PREPARING a CONDUCTING RECITAL by NATHANIEL JOSEPH GOUGE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 AMTA Conference Promises to Bring You Many Opportunities to Network, Learn, Think, Play, and Re-Energize

Celebrating years Celebrating years ofof musicmusic therapytherapy the past... t of k ou oc R re utu e F th to in with ll nd o Music a R Therapy official conference program RENAISSANCE CLEVELAND HOTEL Program Sponsored by: CLEVELAND, OHIO welcome ...from the Conference Chair elcome and thank you for joining us in Cleveland to celebrate sixty years of music Wtherapy. And there is much to celebrate! Review the past with the historical posters, informative presentations and the inaugural Bitcon Lecture combining history, music and audience involvement. Enjoy the present by taking advantage of networking, making music with friends, new and old, and exploring some of the many exciting opportunities available just a short distance from the hotel. The conference offers an extensive array of opportunities for learning with institutes, continuing education, and concurrent sessions. Take advantage of the exceptional opportunities to prepare yourself for the future as you attend innovative sessions, and talk with colleagues at the clinical practice forum or the poster research session. After being energized and inspired the challenge is to leave Cleveland with both plans and dreams for what we can accomplish individually and together for music therapy as Amy Furman, MM, MT-BC; we roll into the next sixty years. AMTA Vice President and Conference Chair ...from the AMTA President n behalf of the AMTA Board of Directors, as well as local friends, family and colleagues, Oit is my distinct privilege and pleasure to welcome you to Cleveland to “rock out of the past and roll into the future with music therapy”! In my opinion, there is no better time or place to celebrate 60 years of the music therapy profession. -

A Stellar Lament of Lost Love

MASTERPIECE A Stellar Lament of Lost Love Hoagy Carmichael’s Star Dust, with lyrics by Mitchell Parish, is probably the most-recorded song in history. By John Edward Hasse Published originally in The Wall Street Journal, Aug. 23, 2019 Love is now the star dust of yesterday The music of the years gone by. What is probably the most-recorded American song in history began as melodic fragments imagined by a former Indiana University student named Hoagland “Hoagy” Carmichael. When he finished fiddling with his wordless tune, he had the beginnings of an American classic, StarDust that surpassed his later evergreens such as Skylark, Lazy River, and Georgia on My Mind and stood apart from all other popular songs. At the piano, he toyed with his ideas for months until the piece was first recorded by a group of his pals on Halloween in 1927. Carmichael was under the musical spell of the storied comet-in-the-sky cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, whose lyricism enraptured the young pianist. Like an elegant Beiderbecke improvisation captured in midair for all time, Star Dust has the fresh and spontaneous quality of a jazz solo. So striking is the melody line that it can be played naked—no harmonies—and stand as a remarkable statement. The allure of Star Dust begins with its title, suggesting a magical quality. The song is brilliant because of its originality, artistry and adaptability to many musical voices, both instrumental and vocal. It became a standard because so many musicians, from Louis Armstrong to Frank Sinatra, and their audiences too, embraced its charms. -

Just Hear Those Sleigh Bells Jingle-Ing, Ring-Ting Tingle-Ing, Too We're Riding

Sleigh Ride Just hear those sleigh bells jingle-ing, ring-ting tingle-ing, too Come on, it's lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you Outside the snow is falling and friends are calling "yoo hoo" (Echo - Yoo Hoo) Corne on, it's lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you Giddy-yap giddy-yap giddy-yap Iet's go Let's look at the snow We're riding in a wonderland of snow Giddy-yap giddy-yap giddy-yap it's grand Just holding your hand We're gliding along with the song Of a wintry fairy land Our cheeks are nice and rosy and comfy cozy are we We're snuggled up together like two birds of a feather would be Let's take that road before us and sing a chorus or two Come on it's lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you There's a birthday party at the home of Farmer Gray It'll be the perfect ending of a perfect day We'll be singing the songs we love to sing without a single stop At the fireplace while we watch the chestnuts pop Pop! Pop! Pop! There's a happy feeling nothing in the world can buy When they pass around the coffee and the pumpkin pie It'll nearly be like a picture print by Currier and Ives These wonderful things are the things We remember all through our lives These wonderful things are the things We remember all through our lives Just hear those sleigh bells jingle-ing, ring-ting tingle-ing, too Come on, it's iovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you Outside the snow is falling and friends are calling "yoo hoo" Come on, it's lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you Lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you----- (Say) - Sleigh Ride! Í $N@w DAY I cet up. -

Community Health Worker Newsletter 6

Cleveland's Own Community Health Workers Heart, Body & Soul Newsletter Caring for the Caregiver ~ Who's taking care of you? ~ The holiday season is a perfect time to reflect on your blessings and seek out ways to make life better for those around us.~ PSCHYCOLOGICAL SELF-CARE ~Original article from Harvard Medical School Health Blog The holiday season is full of excitement but can also be a time of stress. The stress of travel, the stress of long lines in stores and new for 2020, an ongoing health pandemic. For many, the holiday season also means taking care of others. However, this leaves little time for taking care of oneself. Remember, as the flight attendants say, you need to put on your own oxygen mask first before helping others. Below is a calendar full of ideas on how to practice self-care during this holiday season. So, enjoy the holidays and remember to take time to care for your own needs and keep the ME in MERRY! EMOTIONAL SELF-CARE ~ submitted by P5 Ventures Team Members One way to lift your spirits during the holiday season is through song. Here's a list of some of our favorite holiday season songs. Make a cup of hot cocoa (perfect with this month's recipe) and let the music melt the stress away! Walking in A Winter Wonderland - Dean Martin It's the Most Wonderful Time - Andy Williams Santa Baby - Ertha Kitt The Little Drummer Boy - Bing Crosby Rocking Around the Christmas Tree - Brenda Lee It's Beginning to Look A Lot Like Christmas - Johnny Mathis White Christmas - Bing Crosby Sleigh Ride - The Ronettes The Christmas Song - Nat King Cole All I Want for Christmas is You - Mariah Carey Santa Claus is Coming to Town - The Jackson Five Someday at Christmas - Stevie Wonder Do They Know It's Christmas - Band Aid My Favorite Things - Julie Andrews December is: AIDS Awareness Month World AIDS Day is Dec. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F. Henri Klickmann Harold Rossiter Music Co. 1913 Sack Waltz, The John A. Metcalf Starmer Eclipse Pub. Co. [1924] Sadie O'Brady Billy Lindemann Billy Lindemann Broadway Music Corp. 1924 Sadie, The Princess of Tenement Row Frederick V. Bowers Chas. Horwitz J.B. Eddy Jos. W. Stern & Co. 1903 Sail Along, Silv'ry Moon Percy Wenrich Harry Tobias Joy Music Inc 1942 Sail on to Ceylon Herman Paley Edward Madden Starmer Jerome R. Remick & Co. 1916 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailing Down the Chesapeake Bay George Botsford Jean C. Havez Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1913 Sailing Home Walter G. Samuels Walter G. Samuels IM Merman Words and Music Inc. 1937 Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy NA Tivick Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1914 Includes ukulele arrangement Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy Barbelle Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1942 Sakes Alive (March and Two-Step) Stephen Howard G.L. Lansing M. Witmark & Sons 1903 Banjo solo Sally in our Alley Henry Carey Henry Carey Starmer Armstronf Music Publishing Co. 1902 Sally Lou Hugo Frey Hugo Frey Robbins-Engel Inc. 1924 De Sylva Brown and Henderson Sally of My Dreams William Kernell William Kernell Joseph M. Weiss Inc. 1928 Sally Won't You Come Back? Dave Stamper Gene Buck Harms Inc. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 67, 1947-1948, Subscription

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 6-1492 SIXTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1947-1948 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1948, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot . President Henry B. Sawyer . Vice-President Richard C. Paine . Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. De Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Lewis Perry N. Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wilkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott George E. Judd, Manager 1281 [ ] © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © Only © © © © © © you can © © © © © © decide © © © © © © © © © © © Whether your property is large or small, it rep- © © resents the security for your family's future. Its ulti- © © © © mate disposition is a matter of vital concern to those © © you love. © © © © To assist you in considering that future, the Shaw- © © mut Bank has a booklet: "Should I Make a Will?" © © It outlines facts that everyone with property should © © © © know, and explains the many services provided by © © this Bank as Executor and Trustee. © © © © Call at any of our 2 J convenient 'offices, write or telephone © © for our booklet: "Should I Make a Will?" © © © © © © © © © The V^tional © © © © © Shawmut Bank © © 40 Water Street^ Boston © © Member Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation © © Capital $10,000,000 Surplus $20,000,000 © "Outstanding Strength"for 112 Years © © [ 1282 ] ! SYMPHONIANA Can you score 1 The "Missa Solemnis" 00? Peabody Award for Broadcasts Honor to Chaliapin New England Opera Theatre Finale FASHION THE 'MISSA SOLEMNIS" QUIZ Instead of trying to describe the mighty Mass in D major, to be per- 1. -

Dear Parents, Mrs. Novak

Winter Concert 2015 Dear Parents, The Winter Concert is coming up fast! Please take some time to listen to your child sing these songs. Have your child go through line by line and work on words they may have forgotten. The students are eager to show you all of their hard work! Thank you! Mrs. Novak - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - K-1-2 All Sing We Wish You A Merry Christmas We wish you a Merry Christmas. We wish you a Merry Christmas. We wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Good tidings to you, wherever you are. Good tidings for Christmas and a Happy New Year. Oh, bring us some figgy pudding. Oh, bring us some figgy pudding. Oh, bring us some figgy pudding, now bring some right here. Good tidings to you, wherever you are. Good tidings for Christmas and a Happy New Year. We won’t go until we get some. We won’t go until we get some. We won’t go until we get some, so bring some right here. Good tidings to you, wherever you are. Good tidings for Christmas and a Happy New Year. We wish you a Merry Christmas. We wish you a Merry Christmas. We wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Merry Christmas! Kindergarten Songs Jingle Bells Dashing through the snow In a one horse open sleigh, O’er the fields we go, Laughing all the way. Bells on bobtail ring, Making spirits bright; What fun it is to ride and sing A sleighing song tonight. Oh! Jingle bells, jingle bells, Jingle all the way; Oh what fun it is to ride In a one horse open sleigh. -

Application for National Elk Refuge Interpretive Horse-Drawn Sleigh / Wagon Ride Contract

Application For National Elk Refuge Interpretive Horse-Drawn Sleigh / Wagon Ride Contract To: Grand Teton Association (GTA) through a Partnership Agreement with National Elk Refuge PO Box 510 Jackson, WY 83001 In accordance with the prospectus dated May 16, 2017, for the contract opportunity of providing winter horse-drawn sleigh/wagon rides on the National Elk Refuge (Refuge), I (____) we (____) hereby agree with the requirements specified in the Prospectus and submit the following offer: 1. Operation Provide horse-drawn sleigh/wagon rides onto the National Elk Refuge during the winter season for the public. The sleigh ride operation will be open daily from mid-December through early April, except for Christmas Day, with the start date determined by the National Elk Refuge. When snow cover on the ground is too sparse to allow sleighs to move easily, wagons will be substituted. Visitors will be transported from the ticket sales location in the Jackson Hole & Greater Yellowstone Visitor Center (the Visitor Center) at 532 N. Cache Street, Jackson, Wyoming, through a gate, and onto the Refuge to the sleigh boarding area. Visitors will be returned to the Visitor Center after completing their tour. Shuttle buses will run at appropriate intervals to keep sleighs full and minimize the wait for visitors both in boarding the sleigh and in returning to the Visitor Center. All operations will be conducted pursuant to the terms and provisions of the Prospectus and the Submission of Proposals. Agree to provide ____Yes ____No 2. Term The length of the proposed contract is five (5) years, with a renewal period of five (5) additional years depending upon performance of the company/individual awarded the solicitation. -

4965450-C80a2a-714861017120.Pdf

The idea of doing a Christmas album has been floating around the Vocal Point camp for several years. Those who have attended a VP concert know that we love Christmas music and will often sing it regardless of the time of year. But never have we been able to devote an entire show or recording to this special holiday— until now! He Is Born is a collection of traditional holiday favorites plus some new carols wrapped in that rich, distinctive VP a cappella bow. This long-awaited album has been crafted to aid in commemorating the most nostalgic and meaningful aspects of the Christmas season. To help us celebrate, we’ve invited some special guests—including BYU Noteworthy, nationally acclaimed One Voice Children’s Choir, and powerhouse vocalists Ryan Innes (Vocal Point alumnus) and Elisha Garrett—to join their voices with ours to make this a wonderful Christmas celebration. Christmas is my favorite time of year—a time of rejoicing, of solemn thanksgiving, of gift giving, of pleasures both modern and traditional, and of being together with family and friends. In that spirit we are excited to share a little of our family Christmas celebration with you. My sincere hope is that He Is Born will become part of your Christmas for years to come. —McKay Crockett, He Is Born producer, BYU Vocal Point director and alumnus 1 GOD REST YE MERRY, GENTLEMEN Traditional English carol; arr. McKay Crockett 2 HE IS BORN Aaron Edson; arr. BYU Vocal Point Featuring Ryan Innes 3 SILENT NIGHT Joseph Mohr, Franz Xaver Gruber; arr. -

100% Print Rights Administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH

100% Print Rights administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN *A BRIDGE TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS A CHANGE IS GONNA COME (from “ Malcolm X”) Words and Music by SAM COOKE A CHI (HURT) (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by JIMMIE CRANE and AL JACOBS A CHICKEN AIN’T NOTHING BUT A BIRD Words and Music by EMMETT ‘BABE’ WALLACE A DARK KNIGHT (from “ The Dark Knight ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER and JAMES HOWARD A HARD TEACHER (from “ The Last Samurai ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER A JOURNEY IN THE DARK (from “ The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring”) Music by HOWARD SHORE Lyrics by PHILIPPA BOYENS A MOTHER’S PRAYER (from “ Quest for Camelot ”) Words and Music by CAROLE BAYER SAGER and DAVID FOSTER *A WINDOW TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS ACCORDION JOE Music by CORNELL SMELSER Lyrics by PETER DALE WIMBROW ACES HIGH MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN AIN'T GOT NO (Excluding Europe) Music by GALT MACDERMOT Lyrics by JAMES RADO and GEROME RAGNI AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (from “ Ain’t Misbehavin’ ) (100% in Scandinavia, including Finland) Music by THOMAS “FATS” WALLER and HARRY BROOKS Lyrics by ANDY RAZAF ALL I DO IS DREAM OF YOU (from “ Singin’ in the Rain ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by NACIO HERB BROWN Lyrics by ARTHUR FREED ALL TIME HIGH (from “ Octopussy ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by JOHN BARRY Lyrics by TIM RICE ALMIGHTY GOD (from “ Sacred Concert No. -

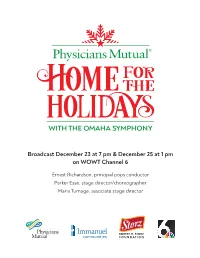

Broadcast December 23 at 7 Pm & December 25 at 1 Pm on WOWT Channel 6

Broadcast December 23 at 7 pm & December 25 at 1 pm on WOWT Channel 6 Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor Parker Esse, stage director/choreographer Maria Turnage, associate stage director ROBERT H. STORZ FOUNDATION PROGRAM The Most Wonderful Time of the Year/ Jingle Bells JAMES LORD PIERPONT/ARR. ELLIOTT Christmas Waltz VARIOUS/ARR. KESSLER Happy Holiday - The Holiday Season IRVING BERLIN/ARR. WHITFIELD Joy to the World TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Mother Ginger (La mère Gigogne et Danse russe Trepak from Suite No. 1, les polichinelles) from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY We Are the Very Model of a God Bless Us Everyone from Modern Christmas Shopping Pair A Christmas Carol from Pirates of Penzance ALAN SILVESTRI/ARR. ROSS ARTHUR SULLIVAN/LYRICS BY RICHARDSON Silent Night My Favorite Things from FRANZ GRUBER/ARR. RICHARDSON The Sound of Music RICHARD RODGERS/ARR. WHITFIELD Snow/Jingle Bells IRVING BERLIN/ARR. BARKER O Holy Night ADOLPH-CHARLES ADAM/ARR. RICHARDSON Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow JULE STYNE/ARR. SEBESKY We Need a Little Christmas JERRY HERMAN/ARR. WENDEL Frosty the Snowman WALTER ROLLINS/ARR. KATSAROS Hark All Ye Shepherds TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Sleigh Ride LEROY ANDERSON 2 ARTISTIC DIRECTION Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor and resident conductor of the Omaha Symphony, is the artistic leader of the orchestra’s annual Christmas Celebration production and internationally performed “Only in Omaha” productions, and he leads the successful Symphony Pops, Symphony Rocks, and Movies Series. Since 1993, he has led in the development of the Omaha Symphony’s innovative education and community engagement programs. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 72

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY SEVENTY-SECOND SEASON I 95 2 " I 953 Tuesday Evening Series BAYARD TUCKERMAN, J«. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON ROBERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON. Ja. HERBERT SEARS TUCKERMAN OBRION, RUSSELL & CO Insurance of Every Description "A Good Reputation Does Not Just Happen — It Must Be Earned.*' 108 Water Street Los Angeles, California Boston, Mass. 3275 Wilshire Blvd. Telephone Lafayette 3-S700 Dunkirk 8-3S16 SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 6-1492 SEVENTY^SECOND SEASON, 1952-1953 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burr The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Jacob J. Kaplan Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. De Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Michael T. Kelleher Theodore P. Ferris Lewis Perry Alvan T. Fuller Edward A. Taft N. Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wilkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott George E. Judd, Manager T. D. Perry, Jr. N. S. Shirk, Assistant Managers [«] 4* 4» * * * * * 4 UNTROUBLED 4* * + * * * * * PASSAGE * * The Living Trust 4* * * * It is an odd contradiction that financial success sometimes brings * less, rather than more, personal freedom to enjoy it. Instead of un- 4* 4* troubled passage, there is often the difficult job of steering invest- 4* * ments through more and more complex channels. * 4» For this reason, a steadily increasing number of substantial men * and women are turning to the Living Trust. * 4* 4* The man or woman who has acquired capital which he or she wishes to invest for income, yet lacks either the necessary time or * 4* knowledge .