Red Goes Green

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency Appeal Final Report Syria: Floods

Emergency Appeal Final Report Syria: Floods Emergency Appeal Operation n° MDRSY004 Date of issue: 08 April 2020 GLIDE n° FL-2019-000031-SYR Date of disaster: 31 March - 30 April 2019 Operation start date:12 April 2019 Operation end date:15 October 2019 Host National Society presence: Syrian Arab Red Operation budget: CHF 3,500,000 Crescent (SARC) Headquarters; Al-Hassakeh Branch (75 staff and 120 volunteers covering Al- DREF amount allocated: CHF 500,000 (12 April 2019) Hassakeh Governorate) Number of people affected: 235,000 Number of people assisted: Planned 45,000; actual 153,417 Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners involved in the operation: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC); International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), British Red Cross, Canadian Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, Finnish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross and Swiss Red Cross. Other partner organizations involved in the operation: National government authorities, Al-Hassakeh Governorate and local authorities, and World Food Programme (WFP). The IFRC, on behalf of SARC, would like to thank the following for their generous contributions to this Appeal: Canadian Red Cross (from Canadian Government), Red Cross Society of China Hong Kong Branch, Finnish Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross (from Netherlands Government) and Swedish Red Cross. In addition, SARC would like to thank the following for their bilateral contributions: British Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, German Red Cross and Swiss Red Cross. Summary This Emergency Appeal was launched on 15 April 2019, seeking CHF 3.5 million to enable IFRC to support Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) to provide assistance to 45,000 people affected by floods in Al-Hassakeh Governorate in northeast Syria, over a six-month period, mid-April to mid-October 2019. -

Maternal, Newborn and Child Health In

MATERNAL, NEWBORN AND CHILD HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS A REPORT ON THE COMMITMENTS TO Women’s And children’s heALTH This work was co-authored by The Canadian Red Cross Society with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. The Canadian Red Cross reserves its right, title and interest in and to this work and any rights not expressly granted are reserved by the Canadian Red Cross. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this publication may be cited, copied, translated into other languages or adapted to meet local needs without prior permission from the Canadian Red Cross provided that the source is clearly stated. In consideration of this, such use shall be at the sole discretion and liability of the user and the said user shall be solely responsible, and shall indemnify the Canadian Red Cross, for any damage or loss resulting from such use. ISBN 978-1-55104-595-5 (c) International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies & Canadian Red Cross Society, Geneva, 2013 Requests for commercial reproduction should be directed to the IFRC at [email protected] and the Canadian Red Cross Society located at 170 Metcalfe St., Ottawa, ON, K2P 2P2, Canada, Tel: (613) 740-1900 or by email at [email protected]. Cover photo: Sonia Komenda/CRC ACKnowledGements The IFRC Americas Zone Health Team would like to thank the Canadian Red Cross for funding the MNCH Research Delegate position in the Americas Zone Office to conduct this project and for the extensive efforts of the Americas Team in the overall production of the report. -

Addresses of National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

ADDRESSES OF NATIONAL RED CROSS AND RED CRESCENT SOCIETIES AFGHANISTAN — Afghan Red Crescent Society, Puli COLOMBIA — Colombian Red Cross Society, Hartan, Kabul. Avenida 68, No. 66-31, Apartado Aereo 11-10, ALBANIA — Albanian Red Cross, Rue Qamil Bogotd D.E. Guranjaku No. 2, Tirana. CONGO — Congolese Red Cross, place de la Paix, ALGERIA (People's Democratic Republic of) — B.P. 4145, Brazzaville. Algerian Red Crescent, 15 bis, boulevard COSTA RICA — Costa Rica Red Cross, Calle 14, Mohamed W.Algiers. Avenida 8, Apartado 1025, San Jost. ANGOLA — Angola Red Cross, Av. Hoji Ya COTE D'lVOKE — Red Cross Society of Cote Henda 107,2. andar, Luanda. dlvoire, B.P. 1244, Abidjan. ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA — The Antigua and CUBA — Cuban Red Cross, Calle Prado 206, Coldn y Barbuda Red Cross Society, P.O. Box 727, St. Johns. Trocadero, Habana 1. ARGENTINA — The Argentine Red Cross, H. DENMARK — Danish Red Cross, 27 Blegdamsvej, Yrigoyen 2068, 7089 Buenos Aires. Postboks 2600,2100 Ktbenhavn 0. AUSTRALIA — Australian Red Cross Society, 206, DJIBOUTI — Red Crescent Society of Djibouti, Clarendon Street, East Melbourne 3002. B.P. 8, Djibouti. AUSTRIA — Austrian Red Cross, Wiedner Hauptstrasse 32, Postfach 39,1041, Vienna 4. DOMINICA — Dominica Red Cross Society, P.O. Box 59, Roseau. BAHAMAS — The Bahamas Red Cross Society, P.O. BoxN-8331,/Vajjau. DOMINICAN REPUBLIC — Dominican Red Cross, Apartado postal 1293, Santo Domingo. BAHRAIN — Bahrain Red Crescent Society, P.O. Box 882, Manama. ECUADOR — Ecuadorean Red Cross, Av. Colombia y Elizalde Esq., Quito. BANGLADESH — Bangladesh Red Crescent Society, 684-686, Bara Magh Bazar, G.P.O. Box No. 579, EGYPT — Egyptian Red Crescent Society, 29, El Galaa Dhaka. -

Dissemination of the Geneva Conventions: Australia – Austria

IN THE RED CROSS WORLD DISSEMINATION OF THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS AUSTRALIA To mark International Book Year, in 1972, the Australian Red Cross approached the authorities of the Commonwealth for financial assistance towards placing in each secondary school library a copy of three books on the work of the Red Cross and on international humanitarian law. It should be mentioned, incidentally, that the Commonwealth Government has pledged itself to give the widest possible publicity to the Geneva Conventions. The National Society has now received the funds it requested and has ordered from the ICRC 2,300 copies of the following publications: " The Principles of International Humanitarian Law ", by J. Pictet; a handbook published by the ICRC for the purpose of making the Conventions better known, and a booklet prepared by the Henry Dunant Institute giving an outline summary of the work of the Red Cross since its foundation. AUSTRIA The Junior Red Cross of Austria held a seminar on international humanitarian law on 1 and 2 December 1972. The seminar was conducted by Mr. Fritz Wendl, legal adviser of the Austrian Red Cross, with the co-operation of Mr. F. de Mulinen, ICRC head of division. The following subjects were dealt with in succession: inter- national humanitarian law in general, history of the Geneva Con- 36 IN THE RED CROSS WORLD ventions, organization of the Red Cross and, lastly, the 1949 Geneva Conventions. This was the initial stage in a campaign for the dissemination of the Conventions among youth at school, in the context of history teaching. The directorate of the Junior Red Cross assembled, in Vienna, representatives of teachers of history from all Austrian provinces. -

Emergency Appeal Final Report Europe Migration: Coordination, Response and Preparedness

Emergency Appeal Final Report Europe Migration: Coordination, Response and Preparedness Emergency Appeal n° MDR65001 Glide n° OT-2015-000069 Final Report Date of issue: 30 June 2017 Operational Timeframe: 20 November 2015 – 31 March 2017 Operational Budget: CHF 4,655,612 Appeal coverage: 74% Number of people assisted: approximately one million people supported indirectly through National Societies Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: The National Societies of Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxemburg, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and IFRC and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Governments of the affected countries, UNHCR, UNICEF, IOM and many international and local NGOs operational in the affected countries The IFRC would like to thank all those partners which have made financial contributions to this Emergency Appeal: American Red Cross, Andorran Red Cross, Australian Red Cross, British Red Cross and British Government, Canadian Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, Finnish Red Cross, Hungarian Government, Irish Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross, Luxemburg Red Cross, Monaco Red Cross, Montenegro Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross and Norwegian Government, Spanish Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross and Swiss Red Cross; and corporate partners including Apple iTunes, FedEx Services, King Digital Entertainment and Western Union Foundation. Appeal history January 2015 to March 2017: An unprecedented number of migrants arrived in Europe; it is estimated that more than 1.4 million arrived by sea and 60,000 by land during this period. -

Final Report Mid-Term Review DPRK Red Cross Cooperation Agreement Strategy (CAS) October 2018

Final Report Mid-Term Review DPRK Red Cross Cooperation Agreement Strategy (CAS) October 2018. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies 2 I Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................. 2 Review Team .................................................................................................................... 2 Glossary and abbreviations .............................................................................................. 3 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 4 2. Background and Context ........................................................................................... 5 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................. 7 4. Case Study - Integrated Programming in DPRK. ........................................................ 9 5. Key findings .............................................................................................................. 10 6. Conclusions .............................................................................................................. 15 7. Key Recommendations ............................................................................................ 16 Appendix 1. .................................................................................................................... 18 Review -

Donor Response Refreshed on 02-Oct-2021 at 08:16

Page 1 of 2 Selected Parameters Appeal Code MDRBD018 Year / Range 1900-2100 Donor response Refreshed on 02-Oct-2021 at 08:16 MDRBD018 - Bangladesh - Population Movement FUNDING REQUIREMENTS: 82,200,000 APPEAL LAUNCH DATE: 18-Mar-2017 RECEIVED TO DATE: 66,027,591 APPEAL COVERAGE TO DATE: 80% TIMEFRAME: 13-Jan-2017 to 31-Dec-2021 LOCATION: Bangladesh Bilateral Cash Inkind Goods Inkind Other Income Contributions Total contributions & Transport Personnel * CHF CHF CHF CHF CHF CHF FUNDING REQUIREMENTS 82,200,000 FUNDING Opening Balance Income American Red Cross 179,521 73,250 13,940 266,711 Australian Red Cross 826,382 361,650 1,188,032 Australian Red Cross (from Australian Government*) 1,194,930 1,194,930 Australian Red Cross (from Swedish Red Cross*) 24,644 24,644 Austrian Red Cross (from Austrian Government*) 399,617 399,617 Bahrain Red Crescent Society 88,672 88,672 Belgian Red Cross (Flanders) 51,780 51,780 Belgian Red Cross (Francophone) 51,780 51,780 British Red Cross 2,443,596 288,785 154,847 644,234 3,531,463 British Red Cross (from British Government*) 2,565,312 890 2,566,202 British Red Cross (from DEC (Disasters Emergency 269,459 269,459 Committee)*) China Red Cross, Hong Kong branch 169,712 131,521 301,232 China Red Cross, Macau Branch 250 250 Danish Red Cross 82,000 82,000 Danish Red Cross (from Danish Government*) 147,500 147,500 European Commission - DG ECHO 165,896 165,896 Finnish Red Cross 1,486,573 1,486,573 Finnish Red Cross (from Finnish Government*) 120,678 120,678 German Red Cross 23,908 23,908 IFRC at the UN Inc 977 -

Evidence of Principles in Action from Red Cross and Red Crescent National Societies Amelia B

International Review of the Red Cross (2016), 97 (897/898), 211–233. Principles guiding humanitarian action doi:10.1017/S1816383115000582 Walking the walk: Evidence of Principles in Action from Red Cross and Red Crescent National Societies Amelia B. Kyazze Amelia B. Kyazze is Senior Humanitarian Policy Adviser at the British Red Cross. She has worked for the Red Cross Movement and NGOs since 1997, when she was first deployed to Albania and Kosovo. Abstract Using evidence from nine different National Societies, this essay illustrates how the Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement are practically applied in today’s diverse contexts. The research has found that the Principles are not just abstract concepts but are in fact practical tools for initiating and implementing a range of programmes, particularly in difficult situations. The Fundamental Principles are useful for increasing access in both conflict and peaceful situations. Strong leadership is an important factor to ensure that the Principles are applied, particularly when neutrality is challenged. Lastly, all seven Principles work together and give additional strength to programmes when working as part of the Movement. Keywords: Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, Fundamental Principles, National Societies, application of the Principles, volunteers, leadership. © icrc 2015 211 A. B. Kyazze Impartiality means you have to listen and observe, without making judgements. You don’t have to give advice or try to change people. I use this a lot.1 The extremists here don’t accept humanity, the principle of humanity.2 The Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (the Movement) is made up of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and, at the time of writing, 189 National Societies. -

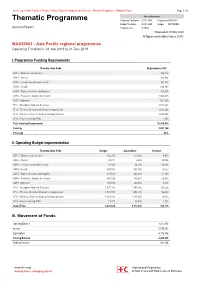

Thematic Programme - Standard Report Page 1 of 2

bo.ifrc.org > Public Folders > Finance > Donor Reports > Appeals and Projects > Thematic Programme - Standard Report Page 1 of 2 Selected Parameters Thematic Programme Reporting Timeframe 2019/1-9998 Programme MAA50001 Budget Timeframe 2019/1-9998 Budget APPROVED Annual Report Requirements APPEAL Prepared on 01 May 2020 All figures are in Swiss Francs (CHF) MAA50001 - Asia Pacific regional programmes Operating Timeframe: 01 Jan 2019 to 31 Dec 2019 I. Programme Funding Requirements Thematic Area Code Requirements CHF AOF1 - Disaster risk reduction 136,346 AOF2 - Shelter 154,964 AOF3 - Livelihoods and basic needs 167,742 AOF4 - Health 859,799 AOF5 - Water, sanitation and hygiene 413,682 AOF6 - Protection, Gender & Inclusion 1,008,425 AOF7 - Migration 561,659 SFI1 - Strenghten National Societies 3,512,663 SFI2 - Effective international disaster management 2,203,266 SFI3 - Influence others as leading strategic partners 1,395,487 SFI4 - Ensure a strong IFRC 1,598 Total Funding Requirements 10,415,630 Funding 9,003,154 Coverage 86% II. Operating Budget Implementation Thematic Area Code Budget Expenditure Variance AOF1 - Disaster risk reduction 126,358 121,936 4,422 AOF2 - Shelter 39,271 8,684 30,588 AOF3 - Livelihoods and basic needs 31,164 56,198 -25,034 AOF4 - Health 489,164 504,796 -15,632 AOF5 - Water, sanitation and hygiene 437,632 406,480 31,152 AOF6 - Protection, Gender & Inclusion 467,129 386,527 80,602 AOF7 - Migration 257,870 252,553 5,317 SFI1 - Strenghten National Societies 1,877,382 1,744,346 133,036 SFI2 - Effective international disaster management 1,550,553 1,474,120 76,432 SFI3 - Influence others as leading strategic partners 1,185,075 1,141,564 43,512 SFI4 - Ensure a strong IFRC 17,277 15,493 1,783 Grand Total 6,478,874 6,112,696 366,178 III. -

June 2019 Version 1.0

Handbook for Delegates with the Swedish Red Cross | 2019 June 2019 Version 1.0 1 Handbook for Delegates with the Swedish Red Cross | 2019 Table of contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (RCRC) ................................................ 4 1.2 Swedish Red Cross in Sweden .......................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Swedish Red Cross Internationally ................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Our areas of expertise ........................................................................................................................ 6 2. Different types of Delegate missions ............................................................................................ 7 2.1 Field Staff Delegate mission ............................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Seconded Delegate mission ............................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Surge Delegate mission ..................................................................................................................... 7 2.3.1 Emergency Response Unit (ERU) .......................................................................................... 7 2.3.2 Coordination -

Pakistan: GLIDE N° FL-2010-000141-PAK Operations Update N° 12 Monsoon Flash 23 December 2010 Floods

Emergency appeal n°MDRPK006 Pakistan: GLIDE n° FL-2010-000141-PAK Operations update n° 12 Monsoon Flash 23 December 2010 Floods Period covered by this operations update: 11 November - 10 December 2010. Appeal target (current): CHF 130,673,677 (USD 133.8 mil or EUR 97.9 mil); Appeal coverage: To date, the appeal is 60.4 per cent covered in cash and kind; and 66.8 per cent covered including contributions currently in the pipeline. Funds are still urgently needed to support the Pakistan Red Crescent Society in this operation to assist those affected by the floods. <see updated donor response report; or contact details> Appeal history: • A revised emergency appeal was launched on 15 November 2010 for CHF 130,673,677 (USD 133.8 mil or EUR 97.9 mil) to assist 130,000 families (some 900,000 people) for 24 months. • The revised emergency appeal was launched on 19 August 2010 for CHF 75,852,261 (USD 72.5 mil or EUR 56.3 mil) for 18 months to assist 130,000 flood-affected families (some 900,000 beneficiaries). • An emergency appeal was initially launched on a preliminary basis on 2 August 2010 for CHF 17,008,050 (USD 16,333,000 or EUR 12,514,600) for 9 months to assist 175,000 beneficiaries. • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF): CHF 250,000 Fatigued from months of living on humanitarian (USD 239,406 or EUR 183,589) was allocated on 30 July assistance, flood-affected families are eager to 2010 to support the National Society’s response to the resume normal lives. -

Danish Red Cross COVID-19 Preparedness Profile(As of May 5

Danish Red Cross COVID-19 preparedness profile (as of May 5, 2020) Risk & Hazards Pre-hospital care: Yes 1 INFORM COVID-19 Risk Index Health Centre(s): - Hazard & Lack coping Hospital(s): - Vulnerability Risk class Exposure capacity Higher Education: - 2.9 7.1 0.2 Low INFORM COVID-19 risk rank: 183 of 191 countries Programmes Highlighted INFORM COVID-19 sub-components Community-based Health & First Aid (CBHFA)17 Socio-Economic Vulnerability: 0.2 Is CBHFA active: Food Security: 1.4 Yes No CBHFA activities: Gender Based Violence (GBV): 0.7 - Movement (international & national): 8.8 No Health topics taught: - Behaviour (awareness & trust)): 2.7 Community Engagement & Accountability (CEA)18 Governance (effectiveness & corruption): 1.3 Access to healthcare: 1.1 HR Capacity: 3-Day Training/ToT Health context Structure: - Global Health Security Index:2 8 out of 195 No Programs: Global Health Security preparedness levels: - 14 Preventing pathogens: Most prepared Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Early detection/reporting of epidemics: Most prepared Number of volunteers trained in: Basic Psychosocial support (PSS): 1,000 Responding & mitigating spread: More prepared Psychological First Aid (PFA): 1,000 Treat the sick & protect health workers: More prepared Number of highly skilled volunteers: Social Workers (0), Psychologist (0), Psychiatrist (0), Community Healthcare Commitments (HR, funding & norms): More prepared Workers (CHWs) (0) Risk/vulnerability to biological threats: Least at risk 29 current Psychosocial (PSS) activities: Restoring