Elliott State Forest Alternatives Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost in Coos

LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Golden Falls Publishing LOST IN COOS Other books by Lionel Youst Above the Falls, 1992 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, 1997 with William R. Seaburg, Coquelle Thompson, Athabaskan Witness, 2002 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, (paper) 2002 Above the Falls, revised second edition, 2003 Sawdust in the Western Woods, 2009 Cover photo, Army C-46D aircraft crashed near Pheasant Creek, Douglas County – above the Golden and Silver Falls, Coos County, November 26, 1945. Photo furnished by Alice Allen. Colorized at South Coast Printing, Coos Bay. Full story in Chapter 4, pp 35-57. Quoted phrase in the subtitle is from the subtitle of Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, by Orville Dodge (Salem, OR: Capital Printing Co., 1898). LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thrilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River, Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Including material by Ondine Eaton, Sharren Dalke, and Simon Bolivar Cathcart Golden Falls Publishing Allegany, Oregon Golden Falls Publishing, Allegany, Oregon © 2011 by Lionel Youst 2nd impression Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9726226-3-2 (pbk) Frontier and Pioneer Life – Oregon – Coos County – Douglas County Wilderness Survival, case studies Library of Congress cataloging data HV6762 Dewey Decimal cataloging data 363 Youst, Lionel D., 1934 - Lost in Coos Includes index, maps, bibliography, & photographs To contact the publisher Printed at Portland State Bookstore’s Lionel Youst Odin Ink 12445 Hwy 241 1715 SW 5th Ave Coos Bay, OR 97420 Portland, OR 97201 www.youst.com for copies: [email protected] (503) 226-2631 ext 230 To Desmond and Everett How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. -

Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 1-1-1998 Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882" (1998). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 5. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIANS About the Author ON THE Jerry Rushford came to Malibu in April 1978 as the pulpit minister for the University OREGON TRAIL Church of Christ and as a professor of church history in Pepperdine’s Religion Division. In the fall of 1982, he assumed his current posi The Restoration Movement originated on tion as director of Church Relations for the American frontier in a period of religious Pepperdine University. He continues to teach half time at the University, focusing on church enthusiasm and ferment at the beginning of history and the ministry of preaching, as well the nineteenth century. The first leaders of the as required religion courses. movement deplored the numerous divisions in He received his education from Michigan the church and urged the unity of all Christian College, A.A. -

Elliott State Forest: Next Step Considerations for Decoupling From

ELLIOTT STATE FOREST Next Step Considerations for Decoupling from Oregon’s Common School Fund October 2018 An Oregon Consensus Assessment Report to the Oregon Department of State Lands and Oregon State Land Board 1 Assessment Team Peter Harkema, Oregon Consensus Director Brett Brownscombe, Senior Project Manager Amy Delahanty, Project Associate Acknowledgements Oregon Consensus deeply appreciates all those who generously gave their time to inform this assessment and report. About Oregon Consensus Oregon Consensus (OC) was established by state statute as the State of Oregon's program for public policy conflict resolution and collaborative governance. The program provides mediation and other collaborative services to public bodies and stakeholders who are seeking new approaches to challenging public issues. OC conducts assessments and designs and facilitates impartial and transparent collaborative processes that foster balanced participation and durable agreements. OC is housed in the National Policy Consensus Center in the Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University. Contact Oregon Consensus National Policy Consensus Center Hatfield School of Government Portland State University 506 SW Mill Street, Room 720 PO Box 751 Portland, OR 97207-0751 (503) 725-9077 [email protected] www.oregonconsensus.org 2 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1. Purpose of report .............................................................................................................................................. -

Download Chapter

Table Of Contents Conservation Toolbox............................................................................................................................... 3 Outreach, Education, and Engagement................................................................................................... 4 Voluntary Conservation Programs......................................................................................................... 16 Conservation in Urban Areas.................................................................................................................. 23 Planning and Regulatory Framework..................................................................................................... 30 General References.................................................................................................................................. 50 Conservation Toolbox Everyone has a role in the successful implementation of the Oregon Conservation Strategy. The Conservation Toolbox provides recommendations to support implementation and suggestions for additional information and assistance. Key components of the Conservation Toolbox include: Outreach, Education, and Engagement Conservation in Urban Areas Oregon’s Existing Planning and Regulatory Framework Voluntary Conservation Programs General References: additional resources outside of the references provided in each section Outreach, Education, and Engagement Connecting people to nature is an important element of successful Conservation Strategy implementation. Acquiring -

2019-21 Budget Highlights

2019-21 BUDGET HIGHLIGHTS Legislative Fiscal Office September 2019 State of Oregon Ken Rocco Legislative Fiscal Office Legislative Fiscal Officer 900 Court St. NE, Rm. H-178 Paul Siebert Salem, OR 97301 Deputy Legislative Fiscal Officer 503-986-1828 September 9, 2019 To the Members of the Eightieth Oregon Legislative Assembly: Following is the 2019-21 Budget Highlights, which provides summary information on the legislatively adopted budget; legislative actions affecting the budget; program areas and agencies; state bonding and capital construction; budget notes; information technology; fiscal impact statements; substantive bills with a budget effect; and appendices containing detailed data. We hope you find this resource useful and invite you to call the Legislative Fiscal Office if you have any questions. Ken Rocco Legislative Fiscal Officer Table of Contents Summary of the 2019-21 Legislatively Adopted Budget ............................................................. 1 Summary of Legislative Actions Affecting the Budget ............................................................... 33 Program Area Summaries .......................................................................................................... 58 State Bonding and Capital Construction .................................................................................. 117 Budget Notes ........................................................................................................................... 120 Information Technology.......................................................................................................... -

A. CALL to ORDER B. APPROVAL of MINUTES of October 8, 2013 C

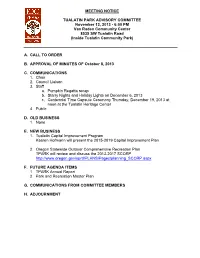

MEETING NOTICE TUALATIN PARK ADVISORY COMMITTEE November 12, 2013 - 6:00 PM Van Raden Community Center 8535 SW Tualatin Road (Inside Tualatin Community Park) A. CALL TO ORDER B. APPROVAL OF MINUTES OF October 8, 2013 C. COMMUNICATIONS 1. Chair 2. Council Liaison 3. Staff a. Pumpkin Regatta recap b. Starry Nights and Holiday Lights on December 6, 2013 c. Centennial Time Capsule Ceremony Thursday, December 19, 2013 at noon at the Tualatin Heritage Center 4. Public D. OLD BUSINESS 1. None E. NEW BUSINESS 1. Tualatin Capital Improvement Program Kaaren Hofmann will present the 2015-2019 Capital Improvement Plan 2. Oregon Statewide Outdoor Comprehensive Recreation Plan TPARK will review and discuss the 2013-2017 SCORP http://www.oregon.gov/oprd/PLANS/Pages/planning_SCORP.aspx F. FUTURE AGENDA ITEMS 1. TPARK Annual Report 2. Park and Recreation Master Plan G. COMMUNICATIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS H. ADJOURNMENT City of Tualatin DRAFT TUALATIN PARK ADVISORY COMMITTEE MINUTES October 8, 2013 MEMBERS PRESENT: Dennis Wells, Valerie Pratt, Kay Dix, Stephen Ricker, Connie Ledbetter MEMBERS ABSENT: Bruce Andrus-Hughes, Dana Paulino, STAFF PRESENT: Carl Switzer, Parks and Recreation Manager PUBLIC PRESENT: None OTHER: None A. CALL TO ORDER Meeting called to order at 6:06. B. APPROVAL OF MINUTES The August 13, 2013 minutes were unanimously approved. C. COMMUNICATIONS 1. Public – None 2. Chairperson – None 3. Staff – Staff presented an update to the 10th Annual West Coast Giant Pumpkin Regatta. Stephen said he would like to race again. TPARK was invited to attend the special advisory committee meeting about Seneca Street extension. TPARK was informed that the CDBG grant application for a new fire sprinkler system for the Juanita Pohl Center was submitted. -

March/April 2019

Still time to register for Spring AUDUBON SOCIETY of PORTLAND Break and Summer Camps! Page 7 MARCH/APRIL 2019 Black-throated Volume 83 Numbers 3&4 Warbler Gray Warbler Time for Modern Nesting Birds and Spring Optics Board Elections and Flood Management Native Plants Fair Articles of Incorporation Page 4 Page 5 Page 9 Page 10 From the Executive Director: BIRDATHON A Historic Gift to 2019 Counting Birds Expand Our Sanctuary Because Birds Count! Needs Your Support Registration begins March 15 by Nick Hardigg oin the biggest Birdathon ur 150-acre Portland wildlife sanctuary is the this side of the Mississippi— cumulative result of 90 years of private and public you’ll explore our region’s conservation campaigns, each one adding to the J O birding hotspots during strength and integrity of wild lands protected previously. A Sanctuaries Manager Esther Forbyn celebrates the latest addition. migration, learn from expert beautiful network of more than four miles of nature trails, now and raise funds later—protecting valuable natural land birders, AND help raise money meandering through young and old-growth forests, creeks, that connects with Forest Park—or eventually see 30 town- to protect birds and habitat and sword ferns, our Sanctuary’s founding dates back houses rise in the quietest reaches of our Sanctuary. Our across Oregon! Last year, you to the 1920s when our board envisioned protecting and costs would be $500,000 to pay off the owner’s mortgage, helped us raise over $195,000 and we hope you’ll join restoring a Portland sanctuary for birds and other wildlife. -

Recent History of Oregon's Property Tax System

RECENT HISTORY OF OREGON’S PROPERTY TAX SYSTEM WITH AN EMPHASIS ON ITS IMPACT ON MULTNOMAH COUN TY LOCAL GOVERNMENTS RECENT HISTORY OF OREGON’S PROPERTY TAX SYSTEM WITH AN EMPHASIS ON ITS IMPACT ON MULTNOMAH COUNTY LOCAL GOVERNMENTS TOM LINHARES Edited by Elizabeth Provost December 2011 Author, Editor, Acknowledgements and Dedication About the Author : Tom Linhares has been the Executive Director of the Multnomah County Tax Supervising & Conservation Commission since April 2004. The Commission, or TSCC as it is commonly called, is made up of five county residents who are appointed by the Governor to four-year terms. The Commission oversees the budget process and property tax levy for all taxing districts that are principally located in Multnomah County, currently numbering 39. In addition, the Commission is required to hold public hearings before any district can place a property tax measure on the ballot. Prior to coming to the Commission, Tom was the elected County Assessor for Columbia County, serving in that position for 17 years. During that time he served as the president of the Oregon State Association of County Assessors (1998-99) and throughout the 1997 Legislative Session he was the Association’s Legislative Committee Chair, where he helped craft legislation to implement Ballot Measure 50. Tom is a graduate of Portland State University with a degree in Political Science. He and his wife, Val, live in Columbia City. They have one daughter, Julie, who is principal of Marshall High School in Bend. About the Editor : Elizabeth (Libby) Provost is an independent historian and researcher specializing in historic preservation consulting and oral history. -

Final Elliott State Forest 2011 Management Plan

Elliott State Forest Management Plan Oregon Department of State Lands Oregon Department of Forestry FINAL PLAN November 2011 Acronyms and Abbreviations AOP Annual Operations Plan APHIS USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service BLM Bureau of Land Management BMP best management practices BOF Board of Forestry BOFL Board of Forestry Land CEQ Council on Environmental Quality cfs cubic feet per second CI confidence interval CSF Common School Fund CSFL Common School Forest Lands CWA Clean Water Act DBH diameter breast height DEQ Oregon Department of Environmental Quality DOGAMI Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries DSL Oregon Department of State Lands EPA Environmental Protection Agency ESA Endangered Species Act ESU evolutionarily significant unit FC federal candidate species FE federal endangered species FMP Forest Management Plan FPA Forest Practices Act FT federal threatened species GIS geographic information system GTR General Technical Report HCP Habitat Conservation Plan HUC hydrologic unit code IP Implementation Plan IPM integrated pest management ITP Incidental Take Permit LCDC Land Conservation and Development Commission November 2011 Elliott State Forest Management Plan iii LMCS Land Management Classification System LW large wood MBF thousand board feet mg/L milligrams per liter MMBF million board feet MMMA Marbled Murrelet Management Area NAAQS National Ambient Air Quality Standards NEPA National Environmental Policy Act NOAA Fisheries National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries (formerly National -

Does Oregon's Constitution Need a Due Process Clause?" Thoughts on Due Process and Other Limigations on State Action Thomas A

Washington Law Review Online Volume 91 Article 8 2016 "Does Oregon's Constitution Need a Due Process Clause?" Thoughts on Due Process and Other Limigations on State Action Thomas A. Balmer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlro Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Balmer, Thomas A. (2016) ""Does Oregon's Constitution Need a Due Process Clause?" Thoughts on Due Process and Other Limigations on State Action," Washington Law Review Online: Vol. 91 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlro/vol91/iss1/8 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Law Review Online by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Balmer_Copy Edit Complete.docx (Do Not Delete) 5/30/2016 11:40 AM “DOES OREGON’S CONSTITUTION NEED A DUE PROCESS CLAUSE?” THOUGHTS ON DUE PROCESS AND OTHER LIMITATIONS ON STATE ACTION Thomas A. Balmer* INTRODUCTION During a legislative hearing last year, an Oregon state senator asked, “Does Oregon’s Constitution need a due process clause?” That question raises fundamental issues of constitutional law and of the relationship between the federal and state constitutions. Can and should state courts rely primarily on federal constitutional principles, made applicable to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, in deciding critical -

CITY COUNCIL Agenda

CITY COUNCIL Agenda 520 E. Cascade Avenue - PO Box 39 - Sisters, Or 97759 | ph.: (541) 549-6022 | www.ci.sisters.or.us Wednesday, July 14, 2021 520 E. Cascade Avenue, Sisters, OR 97759 5:30 P.M. WORKSHOP 1. Review Bryant, Lovlien & Jarvis Professional Services Agreement-Misley 2. Charter Review Discussion-Misley 3. Discuss Proposed Changes to Municipal Code & Development Code Relating to Public Trees-Bertagna, Mardell 4. Discussion of Habitat for Humanity Affordable Housing Grant Application-Misley 5. Other Business-Staff/Council 6:30 P.M. CITY COUNCIL REGULAR MEETING I CALL TO ORDER/PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE II ROLL CALL III APPROVAL OF AGENDA IV VISITOR COMMUNICATION V CONSENT AGENDA All matters listed within the Consent Agenda have been distributed to each member of the Sisters City Council for reading and study, are routine and will be enacted by one motion of the Council with no separate discussions. If separate discussion is desired, that item may be removed from the Consent Agenda and placed on the Regular Agenda by request. A. Minutes 1. June 09, 2021-Regular 2. June 09, 2021-Workshop B. Bills to Approve. 1. July 09, 2021- Accounts Payable C. Approve Transit Services Agreement #33559 between the Oregon Department of Transportation and the City of Sisters for Public Transportation Services and Authorize the City Manager to Execute the Agreement. This agenda is also available via the Internet at www.ci.sisters.or.us July 14, 2021 Page 2 D. Approve an Agreement for Oregon Enterprise Zone Extended Abatement for Nosler, Inc. E. Approve an Agreement for On-Call Electrical Services with Smith Rock Electric, LLC and Authorize the City Manager to Execute the Agreement. -

Northwest Oregon State Forests Management Plan

Northwest Oregon State Forests Management Plan Revised Plan April 2010 Oregon Department of Forestry Northwest Oregon State Forests Management Plan January 2001 Plan Structure Classes and Habitat Conservation Plan references revised April 2010 Oregon Department of Forestry FINAL PLAN “STEWARDSHIP IN FORESTRY” List of Acronyms and Abbreviations Used ATV All-terrain vehicle NMFS National Marine Fisheries Service BAT Best Available Technology NWOA Northwest Oregon Area BLM Bureau of Land Management OAR Oregon Administrative Rules BMP Best Management Practices ODA Oregon Dept. of Agriculture BOFL Board of Forestry Lands ODF Oregon Dept. of Forestry BPA Bonneville Power Administration ODFW Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife CEQ Council on Environmental Quality OFS Older forest structure (forest stand CMAI Culmination of Mean Annual type) Increment OHV Off-highway vehicles CMZ Channel migration zone ONHP Oregon Natural Heritage Program CRS Cultural, Recreation, and Scenic ORS Oregon Revised Statutes Inventory System OSCUR State forest inventory system CSC Closed single canopy (forest stand PM Particulate matter type) PSD Prevention of Significant CSFL Common School Forest Lands Deterioration CSRI Coastal Salmon Restoration REG Regeneration (forest stand type) Initiative RMA Riparian management area CWA Clean Water Act ROS Recreation Opportunity Spectrum DBH Diameter breast height RV Recreational vehicle DEQ Oregon Department of SBM Structure-based management Environmental Quality SCORP Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor DFC Desired future condition