Wedgwood, Innovation and Patent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Patent Law: a Handbook for Congress

Patent Law: A Handbook for Congress September 16, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46525 SUMMARY R46525 Patent Law: A Handbook for Congress September 16, 2020 A patent gives its owner the exclusive right to make, use, import, sell, or offer for sale the invention covered by the patent. The patent system has long been viewed as important to Kevin T. Richards encouraging American innovation by providing an incentive for inventors to create. Without a Legislative Attorney patent system, the reasoning goes, there would be little incentive for invention because anyone could freely copy the inventor’s innovation. Congressional action in recent years has underscored the importance of the patent system, including a major revision to the patent laws in 2011 in the form of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act. Congress has also demonstrated an interest in patents and pharmaceutical pricing; the types of inventions that may be patented (also referred to as “patentable subject matter”); and the potential impact of patents on a vaccine for COVID-19. As patent law continues to be an area of congressional interest, this report provides background and descriptions of several key patent law doctrines. The report first describes the various parts of a patent, including the specification (which describes the invention) and the claims (which set out the legal boundaries of the patent owner’s exclusive rights). Next, the report provides detail on the basic doctrines governing patentability, enforcement, and patent validity. For patentability, the report details the various requirements that must be met before a patent is allowed to issue. -

Fabrication Porcelain Slabs

BASIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FABRICATING WALKER ZANGER’S SECOLO PORCELAIN SLABS CNC Bridge Saw Cutting Parameters: • Make certain the porcelain slab is completely supported on the flat, level, stable, and thoroughly cleaned bridge saw cutting table. • Use a Segmented Blade - Diameter 400 mm @ 1600 RPM @ 36” /min. We recommend an ADI MTJ64002 - Suitable for straight and 45-degree cuts. • Adjust the water feed directly to where the blade contacts the slab. • Before the fabrication starts, it is important to trim 3/4” from the slab’s four edges to remove any possible stress tension that may be within the slab. (Figure 1 on next page) • Reduce feed rate to 18”/min for the first and last 7” for starting and finishing the cut over the full length of the slab being fabricated. (Figure 2 on next page) • For 45-degree edge cuts reduce feed rate to 24” /min. • Drill sink corners with a 3/8” core bit at 4500 RPM and depth 3/4” /min. • Cut a secondary center sink cut 3” inside the finish cut & remove that center piece first, followed by removing the four 3” strips just inside the new sink edge. (Figure 3 on next page) • Keep at least 2” of distance between the perimeter of the cut-out and the edge of the countertop. • Use Tenax Enhancer Ager to soften the white vertical porcelain edge for under mount sink applications. • For Statuary, Calacata Gold, and Calacata Classic slabs bond mitered edge detail with Tenax Powewrbond in the color Paper White. (Interior & Exterior Applications - Two week lead time) • Some applications may require a supporting backer board material to be adhered to the backs of the slabs. -

Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G

Wonders of Nature and Artifice Art and Art History Fall 2017 Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G. Waters '19, Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Waters, Laura G., "Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate" (2017). Wonders of Nature and Artifice. 12. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Abstract This authentic Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) plate is a prime example of early export porcelain, a luminous substance that enthralled European collectors. The eg nerous gift of oJ yce P. Bishop in honor of her daughter, Kimberly Bishop Connors, Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Plate is on loan from the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The lp ate itself is approximately 7.75 inches (20 cm) in diameter, and appears much deeper from the bottom than it does from the top. -

PORCELAIN TILE PORCELAIN TILE INDEX Moodboard .02 Color Palette .03 Colors & Sizes

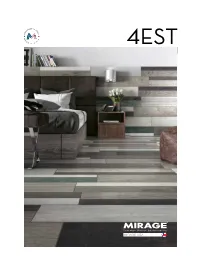

PORCELAIN TILE PORCELAIN TILE INDEX moodboard .02 color palette .03 colors & sizes . 1 8 sizes, finishes and packaging .22 field tile application areas .23 tile performance data .23 theconcept COLLECTION With its unique style, 4est offers an original take on wood: a mix of colors and graphic patterns that move away from the traditional canons of beauty, for a modern, eye-catching mash-up. A porcelain stoneware collection with excellent technical performance, where natural and recycled wood blend together into a mood with a raw yet supremely contemporary flavor, giving rise to intense patterns and colors. 4EST collection is designed in Italy and manufactured in USA Photographed samples are intended to give an approximate idea of the product. Colors and textures shown are not binding and may vary from actual products. Samples can be ordered from Mirage U.S.A. website: www.mirageusa.net/samples inspiredMOODBOARD by paletteCOLOR Available in both warm and cold shades, is embodied by the Curry and Indigo the combination of colors with wood nuances, offering a variety of style options. 2 | | 3 curry ET01 indigo ET02 Photographed samples are intended to give an approximate idea of the product. Colors and textures shown are not binding and may vary from actual products. 4 | curry | 5 FLOOR: curry ET01 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: scraped HM20 Brick 3”x12” NAT NOT RECT 6 | | 7 curry FLOOR: curry ET01 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: scraped HM20 Brick 3”x12” NAT NOT RECT 8 | | 9 indigo FLOOR: indigo ET02 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: maioliche light taupe HM -

When Creativity Strikes: News Shocks and Business Cycle Fluctuations

When Creativity Strikes: News Shocks and Business Cycle Fluctuations Silvia Miranda-Agrippino∗ Sinem Hacıo˘gluHoke† Bank of England Bank of England Centre for Macroeconomics (LSE) Data Analytics for Finance and Macro (KCL) Kristina Bluwstein‡ Bank of England August 22, 2018 Abstract We use monthly US utility patent applications to construct an external instrument for identification of technology news shocks in a rich-information VAR. Technology diffuses slowly, and affects total factor productivity in an S-shaped pattern. Responsible for about a tenth of economic fluctuations at business cycle frequencies, the shock elicits a slow, but large and positive response of quantities, and a sluggish contraction in prices, followed by an endogenous easing in the monetary stance. The ensuing economic expansion substantially anticipates any material increase in TFP. Technology news are strongly priced-in in the stock market on impact, but measures of consumers' expectations take sensibly longer to adjust, consistent with a New-Keynesian framework with nominal rigidities, and featuring informationally constrained agents. Keywords: Technology News Shocks; Business Cycle; Identification with External Instruments; Patents Applications. JEL Classification: E23, E32, O33, E22, O34 ∗Monetary Analysis, Bank of England, Threadneedle Street, London EC2R 8AH, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.silviamirandaagrippino.com †Financial Stability, Strategy and Risk. E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.sinemhaciogluhoke.com ‡Financial Stability, Strategy and Risk. E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.kristinabluwstein.com/ We are grateful to Franck Portier, Michael McMahon, Emanuel M¨onch, and seminar partici- pants at the Bank of England for useful comments and discussions. -

Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio

The Journal of the American Art Pottery Association, v.14, n. 2, p. 12-14, 1998. © American Art Pottery Association. http://www.aapa.info/Home/tabid/120/Default.aspx http://www.aapa.info/Journal/tabid/56/Default.aspx ISSN: 1098-8920 Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio By James L. Murphy For about five years during the late 1930s, the combination of inventive and artistic talent pro- vided by Walter D. Ford (1906-1988) and Paul V. Bogatay (1905-1972), gave life to Ford Ceramic Arts, Inc., a small and little-known Columbus, Ohio, firm specializing in ceramic art and design. The venture, at least in the beginning, was intimately associated with Ohio State University (OSU), from which Ford graduated in 1930 with a degree in Ceramic Engineering, and where Bogatay began his tenure as an instructor of design in 1934. In fact, the first plant, begun in 1936, was actually located on the OSU campus, at 319 West Tenth Avenue, now the site of Ohio State University’s School of Nursing. There two periodic kilns produced “decorated pottery and dinnerware, molded porcelain cameos, and advertising specialties.” Ford was president and ceramic engineer; Norman M. Sullivan, secretary, treasurer, and purchasing agent; Bogatay, art director. Subsequently, the company moved to 4591 North High Street, and Ford's brother, Byron E., became vice-president. Walter, or “Flivver” Ford, as he had been known since high school, was interested primarily in the engineering aspects of the venture, and it was several of his processes for producing photographic images in relief or intaglio on ceramics that distinguished the products of the company. -

6-12-03 Letter.Ppc

FRBSF ECONOMIC LETTER Number 2004-17, July 9, 2004 New Keynesian Models and Their Fit to the Data Central banks use macroeconomic models to help Hybrid New Keynesian models frame the issues that they face, to mold their ideas, Hybrid New Keynesian models have the canonical and to guide them in their decisionmaking.While model at their core, but they introduce a number a wide range of models are available, economists of important modifications.Typically these modi- are increasingly examining monetary policy issues fications seek to generate persistence in output and the design of optimal monetary policies in and inflation in order to slow down the rapid the context of “New Keynesian” macroeconomic adjustments that occur in the canonical model. models. New Keynesian models are notable for using microeconomic principles to describe the Consider, for a moment, the canonical model (see, behavior of households and firms, while allowing for example, Rotemberg and Woodford 1997). price and/or wage rigidities and inefficient market Households are assumed to smooth consumption outcomes. One particular model, often called the by saving or by borrowing against expected future canonical New Keynesian model, has received income; specifically, they save more when interest special attention, not only because it is easy to rates are high and consume more when interest work with, but also because it succinctly summa- rates are low. Firms are assumed to have some rizes the principal mechanisms through which market power, allowing those selling similar prod- policy interventions affect the economy. ucts to charge different prices. Although firms choose the price that they charge for their product, The canonical model does have some drawbacks, costs associated with changing prices—re-labeling however. -

Intellectual Property's Leviathan

KAPCZYNSKI_BOOKPROOF (DO NOT DELETE) 12/3/2014 2:10 PM INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY’S LEVIATHAN AMY KAPCZYNSKI* Neoliberalism is a complex, multifaceted concept. As such, it offers many possible points of entry into my primary field of study, that of intellectual property (IP) law. We might begin by investigating tensions between IP law and a purely economic conception of neoliberalism, for example.1 Or we might consider whether or how IP law might be “insulated from democratic governance” while also being rapidly assembled.2 In these few pages, I want to focus instead on a different line of inquiry, one that reveals the powerful grip that one particular neoliberal conception has on our contemporary imaginary: the neoliberal conception of the state. Today, both those who defend robust private IP law and their most prominent critics, I will show, typically describe Copyright © 2014 by Amy Kapczynski. This article is also available at http://lcp.law.duke.edu/. * Associate Professor of Law, Yale Law School. Many thanks to Talha Syed, David Grewal, and Jed Purdy for helpful conversation and comments. This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International license and should be reproduced as “first published in 77 LAW & CONTEMP. PROBS 131 (Fall 2014).” 1. Neoliberalism is commonly understood in economic terms. See, e.g., David Singh Grewal & Jedediah Purdy, Introduction: Law and Neoliberalism, 77 LAW & CONTEMP. PROBS., no. 4, 2014 at 1. David Harvey has argued, however, that neoliberalism as “a political project to re-establish the conditions for capital accumulation and to restore the power of economic elites” tends to prevail over the “economic utopian” conception of neoliberalism. -

Overcoming Intellectual Property Monopolies in the COVID-19 Pandemic

MSF Briefing Document July 2020 Overcoming intellectual property monopolies in the COVID-19 pandemic Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is responding to the global COVID-19 pandemic, providing treatment and care for people with COVID-19, protecting people living in vulnerable conditions, and ensuring uninterrupted essential health services for people suffering from other diseases.1 Having universal access to existing and future tools for treatment, diagnosis and prevention is critical. MSF has repeatedly witnessed how exclusive rights and monopolies granted to pharmaceutical corporations, resulting in high prices and blocking generic competition, have had a negative impact on our medical actions in different countries.2 For example, in the past, high prices for patented medicines have undermined the capacity of countries to provide access to treatment for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis C and cancer to all patients who need them. However, the impact of intellectual property (IP) monopolies is not limited to drugs. The availability of more affordable pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and human papillomavirus vaccine in low- and middle-income countries has been delayed due to unmerited patents on key technologies blocking follow-on producers.3 Intellectual property monopolies in the COVID-19 pandemic While several of the drugs being trialled as COVID-19 treatments are now off patent, patented drugs and experimental drugs are also being trialled, and some of which are under patent protection in many developing countries.4 With control over the market as a result of patents or other exclusive rights, pharmaceutical companies could determine how global production and supply chain are organised, who ultimately has access, who can produce medicines and where they can be supplied. -

64997 Frontier Loriann

[ FRESH TAKE ] Thrown for a Loop factory near his Staffordshire hometown, Stoke-on-Trent. Wedgwood married traditional craftsmanship with A RESILIENT POTTERY COMPANY FACES progressive business practices and contemporary design. TRYING TIMES He employed leading artists, including the sculptor John Flaxman, whose Shield of Achilles is in the Huntington by Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell collection, along with his Wedgwood vase depicting Ulysses at the table of Circe. As sturdy as they were beautiful, Wedgwood products made high-quality earthenware available to the middle classes. his past winter, Waterford Wedgwood found itself teetering on the edge of bankruptcy like a ceramic vase poised to topple from its shelf. As the company struggles A mainstay of bridal registries, the distinctive for survival, visitors to The Tearthenware is equally at home in museums around the world, including The Huntington. Now owned by an Irish firm, the once-venerable pottery manufactory was founded Huntington can appreciate by Englishman Josiah Wedgwood in 1759. As the company struggles for survival, visitors to The Huntington can appre - what a great loss its demise ciate what a great loss its demise would be. A look at the firm’s history reveals that the current crisis is just the most recent would be. of several that Wedgwood has overcome in its 250 years. The story of Wedgwood is one of the great personal and Today, Wedgwood is virtually synonymous with professional triumphs of the 18th century. Born in 1730 into Jasperware, an unglazed vitreous stoneware produced from a family of potters, Josiah Wedgwood started working at the barium sulphate. It is usually pale blue, with separately age of nine as a thrower, a craftsman who shaped pottery on molded white reliefs in the neoclassical style. -

No

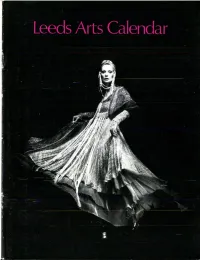

I LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED !>t;>rtin>»»ith thr f>rst issue publ>shed >n l947, thc cntin I ii ii) »fili Calindar is now availabl< on mi< ro- film. I'>'rit( I'(>r inl<)rmati<)n <>r scud ord('rs dirc( t t<): I 'nivrrsi< < .'>If< rolilms. Inc., 300:)I /r< h Ro»d, i><nn Arbor, Xfichit,an 4II f06, bhS.A. Leeds Art Collections Fund 'I'h>s >( i>i»tppri>l t(i all 'w'h(l;n'('nt('>'('sll'd it> th< A> ts. 'I'h< I.«ds Art Coll<« >ious Fund is tl>< s<)u>'(( <if''( t uhi> I'undo f()r huff«>» works of'rt Ii)r th< I.r<do (<)ilia ti(in. 0'< >(a>n< ni<ir< subscribing incmbcrs to Siv< / a or upwards ra< h >car. I't'hy not id('n>il'I yours( If with th('>'t (»><if('>') and I cn>f)l(. c'wsan»: '('c('>v('ol«' Ilti Cilli'lliliii''('(', >'<'('<'>>'('nv>tat«)i>s to I'un< Co< er: all ti<ins, privati > i< ws;in<I <irt»;>nis«I visits tu f)lt>('('s of'nt('n Dre)> by f3ill G'ibb, til7B Ilu «ater/i>It deroration im thi s>. In writin>» l<>r an appli( a>i<i>i fi>r»i Io (h(. die» ii hy dli ion Combe, lhe hat by Diane Logan for Bill Hr»n I ii'<i )i(im. l ..II..I inol<l E)»t.. Butt()le)'tii'i't. I i'eili IO 6'i bb, the shoe> by Chelsea Cobbler for Bill Gibb.