Biodiversity Audit and Tolerance Sensitivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring of Odonata in Britain and Possible Insights Into Climate Change

A peer-reviewed open-access journal BioRisk 5: 127–139Monitoring (2010) of Odonata in Britain and possible insights into climate change 127 doi: 10.3897/biorisk.5.846 RESEARCH ARTICLE BioRisk http://biorisk-journal.com/ Monitoring of Odonata in Britain and possible insights into climate change Adrian J. Parr 10 Orchard Way, Barrow, Bury St Edmunds, Suff olk IP29 5BX, Great Britain Corresponding author: Adrian J. Parr ([email protected]) Academic editor: Jürgen Ott | Received 29 July 2010 | Accepted 20 August 2010 | Published 30 December 2010 Citation: Parr AJ (2010) Monitoring of Odonata in Britain and possible insights into climate change. In: Ott J (Ed) (2010) Monitoring Climatic Change With Dragonfl ies. BioRisk 5: 127–139. doi: 10.3897/biorisk.5.846 Abstract Th e history of recording and monitoring of Odonata in Britain is briefl y described. Results are then pre- sented which suggest that the country’s Odonata fauna is currently in a period of fl ux, in a manner consist- ent with the actions of a high-level regulatory factor such as climate change. Th e ranges of many resident species are shifting. Leucorrhinia dubia has recently been lost from southern England, but many species are presently expanding their ranges to the north and west, some (such as Aeshna mixta and Anax imperator) with considerable speed. In addition to these changes, a number of ‘southern’ species have started to ap- pear in Britain for the very fi rst time. Th ese include Lestes barbarus, Erythromma viridulum (which has now become a locally-common resident in southeast England), Anax parthenope and Crocothemis erythraea. -

QQR 7 Information Pack

7th Quinquennial Review of Schedules 5 and 8 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981) Information Pack (version 2.21) 14 May 2021 1 Version 2.2: Four reptiles and two seals removed from the EPS list (Annex 1); one EPS amphibian and two EPS reptiles that are all Endangered removed from Annex 2 – these species were included in Version 2 and/or 2.1 in error. See Annex 1 and Annex 2 for further information. 1. Introduction Every five years, the country nature conservation bodies (Natural England, Natural Resources Wales and NatureScot), working jointly through the UK Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), review Schedules 5 and 8 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (WCA) 1981. The review will provide recommendations to the Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and to Ministers for the Environment in the Scottish Government and Welsh Government for changes to these schedules2. This is known as the Quinquennial Review (QQR). As part of the QQR, stakeholders are provided with the opportunity to propose changes to the species on the schedules. This Information Pack has been produced for the 7th QQR (QQR 7). It is important to note that this QQR differs from previous ones. The Information Pack explains the new selection criteria, provides a timetable, and explains the process to be used by stakeholders. Contact details of the QQR Inter-agency Group who are managing QQR 7, are listed in Section 5. In addition, the Information Pack provides details of how to complete the online survey through which stakeholders propose new species for inclusion on, or removal of existing species from Schedules 5 and 8, or propose a change to how species are protected on the schedules. -

The Magazine of the British Dragonfly Society Spring 2013 Favourite Days 30Th Anniversary Stamp Issue

Dragonfly 63 NewsThe Magazine of the British Dragonfly Society Spring 2013 www.british-dragonflies.org.uk Favourite Days 30th Anniversary stamp issue Observations On the Trail of the Orange-spotted Emerald Dragonfly News 63 The Magazine of the British Dragonfly Society Published twice a year, in April and October, Dragonfly News covers all aspects of the British Dragonfly Society’s field, recording, monitoring, research, conservation and social activities, as well as information from the wider dragonfly, natural history and conservation world. The emphasis is on dragonflies recorded in the UK. *The British Dragonfly Society aims to promote and encourage the study, conservation and understanding of dragonflies and their natural habitats, especially in the UK, and to raise public awareness of dragonflies. Dragonfly News is edited & designed by: Trustees & Officers of the BDS Mark Tyrrell, 8 Warwick Close, Raunds, Chairman: Pam Taylor, Decoy Farm, Decoy Road, Potter Northants., NN9 6JH Tel. Heigham, Norfolk, NR29 5LX. Tel. e-mail: Vice-Chairman: Vacant Deadlines for inclusion of copy: Secretary: Henry Curry, 23 Bowker Way, Whittlesey, Spring 31 January Peterborough, PE7 1PY. Tel. Autumn 31 July Treasurer: Brian Walker, 49 Roman Way, Wantage, Advertising Rates: Oxfordshire, OX12 9YF. Tel. £15 for small-ad (text only); £40 for quarter- Trustees: Andy Harmer, Alan Nelson, *Mick Parfitt. page; £60 for half-page; £100 for full-page. Journal Editor: Peter Mill, 8 Cookridge Grove, LEEDS, LS16 7LH. © British Dragonfly Society 2013 Shop Manager: Lynn Curry, 23 Bowker Way, Whittlesey, All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Peterborough, PE7 1PY Tel. reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of the British Dragonfly Conservation Group (DCG) Dragonfly Society or the copyright owner. -

Dragonfly News 66

Dragonfly News 66 The Magazine of the British Dragonfly Society Autumn 2014 www.british-dragonflies.org.uk Meet the new BDS Chairman, How many Willow Emeralds are David Chelmick ovipositing? Dragonfly hunting....in Sweden? Andy Holt’s unique larval portraits How tatty can a dragonfly be and still fly? Dragonfly News 66 The Magazine of the British Dragonfly Society Published twice a year, in April and October, Dragonfly News covers all aspects of the British Dragonfly Society’s field, recording, monitoring, research, conservation and social activities, as well as information from the wider dragonfly, natural history and conservation world. The emphasis is on dragonflies recorded in the UK. The British Dragonfly Society aims to promote and encourage the study, conservation and understanding of dragonflies and their natural habitats, especially in the UK, and to raise public awareness of dragonflies. Dragonfly News is edited & designed by: Trustees & Officers of the BDS Mark Tyrrell, 8 Warwick Close, Raunds, Chairman: David Chelmick Northants., NN9 6JH Tel. Vice-Chairman: Vacant e-mail: Secretary: Henry Curry, 23 Bowker Way, Whittlesey, Peterborough, PE7 1PY. Tel. Deadlines for inclusion of copy: Spring 31 January Treasurer: Brian Walker, 49 Roman Way, Wantage, Autumn 31 July Oxfordshire, OX12 9YF. Tel. Advertising Rates: Trustees: David Goddard, Stuart Irons, Mick Parfitt. £15 for small-ad (text only); £40 for quarter- Journal Editor: Peter Mill, 8 Cookridge Grove, LEEDS, page; £60 for half-page; £100 for full-page. LS16 7LH. Shop Manager: Lynn Curry, 23 Bowker Way, Whittlesey, Peterborough, PE7 1PY Tel. © British Dragonfly Society 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any Dragonfly Conservation Group (DCG) form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, Convenor: Dave Smallshire, 8, Twindle Beer, Chudleigh, Newton recording or otherwise, without the permission of the British Abbot, Devon, TQ13 0JP. -

196 Arachnology (2019)18 (3), 196–212 a Revised Checklist of the Spiders of Great Britain Methods and Ireland Selection Criteria and Lists

196 Arachnology (2019)18 (3), 196–212 A revised checklist of the spiders of Great Britain Methods and Ireland Selection criteria and lists Alastair Lavery The checklist has two main sections; List A contains all Burach, Carnbo, species proved or suspected to be established and List B Kinross, KY13 0NX species recorded only in specific circumstances. email: [email protected] The criterion for inclusion in list A is evidence that self- sustaining populations of the species are established within Great Britain and Ireland. This is taken to include records Abstract from the same site over a number of years or from a number A revised checklist of spider species found in Great Britain and of sites. Species not recorded after 1919, one hundred years Ireland is presented together with their national distributions, before the publication of this list, are not included, though national and international conservation statuses and syn- this has not been applied strictly for Irish species because of onymies. The list allows users to access the sources most often substantially lower recording levels. used in studying spiders on the archipelago. The list does not differentiate between species naturally Keywords: Araneae • Europe occurring and those that have established with human assis- tance; in practice this can be very difficult to determine. Introduction List A: species established in natural or semi-natural A checklist can have multiple purposes. Its primary pur- habitats pose is to provide an up-to-date list of the species found in the geographical area and, as in this case, to major divisions The main species list, List A1, includes all species found within that area. -

A Revision of the New World Plant-Mining Moths of the Family

Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 625 A Revision of the New World Plant-Mining Moths of the Family (Lepidoptera: Nepticuloidea) Donald R. Davis and Jonas R. Stonis SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com- mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions in History and Technology Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Smithsonian Contributions in Visual and Material Culture Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology In these series, the Institution pubHshes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaus. The Contributions Series are distributed by mailing lists to Ubraries, universities, and similar institutions through- out the world. Manuscripts submitted for series publication are received by the Smith- sonian Institution Scholarly Press from authors with direct affiliation with the various Smithsonian museums or bureaus and are subject to peer review and review for compliance with manuscript preparation guidelines. -

Dragonflies - 2003

DRAGONFLIES - 2003 Banded Demoiselle Calopteryx splendens More commonly recorded along streams and rivers but small numbers are now regularly seen along the canal since the first on July 6, 1987. The only record away from the canal was at Fly Pool on August 20 1993. Emerald Damselfly Lestes sponsa This is a common species especially where there is emergent vegetation amongst which it is well camouflaged. Most frequent from July to August. Large Red Damselfly Pyrrhosoma nymphula Frequently the first species to be recorded in the spring. Small numbers can be found at most sites usually from mid-May to early August. Red-eyed Damselfly Erythromma najas A regionally scarce species that is locally common during June and July on the canals of the Brownhills and Pelsall area and at Marklew’s Pond on Brownhills Common. It has been recorded once at Chasewater on the Nine Foot Pool. Azure Damselfly Coenagrion puella A fairly common species mainly recorded from the well vegetated smaller pools from late May to the end of July. Common Blue Damselfly Enallagma cyathigerum Probably the most abundant species and it can often be seen flying low over open water from late May to early September. Blue-tailed Damselfly Ischnura elegans A very common species to be found in good numbers from late May to the end of August. Colour variant females are occasionally noted. Common Hawker Aeshna juncea Essentially a heathland species that can usually be seen around the North Marsh and the Eastern Heath in August and September. Migrant Hawker Aeshna mixta A relatively recent coloniser of South Staffordshire with Chasewater’s first record being on September 27, 1990. -

Microlepidoptera in Nederland, Vooral in 2007-2010 Met Een Terugblik Op 30 Jaar Faunistisch Onderzoek

entomologische berichten 91 73 (3) 2013 Microlepidoptera in Nederland, vooral in 2007-2010 met een terugblik op 30 jaar faunistisch onderzoek K. J. (Hans) Huisman J. C. (Sjaak) Koster Tymo S.T. Muus Erik J. van Nieukerken TREFWOORDEN Faunistiek, nieuwe waarneming, provincies, areaaluitbreidingen Entomologische Berichten 73 (3): 91-117 In de jaren 2007-2010 werden maar liefst elf soorten kleine vlinders nieuw voor onze fauna gevonden: Infurcitinea teriolella, Bucculatrix ulmifoliae, Caloptilia fidella, Phyllonorycter issikii, Coleophora motacillella, Cochylis molliculana, Cnephasia sedana, Clepsis dumicolana, Lobesia botrana, Pseudococcyx tessulatana en Evergestis aenealis. Daarnaast werden drie soorten al elders gemeld: Caloptilia hemidactylella, Cydalima perspectalis en Bucculatrix ainsliella. Na 30 jaar van jaarlijsten geven we een evaluatie, met onder andere een totaal van 128 nieuw gemelde soorten. Dit zijn er minder dan in Denemarken, maar meer dan op de Britse Eilanden of in Zweden. We verklaren deze verschillen door het verschil in oppervlak van de landen: hoe kleiner het land, hoe meer kans dat er nieuwe soorten gevonden worden. Dit jaaroverzicht is het laatste dat in deze vorm verschijnt. Dit is het negentiende jaaroverzicht van de Nederlandse Micro- die beoordeeld konden worden door specialisten. We hopen dat lepidoptera sedert 1983. Een index van alle overzichten tot 2000 we een goed evenwicht gevonden hebben in het spanningsveld werd gegeven door Koster & Van Nieukerken (2003). tussen volledigheid en betrouwbaarheid. De jaren 2007–2010 waren wederom aan de warme kant met Door de snelle berichtgeving op internet wordt het voor het uitzondering van 2010, dat sinds 1996 het eerste jaar was met samenstellen van een gedrukte ‘jaarlijst’ steeds moeilijker om een temperatuur beneden het langjarige gemiddelde van 9,8°C voldoende actueel te blijven en toch de grens van een bepaald (jaargemiddelden 2007-2010 11,2; 10,6; 10,5; 9,1°C). -

Cambridgeshire & Essex Butterfly Conservation

Butterfly Conservation Regional Action Plan For Anglia (Cambridgeshire, Essex, Suffolk & Norfolk) This action plan was produced in response to the Action for Butterflies project funded by WWF, EN, SNH and CCW This regional project has been supported by Action for Biodiversity Cambridgeshire and Essex Branch Suffolk branch BC Norfolk branch BC Acknowledgements The Cambridgeshire and Essex branch, Norfolk branch and Suffolk branch constitute Butterfly Conservation’s Anglia region. This regional plan has been compiled from individual branch plans which are initially drawn up from 1997-1999. As the majority of the information included in this action plan has been directly lifted from these original plans, credit for this material should go to the authors of these reports. They were John Dawson (Cambridgeshire & Essex Plan, 1997), James Mann and Tony Prichard (Suffolk Plan, 1998), and Jane Harris (Norfolk Plan, 1999). County butterfly updates have largely been provided by Iris Newbery and Dr Val Perrin (Cambridgeshire and Essex), Roland Rogers and Brian Mcllwrath (Norfolk) and Richard Stewart (Suffolk). Some of the moth information included in the plan has been provided by Dr Paul Waring, David Green and Mark Parsons (BC Moth Conservation Officers) with additional county moth data obtained from John Dawson (Cambridgeshire), Brian Goodey and Robin Field (Essex), Barry Dickerson (Huntingdon Moth and Butterfly Group), Michael Hall and Ken Saul (Norfolk Moth Survey) and Tony Prichard (Suffolk Moth Group). Some of the micro-moth information included in the plan was kindly provided by A. M. Emmet. Other individuals targeted with specific requests include Graham Bailey (BC Cambs. & Essex), Ruth Edwards, Dr Chris Gibson (EN), Dr Andrew Pullin (Birmingham University), Estella Roberts (BC, Assistant Conservation Officer, Wareham), Matthew Shardlow (RSPB) and Ken Ulrich (BC Cambs. -

Index to Contents

Index to Contents Author(s) Title Year Vol Pages Holland, Sonia Dragonfly Survey Reports – 1. Gloucestershire 1983 1 (1) 1-3 Butler, Stephen Notes on finding larvae of Somatochlora arctica (Zetterstedt) in N. W. Scotland 1983 1 (1) 4-5 Winsland, David Some observations on Erythromma najas (Hansemann) 1983 1 (1) 6 Merritt, R. Is Sympetrum nigrescens Lucas a good species? 1983 1 (1) 7-8 Vick, G. S. Is Sympetrum nigrescens Lucas a good species? 1983 1 (1) 7-8 Merritt, R. Coenagrion mercuriale (Charpentier) with notes on habitat 1983 1 (1) 9-12 Chelmick, D. G. Observations on the ecology and distribution of Oxygastra curtisii (Dale) 1983 1 (2) 11-14 Khan, R. J. Observations of Wood-mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) and Hobby (Falco subbuteo) feeding on dragonflies 1983 1 (2) 15 Marren, P. R. Scarce Species Status Report 2. A review of Coenagrion hastulatum (Charpentier) in Britain 1983 1 (2) 16-19 Merritt, R. Is Sympetrum nigrescens Lucas a good species? 1983 1 (2) 16-19 Mayo, M. C. A. Coenagrion mercuriale (Charpentier) on the flood plains of the River Itchen and River Test in Hampshire 1983 1 (2) 20-21 Welstead, A. R. Coenagrion mercuriale (Charpentier) on the flood plains of the River Itchen and river Test in Hampshire 1983 1 (2) 20-21 Kemp, R. G. Notes and observations on Gomphus vulgatissimus (Linnaeus) on the river Severn and River Thames 1983 1 (2) 22-25 Vick, G. S. Notes and observations on Gomphus vulgatissimus (Linnaeus) on the river Severn and River Thames 1983 1 (2) 22-25 Corbet, P. -

PLANTER TIL MINIVÅDOMRÅDER Videnskabelig Rapport Fra DCE – Nationalt Center for Miljø Og Energi Nr

PLANTER TIL MINIVÅDOMRÅDER Videnskabelig rapport fra DCE – Nationalt Center for Miljø og Energi nr. 334 2019 AARHUS AU UNIVERSITET DCE – NATIONALT CENTER FOR MILJØ OG ENERGI [Tom side] PLANTER TIL MINIVÅDOMRÅDER Videnskabelig rapport fra DCE – Nationalt Center for Miljø og Energi nr. 334 2019 Beate Strandberg Annica Olesen Kirstine Thiemer Lars Skipper Kevin Kuhlmann Clausen Niels Kanstrup Tenna Riis Aarhus Universitet, Institut for Bioscience AARHUS AU UNIVERSITET DCE – NATIONALT CENTER FOR MILJØ OG ENERGI Datablad Serietitel og nummer: Videnskabelig rapport fra DCE - Nationalt Center for Miljø og Energi nr. 334 Titel: Planter til minivådområder Forfattere: Beate Strandberg, Annica Olesen, Kirstine Thiemer, Lars Skipper, Kevin Kuhlmann Clausen, Niels Kanstrup & Tenna Riis Institution: Aarhus Universitet, Institut for Bioscience Udgiver: Aarhus Universitet, DCE – Nationalt Center for Miljø og Energi © URL: http://dce.au.dk Udgivelsesår: September 2019 Redaktion afsluttet: Juli 2019 Faglig kommentering: Carl Christian Hoffmann og Torben Linding Lauridsen Kvalitetssikring, DCE: Signe Jung-Madsen Finansiel støtte: Grønt Udviklings- og DemonstrationsProgram (GUDP), Landbrugsstyrelsen Bedes citeret: Strandberg, B., Olesen, A., Thiemer, K., Skipper, L., Clausen, K.K., Kanstrup, N. & Riis, T. 2019. Planter til minivådområder. Aarhus Universitet, DCE – Nationalt Center for Miljø og Energi, 138 s. - Videnskabelig rapport nr. 334 http://dce2.au.dk/pub/SR334.pdf Gengivelse tilladt med tydelig kildeangivelse Sammenfatning: Ved etablering af bl.a. minivådområder anbefales at de lavvande dele af anlæggene beplantes. Sædvanligvis benyttes meget få plantearter, primært tagrør, til beplantningen. Ud over tagrør er der en del andre planter, som kan benyttes til beplantningen. Plantekataloget præsenterer 82 plantearter, der alle vil kunne benyttes. I præsentationen af arterne er hovedvægten lagt på den primære opgave, som planterne skal bidrage til, nemlig næringsstoffjernelse, men en del andre økosystemfunktioner, som planterne kan bidrage til, er også medtaget. -

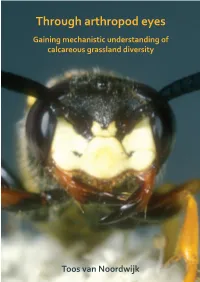

Through Arthropod Eyes Gaining Mechanistic Understanding of Calcareous Grassland Diversity

Through arthropod eyes Gaining mechanistic understanding of calcareous grassland diversity Toos van Noordwijk Through arthropod eyes Gaining mechanistic understanding of calcareous grassland diversity Van Noordwijk, C.G.E. 2014. Through arthropod eyes. Gaining mechanistic understanding of calcareous grassland diversity. Ph.D. thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Keywords: Biodiversity, chalk grassland, dispersal tactics, conservation management, ecosystem restoration, fragmentation, grazing, insect conservation, life‑history strategies, traits. ©2014, C.G.E. van Noordwijk ISBN: 978‑90‑77522‑06‑6 Printed by: Gildeprint ‑ Enschede Lay‑out: A.M. Antheunisse Cover photos: Aart Noordam (Bijenwolf, Philanthus triangulum) Toos van Noordwijk (Laamhei) The research presented in this thesis was financially spupported by and carried out at: 1) Bargerveen Foundation, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; 2) Department of Animal Ecology and Ecophysiology, Institute for Water and Wetland Research, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands; 3) Terrestrial Ecology Unit, Ghent University, Belgium. The research was in part commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation as part of the O+BN program (Development and Management of Nature Quality). Financial support from Radboud University for printing this thesis is gratefully acknowledged. Through arthropod eyes Gaining mechanistic understanding of calcareous grassland diversity Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. mr. S.C.J.J. Kortmann volgens besluit van het college van decanen en ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor in de biologie aan de Universiteit Gent op gezag van de rector prof. dr. Anne De Paepe, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 26 augustus 2014 om 10.30 uur precies door Catharina Gesina Elisabeth van Noordwijk geboren op 9 februari 1981 te Smithtown, USA Promotoren: Prof.