3.2. Territorial Restructuring and Ethnicity in Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

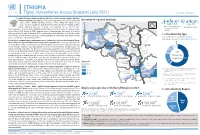

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

OCHA East Hub Easthararghe Zone of Oromia: Flash Floods 290K 13

OCHA East Hub East Hararghe Zone of Oromia: Flash floods Flash Update No. 1 As of 26 August 2020 HIGHLIGHTS Districts affected by flash floods as of 20 August 2020 • 290,185 people (58,073HHs) were affected due to the recent flood and landslide • 169 PAs in 13 districts (Haromaya, Goro Muxi, Kersa Melka Belo, Bedeno, Meta, Deder, Kumbi, Giraw, Kurfa Calle, Kombolcha, Jarso and Goro Gutu) were affected. • Over 42,000IDPs in those affected woredas were also affected including secondary displacement in some areas like the 56HH IDPs in Calanqo city of Metta woreda • 970 houses were damaged out of which 330 were totally damaged resulting to the displacement for 1090 people. Moreover,22,080 hectares of meher plantations were damaged impacting 18885 people in 4 districts and landslides on 2061 hectares affected 18785 people. A total of 18 human deaths as well as 135 livestock deaths reported. • 4 roads with total length of 414kms were partially damaged which might cause physical access constraints to 4-5 woredas of the zone. 290K 13 affected Districts affected people SITUATION OVERVIEW East Hararghe zone is recurrently affected by flood impact. Chronically,9 woredas of the zone, namely, Kersa, Melak Belo, Midhega Tola, Bedeno, Gursum, Deder, Babile, Haromaya ad Metta were prone to flooding. The previous flood in May affected 8 of the these woredas were 10,067 HHs (over 60,000 people) in 62 kebeles were affected. During this time, over 2000 hectares of Belg plantations were damaged. Only Babile woreda was reached with few assistances from some partners. The NMA predicted that above normal rainfall will likely to happen in the Eastern part after June. -

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008)

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008) ma, maa (O) why? HES37 Ma 1258'/3813' 2093 m, near Deresge 12/38 [Gz] HES37 Ma Abo (church) 1259'/3812' 2549 m 12/38 [Gz] JEH61 Maabai (plain) 12/40 [WO] HEM61 Maaga (Maago), see Mahago HEU35 Maago 2354 m 12/39 [LM WO] HEU71 Maajeraro (Ma'ajeraro) 1320'/3931' 2345 m, 13/39 [Gz] south of Mekele -- Maale language, an Omotic language spoken in the Bako-Gazer district -- Maale people, living at some distance to the north-west of the Konso HCC.. Maale (area), east of Jinka 05/36 [x] ?? Maana, east of Ankar in the north-west 12/37? [n] JEJ40 Maandita (area) 12/41 [WO] HFF31 Maaquddi, see Meakudi maar (T) honey HFC45 Maar (Amba Maar) 1401'/3706' 1151 m 14/37 [Gz] HEU62 Maara 1314'/3935' 1940 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] JEJ42 Maaru (area) 12/41 [WO] maass..: masara (O) castle, temple JEJ52 Maassarra (area) 12/41 [WO] Ma.., see also Me.. -- Mabaan (Burun), name of a small ethnic group, numbering 3,026 at one census, but about 23 only according to the 1994 census maber (Gurage) monthly Christian gathering where there is an orthodox church HET52 Maber 1312'/3838' 1996 m 13/38 [WO Gz] mabera: mabara (O) religious organization of a group of men or women JEC50 Mabera (area), cf Mebera 11/41 [WO] mabil: mebil (mäbil) (A) food, eatables -- Mabil, Mavil, name of a Mecha Oromo tribe HDR42 Mabil, see Koli, cf Mebel JEP96 Mabra 1330'/4116' 126 m, 13/41 [WO Gz] near the border of Eritrea, cf Mebera HEU91 Macalle, see Mekele JDK54 Macanis, see Makanissa HDM12 Macaniso, see Makaniso HES69 Macanna, see Makanna, and also Mekane Birhan HFF64 Macargot, see Makargot JER02 Macarra, see Makarra HES50 Macatat, see Makatat HDH78 Maccanissa, see Makanisa HDE04 Macchi, se Meki HFF02 Macden, see May Mekden (with sub-post office) macha (O) 1. -

Refugee Status Appeals Authority New Zealand

REFUGEE STATUS APPEALS AUTHORITY NEW ZEALAND REFUGEE APPEAL NO 76528 AT CHRISTCHURCH Before: A R Mackey (Chairman) Counsel for the Appellant: J Mirkin Appearing for the Department of Labour: No appearance Date of Hearing: 3 August 2010 Date of Decision: 27 August 2010 DECISION [1] This is an appeal against the decision of a refugee status officer of the Refugee Status Branch (RSB) of the Department of Labour (DOL), declining the grant of refugee status to the appellant, a national of Ethiopia, of Tigrayan ethnicity. He was brought up in the Orthodox Christian faith. INTRODUCTION [2] The appellant was born in Z, Tigray, Ethiopia. In 1993, in order to avoid conscription into the Ethiopian army, he departed from Ethiopia with his stepmother after flying from Tigray to Addis Ababa and then travelling by truck to Nairobi, Kenya. Following an arranged marriage to a fellow Ethiopian who had been resettled into Australia, the appellant moved to Melbourne in May 1999. The marriage did not last. In 2003, he entered into a relationship with a New Zealand citizen, CC. Their daughter (AA) was born in New Zealand in February 2005. In May 2005, Immigration New Zealand (“INZ”) issued the appellant with a work visa to join CC on the basis of their relationship. He arrived in Dunedin in June 2005. CC and the appellant have since separated, reunited and separated again. They had a son (BB) in July 2009. The appellant had an industrial accident in May 2009 2 and subsequently his work permit was revoked by INZ. It appears he took no steps to obtain residence status on the basis of his relationships either in Australia or New Zealand. -

Ethiopians and Somalis Interviewed in Yemen

Greenland Iceland Finland Norway Sweden Estonia Latvia Denmark Lithuania Northern Ireland Canada Ireland United Belarus Kingdom Netherlands Poland Germany Belgium Czechia Ukraine Slovakia Russia Austria Switzerland Hungary Moldova France Slovenia Kazakhstan Croatia Romania Mongolia Bosnia and HerzegovinaSerbia Montenegro Bulgaria MMC East AfricaKosovo and Yemen 4Mi Snapshot - JuneGeorgia 2020 Macedonia Uzbekistan Kyrgyzstan Italy Albania Armenia Azerbaijan United States Ethiopians and Somalis Interviewed in Yemen North Portugal Greece Turkmenistan Tajikistan Korea Spain Turkey South The ‘Eastern Route’ is the mixed migration route from East Africa to the Gulf (through Overall, 60% of the respondents were from Ethiopia’s Oromia Region (n=76, 62 men and Korea Japan Yemen) and is the largest mixed migration route out of East Africa. An estimated 138,213 14Cyprus women). OromiaSyria Region is a highly populated region which hosts Ethiopia’s capital city refugees and migrants arrived in Yemen in 2019, and at least 29,643 reportedly arrived Addis Ababa.Lebanon Oromos face persecution in Ethiopia, and partner reports show that Oromos Iraq Afghanistan China Moroccobetween January and April 2020Tunisia. Ethiopians made up around 92% of the arrivals into typically make up the largest proportion of Ethiopians travelingIran through Yemen, where they Jordan Yemen in 2019 and Somalis around 8%. are particularly subject to abuse. The highest number of Somali respondents come from Israel Banadir Region (n=18), which some of the highest numbers of internally displaced people Every year, tensAlgeria of thousands of Ethiopians and Somalis travel through harsh terrain in in Africa. The capital city of Mogadishu isKuwait located in Banadir Region and areas around it Libya Egypt Nepal Djibouti and Puntland, Somalia to reach departure areas along the coastline where they host many displaced people seeking safety and jobs. -

From Falashas to Ethiopian Jews

FROM FALASHAS TO ETHIOPIAN JEWS: THE EXTERNAL INFLUENCES FOR CHANGE C. 1860-1960 BY DANIEL P. SUMMERFIELD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON (SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES) FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673074 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673074 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The arrival of a Protestant mission in Ethiopia during the 1850s marks a turning point in the history of the Falashas. Up until this point, they lived relatively isolated in the country, unaffected and unaware of the existence of world Jewry. Following this period and especially from the beginning of the twentieth century, the attention of certain Jewish individuals and organisations was drawn to the Falashas. This contact initiated a period of external interference which would ultimately transform the Falashas, an Ethiopian phenomenon, into Ethiopian Jews, whose culture, religion and identity became increasingly connected with that of world Jewry. It is the purpose of this thesis to examine the external influences that implemented and continued the process of transformation in Falasha society which culminated in their eventual emigration to Israel. -

Amhara Claim of Western and Southern Parts of Tigray

AMHARA CLAIM OF WESTERN AND SOUTHERN PARTS OF TIGRAY By Mathza 11-26-20 We have been hearing and reading about the Amhara Regional State claim of ownership of the Welqayit, Tsegede, Qafta-Humera and Tselemti weredas (hereafter refereed to Welqayit Group) and Raya, and Amhara Regional State threats of war against TPLF/Tigray. One of the threats states “some of the Amhara elite politicians continue to beat drums, as summons to war” (watch/listen) DW TV (Amharic) - July 30, 2020. THE WELQAYIT GROUP Welkayit Amhara Identity Committee (WAIC) was formed in Gonder to return the Welqayit Group from Tigray Regional State to Amhara Regional State. The Welqayit Group was transferred to Tigray during the 1984 reconfiguration of the administrative structure of the country based on ethno-linguistical regional states (kililoch) after the Derg was defeated. It seems that the government of Eritrea has contributed to the Welqayit Group problem. According to ህግደፍንኣሸበርቲ ጉጅለታትን ብአንደበት…ቀዳማይ ክፋል (watch) the Eritrean government had trained Ethiopian oppositions and inculcated opposing views between ethnic groups in Ethiopia, particularly between Amhara and Tigray Regional States, wherever it viewed appropriate for its devilish objective of dismantling Ethiopia. The Committee recruited Tigrayans from Tigray Regional State to do its dirty work. An example is presented in a video, Tigrai Tv:መድረኽተሃድሶ ወረዳ ቃፍታ- ሑመራህዝቢ ጣብያ ዓዲ-ሕርዲ - YouTube (watch) aired on Feb 01, 2017. It shows confessions by a number of Tigrayans from Qafta-Humera who were lured and bribed by the Committee to serve its objectives. Each of them gave details of activities they participated in and carried out against their own people. -

Local History of Ethiopia : Yirba Muda

Local History of Ethiopia Yirba Muda - Yuyu © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) yirba muda, damaged Nuxia tree? irba (O) 1. kind of small tree, Nuxia congesta; 2. stick for stirring food; muda (O) 1. defect, imperfection; 2. butter used for women's make up; mudda (O) girth, strap keeping a saddle or load on the back of an animal HCE83 Yirba Muda (Y. Mudda, Irba Moda, I. Muda, Yirba) 06/38 [Gz WO It Br] (Y. Moda, Irra Moda, Abba Muda) Gz: 06°12'/38°42' 2492 m; MS: 06°01'/38°43' = HCE63, 2597 m in Jemjem awraja, at 57 km from Kibre Mengist 1930s In an area inhabited by Jemjem and groups of Amhara. [Guida 1938] 1960s The primary school in 1968 had 106 boys and 24 girls in grades 1-4, with 3 teachers. In the 1970s with Norwegian mission station of the NLM. 1990s "There is at least one basic hotel (painted yellow). Irba Muda is ringed by cultivation, but it's all pristine forest and lush highland meadow beyond a radius of one kilometre or so." [Bradt 1995(1998)] HCE48 Yirbora, see Irbora HCD88 Yirega Cheffe, see Yirga Chefe yirga (A) "let it remain", royal decree allowing the holders to retain the land they already hold HFK14 Yirga 14°38'/37°55' 1347 m, near border of Eritrea 14/37 [Gz] yirga alem (A) "may the world stay as it is" HC... Yirga Alem, in Kefa awraja 07/36? [Ad] Sudan Interior Mission school in 1968 had 31 boys and 2 girls in grades 1-2, with two male teachers (Ethiopian). -

War in Tigray Ethiopia’S Test of Power

LAURENZ FÜRST War in Tigray Ethiopia’s Test of Power Abstract In November 2020, war broke out in Ethiopia’s northernmost province of Tigray. What started out as a struggle of a breakaway province soon turned into a full- scale war, pitting the Tigrayan Peoples Liberation Front against the Ethiopian central government. Not being able to crush the insurrection on its own, Ethiopia invited troops from neighbouring Eritrea and potentially even Somalia to put down the rebellion. When Abiy Ahmed assumed the office of Prime Minister of Ethiopia in April 2018, one thought that the winds of change had finally reached Ethiopia. It seemed that Ethiopia was able to perform the transition from an authoritarian one-party state to a Western- style democracy on the one hand and on the other hand be a force for stability and reconciliation in the Horn of Africa. FÜRST: WAR IN TIGRAY Table of contents Table of contents ................................................................................................................................1 Love thy neighbour or how war returned to the Horn of Africa ...........................................................2 Ex Africa semper aliquid novi ..............................................................................................................3 The Amhara expansion and the making and defending of modern Ethiopia ........................................4 Ityopya teqdam: the Amhara fortress under siege ..............................................................................6 1995 constitution: -

Conceptualizations and Impacts of Multiculturalism in the Ethiopian Education System

Conceptualizations and Impacts of Multiculturalism in the Ethiopian Education System by Fisseha Yacob Belay A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Fisseha Yacob Belay 2016 Conceptualizations and Impacts of Multiculturalism in the Ethiopian Education System Fisseha Yacob Belay Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This research, using critical qualitative research methods, explores the conceptualization and impact of multiculturalism within the Ethiopian education context. The essence of multiculturalism is to develop harmonious coexistence among people from diverse ethnic, social and cultural backgrounds. The current Ethiopian regime has used the ethnic federalism policy to restructure Ethiopia’s geopolitical, social and education policies along ethnic and linguistic lines. The official discourse of Ethiopian ethnic federalism and multicultural policies has emphasized the liberal values of diversity, tolerance, and recognition of minority groups. However, its application has resulted in negative ethnicity and social conflicts among different ethnic groups. Two universities, one in Oromia and another in Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s (SNNP) region, were selected using purposive sampling for this study. Document analysis and in-depth interviews were used to collect -

Wolqait Tegede RB Edited Version

1 Forceful Annexation, Violation of Human Rights and Silent genocide: A Quest for Identity and Geographic Restoration of Wolkait-Tegede, Gondar, Amhara, Ethiopia By: Achamyeleh Tamiru 1. Introduction Ethiopian history has been studied and written by both foreign and local scholars for many centuries. Some of the writers were purely scholars while others were travelers documenting their trip experiences. These writers have extensively defined the boundaries of the many administrations, languages, cultures, traditions, faiths and other characteristics of Ethiopia. These factual documentations were especially true of Northern Ethiopia. It's also essential to note that these historical documentations were done in several European languages as well as Amharic and Geez. One of the many areas described by writers ever since the 14th century is the area surrounding the Tekeze River and the people of Ethiopia on both sides of the 4th largest river in Ethiopia. One of the notable regions and the interest of this article is the locality and the people of Wolkait-Tegede in historical Gondar, Ethiopia. Historical documents and maps dated from about 1434 to 1991 show that Wolkait-Tegede were pars of the Gondar province of Amhara. Despite the availability of a mountain of evidence to support this fact however, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) has annexed the Wolkait-Tegede region into historical Tigray region in 1991. In fact during its bush days, it was in 1979 when TPLF entered Wolkait-Tegede and declared the land as part of its newly coming “Greater Republic of Tigray”. In other words, to bring it to today's Ethiopian reality, a region in Amhara Federal State is transferred to Tigray Federal State by force.