon Victor Dixon, who had played Aaron Burr, asked -

Why 'Hamilton' Has Heat

Why ‘Hamilton’ Has Heat By ERIK PIEPENBURG UPDATED June 12, 2016 http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/08/06/theater/20150806-hamilton- broadway.html “Hamilton,” the mega-buzzy bio-musical about Alexander Hamilton and the founding fathers, opened to glowing accolades unlike any in memory. It received 11 Tony Awards, including best musical, and 16 Tony nominations, the most nominations in Broadway history. It won the Pulitzer Prize and a Grammy Award. In his review, Ben Brantley writes: “Yes, it really is that good.” It’s one of the most talked about Broadway shows since “The Book of Mormon” in 2011. Why? It’s a theatrical rarity: a critically acclaimed work, written by a young composer, that’s making a cultural impact far beyond Broadway’s 40 theaters. That it’s told through the language and rhythms of hip-hop and R&B — genres that remain mostly foreign to the musical theater tradition — has put it in contention to redefine what an American musical can look and sound like. As Mr. Brantley wrote in his review of the show Off Broadway, the songs in “Hamilton” could be performed “more or less as they are by Drake or Beyoncé or Kanye.” Ethel Merman it ain’t. So what’s the story behind a show that’s become a Broadway must-see with no marquee names, no special effects and almost no white actors? Here, in six snapshots, is an explanation of why “Hamilton” is a big deal. It’s a Genuine Smash “Hamilton” is on track to become one of the biggest critical and commercial hits in Broadway history. -

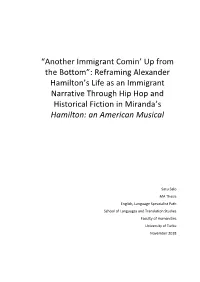

Another Immigrant Comin' up from the Bottom

“Another Immigrant Comin’ Up from the Bottom”: Reframing Alexander Hamilton’s Life as an Immigrant Narrative Through Hip Hop and Historical Fiction in Miranda’s Hamilton: an American Musical Satu Salo MA Thesis English, Language Speacialist Path School of Languages and Translation Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Turku November 2018 Turun yliopiston laatujärjestelmän mukaisesti tämän julkaisun alkuperäisyys on tarkastettu Turnitin OriginalityCheck -järjestelmällä. TURUN YLIOPISTO Kieli- ja käännöstieteiden laitos / Humanistinen tiedekunta SALO, SATU: “Another Immigrant Comin’ Up from the Bottom”: Reframing Alexander Hamilton’s Life as an Immigrant Narrative Through Hip Hop and Historical Fiction in Miranda’s Hamilton: an American Musical Tutkielma, 88 s. 10 liites. Englannin kieli, Kieliasiantuntijan Opintopolku Lokakuu 2018 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Tutkielmani tarkastelee Lin-Manuel Mirandan musikaalin Hamilton: An American Musical (2016) librettoa maahanmuuttokysymysten näkökulmasta. Musikaali yhdistää kerronnassaan hip hop musiikkia ja historiallista fiktiota, joten tutkielmani tarkastelee miten nämä ainesosat vaikuttavat musikaalin kerrontaan. Pro Gradu väittää, että Hamilton esittää päähenkilönsä Alexander Hamiltonin elämäntarinan maahanmuuttotarinana, joka uudelleenrakentaa Yhdysvaltain perustusmyytin maahanmuuttopositiiviseksi kertomukseksi hip hop-musiikin sekä historiallisen kaunokirjallisen kerronnan kautta. Pro Gradu tarkastelee aluksi hip hop tutkimuksen -

International Viewbook

TO BE THE BEST, TRAIN WITH THE BEST! For more than 50 years, AMDA has been devoted to training the actor, singer and dancer for stage, film and television. AMDA has launched some of the most successful global careers of performers in theatre, film, television and dance. That’s because aspiring actors, singers and dancers from all over the world receive world-class training at AMDA. AMDA has two campuses—one in each of the entertainment capitals of the world: Los Angeles and New York City. AMDA College of the Performing Arts, located in the heart of Hollywood, offers Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) and Associate of Occupational Studies (AOS) degrees. The American Musical and Dramatic Academy, located in the prestigious Upper West Side of Manhattan, offers professional certificate programs with an option to apply to the AMDA Los Angeles campus to complete a BFA degree. 1 AMDA Facts and Figures Founded in 1964 as a musical theatre school emerging from the vibrant Manhattan arts scene in New York City Opened its Los Angeles campus located in the heart of Hollywood in 2003 A private, nonprofit institution of higher education Accredited by the National Association of Schools of Theatre (NAST) and licensed to operate by the states of New York and California Ranked #4 on Playbill Magazine’s list of colleges with the greatest number of graduates on Broadway in the 2018-19 season and #6 on the Niche.com list of Best Colleges for Performing Arts in America Four distinct BFA degree programs, three AOS degree programs, and three professional conservatory certificate programs allow students to choose their paths to success in the performing arts Partial financial support to approximately 95% of enrolled students, including international students Two Great Locations - New York City and Los Angeles are two of the most culturally and ethnically diverse cities in the United States. -

S O U T H F L O R I D a G a Y N E W S LGBT ATHLETES FACE THEIR MOST

local name global coverage May 31, 2017 vol. 8 // issue 22 south florida gay news OUTGAMES DISASTER LGBT ATHLETES FACE THEIR MOST UNEXPECTED HURDLE YET EQUALITY MARCH FOR NANCY PELOSI VISITS UNITY AND PRIDE THE PRIDE CENTER PAGE 14 PAGE 16 SOUTHFLORIDAGAYNEWS SOFLAGAYNEWS SFGN.COM NEWS highlight SouthFloridaGayNews.com Mayor Jack Seiler at Fort Lauderdale’s Memorial Day Ceremony. Photo Credit: Fort Lauderdale, Facebook. May 31 2017 • Volume 8 • Issue 22 2520 N. Dixie Highway • Wilton Manors, FL 33305 Phone: 954-530-4970 Fax: 954-530-7943 Publisher • Norm Kent [email protected] Chief Executive Offi cer • Pier Angelo Guidugli Associate Publisher / Executive Editor • Jason Parsley [email protected] Editorial Art Director • Brendon Lies [email protected] Designer • Charles Pratt Designer • Max Kagno Associate Editor • Jillian Melero [email protected] Digital Content Director • Brittany Ferrendi [email protected] Arts/Entertainment Editor • JW Arnold [email protected] Social Media Manager • Tucker Berardi LGBT VETS BOYCOTT FORT LAUDErdale’s meMORIAL DAY CEREMONY [email protected] Anti-gay minister’s invitation causes backlash Food/Travel Editor • Rick Karlin Gazette News Editor • Michael d'Oliveira Michael d’Oliveira HIV Editor • Sean McShee Senior Photographer • J.R. Davis [email protected] Senior Features Correspondents he invitation of Dr. Jerry Newcombe to homosexuality. But He did when He to address the dangers of Muslims who Jesse Monteagudo • Tony Adams speak at Fort Lauderdale’s Memorial condemned pornea (from which we get the commit terrorism. “A born-again Christian Correspondents TDay ceremonies caused the Gold Coast word pornography). In Matthew 15:19, Jesus would not have done those things,” he Dori Zinn • Andrea Richard • Donald Chapter of American Veterans for Equal condemned a host of sins, one of which is said, referring to the May 22 bombing in Cavanaugh • Christiana Lilly • Denise Royal • Sean McShee • Alex Adams • Gary Kramer • Rights to boycott the event. -

Can't Get Enough of Alexander Hamilton

Can't get enough of Alexander Hamilton . Hamilton: an American Alexander Hamilton musical by Ron Chernow "Hamilton”, the hit show which moved to The personal life of Alexander Hamilton, Broadway following it’s sold-out run at an illegitimate, largely self-taught orphan The Public Theater in NYC, is the from the Caribbean who rose to become acclaimed musical about the scrappy George Washington's aide-de-camp and young immigrant Alexander Hamilton, the $10 bill the first Treasury Secretary of the United Founding Father who forever changed America with his State. revolutionary ideas and actions. During his life cut too short, he served as George Washington's chief aide, was Alexander Hamilton : the first Treasury Secretary of the United States of the making of America America, a loving husband and father, despised by his by Teri Kanefield fellow Founding Fathers, and shot to death by Aaron Burr Chronicles the life of the Founding in a legendary duel. Father, from his impoverished childhood in the West Indies and journey to New Hamilton Mixtape York City to his role in developing the Lin-Manuel Miranda promised over a year Constitution and death in a duel with ago that after he wrapped up the Aaron Burr. Hamilton cast album, he would finally start working on The Hamilton Mixtape, Alexander Hamilton : an album of remixes, covers, and the outsider “inspired bys” based on the hit Broadway by Jean Fritz musical and cultural phenomenon, Hamilton. He’s made An accessible profile of the founding good on that promise, announcing that pre-orders for the father and first U.S. -

Joseph, Decentered Vision of Diaspora Space Those Who Are Often Misrepresented Or Excluded by Socio-Political Discourse in the US

The Decentered Vision of Diaspora Space: Theological Ethnography, Migration, and the Pilgrim Church Jaisy A. Joseph Seattle University Abstract In this article, I examine the decentered vision of diaspora space that emerges from the encounters with difference present in theological ethnography, the migrant experience, and the pilgrim Church. I first argue for how crossing borders, both cultural and disciplinary, places a researcher in the intersectional power matrix of diaspora space. Second, I explore how this displacement contributes to a distinct pluralistic epistemology that invites a researcher to gain a methodological glimpse of what migrants experience existentially. Finally, I explore how the vulnerability of this decentered epistemology reveals that the Christian church is also a diaspora space, especially through a rediscovery of its own identity as a pilgrim people of “The Way.” By learning from the methodological insights of theological ethnography and the existential condition of migrants, the church too can become conscious of its own decentered position in the “already, but not yet.” “…you can be an immigrant without risking your lives Or crossing these borders with thrifty supplies All you got to do is see the world with new eyes…”1 eaturing rappers K’naan (Somali-Canadian), Snow Tha Product (Mexican-American), Riz MC (British-Pakistani), and Residente (Puerto Rican), these lyrics from The Hamilton Mixtape are inspired by the Broadway musical’s show-stopping line, “Immigrants, we get the job done!” Released Fin December 2016 amid contentious national debates on border walls and travel bans, this song speaks for Practical Matters Journal, Spring 2018, Issue 11, pp. X-XXX.