Trade in Molluskan Religiofauna Between the Southwe Stern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavin-Report-1999-08

AUGUST 16, 1999 ISSUE 2268 TOE MOST TRUSTED NAME IN RADIO tH.III'-1111; melissa etheridge And Now... angels would fall The Boulder Summit MUSIC TOP 40 Enrique Dances Into Top 10 HOT AIC There Goes Sixpence...Again AIC Clapton's "Blue Eyes" Wide Open COUNTRY impacting radio august 25th Chely Is Wright for #1 NEWS GAVIN Hits With HyperACTIVE Artemis Announces Promo Team From the Publishers of Music Week, MI and tono A Miller Freeman Publication www.americanradiohistory.com advantage Giving PDs the Programming Advantage Ratings Softwaiv designed dust for PDs! Know Your Listeners Better Than Ever with New Programming Software from Arbitron Developed with input from PDs nationwide, PD Advantage'" gives you an "up close and personal" look at listeners and competitors you won't find anywhere else. PD Advantage delivers the audience analysis tools most requested by program directors, including: What are diarykeepers writing about stations in my market? A mini -focus group of real diarykeepers right on your PC. See what listeners are saying in their diary about you and the competition! When listeners leave a station, what stations do they go to? See what stations your drive time audience listens to during midday. How are stations trending by specific age? Track how many diaries and quarter -hours your station has by specific age. How's my station trending hour by hour? Pinpoint your station's best and worst hours at home, at work, in car. More How often do my listeners tune in and how long do (c coue,r grad they stay? róathr..,2 ,.,, , Breaks down Time Spent Listening by occasions and TSL per occasion. -

City in the Sand Ebook

CITY IN THE SAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Chubb | 213 pages | 29 Jan 2000 | Libri Publications Ltd | 9781901965025 | English | London, United Kingdom City in the Sand PDF Book Guests staying in any of The Castle accommodations will find The Castle is the perfect beachfront and oceanfront location. That has to be rare indeed. Open Preview See a Problem? I thought was an excellent addition to the main book. If the artifacts are indeed prehistoric stone tools, then it means humans settled on the shores of ancient Pleistocene lake more than 30, years ago. The well was the only permanent watering place in those parts and, being a necessary watering place for Bedouin raiders, had been the scene of many fierce encounters in the past, [12]. According to those overseeing the project, Neom has already invited tenders from a range of international firms, while plans are moving forward to build a road bridge to Egypt. In the valley of the Tombs, to the east of the city, the "houses of the dead," veritable underground palaces, were decorated with particularly fine sculpture and frescoes. Most tales of the lost city locate it somewhere in the Rub' al Khali desert, also known as the Empty Quarter, a vast area of sand dunes covering most of the southern third of the Arabian Peninsula , including most of Saudi Arabia and parts of Oman , the United Arab Emirates , and Yemen. Biotech City of the Future Healthcare. Original Title. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Emir Fakhr ad-Din was still using Palmyra as a place to exercise his police, however he was anxious to have greater security than offered by the ruined city, so he had a castle built on the hillside overlooking it. -

People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: a Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2012 People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Deborah Confer University of Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, Douglas and Confer, Deborah, "People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada" (2012). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 98. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/98 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series National Park Service Publication Number 2012-01 U.S. Department of the Interior PEOPLE OF SNOWY MOUNTAIN, PEOPLE OF THE RIVER: A MULTI-AGENCY ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND COMPENDIUM RELATING TO TRIBES ASSOCIATED WITH CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA 2012 Douglas Deur, Ph.D. and Deborah Confer LAKE MEAD AND BLACK CANYON Doc Searls Photo, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons -

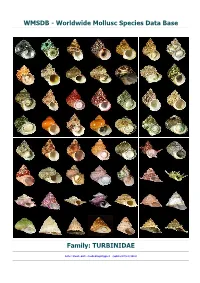

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Moluscos

A Chave Os nomes galegos dos moluscos 2017 Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (2017): Nomes galegos dos moluscos recomendados pola Chave. http://www.achave.gal/wp-content/uploads/achave_osnomesgalegosdos_moluscos.pdf 1 Notas introdutorias O que contén este documento Neste documento fornécense denominacións para as especies de moluscos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algunhas das especies exóticas máis coñecidas (xeralmente no ámbito divulgativo, por causa do seu interese científico ou económico, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas). En total, achéganse nomes galegos para 534 especies de moluscos. A estrutura En primeiro lugar preséntase unha clasificación taxonómica que considera as clases, ordes, superfamilias e familias de moluscos. Aquí apúntase, de maneira xeral, os nomes dos moluscos que hai en cada familia. A seguir vén o corpo do documento, onde se indica, especie por especie, alén do nome científico, os nomes galegos e ingleses de cada molusco (nalgún caso, tamén, o nome xenérico para un grupo deles). Ao final inclúese unha listaxe de referencias bibliográficas que foron utilizadas para a elaboración do presente documento. Nalgunhas desas referencias recolléronse ou propuxéronse nomes galegos para os moluscos, quer xenéricos quer específicos. Outras referencias achegan nomes para os moluscos noutras linguas, que tamén foron tidos en conta. Alén diso, inclúense algunhas fontes básicas a respecto da metodoloxía e dos criterios terminolóxicos empregados. 2 Tratamento terminolóxico De modo moi resumido, traballouse nas seguintes liñas e cos seguintes criterios: En primeiro lugar, aprofundouse no acervo lingüístico galego. A respecto dos nomes dos moluscos, a lingua galega é riquísima e dispomos dunha chea de nomes, tanto específicos (que designan un único animal) como xenéricos (que designan varios animais parecidos). -

Download Download

Appendix C: An Analysis of Three Shellfish Assemblages from Tsʼishaa, Site DfSi-16 (204T), Benson Island, Pacific Rim National Park Reserve of Canada by Ian D. Sumpter Cultural Resource Services, Western Canada Service Centre, Parks Canada Agency, Victoria, B.C. Introduction column sampling, plus a second shell data collect- ing method, hand-collection/screen sampling, were This report describes and analyzes marine shellfish used to recover seven shellfish data sets for investi- recovered from three archaeological excavation gating the siteʼs invertebrate materials. The analysis units at the Tseshaht village of Tsʼishaa (DfSi-16). reported here focuses on three column assemblages The mollusc materials were collected from two collected by the researcher during the 1999 (Unit different areas investigated in 1999 and 2001. The S14–16/W25–27) and 2001 (Units S56–57/W50– source areas are located within the village proper 52, S62–64/W62–64) excavations only. and on an elevated landform positioned behind the village. The two areas contain stratified cultural Procedures and Methods of Quantification and deposits dating to the late and middle Holocene Identification periods, respectively. With an emphasis on mollusc species identifica- The primary purpose of collecting and examining tion and quantification, this preliminary analysis the Tsʼishaa shellfish remains was to sample, iden- examines discarded shellfood remains that were tify, and quantify the marine invertebrate species collected and processed by the site occupants for each major stratigraphic layer. Sets of quantita- for approximately 5,000 years. The data, when tive information were compiled through out the reviewed together with the recovered vertebrate analysis in order to accomplish these objectives. -

11. References

11. References Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT). State Transportation Improvement Program. December 1994. Associated Cultural Resource Experts (ACRE). Boulder City/U.S. 93 Corridor Study Historic Structures Survey. Vol. 1: Final Report. September 2002. _______________. Boulder City/U.S. 93 Corridor Study Historic Structures Survey. Vol. 1: Technical Report. July 2001. Averett, Walter. Directory of Southern Nevada Place Names. Las Vegas. 1963. Bedwell, S. F. Fort Rock Basin: Prehistory and Environment. University of Oregon Books, Eugene, Oregon. 1973. _______________. Prehistory and Environment of the Pluvial Fort Rock Lake Area of South Central Oregon. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon, Eugene. 1970. Bernard, Mary. Boulder Beach Utility Line Installation. LAME 79C. 1979. Bettinger, Robert L. and Martin A. Baumhoff. The Numic Spread: Great Basin Cultures in Competition. American Antiquity 46(3):485-503. 1982. Blair, Lynda M. An Evaluation of Eighteen Historic Transmission Line Systems That Originate From Hoover Dam, Clark County, Nevada. Harry Reid Center for Environmental Studies, Marjorie Barrick Museum of Natural History, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. 1994. _______________. A New Interpretation of Archaeological Features in the California Wash Region of Southern Nevada. M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. 1986. _______________. Virgin Anasazi Turquoise Extraction and Trade. Paper presented at the 1985 Arizona-Nevada Academy of Sciences, Las Vegas, Nevada. 1985. Blair, Lynda M. and Megan Fuller-Murillo. Rock Circles of Southern Nevada and Adjacent Portions of the Mojave Desert. Harry Reid Center for Environmental Studies, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. HRC Report 2-1-29. 1997. Blair, Lynda M. -

F Scott Fitzgerald's New York

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 His Lost City: F Scott Fitzgerald's New York Kris Robert Murphy College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Murphy, Kris Robert, "His Lost City: F Scott Fitzgerald's New York" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625818. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-zdpj-yf53 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIS LOST CITY: F. SCOTT FITZGERALD’S NEW YORK A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Kris R. Murphy 1993 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, July 1993 Scott Donaldson Christopher MacGowan Robert Maccubbin TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............................................................................................iv ABSTRACT.............................................................................. ...................................... v CHAPTER I. ‘The far away East. .the vast, breathless bustle of New York”. 3 CHAPTER II. “Trips to New York” (1907-1918)........................................................ 11 CHAPTER III. ‘The land of ambition and success” (1919-1920) ................................ 25 CHAPTER IV. ‘The great city of the conquering people” (1920-1921)...................... 53 CHAPTER V. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

Intertidal Organisms of Point Reyes National Seashore

Intertidal Organisms of Point Reyes National Seashore PORIFERA: sea sponges. CRUSTACEANS: barnacles, shrimp, crabs, and allies. CNIDERIANS: sea anemones and allies. MOLLUSKS : abalones, limpets, snails, BRYOZOANS: moss animals. clams, nudibranchs, chitons, and octopi. ECHINODERMS: sea stars, sea cucumbers, MARINE WORMS: flatworms, ribbon brittle stars, sea urchins. worms, peanut worms, segmented worms. UROCHORDATES: tunicates. Genus/Species Common Name Porifera Prosuberites spp. Cork sponge Leucosolenia eleanor Calcareous sponge Leucilla nuttingi Little white sponge Aplysilla glacialis Karatose sponge Lissodendoryx spp. Skunk sponge Ophlitaspongia pennata Red star sponge Haliclona spp. Purple haliclona Leuconia heathi Sharp-spined leuconia Cliona celata Yellow-boring sponge Plocarnia karykina Red encrusting sponge Hymeniacidon spp. Yellow nipple sponge Polymastia pachymastia Polymastia Cniderians Tubularia marina Tubularia hydroid Garveia annulata Orange-colored hydroid Ovelia spp. Obelia Sertularia spp. Sertularia Abientinaria greenii Green's bushy hydroid Aglaophenia struthionides Giant ostrich-plume hydroid Aglaophenia latirostris Dainty ostrich-plume hydroid Plumularia spp. Plumularia Pleurobrachia bachei Cat's eye Polyorchis spp. Bell-shaped jellyfish Chrysaora melanaster Striped jellyfish Velella velella By-the-wind-sailor Aurelia auria Moon jelly Epiactus prolifera Proliferating anemone Anthopleura xanthogrammica Giant green anemone Anthopleura artemissia Aggregated anemone Anthopleura elegantissima Burrowing anemone Tealia lofotensis -

Spagnuolo.Pdf

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL ESTABLISHING A TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION FOR CERAMICS OF THE WASHINGTON COUNTY, UT VIRGIN RIVER BRANCH OF THE ANCESTRAL PUEBLOAN Crystal Spagnuolo (Dr. Brian Codding; Kenneth Blake Vernon, MA) Department of Anthropology Dating archaeological sites is important for establishing patterns in settlement, trade, resource use, and population estimates of prehistoric peoples. Using dated sites, we can see patterns in how a culture such as the Ancestral Puebloan went from a foraging subsistence to agricultural settlements with far-reaching trade networks. Or, we can understand when the Ancestral Puebloan abandoned certain areas of the American Southwest and pair this with climate data to understand how climate might be a factor. In order to do so however, we must first have a reliable timeline of these events, built from archaeological sites that are reliably dated. Unfortunately, direct dating via radiocarbon or dendrochronology is costly and not always possible due to the biodegradable nature of the organic materials needed for such dating. Using a relative dating system that employs ceramics is a cost-effective alternative. Here I continue work begun by The Archaeological Center at the University of Utah to generate a ceramic dating system for the area encompassing Southwest Utah, focusing on Washington County, using extant site data from this region. While the prehistoric inhabitants of this area were Ancestral Puebloan, the ceramic traditions were separate, and therefore merit their own dating analysis (Lyneis, 1995; Spangler, Yaworsky, Vernon, & Codding, 2019). Currently, dating of sites in the region is difficult, both due to the expense of direct dating techniques (radiocarbon and dendrochronology) and the lack of defined time periods for ceramics types. -

Karen G. Harry

Karen G. Harry Department of Anthropology University of Nevada Las Vegas 4505 Maryland Parkway, Box 45003 Las Vegas, NV 89154-5003 (702) 895-2534; [email protected] Professional Employment 2014-present Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada Las Vegas 2007-2014 Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada Las Vegas 2001-2007 Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada Las Vegas 1997-2001 Director of Cultural Resources, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin 1997 Adjunct Faculty, Pima Community College, Tucson 1990-1996 Project Director, Statistical Research, Inc., Tucson Education 1997 Ph.D., University of Arizona, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona 1987 M.A., Anthropology, University of Arizona 1982 B.A., Anthropology, Texas A&M University, cum laude Research Interests Southwestern archaeology; ceramic analysis, sourcing, and technology; organization of craft production; trade and exchange issues; chemical compositional analysis; prehistoric leadership strategies; prehistoric community organization Ongoing Field Projects Field Research on the Parashant National Monument: I am involved in a long-term archaeological research project concerning the Puebloan occupation of the Mt. Dellenbaugh area of the Shivwits Plateau, located within Parashant National Monument. Field and Archival Research in the Lower Moapa Valley: A second area of ongoing research involves the Puebloan occupation of the lower Moapa Valley of southern Nevada. I have recently completed an archival study of the artifacts and records associated with the early (1920s-1940s) field research of this area, and have on-going field investigations in the area. updated Sept. 1 , 2020 Books & Special Issues of Journals 2019 Harry, Karen G. and Sachiko Sakai (guest editors).