Thesis Amended to Examiners Comments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extract Catalogue for Auction 3

Online Auction 3 Page:1 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 Balance of collection including 1931-71 fixtures (7); Tony Locket AFL Goalkicking Estimate A$120 Record pair of badges; football cards (20); badges (7); phonecard; fridge magnets (2); videos (2); AFL Centenary beer coasters (2); 2009 invitation to lunch of new club in Reserve A$90 Sydney, mainly Fine condition. (40+) Lot 959 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 959 Balance of collection including Kennington Football Club blazer 'Olympic Premiers Estimate A$100 1956'; c.1998-2007 calendars (21); 1966 St.Kilda folk-art display with football cards (7) & Reserve A$75 Allan Jeans signature; photos (2) & footy card. (26 items) Lot 960 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 960 Collection including 'Mobil Football Photos 1964' [40] & 'Mobil Footy Photos 1965' [38/40] Estimate A$250 in albums; VFL Park badges (15); members season tickets for VFL Park (4), AFL (4) & Reserve A$190 Melbourne (9); books/magazines (3); 'Football Record' 2013 NAB Cup. (38 items) Lot 961 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 961 Balance of collection including newspapers/ephemera with Grand Final Souvenirs for Estimate A$100 1974 (2), 1985 & 1989; stamp booklets & covers; Member's season tickets for VFL Park (6), AFL (2) & Melbourne (2); autographs (14) with Gary Ablett Sr, Paul Roos & Paul Kelly; Reserve A$75 1973-2012 bendigo programmes (8); Grand Final rain ponchos. (100 approx) Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au 20 - 23 November 2020 Lot 962 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 962 1921 FOURTH AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CARNIVAL: Badge 'Australian Football Estimate A$300 Carnival/V/Perth 1921'. -

AFL Coaching Newsletter - April 2009

AFL Coaching Newsletter - April 2009 THE NEW SEASON Most community football leagues around Australia kick off this weekend or immediately after Easter and NAB AFL Auskick Centres commence their programs in the next month. This newsletter focuses on a range of topics which are relevant to the commencement of the 2009 Australian Football season. PLAYING AND TRAINING IN HOT CONDITIONS The new season generally starts in warm to hot conditions and there is always a lift in intensity once the premiership season proper starts. Regardless of the quality of pre-season training programs, early games are usually more stressful and players and coaches should keep safety factors associated with high intensity exercise in warm conditions in mind – these include individual player workloads (use of the bench), hydration and sun sense. The following article by AIS/AFL Academy dietitian Michelle Cort provides good advice regarding player hydration. Toughen Up - Have a Drink! Why are so many trainers necessary on a senior AFL field and why they are constantly approaching players for a drink during a game? Obviously the outcome of not drinking enough fluid is dehydration. The notion of avoiding fluid during sport to ‘train’, ‘toughen’ or ‘adjust’ an athlete’s body to handle dehydration is extremely outdated & scientifically incorrect. Even very small amounts of dehydration will reduce an AFL player’s performance. Most senior AFL conditioning, nutrition and medical staff invest considerable time into ensuring the players are doing everything possible to prevent significant dehydration from occurring in training and games. The effects on performance are not limited to elite athletes. -

Get Book // Fitzroy Football Club Players

SXZMPDXHX4TU # PDF ^ Fitzroy Football Club players Fitzroy Football Club players Filesize: 8.29 MB Reviews This book can be worthy of a read, and much better than other. It usually fails to charge a lot of. I realized this publication from my dad and i encouraged this pdf to understand. (Prof. Flo Cruickshank DDS) DISCLAIMER | DMCA FHLR2DOZS7CC ~ eBook « Fitzroy Football Club players FITZROY FOOTBALL CLUB PLAYERS Reference Series Books LLC Aug 2014, 2014. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x187x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 101. Chapters: List of Fitzroy Football Club players, Stan Reid, Norm Smith, Jack Worrall, Paul Roos, Don Chipp, Jack Cooper, Douglas Nicholls, Haydn Bunton, Sr., Nick Carter, Robert Walls, Alastair Lynch, Ross Lyon, Allan Ruthven, Matthew Primus, Ted McDonald, Len Thompson, Martin Pike, Grant Thomas, Frank Curcio, Dale Kickett, John Leckie, John Barker, Chris Johnson (Australian footballer, born 1976), John Murphy, Norm Johnstone, Scott Bamford, Garry Sidebottom, Bernie Quinlan, Vic Chanter, Richard Osborne, Doug Hawkins, Wilfred 'Chicken' Smallhorn, Bill Adams, Kevin Murray, Garry Wilson, John Blair, Paddy Shea, Colin Benham, Fred Hughson, Jack Moriarty, Matt Rendell, Peter Sartori, Joe Johnson, Alan Gale, Jim Atkinson, Ron Alexander, Gary Pert, Simon Atkins, Graham Ramshaw, Lawrence Morgan, Terry O'Neill, Len Pye, Stephen Paxman, Bill Stephen, Clen Denning, Len Smith, Jack Cashman, Brad Gotch, Len Toyne, Wally Matera, Ken Hinkley, Ken Grimley, John Rombotis, Scott McIvor, Trent Cummings, Jimmy Freake, -

By RDFL Operations Manager Toby Boyle ACROSS MY DESK

Round 15 SATURDAY AUGUST 1ST 2015 ACROSS MY DESK by RDFL Operations Manager Toby Boyle Welcome to Round 15 of the RDFNL Season. Just over • Invested heavily to host a training session in 2014 that a month left until we enter the 2015 Finals Series and all RDFNL Senior Clubs attended which included this week we commence the first of two multi-bye training on the need to create an environment that weekends where a number of clubs will rest up before is a warm and welcoming environment to people the onslaught of finals footy and netball. from all backgrounds regardless of sex, race, religion, RDFNL Celebrates Multicultural Round country of birth, skin colour, etc. The RDFNL is proud to bring you our very own version • Introduction of a Racial, Religious and Sexual of Multicultural Round. This round has been developed Orientation policy in 2012, to outline the important role that Multicultural • Committed to provide further training for club communities play within the AFL Goldfields Region and members that includes modules on vilification and the importance of our clubs creating an all-inclusive discrimination, cyber safety, alcohol, smoking and environment to encourage people of all backgrounds to drugs, respect and responsibility and mental health. participate in both football and netball. In addition to the above, and in an effort to try and The RDFNL Multicultural Round is a themed round to achieve the warm and welcoming environment for acknowledge and celebrate players who fall into the players and supporters from all backgrounds, AFL category of a multicultural player and also helps us Goldfields has created our own No“ Limits United to acknowledge and celebrate our game’s cultural Through Sport” advertising program that celebrates the diversity. -

Media Release from the Australian Football League

MEDIA RELEASE FROM THE AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE The AFL today wrote to all clubs to advise the AFL Commission had approved a change to the 22-match fixture structure whereby each club would now have two byes through the season comprising 22 matches across 25 weeks, starting from next year’s 2014 Toyota AFL Premiership Season. As part of the introduction of a second bye to better manage the workload on players and clubs throughout the year, the premiership season will now commence with a split round across the weekends of March 14-16 and March 21-23 (five matches and four matches respectively on those two weekends). The pre-season period will be revitalised to feature two matches per Club scheduled nationally, with a continued focus on regional areas that don’t normally host premiership matches, as well as matches in metropolitan areas and managing the travel load across all teams. In place of the NAB Cup Grand Final, the AFL is currently considering options for a representative-style game in the final week of the pre-season, together with intra-club matches for all teams, before round one gets underway. AFL General Manager - Broadcasting, Scheduling and Major Projects Simon Lethlean said the first group of club byes were likely to be across rounds 8-10 (three weeks of six matches per round) with the second group of club byes to be placed in the run to the finals in the region of rounds 18-19 (one week of five matches and one week of four matches). All up, clubs would each play 22 games across 25 weeks through March 14-16 (week one of round one) to August 29-31. -

Xref Aust Catalogue for Auction

Page:1 Oct 20, 2019 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 19th Century Lot 44 44 1880 Australian Team original photograph 'The Australian Eleven, 1880', size 17x11cm, with players names on mount. Superb condition. 300 Lot 45 45 1893 Australian Team Carte-de-visite photograph 'Eighth Australian Cricketing Team, 1893', with players names on mount, published by London Stereoscopic Photographic Co. 500 Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au Oct 20, 2019 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1901 to 1927 Ex Lot 46 46 Postcards 'V.Trumper (NSW)' fine used in UK 1905; 'The Australian Cricketers in England, 1912' fine mint; 'Australian Cricket Team 1921' fine mint. (3) 150 Page:3 Oct 20, 2019 CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1901 to 1927 (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Ex Lot 47 47 1901-02 Australian Team original photograph of team for the First Test at the SCG, most players wearing their Australian caps and blazers, size 26x18cm; also photograph of the giant scoreboard erected on the 'Evening News' building; and a third photograph of the crowd watching the scoreboard. Fine condition. (3) 700 Page:4 www.abacusauctions.com.au Oct 20, 2019 CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1901 to 1927 (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Lot 48 48 COLLINGWOOD CRICKET CLUB: Team photograph '1906-7' with players & committee names on mount, noted TW Sherrin, EW Copeland (after whom the Collingwood FC best & fairest is named) & a very young Jack Ryder (who was Bradman's captain in his first Test 22 years later), framed (no glass), overall 92x77cm, some faults at top right. -

Encyclopedia of Australian Football Clubs

Full Points Footy ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CLUBS Volume One by John Devaney Published in Great Britain by Full Points Publications © John Devaney and Full Points Publications 2008 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Every effort has been made to ensure that this book is free from error or omissions. However, the Publisher and Author, or their respective employees or agents, shall not accept responsibility for injury, loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this book whether or not such injury, loss or damage is in any way due to any negligent act or omission, breach of duty or default on the part of the Publisher, Author or their respective employees or agents. Cataloguing-in-Publication data: The Full Points Footy Encyclopedia Of Australian Football Clubs Volume One ISBN 978-0-9556897-0-3 1. Australian football—Encyclopedias. 2. Australian football—Clubs. 3. Sports—Australian football—History. I. Devaney, John. Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net Introduction For most football devotees, clubs are the lenses through which they view the game, colouring and shaping their perception of it more than all other factors combined. To use another overblown metaphor, clubs are also the essential fabric out of which the rich, variegated tapestry of the game’s history has been woven. -

Australian Football League ABN 97 489 912 318 Modern Slavery

Australian Football League ABN 97 489 912 318 Modern Slavery Statement For the Reporting Period 1 November 2019 to 31 October 2020 This is the first Modern Slavery Statement (Statement) of the Australian Football League (ABN 97 489 912 318) (AFL), an Australian public company incorporated in Victoria, and its subsidiaries made to address the requirements of the Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth) (Act). This statement highlights the assessment and action that the AFL has taken to identify, manage and mitigate the risks of modern slavery in our business operations and supply chain. The AFL takes its obligations in relation to addressing modern slavery risks in its business operations and supply chain very seriously and has a zero-tolerance approach. The AFL is committed to implementing processes and controls in our business practices to ensure the risks of all forms of modern slavery are eliminated from our operations and supply chains and that our business practices are conducted ethically. About the AFL The AFL is the governing body of the sport of Australian Football. It administers both the elite Men’s and the Women’s Australian Football competitions and talent pathways to reach those competitions. The AFL was previously named the Victorian Football League. It changed its name to the Australian Football League in 1990 to reflect the expansion of the elite Men’s competition, which now has a national footprint, with matches played each season in every State and Territory in Australia. The elite Men’s competition is now made up of 18 Clubs (AFL Clubs). The first season of the elite Women’s Australian football competition, also known as AFLW, was completed in 2017. -

![12/05/2005 Case Announcements #2, 2005-Ohio-6408.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3450/12-05-2005-case-announcements-2-2005-ohio-6408-1143450.webp)

12/05/2005 Case Announcements #2, 2005-Ohio-6408.]

CASE ANNOUNCEMENTS AND ADMINISTRATIVE ACTIONS December 5, 2005 [Cite as 12/05/2005 Case Announcements #2, 2005-Ohio-6408.] MISCELLANEOUS ORDERS On December 2, 2005, the Supreme Court issued orders suspending 13,800 attorneys for noncompliance with Gov.Bar R. VI, which requires attorneys to file a Certificate of Registration and pay applicable fees on or before September 1, 2005. The text of the entry imposing the suspension is reproduced below. This is followed by a list of the attorneys who were suspended. The list includes, by county, each attorney’s Attorney Registration Number. Because an attorney suspended pursuant to Gov.Bar R. VI can be reinstated upon application, an attorney whose name appears below may have been reinstated prior to publication of this notice. Please contact the Attorney Registration Section at 614/387-9320 to determine the current status of an attorney whose name appears below. In re Attorney Registration Suspension : ORDER OF [Attorney Name] : SUSPENSION Respondent. : : [Registration Number] : Gov.Bar R. VI(1)(A) requires all attorneys admitted to the practice of law in Ohio to file a Certificate of Registration for the 2005/2007 attorney registration biennium on or before September 1, 2005. Section 6(A) establishes that an attorney who fails to file the Certificate of Registration on or before September 1, 2005, but pays within ninety days of the deadline, shall be assessed a late fee. Section 6(B) provides that an attorney who fails to file a Certificate of Registration and pay the fees either timely or within the late registration period shall be notified of noncompliance and that if the attorney fails to file evidence of compliance with Gov.Bar R. -

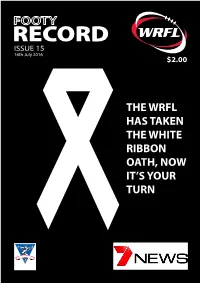

RECORD ISSUE 15 16Th July 2016 $2.00

RECORD ISSUE 15 16th July 2016 $2.00 THE WRFL HAS TAKEN THE WHITE RIBBON OATH, NOW IT’S YOUR TURN ‘Protect your players with the best’ » Largest range of strapping tapes and medical supplies » Used by Clubs and Leagues for over 15 years » Rewards packages available Club Warehouse is the leading Sports Medical Supplier, »Taping Supplies offering an extensive range of quality sports medical supplies. »Sports Nutrition & Hydration Discuss with us your budget options and we can provide »Rehabilitation product solutions suited to your needs. »S upports and Bracing » First Aid Supplies Proudly chosen medical supplier for: »Sports Performance » EDFL, EFL, SFL, WRFL, VAFA, AFL VIC, 14 AFL CLUBS. Call us today to experience the Club Warehouse difference! P: +3 8413 3100 M: +61 413 576 677 E: [email protected] ‘Official Suppliers’ KICKIN’ IT WITH KRISTEN Editorial – Issue 15, July 16th 2016 THE WRFL’S WHITE RIBBON OATH By KRISTEN ALEBAKIS THIS week the Western If you haven’t already seen it, please visit the WRFL Region Football League website or Facebook page to view the video. released a White Ribbon Also in this week’s edition of the Record we find out video featuring players what you can do if you witness a violent act or what to from across the league. do when you are aware of violence happening, either The aim of the video and the during or after the incident. WRFL’s White Ribbon Round Turn to page 3 for more White Ribbon information. is to create awareness to end men’s violence against I also wanted to congratulate the seven players from the women. -

No Sign of Home Sickness Get Ready to Pounce!

CHAMPION/DATA/ISSUE 16 Hi and welcome to the sixteenth edition of the Fantasy Freako’s rave for 2011. We dodged a bullet last round with news that Gary Ablett’s knee injury isn’t as bad as first thought. He’s now an outside chance to face Richmond this week, which would relieve the thousands of coaches that traded him in last round. Enjoy this week’s rave and good luck to everyone for the upcoming round. NO SIGN OF HOME SICKNESS GET READY TO POUNCE! It’s one thing to perform on your home deck, but to do it away from With most of us close to finalising our sides, it’s vital that we bring home as well is an added bonus. With interstate travel a key component in the right player’s at the right price. Looking at the approximate for every AFL player, looking at player’s that fire on their travels has breakevens for this round, Drew Petrie is one player to keep a close eye proven to be an interesting exercise. For the purpose of this analysis, only those that have played in more than one match have been included, on in the wake of his dismal performance against Collingwood, where which explains why Travis Cloke doesn’t appear with his 136 points, as he finished with a season-low 24 points. Gary Ablett should always be his game against Sydney in Round 14 has been his only interstate trip. a target, and the little master will need to produce something special against Richmond this week, if indeed he actually plays, to keep his If we look at the best performers across the season, it’s no surprise that price. -

The Story of Jim and Phillip Krakouer. by Sean Edward Gorman BA

Moorditj Magic: The Story of Jim and Phillip Krakouer. By Sean Edward Gorman BA (Hons) Murdoch University A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At Murdoch University March 2004 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work, which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………. Sean Edward Gorman. ii ABSTRACT This thesis analyses and investigates the issue of racism in the football code of Australian Rules to understand how racism is manifested in Australian daily life. In doing this, it considers biological determinism, Indigenous social obligation and kinship structure, social justice and equity, government policy, the media, local history, everyday life, football culture, history and communities and the emergence of Indigenous players in the modern game. These social issues are explored through the genre of biography and the story of the Noongar footballers, Jim and Phillip Krakouer, who played for Claremont and North Melbourne in the late 1970’s and 1980’s. This thesis, in looking at Jim and Phillip Krakouers careers, engages with other Indigenous footballer’s contributions prior to the AFL introducing Racial and Religious Vilification Laws in 1995. This thesis offers a way of reading cultural texts and difference to understand some Indigenous and non-Indigenous relationships in an Australian context. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have often wondered where I would be if I had not made the change from work to study in 1992. In doing this I have followed a path that has taken me down many roads to many doors and in so doing I have been lucky to meet many wonderful and generous people.