General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

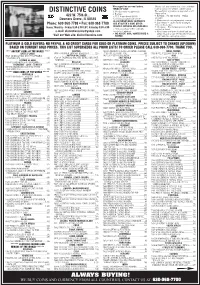

Distinctive Coins |

We suggest fax or e-mail orders. Please call and reserve the coins, and then TERMS OF SALE mail or fax us the written confirmation. DISTINCTIVE COINS 1. No discounts or approvals. We need your signature of approval on all 2. Postage: charge sales. 422 W. 75th St., a. U.S. insured mail $5.00. 4. Returns – for any reason – within b. Overseas registered $20.00. 21 days. Downers Grove, IL 60516 5. Minors need written parental consent. ALL INTERNATIONAL SHIPMENTS 6. Lay Aways – can be easily arranged. Phone: 630-968-7700 • Fax: 630-968-7780 ARE AT BUYER’S RISK! OTHER Give us the terms. Hours: Monday - Friday 9:30-5:00 CST; Saturday 9:30-3:00 INSURED SERVICES ARE AVAILABLE. 7. Overseas – Pro Forma invoice will be c. Others such as U.P.S. or FedEx mailed or faxed. e-mail: [email protected] need street address. 8. Most items are one-of-a-kind and are 3. WE ACCEPT VISA, MASTERCARD & subject to prior sale. Distinctive Coins is Visit our Web site: distinctivecoins.com PAYPAL! not liable for cataloging errors. PLATINUM & GOLD BUYERS: NO PAYPAL & NO CREDIT CARDS FOR GOLD OR PLATINUM COINS. PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE (UP/DOWN) BASED ON CURRENT GOLD PRICES. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL PRIOR LISTS! TO ORDER PLEASE CALL 630-968-7700. THANK YOU. **** ANCIENT COINS OF THE WORLD **** AUSTRIA 1891A 5 FRANCOS K-12 NGC-AU DETAILS CLEANED INDIA, MEWAR GREECE-CHIOS 1908 5 CORONA K-2809 NGC-MS63 60TH .............225 1 YR TYPE PLEASANT TONE .................................380 1928 RUPEE Y-22.2 NGC-MS64 THICK ...................110 (1421-36) DUCAT NGC-MS61 -

An Important Collection of French Coins

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AN IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF FRENCH COINS Essais and Piedforts 2001 Republic, Copper Essai Monneron Monnaie de Confiance 2-Sols, Year 1, 1792, by Dupré, Hercules kneeling breaking royal sceptre, owl behind, rev pyramid, plain edge, 15.40g, 32mm (as VG 342, but plain edge; Maz 332a; Reynaud 8a). Extremely fine. £150-200 2002 Louis Philippe (1830-1848), Bronze Essai 3-Centimes and 2-Centimes, undated (1831-1842), by Domard, first with -

Swiss Money Secrets

Swiss Money Secrets Robert E. Bauman JD Jamie Vrijhof-Droese Banyan Hill Publishing P.O. Box 8378 Delray Beach, FL 33482 Tel.: 866-584-4096 Email: http://banyanhill.com/contact-us Website: http://banyanhill.com ISBN: 978-0-578-40809-5 Copyright (c) 2018 Sovereign Offshore Services LLC. All international and domestic rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher, Banyan Hill Publishing. Protected by U.S. copyright laws, 17 U.S.C. 101 et seq., 18 U.S.C. 2319; Violations punishable by up to five year’s imprisonment and/ or $250,000 in fines. Notice: this publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold and distributed with the understanding that the authors, publisher and seller are not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional advice or services. If legal or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional adviser should be sought. The information and recommendations contained in this brochure have been compiled from sources considered reliable. Employees, officers and directors of Banyan Hill do not receive fees or commissions for any recommendations of services or products in this publication. Investment and other recommendations carry inherent risks. As no investment recommendation can be guaranteed, Banyan Hill takes no responsibility for any loss or inconvenience if one chooses to accept them. -

Juro SEC Registrations and Listings Sheets-Juro Series

EXHIBIT “B” Table of All Series at the time of the Making of the Juro Organization Minimum # of NAV per Unit Series Asset per Basket using USD NAV per Juro Underlying Currency / Underlying Underlying Fractional # of Fractional Series # Symbol / for Issuance Exchange Rate on Basket on Quotation / Valuation Index / Peg Quotation of NAV Commodity / Asset Class Symbol ISO Code Unit Units of Asset Series ID (only issued in 09/05/19 09/05/2019 whole units) (1 Unit in USD) 1 United States Dollar $ USD §$ Cent 100 10 $1.0000 $10.0000 1 to 1 with USD in USD as per Index / Peg CME FX Futures or if no CME in USD as per Index / Peg to 2 decimal places (3rd and 2 Euro € EUR §€ Cent 100 10 $1.0970 $10.9700 Quotation then Cash FX fourth place amounts are always rounded down) CME FX Futures or if no CME in USD as per Index / Peg to 2 decimal places (3rd and 3 British Pounds Sterling £ GBP §£ Penny 100 10 $1.2099 $12.0990 Quotation then Cash FX fourth place amounts are always rounded down) CME FX Futures or if no CME in USD as per Index / Peg to 2 decimal places (3rd and 4 Swiss Franc Fr. CHF §Fr. Centime 100 10 $1.0132 $10.1320 Quotation then Cash FX fourth place amounts are always rounded down) CME FX Futures or if no CME in USD as per Index / Peg to 2 decimal places (3rd and 5 Japanese Yen ¥ JPY §¥ Sen 100 1,000 $0.0094 $9.4000 Quotation then Cash FX fourth place amounts are always rounded down) CME FX Futures or if no CME in USD as per Index / Peg to 2 decimal places (3rd and Afghan Afghani ؋ AFN §AFN Pul 100 1,000 $0.0128 $12.8000 6 Quotation then -

Philatelic Currencies

Philatelic Currencies The 228 currencies hidden in this puzzle all appear on stamps of the past 175+ years R S K Y A Q E A M H C A R D A L L A E B S A H A K R O N E L U I L C P F U Y U O G A V A N O R K I Y U A N T P Z Y I P W P A D R E Z U E R K U E N O I S O R G U R T T I B I S A L E E A T N S P I D T I A O G A K K R A M E U R U O Y Z L O T Y E K I P E Q O U E Z R A U I D E Y M T A K S L T T I B R R U I N H S T B K K H O A T L U F I L S E C L U M A K U T A V G G E O D A Z U R C Y N L T A U M A A E H C R E U G K R P H E S R A L O D Y E A E I R R G T I R N H R I O T L O M L P A T B E G A A V A D C N D T U H P S T T D E T A I R E H E E L E B D N Y N R C L G O H O M I L E S I M O M S C T M N K N E I Y R A I R A L I A I N O M O S T U M A G L I A M N A E C R R Z U A R T V R U N S N A Z I I N A H S H I L L I N G H E U T L O P U A I S G G S I A M I S E L I M L L N A L P P S R P E H G M F S L P A O O G O H O N C R U P I A J N R I N G G I T G T I I N O O R K R R W E G T K H U K R N W F E O M E I A D N K L Y T B U G E G O G R S F Y L I C A G R E I F G A L H Y K P W A L N L B N N A T O A T A L P L A E R K S L P A R N N D E S A K Y E Y P A K N I T O T S I S L N N O Q E L C N K O E S B U C A P C Z T Y A C I N A B I A E I D I S A P E C N N N O L O C H T N T A I E F L A M E D A T N N A H C P M R G A A M D O B R A N A S P L P C I R S E N B D T G R A H E W O F R O L E K W E L E L O T I A V G I O V A T N E C E A E C E P F Y U U K S I D M R K C R Q I N T A R A L L O D C E T N A B M R N E F M G E I P V I S R L S K K L I A A O D L Z N T E M O A A F O R I -

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

Victor Schoelcher's Views on Race and Slavery

This dissertation has been 65-13,290 microfilmed exactly as received W E L B O R N , Jr., Max, 1928- VICTOR SCHOELCHER'S VIEWS ON RACE AND SLAVERY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1965 History, mo d e m University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan VICTOR SCHOELCHER'S VIEWS ON RACE AND SLAVERY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Max Welbom, Jr., B.A., M.A. *♦♦♦♦♦♦♦ The Ohio State University 1965 Approved by Adviser Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge the assistance rendered by the staffs of the following libraries: the RLbliotheque Nationale, BLbliotheque d'Outre-Mer and the Archives du Ministere des Colonies in Paris J The Ohio State University, Miami University, University of Cincinnati, Wilberforce College, and Cleveland Public Libraries in the United States. I should also acknowledge the valuable help offered me in Paris during the research phase of this dissertation by Professor Aaron Noland of the City College of New York, and by Miss Mary Storer, an American resident in Paris. Above all, I am indebted to tty adviser, Professor Robert H. Bremner of The Ohio State University, whose services in connection with this dissertation were of inestimable value. ii VITA October 12, I928 B o m - New York, New York 195 1............ B.A., Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 1952 ••••••• M.A., University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania I 9 5 7 . I 9 5 9 ........ Graduate Assistant, Department of History, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1959-1961....... -

The Monetary Convention of the 6Th of November 1885, Agreed Upon by the Delegates of the Latin Monetary Union

Volume II The Heyday of the Gold Standard, 1820-1930 1885 November 6 The Monetary Convention of the 6th of November 1885, agreed upon by the delegates of the Latin Monetary Union. At the urging of the Swiss government, France, Italy, Greece and Switzerland created a monetary union with interchangeable gold and silver currencies. The union had been in incipient form since 1865. Spain, Bulgaria, Romania, and Serbia all adhered to the Union while never officially joining. also allowed the franc to circulate. The role of silver decreased within the system an it effectively became a monometallic system within a few years. The system was suspended during the First World War and eventually ceased to function in 1926. ——— ARTICLE I. France, Greece, Italy, and Switzerland remain constituted a union in respect to the fineness, weight, diameter, and currency of their specie coined of gold and of silver. ARTICLE II. The types of gold coins bearing the impress of the high contracting parties are those of the 100-franc, 50-franc, 20-franc, 10-franc, and 5-franc pieces, fixed in respect to fineness, weight, tolerance and diameter as follows: Fineness. Weight. Denomination Legal Tolerance Legal Tolerance Diameter. s. standard. above and standard. above and below. below. Thousandths. Thousandths. Grams. Thousandths. Millimeters. Gold: 100 francs 32,258.06 1 35 50 francs 16,129.03 28 20 francs 900 1 6,451.61 2 21 10 francs 3,225.80 19 5 francs 1,612.90 3 17 [Note: In the column for ‘Diameter’, the original mistakenly reads ‘Thousandths’ instead of ‘Millimeters’, but the error has been corrected in this transcription.] 60 Volume II The Heyday of the Gold Standard, 1820-1930 The contracting Governments shall receive, without distinction, at their public treasuries, gold pieces coined in accordance with the foregoing conditions by either of the four states; they may, however, reject coins reduced in weight by abrasion one-half of one per cent. -

FRENCH GOLD in WWI French Replacement of Gold Coins by Paper Money During WWI by Tony James In, People Look for Security

FRENCH GOLD IN WWI French replacement of gold coins by paper money during WWI by Tony James in, people look for security. The search for safe investments becomes all con- suming and for thousands of years, gold has been a popular haven. Natu- rally this search for a safe investment also extends to governments and in 1914 the French government was no exception. Before the First World War comm- enced, the Bank of France had printed notes for the equivalent of 1.5 billion French francs to cover initial war expen- ses and also increased its gold reserves. Another law rendered the currency notes of the Bank of France inconvert- ible, to prevent the stampede by depos- itors to their banks and claiming the gold that backed their banknotes that were issued by the Bank of France. Mademoiselle Marguerite Thibary had managed to acquire some 30 francs in gold coins by early July 1915 and she felt it was her patriotic duty to take the coins to the Bank of France and exchange them for banknotes. She received a rather plain insignificant receipt for her efforts, plus of course her 30 francs in banknotes The poster of the gold coin crushing the German soldier shows what the Bank of France wanted was to issue a 10 franc banknote similar to the one opposite and withdraw the 10 franc gold coin. Interestingly the gold coin is dated 1915, however none with this design were minted after 1914. To illustrate the comparative value of the franc in 1914 to today; in 1914 there were 5 francs to the US dollar and one dollar had the buying power of $20 today. -

Auction 27 | January 19-22, 2017 | Session C

World Coins Session C Begins at 09:00 PST on Friday, January 20, 2017 961. BURMA: Mindon, 1853-1878, AV 2 mu 1 pe (2.89g), CS1228 (1866), KM-20, Chinze dog on obverse, EF $600 - 700 World Coins Asia & Middle-East 962. BURMA: copper-nickel 50 pyas, 1952, KM-36, lovely golden toning, NGC graded PF65 CAM, RR $1,200 - 1,500 Mintage of just 100 pieces, and this is likely one of the finest surviving examples. 957. AFGHANISTAN: Amanullah, 1919-1929, AV 2 amani, SH1299, KM-888, nice strike, AU $350 - 425 963. BURMA: Mindon, 1852-1878, AR kyat (rupee), CS1214 (1852), KM-10, 40mm, enameled and set in sterling handmade bezel pin back brooch hallmarked “L&W”, an active maker in 958. AJMAN: Rashid Bin Humaid al-Nuaimi, 1928-1981, Birmingham in the 1890s, EF $400 - 500 AR 10 riyals, ND (1970), KM-9.1, Centennial of Vladimir Lenin’s The enamel work depicts a magnificent rendition of the peacock Birth, matte finish, NGC graded MS65, R $500 - 600 in seven colors, and is one of the most artistic enameled pieces that we have encountered. The enamel is in pristine condition, and the overall effect is quite lovely. Easily the finest example of this type yet offered. 964. CAMBODIA: Norodon I, 1859-1904, BI 6 fuang (4.41g), ND (1885), Daniel-100a, mintage of only 5,000, a superb example 959. AJMAN: Rashid Bin Humaid al-Nuaimi, 1928-1981, of this rare type with full silver wash still intact, minor stain on AR 7½ riyal, 1970/AH1390, KM-13, Death of President Gamal obverse, choice AU, RR $800 - 1,000 Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Proof $100 - 125 A similar piece sold in Stephen Album Auction 16, Lot 1361, for $1700. -

A List of the Coins in the 100 Different Countries

ECC CODE: DCCN100 100 Coins from 100 Countries Bag Country Denomination Bag Country Denomination A ALBANIA 1 LEK C KIRIBATI 5 CENTS A ANDORRA 1 CENTIME C KOREA NORTH 1/2 CHON A ARGENTINA 1 CENTAVO C KYRGYZSTAN 10 TIYIN A ARMENIA 20 LUMA C LAOS 50 ATT A AUSTRIA 2 EURO CENTS C LATVIA 1 SANTIM A BAHAMAS 1 CENT C LESOTHO SENTE A BAHRAIN 10 FILS C LIBERIA 5 CENTS A BELGIUM 50 CENTIMES C LITHUANIA 2 CENTAI A BERMUDA 1 CENT C MACAO 10 AVOS A BOLIVIA 2 CENTAVOS C MALTA 1 CENT A BOTSWANA 5 THEBE C MALAWI 2 TAMBALA A BRAZIL 50 CENTAVOS C MOLDOVA 1 BAN A BULGARIA 1 STOTINKA C MOZAMBIQUE 20 CENTAVOS A CAPE VERDE 1 ESCUDO C NAGORNO - KARABAKH 1 DRAM A CHINA 1 JIAO C NAMIBIA 5 CENTS A CHINA 5 CHIAO C NETH.ANTILLIES 1 CENT A CONGO D.R. 10 SENGIS C NICARAGUA 5 CENTAVOS A COOK ISLANDS 5 CENTS C PANAMA 1 CENTESIMO A CROATIA 2 LIPE C PARAGUAY 10 GUARANIES A CYPRUS 1 CENT C PERU 5 CENTIMOS A CZECH REPUBLIC 10 HALERU C PHILIPPINES 10 CENTIMOS A DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 25 CENTAVOS C POLAND 1 ZLOYTCH A EAST CARIBBEAN 2 CENTS C QATAR 5 DIRHIM A ECUADOR 1 SUCRE C ROMANIA 10 LEI A EGYPT 1 MILLIEME C RUSSIA 1 KOPEK B EL SALVADOR 5 CENTAVOS D SAMOA 2 SENE B ERITREA 10 CENTS D SAUDI ARABIA 5 HALALA B ESTONIA 10 SENTI D SEYCHELLES 1 CENT B ETHIOPIA 1 CENT D SIERRA LEONE 10 LEONE B FALKLAND ISLAND PENNY D SLOVAK REPUBLIC 10 HALERU B FINLAND 1 PENNIA D SLOVENIA 1 TOLAR B GAMBIA 1 BUTUT D SOMALIA 10 SHILLINGS B GEORGIA 1 TETRI D SOMALILAND 5 SHILLINGS B GERMANY 1 EURO CENT D SOUTH AFRICA 1 CENT B GHANA 1 CEDI D ST. -

Coinage Stamps Issued in Madagascar 1916

COINAGE STAMPS ISSUED IN MADAGASCAR 1916 - 1922 Luc MONTERET TIMBRES-MONNAIE A MADAGASCAR Novembre1 2020 EMERGENCY NOTES During the war of 14-18, current transactions suffered from the shortage of divisional money. The noble metal (silver) was hoarded and the non-ferrous metals reserved for weaponry. 50 centimes banknote issued in 1916 by the In metropolitan France, municipalities or chambers of commerce were Deux-Sèvres Chamber of authorized to issue emergency notes of low value, secured by equivalent Commerce (Sower on deposits in the bank, the left, chamois leather This had already been done during periods of crisis after the defeat of 1870 tanner on the right). Banknote of 50 centimes issued by the Municipal Council of Roubaix on November 8, 1871 (approved by the Prefect). or during the French Revolution. 15 Sols trust note issued in 1791 by the Caisse Patriotique de la ville de Saint-Maixent (Deux- Sèvres) on the back of a playing card (queen of diamonds). Luc MONTERET TIMBRES-MONNAIE DE MADAGASCAR 14 novembre 2020 2 COINAGE STAMPS A Decision of September 12, 1916 of the Governor General of Madagascar Hubert GARBIT authorized postmen to put into circulation postage stamps intended to compensate for the lack of divisional currency. It was not the first time that coinage stamps were used, the invention going to the American John Gault who in 1862, during the American Civil War, proposed to stick a stamp on a strong cardboard or insert in a copper capsule closed by a sheet of mica. Of course, the back had an advertisement! Images captured on the website de l’Association Philatélique Senlisienne The stamps will be used later in other colonies such as Guinea or the Ivory Coast.