The Chipko Movement: a People’S History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Political Ecology of the Chipko Movement

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2006 A POLITICAL ECOLOGY OF THE CHIPKO MOVEMENT Sya Kedzior University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kedzior, Sya, "A POLITICAL ECOLOGY OF THE CHIPKO MOVEMENT" (2006). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 289. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/289 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS A POLITICAL ECOLOGY OF THE CHIPKO MOVEMENT The Indian Chipko movement is analyzed as a case study employing a geographically-informed political ecology approach. Political ecology as a framework for the study of environmental movements provides insight into the complex issues surrounding the structure of Indian society, with particular attention to its ecological and political dimensions. This framework, with its focus on social structure and ecology, is distinct from the more “traditional” approaches to the study of social movements, which tend to essentialize their purpose and membership, often by focusing on a single dimension of the movement and its context. Using Chipko as a case-study, the author demonstrates how a geographical approach to political ecology avoids some of this essentialization by encouraging a holistic analysis of environmental movements that is characterized by a “bottom-up” analysis, grounded at the local level, which also considers the wider context of the movement’s growth by synthesizing socio-political and ecological analyses. -

Hydrological Impact of Deforestation in the Central Himalaya

Hydrology ofMountainous^4reoi (Proceedings of the Strbské Pleso Workshop, Czechoslovakia, June 1988). IAHS Publ. no. 190, 1990. Hydrological impact of deforestation in the central Himalaya M. J. HAIGH Geography Unit, Oxford Polytechnic Headington, Oxford, England J. S. RAWAT, H. S. BISHT Department of Geography, Kumaun University Almora, U.P., India ABSTRACT Deforestation is the most serious environmental problem in Uttarakhand, home of the Chipko Movement, the Third World's leading nongovernmental organization (NGO) dedicated to forest con servation. This group exists because of the rural people's concern for the loss of forests and their personal experience of the envi ronmental consequences. Despite this, it has become fashionable for scientists from some international organizations to argue there is little evidence for recent deforestation, desertification, acce lerated erosion and increased flooding in the region. This paper tries to set the record straight. It summarizes results collected by field scientists in Uttarakhand. These data reinforce the popu lar view that deforestation and environmental decline are very ser ious problems. Preliminary results from the Kumaun University/Ox ford Polytechnic instrumented catchment study are appended. This catchment is set in dense Chir (Pinus roxburghii) forest on a steep slope over mica schist in a protected wildlife sanctuary on the ur ban fringe at Almora, U.P. The results demonstrate a pattern of sediment flushing associated with the rising flows of the Monsoon. INTRODUCTION Deforestation is the most serious environmental problem in Uttar akhand, the Himalaya of Uttar Pradesh, India (Fig. 1). This tract, which covers nearly 52 thousand km2 on the western borders of Nepal, is home of the "Chipko" Movement, the Third World's leading NGO devoted to forest conservation (Haigh, 1988a). -

The Chipko Movement: a Pragmatic, Material & Spiritual Reinterpretation

DEPARTMENT OF SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY Internet Publication Series on South Asian History Editors: Gita Dharampal-Frick (General Editor) Rafael Klöber (Associate Editor) Manju Ludwig (Associate Editor) ______________________________________________________ Publication No. 7 The Chipko Movement: A Pragmatic, Material & Spiritual Reinterpretation by Julio I. Rodriguez Stimson ©Julio I. Rodriguez Stimson The Chipko Movement: A Pragmatic, Material & Spiritual Reinterpretation Julio I. Rodríguez Stimson Seminar: Environmental Sustainability in South Asia: Historical Perspectives, Recent Debates and Dilemmas Professors: Divya Narayanan & Gita Dharampal-Frick Semester: WiSe 2015/16 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 Long-Term Causes ............................................................................................................ 2 The Chipko Movement ...................................................................................................... 4 The Ideology of Chipko .................................................................................................... 5 Consequences .................................................................................................................... 6 Ecologically Noble Savages, Environmentality and Pragmatism ..................................... 8 Deep Ecology and Spirituality ......................................................................................... -

Women's Non-Violent Power in the Chipko Movement

HERSTQRY SUNDFRLAL BAHUGUNA Protecting The Sources Of Community life Women’s Non-Violent Power In The Chipko Movement The history we read tells us very little of what women were doing during the evolution of “mankind”. We hear of an occasional Nur Jehan or Lakshmibai but what of the millions of ordinary women-how did they live, work and struggle?Women have always participated in social and political movements but their role has been relegated at best to the footnotes of history. This study of the Chipko Movement written by a movement activist, points out the links between women’s burden as food providers and gatherers and thier militancy in defending natural resources from violent devastation. The word Chipko originates front a particular farm of non-violent action developed by hill women in the 19th century forerunner of today’s movement. Women would embrace (chipko) the trees to prevent there being felled, and some women were killed while thus protecting with their own bodies the sources of community life. A CURSORY glance at any newspaper will show that most are women. Women are not allowed to participate in public and of the space is occupied by urban affairs and problems, by the political life. The most important institution in the village is the doings of those in power who are busy making plans and gram panchayat. Hardly ever does one come across a woman policies. Though there is much fancy talk of rural uplift and member of a panchayat. The question of a woman Sarpanch rural welfare, none of these plans solve the problems of the does not of course arise. -

Report on Women and Water

SUMMARY Water has become the most commercial product of the 21st century. This may sound bizarre, but true. In fact, what water is to the 21st century, oil was to the 20th century. The stress on the multiple water resources is a result of a multitude of factors. On the one hand, the rapidly rising population and changing lifestyles have increased the need for fresh water. On the other hand, intense competitions among users-agriculture, industry and domestic sector is pushing the ground water table deeper. To get a bucket of drinking water is a struggle for most women in the country. The virtually dry and dead water resources have lead to acute water scarcity, affecting the socio- economic condition of the society. The drought conditions have pushed villagers to move to cities in search of jobs. Whereas women and girls are trudging still further. This time lost in fetching water can very well translate into financial gains, leading to a better life for the family. If opportunity costs were taken into account, it would be clear that in most rural areas, households are paying far more for water supply than the often-normal rates charged in urban areas. Also if this cost of fetching water which is almost equivalent to 150 million women day each year, is covered into a loss for the national exchequer it translates into a whopping 10 billion rupees per year The government has accorded the highest priority to rural drinking water for ensuring universal access as a part of policy framework to achieve the goal of reaching the unreached. -

A Case Study of Women's Role in the Chipko Movement in Uttar Pradesh Author(S): Shobhita Jain Reviewed Work(S): Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol

Women and People's Ecological Movement: A Case Study of Women's Role in the Chipko Movement in Uttar Pradesh Author(s): Shobhita Jain Reviewed work(s): Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 19, No. 41 (Oct. 13, 1984), pp. 1788-1794 Published by: Economic and Political Weekly Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4373670 . Accessed: 08/11/2011 21:54 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic and Political Weekly. http://www.jstor.org SPECIAL ARTICLES Women and Peoples Ecological Movement A Case Study of Women's Role in the Chipko Movement in Uttar Pradesh Shobhita Jain In the ChipkoMovement, which is concernedwith preservation offorests and maintenanceof the ecologicalbalance in the sub-Himalayanregion, is a social movement,-an important role has been played by women of Garhwal region. The authorcontends that women'sparticipation not only played often a decisiverole, but that consider- ing the specificexistential conditions in the hill regionit was easierfor womento perceivethe needfor preserving the ecological balancein the area. However,the mobilisationof womenfor the cause of preservingforests has broughtabout a situation of conflict regardingtheir own status in society-demand for sharingin the decision- makingprocess-and men'sopposition to this and to women'ssupport for Chipkomovement. -

Catalogue No. 14 of the Papers of Chandi Prasad Bhatt

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue No. 14 Of The Papers of Chandi Prasad Bhatt Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Chandi Prasad Bhatt Gandhian Social Activist Chandi Prasad Bhatt is one of India’s first modern environmentalist. He was born on 23 June 1934. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of peace and non-violence, Chandi Prasad averted deforestation in the Garhwal region by clinging (Chipko) to the trees to prevent them from being felled during the 1970’s. He established the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal (DGSM), a cooperative organization in 1964 at Gopeshwar in Chamoli district, Uttarakhand and dedicated himself through DGSM to improve the lives of villagers. He provided them employment near their homes in forest-based industries and fought against flawed policies through Gandhian non-violent satyagraha. To maintain the ecological balance of the forest, DGSM initiated a number of tree-plantation and protection programmes, especially involving women to re-vegetate the barren hillsides that surrounded them. He created a synthesis between practical field knowledge and the latest scientific innovations for the conservation of environment and ecology in the region. Chandi Prasad Bhatt has been honoured with several awards including Ramon Magsaysay Award for community leadership (1982), Padma Shri (1986), Padma Bhushan (2005), Gandhi Peace Prize (2013), and Sri Sathya Sai Award (2016). Chandi Prasad Bhatt has written several books on forest conservation and large dams: Pratikar Ke Ankur (Hindi), Adhure Gyan Aur Kalpanik Biswas per Himalaya se Cherkhani Ghatak (Hindi), Future of Large Projects in the Himalaya, Eco-system of Central Himalaya, Chipko Experience, Parvat Parvat Basti Basti, etc. -

Geographies That Make Resistance”: Remapping the Politics of Gender and Place in Uttarakhand, India

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 34 Number 1 Article 12 Spring 2014 Geographies that Make Resistance”: Remapping the Politics of Gender and Place in Uttarakhand, India Shubhra Gururani York University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Gururani, Shubhra. 2014. Geographies that Make Resistance”: Remapping the Politics of Gender and Place in Uttarakhand, India. HIMALAYA 34(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol34/iss1/12 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geographies that Make Resistance”: Remapping the Politics of Gender and Place in Uttarakhand, India Acknowledgements I would like to profusely thank the women who openly and patiently responded to my inquiries and encouraged me to write about their struggle and their lives. My thanks also to Kim Berry, Uma Bhatt, Rebecca Klenk, Manisha Lal, and Shekhar Pathak for reading and commenting earlier drafts of the paper. This research article is available in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and -

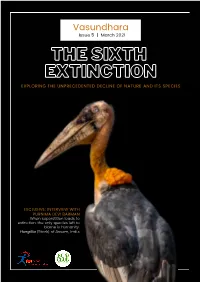

The Sixth the Sixth Extinction

Vasundhara Issue 5 | March 2021 THE SIXTH EXTINCTION EXPLORING THE UNPRECEDENTED DECLINE OF NATURE AND ITS SPECIES EXCLUSIVE: INTERVIEW WITH PURNIMA DEVI BARMAN When superstition leads to extinction, the only species left to blame is humanity. Hargilla (Stork) of Assam, India Eco-Club TERISAS brings to you "The Sixth Extinction", the fifth issue of Vasundhara magazine, on the theme biodiversity and climate change. This is a free and creative initiative to educate young minds about the ongoing events in this field. The information in the magazine is for general use only Editor's Note 4 and has been compiled from various research India's Environmental Commitments: 5 papers/articles/government databases. Some Everything You Need To Know personal experiences and anecdotes have also been shared for which we extend our sincere gratitude to e Climate Change and Disease 6 the contributors. The information given in this edition is accurate to Zoonotic Diseases and Biodiversity 7 the best of our knowledge as of 17th March and we The Battle For Belonging: 8 apologize for any inadvertent errors that may exist. u A Case Study of Mollem, Goa Decoding How Your Next Meal 9 s Can Help Save The Planet At War With Wetlands 10 THE TEAM s Kadar's: Leading The 12 Environmental Cause I The Role of Individuals in 13 EDITORIAL Conserving Biodiversity EDITOR: Kashish Bansal (MA SDP) SUB-EDITOR: Divija Kumari (MA SDP) Where The Wild Things Were 14 MEMBER: Mansi Dave (MA SDP) s MEMBER: Jaya Gupta (PhD. Business Sustainability) Superstition Led Extinction: 16 Interview with Mrs. Purnima Barman MEMBER: Parth Tandon (MSc ESRM) i Lost Paradise 18 The Science of Biodiversity 21 h and Conservation @TERISAS CONTENT EXECUTIVE: Anshita Jindal (MA SDP) Pre/ConServe: 22 Interview with Mr. -

Unit 25 Alternatives

Modern Concern UNIT 25 ALTERNATIVES Structure 25.0 Introduction 25.1 Development – Gandhian Alternatives 25.2 Environmental Conservation – Chipko Movement 25.3 Summary 25.4 Exercises 25.5 Suggested Reading 25.0 INTRODUCTION Development has generally been understood to mean an unfettered march of the material forces to ever escalating heights; always in search of newer areas of progress; and growth of a socio-economic system that is solely guided in its search of fresh pastures by corporeal considerations. Beginning with Industrial Revolution this view of development has dominated the discourse of progress and growth for the past two and a half centuries. In Unit 22 of this Block we have read about environmental concerns occupying a place within this dominant developmental paradigm. The present Unit aims at providing information on the alternative discourse/s to the aforesaid idea of development. We have selected two cases providing alternatives to ‘development’ and ‘environmental conser- vation’ respectively. The cases have been selected with a view to highlight concrete alternatives and feasible processes of developmental and conser- vational transitions in India. 25.1 DEVELOPMENT – GANDHIAN ALTERNATIVES The development priorities of India and their viability began to be considered seriously as a realistic proposition in the foreseeable future by the leadership in national movement in the 1920s. As the prospects of independence became brighter the discussions on developmental model for independent India too became intense and elaborate. There were now two major protagonists – Gandhi and Nehru who supported two different models. While Gandhi was of the firm view that the road to development charted its path through the villages of India, Nehru was a strong votary of modern, industrial model of development. -

CHIPKO MOVEMENT of GARHWAL Gaura Devi HIMALAYA, INDIA

CHIPKO MOVEMENT OF GARHWAL Gaura Devi HIMALAYA, INDIA The ‘Chipko movement’ is a movement that followed Gandhian method of non-violent resistance though the act of hugging trees to protect them from being felled. The Chipko movement started in early 1970 in the Garhwal Himalayas of Uttarakhand (the then U.P). The landmark event took place on 26 March, 1974 when a group of peasant women of Reni village in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand acted to prevent the cutting of trees and reclaim their traditional forest rights. Their actions inspired hundreds of such actions which spread throughout India. It led to the formulation of people sensitive policies which put a stop on the open felling of trees. The Chipko movement, which was also a livelihood movement, created a precedent for non- violent protest. It occurred at a time when there was hardly any environmental movement in the developing world. This non-violent movement was immediately noticed worldwide which inspired many eco-groups to slow down the rapid deforestation, increase ecological awareness, and demonstrate the viability of people power. A quarter century later, India today has mentioned the people behind the “Forest satyagraha” of the Chipko movement as amongst “100 people who shaped India”. On March 26, 2004, Reni, Laata, and other villages of the Niti Valley celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Chipko Movement, where all the surviving original participants united. The celebrations started at Laata, the ancestral home of Gaura Devi, one of the leaders of Chipko movement. Designed & Printed at Shiva Offset Press, Dehradun Ph. 0135-2715748 mRrjk[k.M tSofofo/krk cksMZ UTTARAKHAND BIODIVERSITY BOARD Uttarakhand Biodiversity Board | 108, Phase-II, Vasant Vihar, Dehradun (Uttarakhand) INDIA Tel/Fax: +91-135-2769886 | E-mail: [email protected] | Website: www.ukbiodiversity.org. -

Sunderlal Bahuguna and Chipko Movement

22 May, 2021 Sunderlal Bahuguna and Chipko Movement The 94-year-old environmentalist succumbed to Covid-19 on May 21, 2021, at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Rishikesh, Uttarakhand. With his demise, India has lost one of the finest environmentalists and social workers who had also been part of India’s freedom movement. About Sundarlal Bahuguna Born in village Maroda near Tehri, Uttarakhand on January 9, 1927, he was an active revolutionary during Indian Freedom Struggle. Early in his life, Sunderlal Bahuguna met Gandhian Sridev Suman, who later died while on a long fast of 84 days against the atrocities of Tehri’s king, and that made a deep impression on Bahuguna. It moulded his political and social understanding. He vowed to work for the weak and powerless in a non- violent manner and practised what he preached. He adopted Gandhian principles in his life. Inspired by Gandhi, he walked through Himalayan forests and hills, covering more than 4,700 kilometres on foot and observed the damage done by mega developmental projects on the fragile ecosystem of the Himalayas and subsequent degradation of social life in villages. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi, he fought against untouchability and to do so in true spirit he lived with Dalits (formerly untouchables) in the same house and ate with them. He was also part of the anti-liquor movement in the 1960s and of course, you can’t forget the sarvodayi movement he actively participated in,” Sarvodayi movement is rooted in Gandhian philosophy of upliftment of all. He fought for the preservation of forests in the Himalayas, first as a member of the Chipko movement in the 1970s which started in Chamoli district, and later spearheaded the anti-Tehri Dam movement from the 1980s to early 2004.