Social Structure and Behaviour of the Manta Ray (Manta Birostris)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manta Birostris) in CMS Appendix I & II, As Proposed by the Government of Ecuador (I/5)

SHARK ADVOCATES INTERNATIONAL Support Inclusion of the Giant Manta Ray (Manta birostris) in CMS Appendix I & II, as proposed by the Government of Ecuador (I/5) Overview Mantas, exceptionally large and vulnerable rays found around the world in tropical to temperate waters, are under increasing threat. Critical aggregation areas are at risk while new markets for manta gills drive unsustainable fisheries that may squander substantial economic benefits of manta-based tourism. Some countries have protected manta rays, but additional national safeguards, as well as collaborative regional efforts to study and conserve manta rays, are urgently needed to avoid further depletion of these valuable and iconic animals. The Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) is an ideal vehicle for facilitating conservation of manta rays and their essential habitats. JACKIE REID / NOAA Biological Characteristics and harpoons. Their large size and tendency to move slowly The giant (Manta birostris) and reef (Manta alfredi) manta in predictable aggregations make them easy targets. rays are among the world’s largest fishes. The giant manta ray can grow to more than seven meters across. Manta rays Manta rays are used for human consumption and shark bait, are especially vulnerable to overexploitation due to their very and are increasingly sought for their gill rakers, which are limited reproductive capacity. Female mantas are thought to traded to East Asia for use in Chinese medicine. This relatively mature at 8-10 years of age, produce just one pup after a new market is driving dramatic increases in targeted manta year-long gestation period (with a year or two resting stage), fisheries, particularly in Southeast Asia, India, and Eastern and live at least 30 years. -

Living Systems

K2 -3 Lesson Plan Living Systems Why not get a hands on experience with your students at Irukandji Shark and Ray Encounters to learn about the oceans ecosystems from Apex Predators to Primary producers. This Lesson plan is designed for students to observe and study the marine environment through interactive educational talks on Elasmobranches Students will be able to Identify and describe the structure and function of living things Interact with the most misunderstood species in our marine systems Shark and Ray and their ecosystems. To observe marine animals and their reliance on all species . Students will look at the impacts on pollutants on marine plants by performing water test on controlled water source for a report. observe the food chain within a marine environment Observe various life cycles of Sharks and Rays. Identify, describe and evaluates the interactions between living things and their effects on the environment Look at Importance of Chondricthyan fishes (Sharks, Rays and Chimeras) to the marine environment and society, through an insightful look into 6 species life history strategies .to identify current conservation efforts of aquariums and marine parks throughout Australia. Irukandji Shark and Ray Encounters K2 -3 Lesson Plan Learning Environment Objectives Observe different elasmobranches Core component is Group Work observe marine animals and relationships Ray Lagoon Food chain within a marine environment Tawny Terrian interactions between living things Fiddler Flats Identify current conservation efforts of aquariums and marine parks throughout Australia. Materials Step 4: Getting wet Ray lagoon 25 minutes This is where students will get a hands on experience feeding, touching and interacting Pencil with elasmobranches and teleost within their Activity sheet environment Ruler and clip board Objectives Observe the different forms of structure Steps from plates to teeth. -

Chondrichthyan Fishes (Sharks, Skates, Rays) Announcements

Chondrichthyan Fishes (sharks, skates, rays) Announcements 1. Please review the syllabus for reading and lab information! 2. Please do the readings: for this week posted now. 3. Lab sections: 4. i) Dylan Wainwright, Thursday 2 - 4/5 pm ii) Kelsey Lucas, Friday 2 - 4/5 pm iii) Labs are in the Northwest Building basement (room B141) 4. Lab sections done: first lab this week on Thursday! 5. First lab reading: Agassiz fish story; lab will be a bit shorter 6. Office hours: we’ll set these later this week Please use the course web site: note the various modules Outline Lecture outline: -- Intro. to chondrichthyan phylogeny -- 6 key chondrichthyan defining traits (synapomorphies) -- 3 chondrichthyan behaviors -- Focus on several major groups and selected especially interesting ones 1) Holocephalans (chimaeras or ratfishes) 2) Elasmobranchii (sharks, skates, rays) 3) Batoids (skates, rays, and sawfish) 4) Sharks – several interesting groups Not remotely possible to discuss today all the interesting groups! Vertebrate tree – key ―fish‖ groups Today Chondrichthyan Fishes sharks Overview: 1. Mostly marine 2. ~ 1,200 species 518 species of sharks 650 species of rays 38 species of chimaeras Skates and rays 3. ~ 3 % of all ―fishes‖ 4. Internal skeleton made of cartilage 5. Three major groups 6. Tremendous diversity of behavior and structure and function Chimaeras Chondrichthyan Fishes: 6 key traits Synapomorphy 1: dentition; tooth replacement pattern • Teeth are not fused to jaws • New rows move up to replace old/lost teeth • Chondrichthyan teeth are -

Florida's Fintastic Sharks and Rays Lesson and Activity Packet

Florida's Fintastic Sharks and Rays An at-home lesson for grades 3-5 Produced by: This educational workbook was produced through the support of the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program. 1 What are sharks and rays? Believe it or not, they’re a type of fish! When you think “fish,” you probably picture a trout or tuna, but fishes come in all shapes and sizes. All fishes share the following key characteristics that classify them into this group: Fishes have the simplest of vertebrate hearts with only two chambers- one atrium and one ventricle. The spine in a fish runs down the middle of its back just like ours, making fish vertebrates. All fishes have skeletons, but not all fish skeletons are made out of bones. Some fishes have skeletons made out of cartilage, just like your nose and ears. Fishes are cold-blooded. Cold-blooded animals use their environment to warm up or cool down. Fins help fish swim. Fins come in pairs, like pectoral and pelvic fins or are singular, like caudal or anal fins. Later in this packet, we will look at the different types of fins that fishes have and some of the unique ways they are used. 2 Placoid Ctenoid Ganoid Cycloid Hard protective scales cover the skin of many fish species. Scales can act as “fingerprints” to help identify some fish species. There are several different scale types found in bony fishes, including cycloid (round), ganoid (rectangular or diamond), and ctenoid (scalloped). Cartilaginous fishes have dermal denticles (Placoid) that resemble tiny teeth on their skin. -

Lesser Devil Rays Mobula Cf. Hypostoma from Venezuela Are Almost Twice Their Previously Reported Maximum Size and May Be a New Sub-Species

Journal of Fish Biology (2017) 90, 1142–1148 doi:10.1111/jfb.13252, available online at wileyonlinelibrary.com Lesser devil rays Mobula cf. hypostoma from Venezuela are almost twice their previously reported maximum size and may be a new sub-species N. R. Ehemann*†‡§, L. V. González-González*† and A. W. Trites‖ *Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Apartado Postal 592, La Paz, Baja California Sur C.P. 23000, Mexico, †Escuela de Ciencias Aplicadas del Mar (ECAM), Boca del Río, Universidad de Oriente, Núcleo Nueva Esparta (UDONE), Boca del Río, Nueva Esparta, C.P. 06304, Venezuela, ‡Proyecto Iniciativa Batoideos (PROVITA), Caracas, Venezuela and ‖Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada (Received 8 September 2016, Accepted 23 November 2016) Three rays opportunistically obtained near Margarita Island, Venezuela, were identified as lesser devil rays Mobula cf. hypostoma, but their disc widths were between 207 and 230 cm, which is almost dou- ble the reported maximum disc width of 120 cm for this species. These morphometric data suggest that lesser devil rays are either larger than previously recognized or that these specimens belong to an unknown sub-species of Mobula in the Caribbean Sea. Better data are needed to describe the distribu- tion, phenotypic variation and population structure of this poorly known species. © 2017 The Fisheries Society of the British Isles Key words: batoids; by-catch; Caribbean Sea; Chondrichthyes; Myliobatiformes. There is limited biological and fisheries information about the body size at maturity, population size, stock, maximum age and length–mass relationships of Mobula hypos- toma (Bancroft, 1831), better known as the lesser devil ray. -

Marine Animals II

Marine Animals II. The Chordates OCN 201 Biology Lecture 7 Arthropods Segmented Worms The Animal Chordates Family Tree Mollusks Echinoderms Round Worms Cnidarians Ctenophores Flatworms Sponges Placozoa Ancestral Protist Chordate Tree Invertebrates Vertebrates Chordate Features Chordate Features Tunicates Salps • Pelagic or benthic • Often colonial • Suspension feeders Ascidians (sea squirts) Larvaceans Lancelets • Small fish-like, No Jaw • Suspension feeder • Can swim, but usually stays partly buried Amphioxus The Major Fish Groups • Jawless fishes (Agnatha) • Cartilaginous fishes (Chondrichthyes) • Bony fishes (Osteichthyes) Jawless Fish Lamprey (Parasite) • No jaws • No appendages • Cartilaginous • Parasites or Scavengers Hagfish (Scavenger) Jawless Fish Hagfish slime defense Cartilaginous Fish (Chondrichthyes) • Sharks, Skates and Rays • Skeleton of cartilage • Have jaws • Carnivores or Planktivores Cartilaginous Fish: Planktivores • Planktivores (filter feeders) are largest • Gaping mouth with small or no teeth • Gill rakers • Manta Ray (8 m across!) Gill Rakers • Whale Shark (up to 17 m long!) Planktivores Whale Shark Manta Ray Cartilaginous Fish: Carnivores Cookie-Cutter Shark Photo: NOAA Cookie-Cutter Shark Wounds Goblin Shark Photo: Mike Spalding vis WIRED magazine Bony Fish (Osteichtyes) • 22,000 species Stout Infantfish • From about <1 cm to 11 m • Surface to ≥ 8370 m deep Oarfish Herbivores Herbivores (algae) Planktivores (Filter Feeders) Anchovies H O Sardines 2 filter: gill rakers mouth gill opening gut Used by the most successful -

Seasonal Occurrences of Manta Birostris (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae) in Southeastern Brazil

Ichthyol Res DOI 10.1007/s10228-008-0060-3 SHORT REPORT Seasonal occurrences of Manta birostris (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae) in southeastern Brazil Osmar J. Luiz Jr Æ Ana Paula Balboni Æ Guilherme Kodja Æ Maurı´cio Andrade Æ Heloisa Marum Received: 25 July 2007 / Revised: 15 May 2008 / Accepted: 20 May 2008 Ó The Ichthyological Society of Japan 2008 Abstract An analysis of 79 underwater photographs of Notarbartolo-di-Sciara and Hillyer (1989) and Lobel Manta birostris gathered over a period of nine years in a (2003) reported patterns of seasonal occurrences at Vene- marine protected area in southeastern Brazil suggests a zuela (Southern Caribbean) and Johnston Atoll (Central high predictability of manta ray occurrences in the region Pacific). These authors infer that aggregations occur in during the austral winter (June–September). The reasons temporally and spatially predictable foraging grounds for this are probably related to the seasonal oceanographic where blooms of plankton arise. Seasonality in other large conditions, as characterized by the presence of a coastal planktivorous elasmobranches such basking sharks, whale front at the study site in winter and consequent plankton sharks and Mobula rays is often related to temporal vari- enrichment, which provides a feeding opportunity for ability in the abundance of their zooplankton prey manta rays. In addition, a melanistic individual in the (Notarbartolo-di-Sciara 1988; Taylor 1996; Sims et al. Atlantic Ocean that is similar in color to the Pacific 1997; Wilson et al. 2001). Ocean’s ‘‘black manta’’ is reported for the first time. Manta rays are usually seen and photographed by rec- reational scuba divers in southeastern Brazil, especially in Keywords Manta birostris Á Seasonality Á Coastal front Á the Laje de Santos Marine State Park (Parque Estadual Melanism Á Laje de Santos Marine State Park Marinho da Laje de Santos; Fig. -

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives Guy Mark William Stevens Doctor of Philosophy University of York Environment August 2016 2 Abstract This multi-decade study on an isolated and unfished population of manta rays (Manta alfredi and M. birostris) in the Maldives used individual-based photo-ID records and behavioural observations to investigate the world’s largest known population of M. alfredi and a previously unstudied population of M. birostris. This research advances knowledge of key life history traits, reproductive strategies, population demographics and habitat use of M. alfredi, and elucidates the feeding and mating behaviour of both manta species. M. alfredi reproductive activity was found to vary considerably among years and appeared related to variability in abundance of the manta’s planktonic food, which in turn may be linked to large-scale weather patterns such as the Indian Ocean Dipole and El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Key to helping improve conservation efforts of M. alfredi was my finding that age at maturity for both females and males, estimated at 15 and 11 years respectively, appears up to 7 – 8 years higher respectively than previously reported. As the fecundity of this species, estimated at one pup every 7.3 years, also appeared two to more than three times lower than estimates from studies with more limited data, my work now marks M. alfredi as one of the world’s least fecund vertebrates. With such low fecundity and long maturation, M. alfredi are extremely vulnerable to overfishing and therefore needs complete protection from exploitation across its entire global range. -

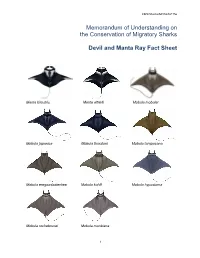

Mobulid Rays) Are Slow-Growing, Large-Bodied Animals with Some Species Occurring in Small, Highly Fragmented Populations

CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Devil and Manta Ray Fact Sheet Manta birostris Manta alfredi Mobula mobular Mobula japanica Mobula thurstoni Mobula tarapacana Mobula eregoodootenkee Mobula kuhlii Mobula hypostoma Mobula rochebrunei Mobula munkiana 1 CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e . Class: Chondrichthyes Order: Rajiformes Family: Rajiformes Manta alfredi – Reef Manta Ray Mobula mobular – Giant Devil Ray Mobula japanica – Spinetail Devil Ray Devil and Manta Rays Mobula thurstoni – Bentfin Devil Ray Raie manta & Raies Mobula Mobula tarapacana – Sicklefin Devil Ray Mantas & Rayas Mobula Mobula eregoodootenkee – Longhorned Pygmy Devil Ray Species: Mobula hypostoma – Atlantic Pygmy Devil Illustration: © Marc Dando Ray Mobula rochebrunei – Guinean Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana – Munk’s Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii – Shortfin Devil Ray 1. BIOLOGY Devil and manta rays (family Mobulidae, the mobulid rays) are slow-growing, large-bodied animals with some species occurring in small, highly fragmented populations. Mobulid rays are pelagic, filter-feeders, with populations sparsely distributed across tropical and warm temperate oceans. Currently, nine species of devil ray (genus Mobula) and two species of manta ray (genus Manta) are recognized by CMS1. Mobulid rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (1 young every 2-3 years), and a late age of maturity (up to 8 years), resulting in population growth rates among the lowest for elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al. 2014; Pardo et al 2016). 2. DISTRIBUTION The three largest-bodied species of Mobula (M. japanica, M. tarapacana, and M. thurstoni), and the oceanic manta (M. birostris) have circumglobal tropical and subtropical geographic ranges. The overlapping range distributions of mobulids, difficulty in differentiating between species, and lack of standardized reporting of fisheries data make it difficult to determine each species’ geographical extent. -

Novel Signature Fatty Acid Profile of the Giant Manta Ray Suggests Reliance on an Uncharacterised Mesopelagic Food Source Low In

Novel signature fatty acid profile of the giant manta ray suggests reliance on an uncharacterised mesopelagic food source low in polyunsaturated fatty acids Katherine B. Burgess, Michel Guerrero, Andrea D. Marshall, Anthony J. Richardson, Mike B. Bennett, Lydie I. E. Couturier To cite this version: Katherine B. Burgess, Michel Guerrero, Andrea D. Marshall, Anthony J. Richardson, Mike B. Bennett, et al.. Novel signature fatty acid profile of the giant manta ray suggests reliance on an uncharacterised mesopelagic food source low in polyunsaturated fatty acids. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2018, 13 (1), pp.e0186464. 10.1371/journal.pone.0186464. hal-02614268 HAL Id: hal-02614268 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02614268 Submitted on 20 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RESEARCH ARTICLE Novel signature fatty acid profile of the giant manta ray suggests reliance on an uncharacterised mesopelagic food source low in polyunsaturated fatty acids Katherine B. Burgess1,2,3*, Michel Guerrero4, Andrea D. Marshall2, Anthony J. -

First Ecological, Biological and Behavioral Insights of the Ocellated Eagle Ray Aetobatus Ocellatus in French Polynesia Cecile Berthe

First ecological, biological and behavioral insights of the ocellated eagle ray Aetobatus ocellatus in French Polynesia Cecile Berthe To cite this version: Cecile Berthe. First ecological, biological and behavioral insights of the ocellated eagle ray Aetobatus ocellatus in French Polynesia. Biodiversity and Ecology. 2017. hal-01690359 HAL Id: hal-01690359 https://hal-ephe.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01690359 Submitted on 23 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MINISTÈRE DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE ÉCOLE PRATIQUE DES HAUTES ÉTUDES Sciences de la Vie et de la Terre MÉMOIRE Présenté par Cécile Berthe pour l’obtention du Diplôme de l’École Pratique des Hautes Études Première approche écologique, biologique et comportementale de la raie aigle à ocelles Aetobatus ocellatus en Polynésie française soutenu le 10 octobre 2017 devant le jury suivant : Clua Eric – Président Iglésias Samuel – Tuteur scientifique Lecchini David – Tuteur pédagogique Bernardi Giacomo – Rapporteur Chin Andrew – Examinateur Mémoire préparé sous -

Observations of Spotted Eagle Rays (Aetobatus Narinari) in the Mexican Caribbean Using Photo-ID

Environ Biol Fish https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-017-0694-y Observations of spotted eagle rays (Aetobatus narinari) in the Mexican Caribbean using photo-ID F. Cerutti-Pereyra & K. Bassos-Hull & X. Arvizu-Torres & K. A. Wilkinson & I. García-Carrillo & J. C. Perez-Jimenez & R. E. Hueter Received: 25 March 2017 /Accepted: 30 October 2017 # Springer Science+Business Media B.V., part of Springer Nature 2017 Abstract The spotted eagle ray is an iconic species for catalog of spotted eagle rays in the Mexican Caribbean the recreational diving and snorkeling industry in the using 1096 photographs submitted by researchers and Mexican Caribbean although it is heavily fished in divers between 2003 and 2016. In total, 282 individual nearby waters of the southern Gulf of Mexico and in spotted eagle rays were identified through photographs Cuba. This species is listed on the IUCN Red List of at nine sites across the Mexican Caribbean. Of these Threatened Species as ‘Near Threatened’ with a de- individuals, 14.9% were resighted at least once at the creasing population trend. Few studies have reported same site. The longest period between re-sighting events on the populations and migrations of spotted eagle rays was 342 days. This is the first study evaluating free- in the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean swimming spotted eagle rays in the Mexican Caribbean Sea, and no regulations currently exist for the fishery or and highlights the value of using photo-ID for monitor- tourism industries in Mexico. Photographic identifica- ing populations of this ray. Because a targeted subsis- tion techniques were used to produce the first photo-ID tence fishery for spotted eagle rays exists in nearby waters, management efforts to monitor and prevent : : overexploitation at key diving locations should be a F.