Lincoln's Body Guard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi'om the original or copy submitted- Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from aity type of conçuter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to r i^ t in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9427761 Lest the rebels come to power: The life of W illiam Dennison, 1815—1882, early Ohio Republican Mulligan, Thomas Cecil, Ph.D. -

President Lincoln and the Altoona Governors' Conference, September

Volume 7 Article 7 2017 “Altoona was his, and fairly won”: President Lincoln and the Altoona Governors’ Conference, September 1862 Kees D. Thompson Princeton University Class of 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/gcjcwe Part of the Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Thompson, Kees D. (2017) "“Altoona was his, and fairly won”: President Lincoln and the Altoona Governors’ Conference, September 1862," The Gettysburg College Journal of the Civil War Era: Vol. 7 , Article 7. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/gcjcwe/vol7/iss1/7 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Altoona was his, and fairly won”: President Lincoln and the Altoona Governors’ Conference, September 1862 Abstract This article explores the long-forgotten Altoona Conference of 1862, when nearly a dozen Union governors met at the Civil War's darkest hour to discuss war strategy and, ultimately, reaffirm their support for the Union cause. This article examines and questions the conventional view of the conference as a challenge to President Lincoln's efficacy as the nation's leader. Rather, the article suggests that Lincoln may have actually welcomed the conference and had his own designs for how it might bolster his political objectives. -

MS-017 Bickham Collection

MS-017 Bickham Collection A Collection of Historical Manuscripts at the Dayton Metro Library Dayton, Ohio Processed By: Lisa P. Rickey, Archivist April 2011 with significant assistance from the earlier efforts of: Elli Bambakidis (2002) Helen Hooven Santmyer (1956) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 4 Biographical Sketch............................................................................................................ 5 Bibliography & Further Reading ...................................................................................... 10 Scope and Content Note.................................................................................................... 12 Box and Folder Listing ..................................................................................................... 13 Item Level Description ..................................................................................................... 16 Series I: William D. Bickham Papers ........................................................................... 16 Box 1, Folder 1: “Weekly Anne Gazette”, 1850 .......................................................... 16 Box 1, Folder 2: Manuscript story about California Gold Rush, Undated ................... 16 Box 1, Folder 3: W. D. Bickham: Military papers, 1861-1864 -

City of Girard Comprehensive Plan

City of Girard Comprehensive Plan May 2017 ~ DRAFT ~ Prepared by: Trumbull County Planning Commission ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS City of Girard Trumbull County Mayor Commissioners James J. Melfi Frank S. Fuda, President Mauro Cantalamessa City Council Daniel E. Polivka Reynold Paolone, President Steve Brooks, 1st Ward Planning Commission Members Mark Standohar, 2nd Ward Lewis Kostoff, Chairman Keith Schubert, 3rd Ward James Shader, Vice Chairman Thomas Grumley, 4th Ward Mauro Cantalamessa, County Commissioner Joseph Shelby, at-Large Frank S. Fuda, County Commissioner Lily Martuccio, at-Large Daniel E. Polivka, County Commissioner John Moliterno, at-Large David Barran Jeff Brown Kathleen O’Leary, Clerk of Council John Mahan Richard Musick City Planning Commission Darlene St. George John Sliwinski George Finelli, Chairman James J. Melfi Jerry Lambert Planning Commission Staff John Latell Trish Nuskievicz, Executive Director Shane Burkholder, Planner II Rental & Zoning Department Christine Clementi, Executive Assistant Rental/ Zoning Coordinator Nicholas I. Coggins, Planner III Julie Edwards, Economic Development Coordinator Rich Fender, Planner II Mitzi Sabella, Administrative Assistant Cheryl Wood, Project Aide II - Housing Specialist TABLE OF CONTENTS INVENTORY Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1-1 Background and Context ................................................................................................ 1-1 Planning Process ............................................................................................................ -

The Tod .B'amily and Connections

Some c.A.ccount of the History of The Tod .B'amily and Connections Compiled by John Tod in the year 1917 HISTORY OF THE TOD F A:tv1IL Y ,, ' ' ,, •, , ) . '. ,.,, .,.,.,, __ jl-' ·)" :,;, ' ....~ ,,· ,/ ' :1 : .;.:,.,, , :~ . ,,,-<:, : .·1 z ',,,, :•:-\ ~ I, / '•,'• , ..•,; ,, . ,. ;1/, ..... Fifty Copies of this book have been printed of . which this Volume is Number TO THE MEMORY OF MY BELOVED AUNT SALLIE TOD, WHOSE LIFE WAS A RAY OF SUNSHINE TO SO MANY PEOPLE, THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED. CONTENTS Page Robert Tod .......................................... 1 David Tod-1746-1827. 7 John Tod-1755-1777... 17 David and Rachel Kent Tod. 19 Samuel Tod-1775 ....... .-. 21 Isabella Tod-1778-1848................................ 23 John Tod-1?80-1830.. 33 Charlotte Low Tod-1782-1798. 39 David Low Tod-1784-1829. 41 George Tod-1773-1841.... 45 Sally Isaacs Tod-1778-1847........................... 55 George and Sally Isaacs Tod. 65 Charlotte Lowe Tod-1799-1815 ............. ·. 67 Jonathan Ingersoll Tod-1801-1859. 69 Mary Isaacs Tod-1802-1869 ........................... 75 Julia Ann Tod-1807-1885. 77 Grace Ingersoll Tod-1811-1867. 83 George Tod, Jr.,-1816-1881.. 89 David Tod-1805-1868. 93 Maria Smith Tod-1813-1901. • . • . 121 Smith Fatn.ily. 123 CONTENTS Page David and Maria Smith Tod ...................... ~ . 130 Charlotte Tod-1833-1868. 131 John Tod-1834-1896. .. 135 Henry Tod-1838-1905. 139 John Tod-1870 ....... ~ ............................... 143 Henry Tod, Jr.-1877-1902 ................ ·. 145 George Tod-1840-1908 ........................ ·.. 149 William Tod-1843-1905. • . 155 David Tod-1870. 159 William Tod, Jr.-1874-1890 ........................... 161 Fred Tod-1885. 163 Grace Tod Arrel-1847 ............................ ~ . 165 David Tod Arrel-1878. 166 Frances Arrel Parson. -

![12/05/2005 Case Announcements #2, 2005-Ohio-6408.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3450/12-05-2005-case-announcements-2-2005-ohio-6408-1143450.webp)

12/05/2005 Case Announcements #2, 2005-Ohio-6408.]

CASE ANNOUNCEMENTS AND ADMINISTRATIVE ACTIONS December 5, 2005 [Cite as 12/05/2005 Case Announcements #2, 2005-Ohio-6408.] MISCELLANEOUS ORDERS On December 2, 2005, the Supreme Court issued orders suspending 13,800 attorneys for noncompliance with Gov.Bar R. VI, which requires attorneys to file a Certificate of Registration and pay applicable fees on or before September 1, 2005. The text of the entry imposing the suspension is reproduced below. This is followed by a list of the attorneys who were suspended. The list includes, by county, each attorney’s Attorney Registration Number. Because an attorney suspended pursuant to Gov.Bar R. VI can be reinstated upon application, an attorney whose name appears below may have been reinstated prior to publication of this notice. Please contact the Attorney Registration Section at 614/387-9320 to determine the current status of an attorney whose name appears below. In re Attorney Registration Suspension : ORDER OF [Attorney Name] : SUSPENSION Respondent. : : [Registration Number] : Gov.Bar R. VI(1)(A) requires all attorneys admitted to the practice of law in Ohio to file a Certificate of Registration for the 2005/2007 attorney registration biennium on or before September 1, 2005. Section 6(A) establishes that an attorney who fails to file the Certificate of Registration on or before September 1, 2005, but pays within ninety days of the deadline, shall be assessed a late fee. Section 6(B) provides that an attorney who fails to file a Certificate of Registration and pay the fees either timely or within the late registration period shall be notified of noncompliance and that if the attorney fails to file evidence of compliance with Gov.Bar R. -

Hay, John. Inside Lincoln's White House: the Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay

Hay, John. Inside Lincoln's White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay. Edited by Michel Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997. White House besieged, James Lane and Kansas, 1 Threat to Lincoln's life, 1-2 Ward Hill Lamon and Cassius Clay, 2 Guarding White House, 2 Maryland, Baltimore, troops, Scott, Seward, 3 Massachusetts in capitol, 4-5 James Lane, 5, 9, 13 Baltimore secessionists, 5-7 John B. Magruder joining Confederates, 5 Chase and confusing of orders, 6 Cassius Clay, 8 Food shortages in besieged Washington, 8 Delaware, 8-9 Southern newspapers and letters, badly written, 9-10 Jefferson Davis and Lincoln, Confederate constitution, 10 Lincoln and troops and siege of Washington, 11 Dahlgren, 11 Lincoln and strategy, 11 Benjamin F. Butler and Maryland legislature, 12 Carl Schurz, , Lincoln, 12-14 William F. Channing, slavery, abolition, martial law, 12-13 Suspension of habeas corpus, 13 Indians, 14 Virginia Unionists, 15 Baltimore, 16 Ellsworth, 16 Fernando Wood, Isham Harris, Lincoln, 17 Lincoln and Maryland secessionists, 17-18 Hannibal Hamlin, 18 Cairo, Kentucky neutrality, 19 Brown, Orville Hickman, abolition, slavery, 19-20 Ellsworth, Zouaves, 20-21 Jefferson Davis, secession, right of revolution, 21 Anderson, Robert, 21 Dahlgren gun, 22 Ellsworth Zouaves, Willard Hotel, fire, 22-23 Carl Schurz, fugitive slaves, 22-23 Secession, habeas corpus, 28 Lincoln and cotton trade, 30-31 Benjamin F. Butler, Fremont, Wool, 31 Seward, 40 Emancipation Proclamation, 40-41 Salmon P. Chase, 40. Charleston, South Carolina coast, 43ff Fort Pulaski, 46-48 Florida, 48ff African American singing, 49, 58-59 Lincoln, Meade, Gettysburg, 61-66, 68 Lincoln and soldier punishment, executions, 64 Salmon P. -

Abraham Lincoln Papers

Abraham Lincoln papers From John W. Forney to Abraham Lincoln, October 24, 1864 {Private.} Philadelphia, October 24th 1864. Dear Mr. Lincoln; Before starting upon my last campaign in this Presidential election, I take the liberty of asking you to read this letter — which will be presented to you by my son, John W. Forney, Jr., — on which I beg of you to ponder upon the views I will express to you. You were nominated and elected as a Republican, and you owe your seat to the division of the Democratic party in the two national conventions which took place at Charleston and at Baltimore. When Mr. Buchanan made a test of the Lecompton and the English bills, I foresaw that the slaveholders intended either to force one of their creatures upon the Democratic ticket for President, or to divide the Democratic party, and so to divide the Union; — but I had no idea that they would make your election a pretext for the separation of the Republic. Nevertheless I was extremely anxious to bring them to the test, and 1 hence I did my uttermost to strengthen Judge Douglas in his honest antagonism to those who were his personal foes, and to prepare him for the bold and manly stand which he assumed after your nomination by the Chicago convention, in 1860. His tour through the Southern states, in which he insisted that your inevitable constitutional election would be no cause for an assault upon the Union, awake[n]ed all my sensibilities, and I was not surprised at the close of it, when you were chosen to the place you now so honorably occupy, that you should have paid him the tribute which such unselfish patriotism deserved. -

^24.DE^Wilpm.PERRY

FOUR GENERATIONS, DESCENDANTS • PERRY ^24.DE^WilPM. Calibrated Their Fiftieth Wedding Anniversary. MRS. PHILIP LEPPLA. Mr. and Mrs. Philip Leppla of this place celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary at their pleasant home here last Sunday. Owing to the recent death of their youngest daughter, Mrs. Carl L. Gale of Columbus, which occurred a few days ago, the affair was celebrated in a quiet and unostentatious manner, only the immediate family being present. This aged couple were united in marrirge at Canton, Ohio, November 6, 1854, by Rev. Herbruck, a Lutheran minister. Mrs. Leppla, whose maiden name was Louise Ittner, was 16 years of age and her hus band 26. Thirteen children were born to this union, three dying in infancy; the eldest son, Godfrey, died about three years ago, and the youngest daughter, Mrs. Gale, three weeks ago. The eight living children are Mrs. Wm. A. Gerber, Mrs. C. Kaemmerer and George Leppla of Columbus; William and Charles Leppla of Barber ton; Mrs. GK W. Weimer, Mrs. A. G. Schmidt and Philip Leppla, Jr., of this place. There are nineteen grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Mr. Leppla was born in Bavaria, Germany, May 13,1828, of Lutheran parent age, and came to America in 1849, locating at Winesburg, where he carried on the business of blacksmithing, which he followed until about ten years ago. Mrs. Leppla was born at Winesburg, October 6, 1838. In 1859 they located in Millersburg, since which time they have made their | home here. Both are enjoying good health, active for their years, and are spend Here is a picture of four generations in the direct line, all bearing the ing the latter days of their lives in a quiet and pleasant manner. -

A Complete History of Fairfield County, Ohio

" A COMPLETE HISTORY FAIRFIELD COUNTY, OHIO, HERVEY SCOTT, 1795-187 0. SIEBERT & L1LLEY, COLUMBUS, I'lllO : L877. r^-Tf INDEX. PAGE. Bar of Lancaster 16 Baptists, New School 120» Band of Horse-thieves 148 Births and Deaths 157 Binninger, Philip 160 Banks of Lancaster 282 Commerce of Fairfield County 18 Choruses 27 Carpenter's Addition 34 County Jail , 36 Court of Common Pleas 52 Canal Celebration 59 Court of Quarter-Sessions 78 County Fair 96 Catholic Church 138 County Officers 144 Colored Citizens of Lancaster 281 Cold Spring Rescue 289 Conclusion 298 Dunker Church 142 Enterprise 20 Episcopal Church 135 Emanuel's Church, St 137 Evangelical Association (Albright) 140 First Settlement 4 First Born 7 First Mails and Post-route 12 Fourth of July 31 Finances of Lancaster in 1827 32 Finances of Fairfield in 1875 36 Fairfield County in 1806 36 Fairfield County in the War of 1812 79 Growth of Lancaster 11 Ghost Story 61 Grape Culture 68 General Sanderson's Notes 98 Germau Reform Church 136 IV INDEX. PAGE. Gas-Light and Coke Company 281 Governors of Ohio 287 Horticultural Society 119 Hocking Valley Canal 150 Introduction 1 Inscriptions in Kuntz's Graveyard 61 Incorporation 21 Judges of Court 278 Knights of Pythias 73 Knights of Honor 73 Knights of St. George 75 Lancaster 6 Lancaster Gazette 5S Lutheran Church, first English 136 Land Tax 160 Mount Pleasant 10 Medical Profession 16 Miscellaneous 21 Miscellaneous 65 Masonic 69 Methodist Church 122 New Court-house 35 Nationality 156 01 1 Religious Stanzas 23 Old Plays 28 Ohio Eagle 57 Other Papers 59 Odd Fellowship 71 Ornish Mennonite Church 139 Primitive State of the Country 2 Public Square 34 Physicians 59 Patrons of Husbandry , 74 Political 120 Protestant Methodist 128 Pleasant Run Church 129 Presbyterian Church 131 Public Men t 152 Phrophesy 297 Presidents of United States 288 Ruhamah Green (Builderback) 8 Relics 56 Rush Creek Township in 1806 157 Refugee Lands 80 Reform Farm 80 PAGE. -

Civil War Dissent in the Cincinnati Area

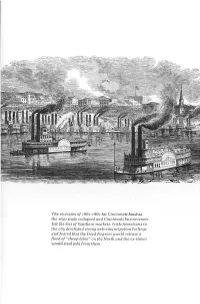

The recession of 1861-1862 hit Cincinnati hard as the river trade collapsed and Cincinnati businessmen felt the loss of Southern markets. Irish-Americans in the city developed strong anti-emancipation feelings and feared that the freed Negroes would release a flood of "cheap labor" on the North and the ex-slaves •would steal jobs from them. Sound and Fury: Civil War Dissent in the Cincinnati Area by Frank L. Klement 'T'he word "dissent" bears a negative connotation. The Oxford dictionary defines it as "difference of opinion or sentiment."1 Simply, a dissenter is one who disagrees with majority views and with the turn of events. Dissenters of Civil War days did not agree with majority opinion or prevailing views, and they opposed the course of events of the 1861-1865 era. The Civil War was a complex, four-year event with widespread effects and discernible facets. Historians, looking back at the Civil War a hundred years later, discern at least four separate if related aspects: (1) The use of armed might or coercion as a means to save the Union; (2) The centralization of power in Washington as the federal union evolved into a strong national gov- ernment; (3) A social revolution, featuring the emancipation of slaves and the extension of rights to the black man; (4) The forces of industrialism gaining control of the government, bringing an end to the alliance of the agricultural South and the West. Dissenters of Civil War days, then, were citizens who opposed one or all four aspects of the war—they may have favored compromise rather than force to restore the Union; they may have feared that the central government was evolving into a despotism; they may have been racists opposing emancipation; or they may have been Western sectionalists opposing domination of the gov- ernment by the lords of the looms and the masters of capital.