Practical Theology Reflecting on the Public Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classic Albums: the Berlin/Germany Edition

Course Title Classic Albums: The Berlin/Germany Edition Course Number REMU-UT 9817 D01 Spring 2019 Syllabus last updated on: 23-Dec-2018 Lecturer Contact Information Course Details Wednesdays, 6:15pm to 7:30pm (14 weeks) Location NYU Berlin Academic Center, Room BLAC 101 Prerequisites No pre-requisites Units earned 2 credits Course Description A classic album is one that has been deemed by many —or even just a select influential few — as a standard bearer within or without its genre. In this class—a companion to the Classic Albums class offered in New York—we will look and listen at a selection of classic albums recorded in Berlin, or recorded in Germany more broadly, and how the city/country shaped them – from David Bowie's famous Berlin trilogy from 1977 – 79 to Ricardo Villalobos' minimal house masterpiece Alcachofa. We will deconstruct the music and production of these albums, putting them in full social and political context and exploring the range of reasons why they have garnered classic status. Artists, producers and engineers involved in the making of these albums will be invited to discuss their seminal works with the students. Along the way we will also consider the history of German electronic music. We will particularly look at how electronic music developed in Germany before the advent of house and techno in the late 1980s as well as the arrival of Techno, a new musical movement, and new technology in Berlin and Germany in the turbulent years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, up to the present. -

Stockhausen's Cosmic Pulses

Robin Maconie: Stockhausen’s Cosmic Pulses 2009–14 (copyright) 1 Stockhausen’s Cosmic Pulses ROBIN MACONIE Some people chase tornados; others go after black holes. From the late 1950s Stockhausen was fascinated by the idea of sounds in rotation and how to realise them in a technical sense, by means of an array of loudspeakers. Completed in 2007, Cosmic Pulses is Stockhausen’s final electronic composition.1 For a number of reasons I believe the composer knew it would be his last. The work was completed in a rush. In many ways, notably in terms of the sound material, which is very basic, it remains a sketch. The music can be described as a massive rotating sound mass, composed in 24 separately spinning frequency layers. The work thickens gradually to 24 layers, then reduces symmetrically upward in an ascending spiral that ends quite abruptly. An audience may experience the sensation of falling headlong into a black hole, or, if one is an optimist, of being carried aloft on the whirlwind like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. A tornado is an effect of a natural imbalance between temperature layers in the atmosphere, tipped into motion by the earth’s rotation, which moves progressively faster toward the equator. The rotating air mass that results spirals upwards and generates a powerful electrical charge. A black hole by comparison is an effect of gravitation creating an imbalance in spacetime. The rotational process that results spirals downward or inward and leads to the extinction of reality as we know it, or again, if one is an optimist, creates a wormhole leading either into another universe, or into our own universe at Robin Maconie: Stockhausen’s Cosmic Pulses 2009–14 (copyright) 2 another point in time. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Works for Ensemble English

composed 137 works for ensemble (2 players or more) from 1950 to 2007. SCORES , compact discs, books , posters, videos, music boxes may be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag . A complete list of Stockhausen ’s works and CDs is available free of charge from the Stockhausen-Verlag , Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax: +49 [0 ] 2268-1813; e-mail [email protected]) www.stockhausen.org Karlheinz Stockhausen Works for ensemble (2 players or more) (Among these works for more than 18 players which are usu al ly not per formed by orches tras, but rath er by cham ber ensem bles such as the Lon don Sin fo niet ta , the Ensem ble Inter con tem po rain , the Asko Ensem ble , or Ensem ble Mod ern .) All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are pub lished by Uni ver sal Edi tion in Vien na, with the excep tion of ETUDE, Elec tron ic STUD IES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE , KON TAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYM NEN , which are pub lished since 1993 by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Start ing with work num ber 30, all com po si tions are pub lished by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , Ket ten berg 15, 51515 Kürten, Ger ma ny, and may be ordered di rect ly. [9 ’21”] = dura tion of 9 min utes and 21 sec onds (dura tions with min utes and sec onds: CD dura tions of the Com plete Edi tion ). -

KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN the 24 Hours of The

KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN KLANG The 24 Hours of the Day The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Analog Arts present the US premiere of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s KLANG cycle. The production consists of the 21 pieces Stockhausen managed to finish before his death in 2007. For more information on KLANG, please visit www.analogarts.org/klangnyc. FRIDAY, March 25, 2016 Metropolitan Museum Auditorium The Met Breuer 5:00 pm EDENTIA, 20th Hour Soprano saxophone and tape.19’ 5:30 pm HARMONIEN (Harmonies), 5th Hour GLÜCK (Bliss), 8th Hour Flute, trumpet, and bass clarinet, 15’ Bassoon, English horn, and oboe, 5:45 pm COSMIC PULSES,13th Hour US premiere. 40’ Tape. 32’ 6:15 pm NATÜRLICHE-DAUERN (Natural rd th 6:30 pm Durations), 3 Hour JERUSEM, 18 Hour Piano, NY premiere. 45’ Tenor and tape, US Premiere. 21’ 7:00 pm NEBADON, 17th Hour The Metropolitan Museum GLANZ (Brilliance), 10th Hour Horn and tape, NY premiere. 22’ 1000 Fifth Avenue Bassoon, clarinet, viola, oboe, trumpet, 7:30 pm PARADIES, 21st Hour trombone, tuba, US premiere. 40’ Flute and tape, US premiere. 19’ The Met Breuer 7:45 pm HIMMELS-TÜR (Heaven’s Door), 4th Hour 945 Madison Avenue Percussion, little girl, NY premiere. 21’ 8:15 pm HAVONA, 14th Hour The Cloisters Bass and tape. NY premiere. 25’ 99 Margaret Corbin Drive SATURDAY, March 26, 2016 Metropolitan Museum Auditorium The Met Breuer The Cloisters 11:00 am COSMIC PULSES, 13th Hour HIMMELFAHRT (Ascension), 1st Hour 11:15 am UVERSA, 16th Hour Tape. 32’ Organ, soprano, tenor. NY premiere. 39’ Basset horn and tape, US premiere. -

KLANG Schedule 2018.3

KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN’s Presented by Elizabeth Huston and Analog Arts at FringeArts KLANG: The 24 Hours of the Day 140 North Columbus Boulevard Philadelphia, PA 19106 KLANG Up Close (Studio) KLANG Up Close (Studio) 10:00 a.m. 5. HARMONIEN for flute, bass clarinet, and trumpet 10:00 a.m. 5. HARMONIEN for flute, bass clarinet, and trumpet (Studio, Theater, La Peg) (Studio, Theater, La Peg) 10:15 a.m. 3. NATÜRLICHE DAUERN for piano 10:15 a.m. 3. NATÜRLICHE DAUERN for piano 10:45 a.m. 9. HOFFNUNG for violin, viola, and cello 10:45 a.m. 9. HOFFNUNG for violin, viola, and cello 11:20 a.m. 17. NEBADON for French horn and tape 11:20 a.m. 20. EDENTIA for soprano saxophone and tape 11:45 a.m. 3. NATÜRLICHE DAUERN for piano 11:40 p.m. 8. GLÜCK for bassoon, English horn, and oboe 12:15 p.m. 11. BALANCE for flute, English horn, and bass clarinet 12:20 p.m. 3. NATÜRLICHE DAUERN for piano 12:50 p.m. 11. TREUE for E-flat clarinet, basset horn, and bass clarinet Modular KLANG (Studio & Theater) Modular KLANG (Studio & Theater) 1:00 p.m. 19. URANTIA for soprano and tape (Studio) 1:20 p.m. 7. BALANCE for flute, English horn, and bass clarinet (Studio) 13. COSMIC PULSES for tape (Theater) 5. HARMONIEN for flute (Theater) 1:35 p.m. 7. TREUE for E-flat clarinet, basset horn, and bass clarinet (Studio) 1:55 p.m. 19. URANTIA for soprano and tape (Studio) 8. GLÜCK for bassoon, English horn, and oboe (Theater) 13. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen

What to Expect: Welcome to KLANG! There is a lot happening Elizabeth Huston and Analog Arts Present today, so we recommend you take a quick look at this packet to orient yourself. Inside you will find the schedule and location Karlheinz Stockhausen of performances, the schedule and location of talks, interviews, and Q&As, and a guide to all amenities that will be available as you navigate this marathon. First, let’s start with the rules. The day is broken up into four sections. You may have purchased a ticket for just one section, KLANG or you may have purchased an all-day pass. Either way, please THE 24 HOURS OF THE DAY familiarize yourself with the rules for each section, as each is a distinctly different experience. PHILADELPHIA, PA • April 7–8, 2018 Welcome to KLANG: At 10am sharp you will be welcomed by a welcome to enter and exit the spaces during performances. At performance of all three versions of HARMONIEN performed in all other times, please be courteous and enter and exit between La Peg, the Theater, and the Studio simultaneously. Feel free to performances. wander between the spaces, eventually settling in the Studio for… KLANG Immersion (4pm–7pm): A mix between KLANG up Close and KLANG in Concert, this time period showcases some of the KLANG up Close (10am–1pm): This time period is an opportu- most well known parts of KLANG, while still allowing the audi- nity to have an intimate concert experience with KLANG. This ence to be up close with the music. Taking place entirely in the will take place entirely in the Studio. -

TEXTE Zur MUSIK 199 8 –2007

Karlheinz Stockhausen TEXTE zur MUSIK 199 8 –2007 Band 17 KLANG-Zyklus – Geist und Musik – Ausblicke Im Auftrag der Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik herausgegeben von Imke Misch Stockhausen-Verlag Kürten 2014 First edition 2014 Published by Stockhausen-Verlag 51515 Kürten, Germany Alle Rechte vorbehalten / All rights reserved. Kopieren gesetzlich verboten / Copying prohibited by law. Das Vorwort der Herausgeberin zu den TEXT EN zu r MUSIK 1991–1998 und 1998 –2007 befindet sich in Band 11 . Photo auf de m Umschlag vorn e: Stockhausen im Juli 2007 während der Stockhausen-Kursen Kürten Abbildung auf dem Umschlag hinten : Formschema von COSMIC PULSES, 13. Stunde aus KLANG © Copyright Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 2014 Satz: Kathinka Pasveer ISBN 978-3-9815317-7-0 Die TEXTE zur MUSIK 1991 –1998 sind in vier Bände mit zehn Kapiteln gegliedert: Band 11 I Nachsätze: Zu KREUZSPIEL (1951) bis LIBRA (1977) II Werktreue III Ergänzendes zu LICHT Band 12 IV FREITAG aus LICHT V Neue Konzertpraxis Band 13 VI MITTWOCH aus LICHT VII Elektronische Musik Band 14 VIII Über Musik, Kunst, Gott und die Welt IX Blickwinkel X Komponistenalltag V Die TEXTE zur MUSIK 1998 –2007 sind in drei Bände mit neun Kapiteln gegliedert: Band 15 I SONNTAG aus LICHT II Neue Einzelwerke III Stockhausen-Kurse Kürten Band 16 IV LICHT-Reflexe V Seitenzweige VI Klangproduktion / Klangprojektion Band 17 VII KLANG-Zyklus VIII Geist und Musik IX Ausblicke VI TEXT E zur MUSI K Band 17 Inhalt VII KLANG-Zyklus HIMMELFAHRT – 1. Stunde (Partiturvorwort) ...................... 1 FREUDE – 2. Stunde (Partiturvorwort) ................................... 11 NATÜRLICHE DAUERN – 3. Stunde (Partiturvorwort) ........ 15 HIMMELS-TÜR – 4. -

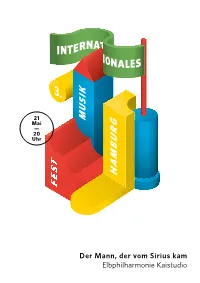

Der Mann, Der Vom Sirius Kam Elbphilharmonie Kaistudio

21 Mai — 20 Uhr Der Mann, der vom Sirius kam Elbphilharmonie Kaistudio 20 Uhr Elbphilharmonie Kaistudio 21 — Mai BMW 7er DER ANSPRUCH VON MORGEN DER MANN, DER VOM SIRIUS KAM Thomas von Steinaecker Autor David von Bassewitz Zeichner Paul Hübner Musikalische Konzeption, Klangregie Präsentation der neuen Graphic Novel »Der Mann, der vom Sirius kam« von Thomas von Steinaecker und David von Bassewitz. Musik: Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) Karlheinz Stockhausen Tierkreis (Auszüge) (1975) BMW IST LANGJÄHRIGER PARTNER DER ELBPHILHARMONIE Abbildung zeigt Sonderausstattungen. 8331_BMW_Luxury_7er_Elbphilharmonie_Abendprogramm_148x210.indd 1 06.04.2018 08:48:43 MUSIK ALS UTOPIE Wie Karlheinz Stockhausen den Klang der Zukunft schuf. Von Thomas von Steinaecker Darmstadt, Sommer 1951. Bei den »Internationalen Ferienkursen für Neue Musik« herrscht Aufbruchsstimmung. Tagsüber besuchen die jungen Komponisten aus aller Welt Seminare mit Titeln wie »La musique concrète« oder eine Einführung in die Zwölftonmusik, die Theodor W. Adorno anstelle des erkrankten Arnold Schönberg hält. Abends diskutiert man auf den idyllischen Wiesen der Marien- höhe mit Blick über die Stadt, die noch in Trümmern liegt. Mich hat die Vorstel- lung immer berührt, wie hier eine Generation junger Komponisten buchstäblich im Schatten der Apokalypse, die zu diesem Zeitpunkt nur sechs Jahre zurück und ein paar hundert Meter Luftlinie entfernt liegt, mit einem Eifer an der Neuerfindung der eigenen Mittel und Methoden arbeitet, der in der Musikgeschichte einzigartig ist. Ausgerechnet in den heute oft als hoffnungslos verstaubt geltenden und angeblich von »Adenauer-Mief« eingehüllten 1950er Jahre legten die Künstler eine Experimentierfreudigkeit an den Tag, die uns heute zuweilen ziemlich alt aussehen lässt. Interessanterweise gab sich die Musik von allen Künsten am explizitesten utopisch. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen: BIOGRAPHY English

SHORT BIOG RA PHY Karl heinz Stock hau sen 1928 Born Wednesday, August 22nd in Mödrath near Cologne. 1947 – 51 In Cologne, stud ied at the State Con ser va to ry of Music (piano, music edu ca tion) and at the University of Cologne (Ger man phi lol o gy, phi los o phy, musi col o gy). Since l950 First com po si tions and per for manc es of his own works. (In the fol low ing enumeration, only a few of the more than 370 works and world premières are men tioned.) 1951 Serial Music: KREUZ SPIEL (CROSS-PLAY), FOR MEL (FOR MU LA), etc. Married Doris Andreae; four chil dren with Doris: Suja (1953), Chris tel (1956), Mark us (1957), Majel la (1961). 1952 Point Music: SPIEL (PLAY), KLAVIERSTÜCKE (PIANO PIECES), SCHLAGTRIO (PER CUS SIVE TRIO), PUNK TE (POINTS), KON TRA-PUNK TE (COUN TER- POINTS) etc. Attend ed Olivi er Messiaen’s cours es in rhyth mics and aes thet ics in Paris. Experi ments in the “ musique concrète” group at the French radio in Paris, and real isa tion of an ETUDE ( musique concrète). First syn the sis of sound-spec tra with elec tron ical ly gen er at ed sine tones. Since 1953 Per ma nent col lab o ra tor at the Studio for Elec tron ic Music of the West Ger man Radio in Cologne (artis tic direc tor from 1963–1977, artis tic con sul tant until 1990). Lec tur er at the annu al International Summer Cours es for New Music in Darm stadt from 1953 until 1974, and in 1996. -

Popular Music in Germany: History, Culture, Politics

Course Title Popular Music in Germany: History, Culture, Politics The History of Electronic Music in Germany Course Number REMU-UT.9811D01 SPRING 2020 Syllabus last updated on: 23-December-2019 Lecturer Contact Information Heiko Hoffmann Course Details Wednesdays, 6:15pm to 7:30pm Location: Rooms will be posted in Albert before your first class. Please double check whether your class takes place at the Academic Center (BLAC – Schönhauser Allee 36, 10435 Berlin) or at St. Agnes (SNTA – Alexandrinenstraße 118–121, 10969 Berlin). Prerequisites No pre-requisites Units earned 2 credits Course Description From Karlheinz Stockhausen and Kraftwerk to Giorgio Moroder, D.A.F. and the Euro Dance of Snap!, the first half of class considers the history of German electronic music prior to the Fall of the Wall in 1989. We will particularly look at how electronic music developed in Germany before the advent of house and techno in the late 1980s. One focus will be on regional scenes, such as the Düsseldorf school of electronic music in the 1970s with music groups such as Can and Neu!, the Berlin school of synthesizer pioneers like Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze and Manuel Göttsching, or Giorgio Moroder's Sound of Munich. 1 Students will be expected to competently identify key musicians and recordings of this creative period. The second half of the course looks more specifically at the arrival of techno, a new musical movement, and new technology in Berlin and Germany in the turbulent years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall, up to the present. Indeed, Post-Wall East Berlin, full of abandoned spaces and buildings and deserted office blocks, was the perfect breeding ground for the youth culture that would dominate the 1990s and led techno pioneers and artists from the East and the West to take over and set up shop. -

STOCKHAUSEN-VERLAG Price List English

Stockhausen-Verla g Price list 2018 All Stockhausen scores which are published by Universal Edition , Vienna, may also be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag (prices on request) . scores / books / posters / music boxes: Scores Quantity € 3 x REFRAIN 2000 ............................................................ –––– 45.00 AM HIMME L WANDR E ICH . ............................................ –––– 38.00 AMOUR for clarinet ........................................................... –––– 22.00 for flute ............................................................... –––– 22.00 for saxophone . ..................................................... –––– 33.00 ANTRAG ......................................................................... –––– 35.00 ARGUMENT .................................................................... –––– 46.00 ARIES ............................................................................. –––– 24.50 ATMEN GIBT DAS LEBEN .............................................. –––– 50.50 AVE ................................................................................. –––– 76.00 th BALANCE – 7 Hour from KLANG ................................... –––– 60.00 BASSETSU ...................................................................... –––– 40.00 BASSETSU-TRIO ............................................................. –––– 34.00 Betmoment ....................................................................... –––– 60.00 BIJOU .............................................................................. –––– -

2008 Performances Update

Stock hau sen Aufführungen / Per for manc es 2013 Saturday, Jan. 5th, 7:30 p.m. Paris , Palais Garnier (Information: www.preljocaj.org ) Choreography of HELICOPTER STRING QUARTET and SONNTAGS-ABSCHIED (ELDORADO) Sunday, Jan. 6th, 2:30 p.m. Paris , Palais Garnier (Information: www.preljocaj.org ) Choreography of HELICOPTER STRING QUARTET and SONNTAGS-ABSCHIED (ELDORADO) Monday, Jan. 7th, 7:30 p.m. Paris , Palais Garnier (Information: www.preljocaj.org ) Choreography of HELICOPTER STRING QUARTET and SONNTAGS-ABSCHIED (ELDORADO) Tuesday, Jan. 8th, 7:30 p.m. Paris , Palais Garnier (Information: www.preljocaj.org ) Choreography of HELICOPTER STRING QUARTET and SONNTAGS-ABSCHIED (ELDORADO) Wednesday, Jan. 9th, 7:30 p.m. Paris , Palais Garnier (Information: www.preljocaj.org ) Choreography of HELICOPTER STRING QUARTET and SONNTAGS-ABSCHIED (ELDORADO) Thursday, Jan. 10th, 7:30 p.m. Paris , Palais Garnier (Information: www.preljocaj.org ) Choreography of HELICOPTER STRING QUARTET and SONNTAGS-ABSCHIED (ELDORADO) Monday, January 21st Berlin, Volksbühne Berlin (Information: www.mdjstuttgart.de ) MENSCHEN, HÖRT (MANKIND, HEAR) for vocal sextet Tuesday, January 2nd Stuttgart, Theaterhaus (Information: www.mdjstuttgart.de ) MENSCHEN, HÖRT (MANKIND, HEAR) for vocal sextet Friday, Jan. 25th, 8 p.m. Berlin , Sophienkirche (Information: Ultraschall Festival Berlin) KLANG – 3rd Hour : NATÜRLICHE DAUERN (NATURAL DURATIONS) for piano Wedn., Febr. 13th, 9 p.m. Vancouver, Roy Barnett Hall, University of British Columbia School of Music (Information: Liam Hockley <[email protected]> ) TANZE LUZEFA! for bass clarinet Thursday, Febr. 14th, 9 p.m. Torino, Teatro Baretti (Information: http://www.cineteatrobaretti.it/teatro/alla- musa/harlekin.htm ) HARLEKIN (HARLEQUIN) for clarinet Thursd., Febr. 14th, 8:30 p.m.