Victor Schoelcher's Views on Race and Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

Fonds La Martinière

Cote PA-AP Nom Prénom Article Titre Contenu Dates extrêmes 189 HANOTAUX Gabriel 1 NOTES ET SOUVENIRS - Documents personnels et littéraires : 1876- 1908 - Fol. 2-10 - Notes sur le ministère Jules Simon ; 1876-1877. - Fol. 11-12 - Fragments de journal ; 1882-1887. - Fol. 23-64 - Journal ; Juin 1887-16 Mars 1894. - Fol. 65-69 - "Réflexions sur la vie politique" ; 20 Février 1892. - Fol. 70-113 - Notes et discours sur Jules Ferry ; 1893. - Fol. 114-118 - Articles de journaux sur Gabriel Hanotaux ; Juin 1894. - Fol. 119-172 - Notes et anecdotes rassemblées pour la rédaction de "l'Histoire contemporaine" ; 1901-1908. - Fol. 173-179 - Jugements esthétiques (sur Millet, Boldini, Manet ...) ; sans date. - Fol. 180-183 - Bons mots et anecdotes. - Fol. 184-195 - Notes de lectures, plans d'ouvrages. mardi 23 octobre 2007 MAE Fonds PA-AP Page 1 sur 34 Cote PA-AP Nom Prénom Article Titre Contenu Dates extrêmes 189 HANOTAUX Gabriel 2 NOTES ET SOUVENIRS - Notes d'audience du ministre etc ... (Orig. Aut.) : 213 1895- 1898 folios : - Fol. 2-13 - Entretiens avec le prince Lobanoff ; 1895. - Fol. 14-20 - Directives à Paul Cambon à Constantinople ; Juin 1896. - Fol. 21-28 - Note sur la politique étrangère de la France adressé à Félix Faure, à propos du voyage du tsar à Paris ; Septembre 1896-(?). - Fol. 29-37 - Conversations avec Chichkine ; 2 et 14 Octobre 1896. - Fol. 38-58 - Entretiens avec Nicolas II ; 12 Octobre 1896. - Fol. 59-65 - Conversations avec lord Dufferin ; 12 Octobre 1896. - Fol. 66-76 - Deuxième et troisième entretiens avec Chichkine ; 14 Octobre 1896. - Fol. 77-88 - "Projet pour mes conversations avec le comte Mouravieff" ; 26 Janvier 1897. -

Frederick Douglass

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph. D. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Zbe Hmcrican Crisis Biographies Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph.D. With the counsel and advice of Professor John B. McMaster, of the University of Pennsylvania. Each I2mo, cloth, with frontispiece portrait. Price $1.25 net; by mail» $i-37- These biographies will constitute a complete and comprehensive history of the great American sectional struggle in the form of readable and authoritative biography. The editor has enlisted the co-operation of many competent writers, as will be noted from the list given below. An interesting feature of the undertaking is that the series is to be im- partial, Southern writers having been assigned to Southern subjects and Northern writers to Northern subjects, but all will belong to the younger generation of writers, thus assuring freedom from any suspicion of war- time prejudice. The Civil War will not be treated as a rebellion, but as the great event in the history of our nation, which, after forty years, it is now clearly recognized to have been. Now ready: Abraham Lincoln. By ELLIS PAXSON OBERHOLTZER. Thomas H. Benton. By JOSEPH M. ROGERS. David G. Farragut. By JOHN R. SPEARS. William T. Sherman. By EDWARD ROBINS. Frederick Douglass. By BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Judah P. Benjamin. By FIERCE BUTLER. In preparation: John C. Calhoun. By GAILLARD HUNT. Daniel Webster. By PROF. C. H. VAN TYNE. Alexander H. Stephens. BY LOUIS PENDLETON. John Quincy Adams. -

Edward Bliss Emerson the Caribbean Journal And

EDWARD BLISS EMERSON THE CARIBBEAN JOURNAL AND LETTERS, 1831-1834 Edited by José G. Rigau-Pérez Expanded, annotated transcription of manuscripts Am 1280.235 (349) and Am 1280.235 (333) (selected pages) at Houghton Library, Harvard University, and letters to the family, at Houghton Library and the Emerson Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society. 17 August 2013 2 © Selection, presentation, notes and commentary, José G. Rigau Pérez, 2013 José G. Rigau-Pérez is a physician, epidemiologist and historian located in San Juan, Puerto Rico. A graduate of the University of Puerto Rico, Harvard Medical School and Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, he has written articles on public health, infectious diseases, and the history of medicine. 3 CONTENTS EDITOR'S NOTE .................................................................................................................................. 5 1. 'Ninety years afterward': The journal's discovery ....................................................................... 5 2. Previous publication of the texts .................................................................................................. 6 3. Textual genealogy: Ninety years after 'Ninety years afterward' ................................................ 7 a. Original manuscripts of the journal ......................................................................................... 7 b. Transcription history ................................................................................................................. -

A Cape of Asia: Essays on European History

A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 1 a cape of asia A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 2 A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 3 A Cape of Asia essays on european history Henk Wesseling leiden university press A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 4 Cover design and lay-out: Sander Pinkse Boekproductie, Amsterdam isbn 978 90 8728 128 1 e-isbn 978 94 0060 0461 nur 680 / 686 © H. Wesseling / Leiden University Press, 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 5 Europe is a small cape of Asia paul valéry A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 6 For Arnold Burgen A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 7 Contents Preface and Introduction 9 europe and the wider world Globalization: A Historical Perspective 17 Rich and Poor: Early and Later 23 The Expansion of Europe and the Development of Science and Technology 28 Imperialism 35 Changing Views on Empire and Imperialism 46 Some Reflections on the History of the Partition -

Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: a Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1993 Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons John Patrick Fitzgibbons Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgibbons, John Patrick, "Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons" (1993). Dissertations. 3283. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3283 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1993 John Patrick Fitzgibbons Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons by John Patrick Fitzgibbons, S.J. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chicago, Illinois May, 1993 Copyright, '°1993, John Patrick Fitzgibbons, S.J. All rights reserved. PREFACE Theodore Parker (1810-1860) fashioned a strategy of "man-making" and an ideology of manhood in response to the marginalization of the professional ministry in general and his own ministry in particular. Much has been written about Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and his abandonment of the professional ministry for a literary career after 1832. Little, however, has been written about Parker's deliberate choice to remain in the ministry despite formidable opposition from within the ranks of Boston's liberal clergy. -

The Madagascar Affair, Part 2

Imperial Disposition The Impact of Ideology on French Colonial Policy in Madagascar 1883-1896 Tucker Stuart Fross Mentored by Aviel Roshwald Advised by Howard Spendelow Senior Honors Seminar HIST 408-409 May 7, 2012 Table of Contents I. Introduction 2 II. The First Madagascar Affair, 1883-1885 25 III. Le parti colonial & the victory of Expansionist thought, 1885-1893 42 IV. The Second Madagascar Affair, part 1. Tension & Negotiation, 1894-1895 56 V. The Second Madagascar Affair, part 2. Expedition & Annexation, 1895-1896 85 VI. Conclusion 116 1 Chapter I. Introduction “An irresistible movement is bearing the great nations of Europe towards the conquest of fresh territories. It is like a huge steeplechase into the unknown.”1 --Jules Ferry Empires share little with cathedrals. The old cities built cathedrals over generations. Sons placed bricks over those laid down by their fathers. These were the projects of a town, a people, or a nation. The design was composed by an architect who would not live to see its completion, carried through generations in the memory of a collective mind, and patiently imposed upon the world. Empires may be the constructions of generations, but they do not often appear to result from the persistent projection of a unified design. Yet both empires and cathedrals have inspired religious devotion. In the late nineteenth century, the idea of empire took on the appearance of a transnational cult. Expansion of imperial control was deemed intrinsically valuable, not only as a means to power, but for the mere expression and propagation of the civilization of the conqueror. -

GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 by CLAUDIA MAREIKE

ROMANTICISM, ORIENTALISM, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 By CLAUDIA MAREIKE KATRIN SCHWABE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Claudia Mareike Katrin Schwabe 2 To my beloved parents Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisory committee chair, Dr. Barbara Mennel, who supported this project with great encouragement, enthusiasm, guidance, solidarity, and outstanding academic scholarship. I am particularly grateful for her dedication and tireless efforts in editing my chapters during the various phases of this dissertation. I could not have asked for a better, more genuine mentor. I also want to express my gratitude to the other committee members, Dr. Will Hasty, Dr. Franz Futterknecht, and Dr. John Cech, for their thoughtful comments and suggestions, invaluable feedback, and for offering me new perspectives. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the abundant support and inspiration of my friends and colleagues Anna Rutz, Tim Fangmeyer, and Dr. Keith Bullivant. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my family, particularly my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe, as well as to my brother Marius and his wife Marina Schwabe. Many thanks also to my dear friends for all their love and their emotional support throughout the years: Silke Noll, Alice Mantey, Lea Hüllen, and Tina Dolge. In addition, Paul and Deborah Watford deserve special mentioning who so graciously and welcomingly invited me into their home and family. Final thanks go to Stephen Geist and his parents who believed in me from the very start. -

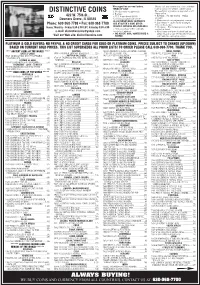

Distinctive Coins |

We suggest fax or e-mail orders. Please call and reserve the coins, and then TERMS OF SALE mail or fax us the written confirmation. DISTINCTIVE COINS 1. No discounts or approvals. We need your signature of approval on all 2. Postage: charge sales. 422 W. 75th St., a. U.S. insured mail $5.00. 4. Returns – for any reason – within b. Overseas registered $20.00. 21 days. Downers Grove, IL 60516 5. Minors need written parental consent. ALL INTERNATIONAL SHIPMENTS 6. Lay Aways – can be easily arranged. Phone: 630-968-7700 • Fax: 630-968-7780 ARE AT BUYER’S RISK! OTHER Give us the terms. Hours: Monday - Friday 9:30-5:00 CST; Saturday 9:30-3:00 INSURED SERVICES ARE AVAILABLE. 7. Overseas – Pro Forma invoice will be c. Others such as U.P.S. or FedEx mailed or faxed. e-mail: [email protected] need street address. 8. Most items are one-of-a-kind and are 3. WE ACCEPT VISA, MASTERCARD & subject to prior sale. Distinctive Coins is Visit our Web site: distinctivecoins.com PAYPAL! not liable for cataloging errors. PLATINUM & GOLD BUYERS: NO PAYPAL & NO CREDIT CARDS FOR GOLD OR PLATINUM COINS. PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE (UP/DOWN) BASED ON CURRENT GOLD PRICES. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL PRIOR LISTS! TO ORDER PLEASE CALL 630-968-7700. THANK YOU. **** ANCIENT COINS OF THE WORLD **** AUSTRIA 1891A 5 FRANCOS K-12 NGC-AU DETAILS CLEANED INDIA, MEWAR GREECE-CHIOS 1908 5 CORONA K-2809 NGC-MS63 60TH .............225 1 YR TYPE PLEASANT TONE .................................380 1928 RUPEE Y-22.2 NGC-MS64 THICK ...................110 (1421-36) DUCAT NGC-MS61 -

American Liberal Pacifists and the Memory of Abolitionism, 1914-1933 Joseph Kip Kosek

American Liberal Pacifists and the Memory of Abolitionism, 1914-1933 Joseph Kip Kosek Americans’ memory of their Civil War has always been more than idle reminiscence. David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory is the best new work to examine the way that the nation actively reimagined the past in order to explain and justify the present. Interdisciplinary in its methods, ecumenical in its sources, and nuanced in its interpretations, Race and Reunion explains how the recollection of the Civil War became a case of race versus reunion in the half-century after Gettysburg. On one hand, Frederick Douglass and his allies promoted an “emancipationist” vision that drew attention to the role of slavery in the conflict and that highlighted the continuing problem of racial inequality. Opposed to this stance was the “reconciliationist” ideal, which located the meaning of the war in notions of abstract heroism and devotion by North and South alike, divorced from any particular allegiance. On this ground the former combatants could meet undisturbed by the problems of politics and ideological difference. This latter view became the dominant memory, and, involving as it did a kind of forgetting, laid the groundwork for decades of racial violence and segregation, Blight argues. Thus did memory frame the possibilities of politics and moral action. The first photograph in Race and Reunion illustrates this victory of reunion, showing Woodrow Wilson at Gettysburg in 1913. Wilson, surrounded by white veterans from North and South, with Union and Confederate flags flying, is making a speech in which he praises the heroism of the combatants in the Civil War while declaring their “quarrel forgotten.” The last photograph in Blight’s book, though, invokes a different story about Civil War memory. -

An Important Collection of French Coins

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AN IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF FRENCH COINS Essais and Piedforts 2001 Republic, Copper Essai Monneron Monnaie de Confiance 2-Sols, Year 1, 1792, by Dupré, Hercules kneeling breaking royal sceptre, owl behind, rev pyramid, plain edge, 15.40g, 32mm (as VG 342, but plain edge; Maz 332a; Reynaud 8a). Extremely fine. £150-200 2002 Louis Philippe (1830-1848), Bronze Essai 3-Centimes and 2-Centimes, undated (1831-1842), by Domard, first with -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I 75-3032

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.