Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chipko Movement: a People’S History

Book Review – The Chipko Movement: A People’s History Yogesh Upadhyay Vol. 8, pp. 46–52 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk 2021 | The South Asianist 8: 46-52 | 46 Vol. 8, pp. 41-45 Book Review The Chipko Movement: A People’s History By Shekhar Pathak , translated by Manisha Chaudhry. Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2020. 371 pages; ISBN: 978-8-178-24555-3 YOGESH UPADHYAY “If trees remain, the mountains remain, and so does the country”1 The Forest Rights Act, 2006, recognised the historical injustice done to forest dwellers in both colonial and independent India in not acknowledging their centrality to the very survival of the forest ecosystem and promised to invest them with forest rights. Promising as the law seemed, my year-long engagement with the Himalayan forest dwellers in 2019 revealed that the recognised injustice continues unabated. Using the case study of the Chipko Movement, this book (The Chipko Movement: A People’s History) attempts to enliven the politics around forest management and suggests historical reasons for the continuing problem and its solution. Given ongoing corporatisation, centralisation and dilution of environmental laws on the one side, and burgeoning ecological disasters on the other, this book can be read as an attempt to bring home the point that the permanent and immanent solution to our ecological and economic crisis lies in giving forest 1 Pathak, S. The Chipko Movement: A People’s History (Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2020), 157 2021 | The South Asianist 8: 46-52 | 47 rights to forest dwellers, who know the forest more deeply and are more farsighted in managing it than any other agent. -

Uttarakhand Van Panchayats

Law Environment and Development JournalLEAD ADMINISTRATIVE AND POLICY BOTTLENECKS IN EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT OF VAN PANCHAYATS IN UTTARAKHAND, INDIA B.S. Negi, D.S. Chauhan and N.P. Todaria COMMENT VOLUME 8/1 LEAD Journal (Law, Environment and Development Journal) is a peer-reviewed academic publication based in New Delhi and London and jointly managed by the School of Law, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) - University of London and the International Environmental Law Research Centre (IELRC). LEAD is published at www.lead-journal.org ISSN 1746-5893 The Managing Editor, LEAD Journal, c/o International Environmental Law Research Centre (IELRC), International Environment House II, 1F, 7 Chemin de Balexert, 1219 Châtelaine-Geneva, Switzerland, Tel/fax: + 41 (0)22 79 72 623, [email protected] COMMENT ADMINISTRATIVE AND POLICY BOTTLENECKS IN EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT OF VAN PANCHAYATS IN UTTARAKHAND, INDIA B.S. Negi, D.S. Chauhan and N.P. Todaria This document can be cited as B.S. Negi, D.S. Chauhan and N.P. Todaria, ‘Administrative and Policy Bottlenecks in Effective Management of Van Panchayats in Uttarakhand, India’, 8/1 Law, Environment and Development Journal (2012), p. 141, available at http://www.lead-journal.org/content/12141.pdf B.S. Negi, Deputy Commissioner, Ministry of Agriculture, Govt. of India, Krishi Bhawan, New Delhi, India D.S. Chauhan, Department of Forestry, P.O. -59, HNB Garhwal University, Srinagar (Garhwal) – 246 174, Uttarakhand, India N.P. Todaria, Department of Forestry, P.O. -59, HNB Garhwal University, Srinagar (Garhwal) – 246 174, Uttarakhand, India, Email: [email protected] Published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 License TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

A Political Ecology of the Chipko Movement

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2006 A POLITICAL ECOLOGY OF THE CHIPKO MOVEMENT Sya Kedzior University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kedzior, Sya, "A POLITICAL ECOLOGY OF THE CHIPKO MOVEMENT" (2006). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 289. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/289 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS A POLITICAL ECOLOGY OF THE CHIPKO MOVEMENT The Indian Chipko movement is analyzed as a case study employing a geographically-informed political ecology approach. Political ecology as a framework for the study of environmental movements provides insight into the complex issues surrounding the structure of Indian society, with particular attention to its ecological and political dimensions. This framework, with its focus on social structure and ecology, is distinct from the more “traditional” approaches to the study of social movements, which tend to essentialize their purpose and membership, often by focusing on a single dimension of the movement and its context. Using Chipko as a case-study, the author demonstrates how a geographical approach to political ecology avoids some of this essentialization by encouraging a holistic analysis of environmental movements that is characterized by a “bottom-up” analysis, grounded at the local level, which also considers the wider context of the movement’s growth by synthesizing socio-political and ecological analyses. -

Third State Finance Commission

CHAPTER 5 STATUS OF DECENTRALISED GOVERNANCE A. Brief Historical Overview 5.1 Modern local government in India has a rather long history extending to the earliest years of British rule under the East India Company, when a municipal body was established in Madras in 1688 followed soon thereafter by Bombay and Calcutta. These earliest corporations neither had any legislative backing, having been set up on the instructions of the Directors of the East India Company with the consent of the Crown, nor were they representative bodies as they consisted entirely of nominated members from among the non-native population. They were set up mainly to provide sanitation in the Presidency towns, but they did not prove to be very effective in this task. Act X of 1842 was the first formal measure for the establishment of municipal bodies. Though applicable only to the Bengal Presidency it remained inoperative there. Town Committees under it were, however, set up in the two hill stations of Mussoorie and Nainital in 1842 and 1845 respectively, on the request of European residents. Uttarakhand thus has the distinction of having some of the earliest municipalities established in the country, outside the Presidency towns. Their record too was not very encouraging. When the Government of India passed Act XXVI in 1850 the municipal bodies of Mussoorie and Nainital were reconstituted under it. 5.2 The motivation for establishing municipal bodies in the initial years was not any commitment to local government on the part of the British. Rather it was inspired by the desire to raise money from the local population for provision of civic services. -

State Disaster Management Action Plan for the State of Uttarakhand

State Disaster Management Action Plan for the State of Uttarakhand Disaster Mitigation & Management Centre Uttarakhand Secretariat Rajpur Road, Dehradun-248001 1 INDE( C)APTER- I Introduction Page No. 1. Introduction 01 1.1 State Profile ,Social, Economic and Demographic 03 1.2 Demographic & Socio-economic Profile 03 1.3 Area & Administrative Divisions 04 1.4 Geology* 0. 1.5 Climate 06 1.6 Temperature 06 1.8 Literacy and Education 06 1.9 Health Infrastructure of Uttarakhand 08 1.10 Forests 10 1.11 Agriculture 10 1.12 Food Grain Production 11 1.13 Land Use Pattern 1 1.14 Industrial profile of Uttarakhand 1 1.15 Transport & Communication 14 1.16 Power & Electrical Installations 16 C)APTER- II 0ulnera1ility Analysis & Risk Analysis 2.1 Vulnerability Analysis 18 2.2 State Vulnerabilities 13 2.2.1 Vulnerabilities to Earthquakes 0 2.2.2 Earthquake Hazard Map 1- 2.3 Vulnerability to Landslides 3 2.3.1 Landslides Hazard Zonation Mapping 4 2.4 Vulnerability to Floods . 2.5.1 Cloudbursts 8 2.5.2 Flash Floods 8 2.6 Avalanches 3 2.7 Drought 3 2.8 Hailstorms 3 2 2.9 Socio-Economic Vulnerabilities 30 2.10 Economy & Lack of access to infrastructure 31 2.11 Education 3 2.12 High Mortality 3 2.13 Housing 3 2.14 Gender discrimination 34 2.15 People needing special care 34 2.16 Live Stocks 34 C)APTER- III Preventive Measures 3.1 Early Warning and Dissemination systems 36 3.2 State Emergency Operation Centre 37 3.2.1 Communication Network 37 3.2.2 Police Wireless Set 38 3.2.3 Alert and Information System (SMS Software) 38 3.3 Early warning System:- 40 3.3.1 Rainfall Report 40 Prevention 3.4 Prevention 41 Mitigation Strategy 3.5 Mitigation Strategy 4 3.5.1 Structural Mitigation 4 3.5.1.1 Risk Assessment & Vulnerability Analysis 43 3.5.1.2 Hazard Assessment 44 3.5.1.3 Building Bye-laws & Codes 4. -

Tariff Orders for FY 2018-19

Order on True up for FY 2016-17, Annual Performance Review for FY 2017-18 & ARR for FY 2018-19 For Power Transmission Corporation of Uttarakhand Ltd. March 21, 2018 Uttarakhand Electricity Regulatory Commission Vidyut Niyamak Bhawan, Near I.S.B.T., P.O. Majra Dehradun – 248171 Table of Contents 1 Background and Procedural History .................................................................................................... 4 2 Stakeholders’ Objections/Suggestions, Petitioner’s Responses and Commission’s Views ...... 8 2.1 Capitalisation of New Assets ...................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1 Stakeholder’s Comments ........................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.2 Petitioner’s Response ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1.3 Commission’s Views .................................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Carrying Cost of Deficit ............................................................................................................................. 10 2.2.1 Stakeholder’s Comments ......................................................................................................................... 10 2.2.2 Petitioner’s Response .............................................................................................................................. -

Hydrological Impact of Deforestation in the Central Himalaya

Hydrology ofMountainous^4reoi (Proceedings of the Strbské Pleso Workshop, Czechoslovakia, June 1988). IAHS Publ. no. 190, 1990. Hydrological impact of deforestation in the central Himalaya M. J. HAIGH Geography Unit, Oxford Polytechnic Headington, Oxford, England J. S. RAWAT, H. S. BISHT Department of Geography, Kumaun University Almora, U.P., India ABSTRACT Deforestation is the most serious environmental problem in Uttarakhand, home of the Chipko Movement, the Third World's leading nongovernmental organization (NGO) dedicated to forest con servation. This group exists because of the rural people's concern for the loss of forests and their personal experience of the envi ronmental consequences. Despite this, it has become fashionable for scientists from some international organizations to argue there is little evidence for recent deforestation, desertification, acce lerated erosion and increased flooding in the region. This paper tries to set the record straight. It summarizes results collected by field scientists in Uttarakhand. These data reinforce the popu lar view that deforestation and environmental decline are very ser ious problems. Preliminary results from the Kumaun University/Ox ford Polytechnic instrumented catchment study are appended. This catchment is set in dense Chir (Pinus roxburghii) forest on a steep slope over mica schist in a protected wildlife sanctuary on the ur ban fringe at Almora, U.P. The results demonstrate a pattern of sediment flushing associated with the rising flows of the Monsoon. INTRODUCTION Deforestation is the most serious environmental problem in Uttar akhand, the Himalaya of Uttar Pradesh, India (Fig. 1). This tract, which covers nearly 52 thousand km2 on the western borders of Nepal, is home of the "Chipko" Movement, the Third World's leading NGO devoted to forest conservation (Haigh, 1988a). -

The Chipko Movement: a Pragmatic, Material & Spiritual Reinterpretation

DEPARTMENT OF SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY Internet Publication Series on South Asian History Editors: Gita Dharampal-Frick (General Editor) Rafael Klöber (Associate Editor) Manju Ludwig (Associate Editor) ______________________________________________________ Publication No. 7 The Chipko Movement: A Pragmatic, Material & Spiritual Reinterpretation by Julio I. Rodriguez Stimson ©Julio I. Rodriguez Stimson The Chipko Movement: A Pragmatic, Material & Spiritual Reinterpretation Julio I. Rodríguez Stimson Seminar: Environmental Sustainability in South Asia: Historical Perspectives, Recent Debates and Dilemmas Professors: Divya Narayanan & Gita Dharampal-Frick Semester: WiSe 2015/16 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 Long-Term Causes ............................................................................................................ 2 The Chipko Movement ...................................................................................................... 4 The Ideology of Chipko .................................................................................................... 5 Consequences .................................................................................................................... 6 Ecologically Noble Savages, Environmentality and Pragmatism ..................................... 8 Deep Ecology and Spirituality ......................................................................................... -

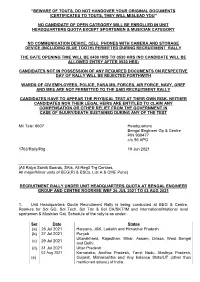

Beware of Touts, Do Not Handover Your Original Documents /Certificates to Touts, They Will Mislead You”

“BEWARE OF TOUTS, DO NOT HANDOVER YOUR ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS /CERTIFICATES TO TOUTS, THEY WILL MISLEAD YOU” NO CANDIDATE OF OPEN CATEGORY WILL BE ENROLLED IN UNIT HEADQUARTERS QUOTA EXCEPT SPORTSMEN & MUSICIAN CATEGORY NO COMMUNICATION DEVICE, CELL PHONES WITH CAMERA AND STORAGE DEVICE (INCLUDING BLUE TOOTH) PERMITTED DURING RECRUITMENT RALLY THE GATE OPENING TIME WILL BE 0430 HRS TO 0530 HRS (NO CANDIDATE WILL BE ALLOWED ENTRY AFTER 0530 HRS) CANDIDATES NOT IN POSSESSION OF ANY REQUIRED DOCUMENTS ON RESPECTIVE DAY OF RALLY WILL BE REJECTED FORTHWITH WARDS OF CIV EMPLOYEES, POLICE, PARA MIL FORCES, AIR FORCE, NAVY, GREF AND MES ARE NOT PERMITTED TO THE SAID RECRUITMENT RALLY CANDIDATES HAVE TO APPEAR THE PHYSICAL TEST AT THEIR OWN RISK. NEITHER CANDIDATES NOR THEIR LEGAL HEIRS ARE ENTITLED TO CLAIM ANY COMPENSATION OR OTHER RELIEF FROM THE GOVERNMENT IN CASE OF INJURY/DEATH SUSTAINED DURING ANY OF THE TEST Mil Tele: 6607 Headquarters Bengal Engineer Gp & Centre PIN 900477 c/o 56 APO 1763/Rally/Rtg 19 Jun 2021 _________________________________________ (All Rajya Sainik Boards, SAIs, All Regtl Trg Centres, All major/Minor units of BEG(R) & BSCs, List A & CME Pune) RECRUITMENT RALLY UNDER UNIT HEADQUARTERS QUOTA AT BENGAL ENGINEER GROUP AND CENTRE ROORKEE WEF 26 JUL 2021 TO 03 AUG 2021 1. Unit Headquarters Quota Recruitment Rally is being conducted at BEG & Centre, Roorkee for Sol GD, Sol Tech, Sol Tdn & Sol Clk/SKT/IM and International/National level sportsmen & Musician Cat. Schedule of the rally is as under:- Ser Date States (a) 26 Jul 2021 Haryana, J&K, Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh (b) 27 Jul 2021 Punjab Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Bihar, Assam, Orissa, West Bengal (c) 29 Jul 2021 and Delhi (d) 31 Jul 2021 Uttar Pradesh 02 Aug 2021 Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, (e) Gujarat, Maharashtra and Any balance State/UT (other than mentioned above) of India. -

Format of Bio-Data in Respect of Persons Desirous of Inclusionin DPE Databank

- Format of Bio-data in respect of persons desirous of inclusionin DPE databank 1. Name and surname (in full):Anirban Mukhopadhaya 2. Director Identification Number (refer Note 1) : 07197450 3. Income Tax PAN: 4. Gender : Male 4. Nationality : Indian 5. Father's name and mother's name and Spouse's name (if married) : Late S.R. Mukerji, (father),Smt. Sipra Mukerji, (mother), Debasrita Mukhopadhaya, (spouse) 6. Date of Birth: 18June 1957 7. Present Position/Occupation Superannuated from the Indian Administrative Service on 30/ 06/2017 8. Full address (present and permanent) with PIN code, Phone number, Mobile Number, E-Mail address) : - Mobile No. 9414016355 Landiine. 0141 - 4087747. 9. Educational & Professional Qualification (Graduation onwards) S.No. Course Subjects University/Institut e Year of Passing 1 BA Hons. Natural Cambridge (U.K.) 1978 Sciences 2. MA Natural Cambridge (U.K.) 1982 Sciences 3. MA History Delhi 1980 4. MBA Finance Southern Cross 1996 Specialisation (Australia) 10 . Work Experience (Recent & Highlights) - Full Service History Sheet attached S.No. Organization/ Post Held Period (From To) Nature of Institute Work/ Area of Specialization 1 Rajasthan Chairman 06/05/2017 -30/06/2017 Judicial, Civil Services (superannuation) (Personnel) Appellate Tribunal, Jaipur 2 Rajasthan Chairman & 01/07/2016 - Urban Housing Housing 05/05/2017 Development & Board Commissioner Housing and Corporate Governance as Director in the Jaipur Metro Rail Corporation 3 Government Additional 20/09/2014 - Security, of Rajasthan Chief 01/07/2016 Administration, Secretary, Law, Finance & Home, Civil Corporate Defence,Home Governance as Guards, Jails, Director in the State Bureau Police Housing of Corporation Investigation and ex-officio Chief Vigilance Commissioner Rajas than 4 Government Principal 16/08/2010 - Personnel, of Rajasthan Secretary & 07/08/2014 Legal & later Constitutional, Additional University Chief administration, Secretary to Tribal the Governor Development of Rajasthan etc. -

Participant List

15th Round of MCTP Phase IV, 2021 (02-08-2021 to 27-08-2021) List of Participants Sl. No.Name & Address Gender Cadre Allotment Year 1 Dr. Sharat Chauhan, Male AGMUT 1994 Principal Secretary, Finance and Health, Government of Arunachal Pradesh, Block-02, 3rd Floor, Civil Secretariat, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh-791111 2 Swati Sharma, Female AGMUT 2003 Secretary, Government of NCT of Delhi, Delhi Secretariat, I P Estate, New Delhi- 110002 3 Ankur Garg, Male AGMUT 2003 Commissioner Trade and Taxes, Government of NCT of Delhi, 33-A, Shamnath Marg, New Delhi-110054 4 Shurbir Singh, Male AGMUT 2004 Secretary Finance and Chief Electoral Officer, Government of Pondicherry, Office of Secretary Finance, 3rd floor Chief Secretariat, Goubert Avenue, Pondicherry-605001 5 Garima Gupta, Female AGMUT 2004 Secretary, Government of NCT of Delhi, 6 by 8 Lancer Road, Opp. Vishwavidylaya Metro Station, Timarpur, Civil Lines, Delhi-110054 6 Niharika Rai, Female AGMUT 2005 Commissioner, Government of Arunachal Pradesh, Room No. 202, Block 2, Civil Secretariat, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh-791111 7 Ashish Madhaorao More, Male AGMUT 2005 Additional Commissioner, North Delhi Municipal Corporation, Government of NCT of Delhi, Flat No. A-8, Delhi Government Residential Complex, Sector D-2, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110070 8 H. Lalengmawia, Male AGMUT 2005 Commissioner and Secretary, Power And Electricity Department And Sports, Government of Mizoram Room No. 116,117, Building No. 1, MINECO, KHATLA, Aizawl, Mizoram-796001 9 Kunal, Male AGMUT 2005 Chief Electoral Officer, Office of Chief Electoral Office, Government of Goa, Old IPHB Building, Altinho, Panaji, Goa-403001 10 Rupesh Kumar Thakur, Male AGMUT 2006 Director, Ministry of Labour, Shram Shakti Bhawan, Rafi Marg, New-Delhi-110001 11 Ashok Kumar, Male AGMUT 2006 Secretary, Government of Puducherry, No. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 CONTENTS PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES PROCEDURAL MATTERS PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha Rajya Sabha State Legislatures RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Second Session of the Seventeenth Lok Sabha II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 250th Session of the Rajya Sabha III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union and State Governments during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITES ______________________________________________________________________________ CONFERENCES AND SYMPOSIA 141st Assembly of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU): The 141st Assembly of the IPU was held in Belgrade, Serbia from 13 to 17 October, 2019. An Indian Parliamentary Delegation led by Shri Om Birla, Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha and consisting of Dr. Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Ms. Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Smt.