On the Threshold Paul Scott, New American Scenery. Liminal Entities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No

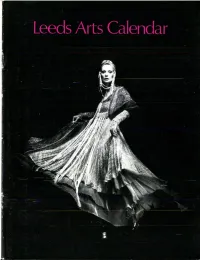

I LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED !>t;>rtin>»»ith thr f>rst issue publ>shed >n l947, thc cntin I ii ii) »fili Calindar is now availabl< on mi< ro- film. I'>'rit( I'(>r inl<)rmati<)n <>r scud ord('rs dirc( t t<): I 'nivrrsi< < .'>If< rolilms. Inc., 300:)I /r< h Ro»d, i><nn Arbor, Xfichit,an 4II f06, bhS.A. Leeds Art Collections Fund 'I'h>s >( i>i»tppri>l t(i all 'w'h(l;n'('nt('>'('sll'd it> th< A> ts. 'I'h< I.«ds Art Coll<« >ious Fund is tl>< s<)u>'(( <if''( t uhi> I'undo f()r huff«>» works of'rt Ii)r th< I.r<do (<)ilia ti(in. 0'< >(a>n< ni<ir< subscribing incmbcrs to Siv< / a or upwards ra< h >car. I't'hy not id('n>il'I yours( If with th('>'t (»><if('>') and I cn>f)l(. c'wsan»: '('c('>v('ol«' Ilti Cilli'lliliii''('(', >'<'('<'>>'('nv>tat«)i>s to I'un< Co< er: all ti<ins, privati > i< ws;in<I <irt»;>nis«I visits tu f)lt>('('s of'nt('n Dre)> by f3ill G'ibb, til7B Ilu «ater/i>It deroration im thi s>. In writin>» l<>r an appli( a>i<i>i fi>r»i Io (h(. die» ii hy dli ion Combe, lhe hat by Diane Logan for Bill Hr»n I ii'<i )i(im. l ..II..I inol<l E)»t.. Butt()le)'tii'i't. I i'eili IO 6'i bb, the shoe> by Chelsea Cobbler for Bill Gibb. -

Staffordshire Pottery and Its History

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Toronto http://archive.org/details/staffordshirepotOOwedg STAFFORDSHIRE POTTERY AND ITS HISTORY STAFFORDSHIRE POTTERY AND ITS HISTORY By JOSIAH C. WEDGWOOD, M.P., C.C. Hon. Sec. of the William Salt Archaeological Society. LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & CO. LTD. kon Si 710620 DEDICATED TO MY CONSTITUENTS, WHO DO THE WORK CONTENTS Chapter I. The Creation of the Potteries. II. A Peasant Industry. III. Elersand Art. IV. The Salt Glaze Potters. V. The Beginning of the Factory. VI. Wedgwood and Cream Colour. VII. The End of the Eighteenth Century. VIII. Spode and Blue Printing. IX. Methodism and the Capitalists. X. Steam Power and Strikes. XI. Minton Tiles and China. XII. Modern Men and Methods. vy PREFACE THIS account of the potting industry in North Staffordshire will be of interest chiefly to the people of North Stafford- shire. They and their fathers before them have grown up with, lived with, made and developed the English pottery trade. The pot-bank and the shard ruck are, to them, as familiar, and as full of old associations, as the cowshed to the countryman or the nets along the links to the fishing popula- tion. To them any history of the development of their industry will be welcome. But potting is such a specialized industry, so confined to and associated with North Stafford- shire, that it is possible to study very clearly in the case of this industry the cause of its localization, and its gradual change from a home to a factory business. -

DAACS Cataloging Manual: Ceramics

DAACS Cataloging Manual: Ceramics by Jennifer Aultman, Nick Bon-Harper, Leslie Cooper, Jillian Galle, Kate Grillo, and Karen Smith OCTOBER 2003 LAST UPDATED OCTOBER 2014 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 6 1. CERAMIC ARTIFACT ENTRY ...................................................................................... 7 1.1 COUNT ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 WARE .......................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 MATERIAL ..................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 MANUFACTURING TECHNIQUE .......................................................................................... 9 1.5 VESSEL CATEGORY .......................................................................................................... 9 1.6 FORM ......................................................................................................................... 10 1.6.1 Teaware ............................................................................................................ 10 1.6.2 Tableware ......................................................................................................... 11 1.6.3 Utilitarian ......................................................................................................... -

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Walter Collection

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Walter Collection http://www.nmm.ac.uk/collections/explore/object. .................. cfm?ID=AAA4725 Jug, ................... Unknown Jug, Date unknown John Turner Stoneware 1805 Overall: 132 x 120 x 107 mm Lane End, Longton, Staffordshire, England National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Stoneware Greenwich Hospital Collection Overall: 203 x 127 x 140 mm Reputedly the favourite grog jug of Vice-Admiral Owned by Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758-1805). Horatio Nelson (1758-1805). It was presented to The white, salt-glazed stoneware jug has a cane- Greenwich Hospital by the widow of George Potts, ribbed base and a brown neck and handle terminat- MP for Barnstable, Devon in 1890. A white, salt- ing in acanthus leaves. It has applied decoration of glazed stoneware jug with the upper part and the top cherubs and vine leaves and has been mounted with a of the handle glazed brown. The base is fluted and silver rim and a lid engraved with the Hardy crest of above the fluting are applied reliefs of Venus and Cu- a wyvern’s head. The mount is hallmarked 1805 and pid with plants and trees. The neck is reeded and the is inscribed ‘This mug originally belonged to Lord handle has an acanthus leaf termination. The relief of Viscount Nelson was presented to Capt Mackellar by Venus and Cupid entitled ‘Sportive Love’ was de- Sir Thos. Hardy Bart.’ rived from an antique fragment, once at the Florentine Museum, interpreted by Elizabeth Lady Templetown * Our jug is identical in size, finish but with a differ- and modelled by William Hackwood circa 1783 for ent silver mount and no lid. -

Josiah Wedgwood, F.R.S., His Personal History

I JOSIAH WEDGWOOD, F.R.S. HIS PEKSONAL HISTOEY BY SAMUEL gMILES, LL.D. AUTHOR OP "SELF-HELP" "CHARACTER" "THRIFT" ETC, Never hasting, never resting, With a firm and joyous heart, Ever onward slowly tending, Acting, aye, a brave man's part. Undepressed by seeming failure. Unelated by success,' Heights attained, revealing higher, Onward, upward, ever press. NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS 1895 Copyright, 1894, by HARPER & BROTHERS. All rights reserved. Wio 710775 CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE I. JOSIAH WEDGWOOD BIRTH AND EDUCA- TION 1 II. THE WEDGWOOD FAMILY . .... 7 III. JOSIAH WEDGWOOD LEARNS HIS TRADE . 21 IV. PARTNERSHIPS WITH HARRISON AND WHIEL- DON 33 V. WEDGWOOD BEGINS BUSINESS FOR HIMSELF 42 VI. IMPROVEMENT OF WARE FRIENDSHIP WITH BENTLEY 57 vii. WEDGWOOD'S MARRIAGE 68 VIII. WEDGWOOD APPOINTED QUEEN'S POTTER . 76 IX. FOUNDING OF ETRURIA PARTNERSHIP WITH BENTLEY 89 */X. ROADS AND CANALS THROUGH STAFFORD- SHIRE 96 J" XI. IMPROVEMENT OF MODELS CHEMISTRY . Ill XII. AMPUTATION OF WEDGWOOD'S RIGHT LEG . 125 J xin. WEDGWOOD'S ARTISTIC WORK .... 137 XIV. PORTRAITS MEDALLIONS ARTISTIC WORK 158 XV. GROWAN KAOLIN BOTTGHER COOK- WORTHYMANUFACTURE OF PORCELAIN 179 xvi. WEDGWOOD'S JOURNEY INTO CORNWALL . 193 XVH. WEDGWOOD AND FLAXMAN 210 iv Contents CHAP. PAGE XVIII. WEDGWOOD AT WORK AGAIN DEATH OF BENTLEY 247 xix. WEDGWOOD'S PYROMETER OR THERMOM- ETER 264 XX. THE BARBERINI OR PORTLAND VASE . 282 xxi. WEDGWOOD'S PERSONAL HISTORY HIS SONS' EDUCATION 297 XXII. CHARACTER OF WEDGWOOD 315 JOSIAH WEDGWOOD CHAPTER I JOSIAH WEDGWOOD BIRTH AND EDUCATION JOSIAH WEDGWOOD was born in the house adjoining the Churchyard Works at Burslem, Staffordshire, in 1730. -

The Potter Thomas Whieldon the Potter Thomas Whieldon

The Potter Thomas Whieldon Ulrich Alster Klug, 2009, [email protected] Thomas Whieldon was baptized Sep. 9th. 1719 in the church in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England as the son of Joseph Whieldon and wife Alcia (Alice), see . The trade of his father is unknown, but it is most likely that Joseph Whieldon was a potter of mayby had work connected with the potting industry. Joseph died in 1731, when Thomas was 11 years old. His mother had already died in 1726. Figur 1: Minature of Ths. Figur 2: The Whieldon Whieldon, which was sold at coat of arms, with the auction by the widow of his It is unknown to whom Thomas as apprenticed, but it is Staffordshire Lion, the grand-son, John Bill parrott and pears. - As Whieldon, in 1908, London. possible that he was raised by a family member who used by G. Whieldon of was a potter and therefore apprenticed to him. Springfield House. The master potter - only 21 years old In 1740, only 21 years old, he is mentioned as a master potter in Fenton Low. He was the partner of John Astbury, a leading potter of this time. In 1747 he leased new premises at Fenton Vivian, bought this property in 1748 and the following year acquired Fenton Hall. By this time he is known to have had 19 employees. He worked though out his entire active period, which lasted until 1780, with both different clays and glazes. He is known for his agate ware, his tortoise-shell glazes and colourful figures. He made almost every possible item in pottery, both handles for knives and forks, tea pots, punch pots, cups, plates, saucers, cream cows, figures i.e. -

Laboratory Reference Book 2010

Alexandria Archaeology Laboratory Reference Book Lexicon and Illustrated Glossary Photo by Gavin Ashworth, Courtesy Ceramics in America Revised June 2010 Barbara H. Magid Alexandria Archaeology Laboratory Reference Book Revised June 2010 Barbara H. Magid © City of Alexandria, Virginia June 2010 1 2 Alexandria Archaeology Laboratory Reference Book TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................................................5 LEXICON CERAMICS General instructions......................................................................…………..........................................7 Ware.................................................................…………..........................................9 Type.........................................................................................................10 Variety...........................................................................................................................................11 Function......................................................................................................................12-13 GLASS General instructions.......................................................................................................................15 Type or Color .......................................................................................................................................17 Function ............................................................................................................................18 -

A Plated Article

PR ^511 A PLATED ARTICLE by Charles Dickens CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY , ""'™rai'y Library PR 4572 pt""'" an ')\Smmimm'^-^'*^ introductory i 3 1924 013 473 123 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013473123 Josiah Spode A Plated Article CHARLES DICKENS With an Introductory Account of the Historical Spode-Copeland China Works to which it refers "^ W. T. COPELAND & SONS (lateSpode & Copdani) STOKE- UPON-TRENT Spode THE home beautiful began with pottery. Natural beauty always existed, but it was the potter who first expressed man's ap- preciation of it by trying to give grace of form and charm of colour to the rude vessels used in the home life of primitive days. The jars in which primeval man stored his grain for the winter months were moulded by his bare hands on a boulder, rudely decorated, and dried in the sim. It was not long, however, before man discovered the magic power that fire has of transforming the soft clay into a hard substance ; the potter's wheel was also the chief out- come of his experiments. Thus the kiln and the wheel were both known to all ancient civilizations, and were the essential factors in the making of pot- tery from the earliest times to the present day. Although EngUsh pottery did not achieve any im- portance until the eighteenth century, this country can congratulate itself on possessing a race of potters unsurpassed in the world. -

Daacswaredescription Waretypes BEGINDATE ENDDATE Afro

DAACSWareDescription WareTypes BEGINDATE ENDDATE Afro-Caribbean Ware AfroCaribWare Does Not Contribute to MCD Does Not Contribute to MCD Agate, refined (Whieldon-type) AgateRefined 1740 1775 Albemarle Series Quartz Temper AlbemarleQuartzTemper Does Not Contribute to MCD Does Not Contribute to MCD American Stoneware AmericanStoneware 1750 1920 Astbury-Type AstburyType 1725 1775 Bennington/Rockingham BenningtonRockingham 1830 1900 Black Basalt BlackBasalt 1750 1820 British Stoneware BritishStoneware 1671 1800 Buckley Buckley 1720 1775 Burslem Burslem 1700 1725 Canary Ware CanaryWare 1780 1835 Carolina' Creamware Carolina Creamware 1765 1775 Cauliflower ware Cauliflowerware 1760 1780 Coarse Earthenware, Jamaican CEWJamaican Does Not Contribute to MCD Does Not Contribute to MCD Coarse Earthenware, unidentified CoarseEarthenwareUnid Does Not Contribute to MCD Does Not Contribute to MCD Colonoware Colonoware 1650 1830 Creamware Creamware 1762 1820 Delftware, Dutch/British Delft 1600 1802 Derbyshire Derbyshire 1750 1800 Elers Ware ElersWare 1690 1750 Faience Faience 1700 1800 Frechen Brown FrechenBrown 1600 1800 Fulham Type FulhamType 1671 1775 German Stoneware GermanStoneware 1620 1775 Iberian Ware IberianWare 1600 1780 Ironstone/White Granite IronstoneWhiteGranite 1840 2000 Jackfield Type Jackfield 1740 1790 Jasperware Jasperware 1774 2000 Native American, unid. NativeAmericanUnid Does Not Contribute to MCD Does Not Contribute to MCD North Devon Gravel Tempered NorthDevonGravel 1600 1775 North Devon Plain NorthDevonPlain 1600 1710 Nottingham -

Newsletter and Web Site So Please Check on a Regular Basis

NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY (MIDLANDS ANCESTORS) March Quarter 2021 EE NNeewwsslleetttteerr Happy new year to you all, Let’s hope that 2021 will be a better year For the foreseeable future there will be no meetings due to coronavirus. We will communicate any change via the newsletter and web site so please check on a regular basis. The newsletter will be added to the web page on the following dates for you to view: 31st March 2021 30th June 2021 30th September 2021 31st December 2021 More and more churches and chapels are being lost or turned into restaurants or residential properties so this begs the question where do the memorials go? Are they taken to the mother church? Are they left with the property ? Are they dumped into a skip? Can you spare a little time to photograph the memorial located inside churches, chapels etc. If you feel you can help please email me and I will let you know which churches/chapels need to have their memorials photographed near you. [email protected] Search passenger arrivals into Australia by going to the national archives of Australia http://recordsearch.naa.gov.au Search passenger arrivals into New Zealand www.archway.archives.govt.nzw Search for passengers who have journeyed to British Guiana see www.theshipslist.com/ships/passengerlists https://www.microsoft.com/ftanalyzer The FREE FTAnalyzer allows you to load a GEDCOM file of your tree and shows you lots of new ways of looking at your data. You can use it to identify and fix duplicates and other errors, ex- port various reports to excel, view your family on a map, see research suggestions showing missing data and double click to automatically search your favourite family history website (Ancestry/FindMyPast/FamilySearch/FreeCen/ScotlandsPeople) and lots more. -

The Earthenware Collector Uniform with This Volume

THE EARTHENWARE COLLECTOR UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME THE FURNITURE COLLECTOR THE GLASS COLLECTOR THE CHINA COLLECTOR THE STAMP COLLECTOR THE SILVER AND SHEFFIELD PLATE COLLECTOR " I, WiNCANTON Jug. Nathaniel Ireson, 1748." Glaisher Collection, THE EARTHENWARE COLLECTOR BY G. WOOLLISCROFT RHEAD WITH SIXTY ILLUSTRATIONS IN HALF-TONE AND NUMEROUS MARKS NEW YORK DODD, MEAD & COMPANY 1920 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner, Frome and London ; FOREWORD BY THE EDITOR. old as civilisation itself, the art of the potter AS presents a kaleidoscope of alluring charm. To paraphrase the word of Alexandre Brongniart, no branch of industry, viewed in reference either to its history or its theory, or its practice, offers more that is interesting and fascinating, regarding alike its economic appUcation and its artistic aspect, than does the fictile art ; nor exhibits products more simple, "more varied, and their frailty notwithstanding, more desirable. Of course the crude vessels of ancient times, as well as the more serviceable and scientifically more beauti- ful articles of to-day, exist primarily for one and the same object—the use and convenience of man. The story of the potter and his technique has been told repeatedly, sometimes as a general survey and some- times as a specialised branch of a widely extended subject, but notwithstanding the numerous books devoted to it there is always something new to be recorded, fresh pieces to describe, new points to advance and discuss. In these respects The Earthenware Collector will serve the twofold purpose of explaining clearly and concisely the various English wares and how to identify them FOREWORD and of relating the potter's life and the manifold difficulties that he has constantly to overcome ; for some of these men, with little knowledge of their craft, were yet adventurers, as the Elizabethan voyagersr were, saiHng into unknown seas in quest of discovery and fortune ! Mr. -

Newbigging Pottery, Musselburgh: Ceramic Resource Disk Introduction and Acknowledgments

1 Newbigging Pottery, Musselburgh: Ceramic Resource Disk Introduction and Acknowledgments Introduction The Newbigging ceramic material, listed and photographed on the enclosed disk has been assigned to the National Museums of Scotland and was catalogued using accession numbers (FD 2004.1.1 to 507. This small and fairly commonplace ceramic assemblage derives from a pottery of 19th and early 20th century date. The shards have been divided by fabric type, form and decoration into 6 folders and 58 files. The majority of the pottery was recovered during a small rescue excavation and salvage operation funded by Historic Scotland. Most of the on site work was carried out by Alison McIntyre, Alan Radley and the author over a three week period at the end of December 1987 and beginning of January 1988. While carrying out research for a paper on archaeologically derived French pottery in Scotland, I visited a number of Scottish Museums holding shard collections. To my dismay, I found that the majority were storing their ceramic material in a way that makes studying them very difficult and extremely time consuming. It was with these problems in mind, that I decided while preparing my industrial pottery for archive, to produce a number of resource disks as a means of getting all my shard evidence for Scottish east coast potteries into the public domain. These disks are not intended to be ‘publications’ in the accepted sense and should not be seen as such. They are no more than tools for future research. 2 The four hundred plus photographs on the Newbigging resource disk were taken against a one cm square background in the NMS ceramic storeroom, and are certainly not of publication standard.