What Should We Know About the Next Recession? | Economic Policy Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* * Top Incomes During Wars, Communism and Capitalism: Poland 1892-2015

WID.world*WORKING*PAPER*SERIES*N°*2017/22* * * Top Incomes during Wars, Communism and Capitalism: Poland 1892-2015 Pawel Bukowski and Filip Novokmet November 2017 ! ! ! Top Incomes during Wars, Communism and Capitalism: Poland 1892-2015 Pawel Bukowski Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics Filip Novokmet Paris School of Economics Abstract. This study presents the history of top incomes in Poland. We document a U- shaped evolution of top income shares from the end of the 19th century until today. The initial high level, during the period of Partitions, was due to the strong concentration of capital income at the top of the distribution. The long-run downward trend in top in- comes was primarily induced by shocks to capital income, from destructions of world wars to changed political and ideological environment. The Great Depression, however, led to a rise in top shares as the richest were less adversely affected than the majority of population consisting of smallholding farmers. The introduction of communism ab- ruptly reduced inequalities by eliminating private capital income and compressing earn- ings. Top incomes stagnated at low levels during the whole communist period. Yet, after the fall of communism, the Polish top incomes experienced a substantial and steady rise and today are at the level of more unequal European countries. While the initial up- ward adjustment during the transition in the 1990s was induced both by the rise of top labour and capital incomes, the strong rise of top income shares in 2000s was driven solely by the increase in top capital incomes, which make the dominant income source at the top. -

Macroeconomic and Financial Risks: a Tale of Mean and Volatility

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System International Finance Discussion Papers Number 1326 August 2021 Macroeconomic and Financial Risks: A Tale of Mean and Volatility Dario Caldara, Chiara Scotti and Molin Zhong Please cite this paper as: Caldara, Dario, Chiara Scotti and Molin Zhong (2021). \Macroeconomic and Fi- nancial Risks: A Tale of Mean and Volatility," International Finance Discussion Papers 1326. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2021.1326. NOTE: International Finance Discussion Papers (IFDPs) are preliminary materials circulated to stimu- late discussion and critical comment. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the research staff or the Board of Governors. References in publications to the International Finance Discussion Papers Series (other than acknowledgement) should be cleared with the author(s) to protect the tentative character of these papers. Recent IFDPs are available on the Web at www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/. This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network electronic library at www.ssrn.com. Macroeconomic and Financial Risks: A Tale of Mean and Volatility∗ Dario Caldara† Chiara Scotti‡ Molin Zhong§ August 18, 2021 Abstract We study the joint conditional distribution of GDP growth and corporate credit spreads using a stochastic volatility VAR. Our estimates display significant cyclical co-movement in uncertainty (the volatility implied by the conditional distributions), and risk (the probability of tail events) between the two variables. We also find that the interaction between two shocks|a main business cycle shock as in Angeletos et al. -

Senate Banking Committee Hearing: Federal Reserve Nominees 5.15.2018

Senate Banking Committee Hearing: Federal Reserve Nominees 5.15.2018 On May 15th, the Senate Banking Committee held a hearing to consider the following nominations: The Honorable Richard Clarida, of Connecticut, to be a Member and Vice Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Ms. Michelle Bowman, of Kansas, to be a Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Key Takeaways Both nominees expressed support for the tailoring of financial regulation to the size and complexity of the institution, but highlighted the need to continue to ensure safety and soundness in the financial system. Both nominees expressed support for the continued normalization of the Fed’s balance sheet. Democratic Members asked nominees about recent Federal Reserve proposals that would adjust capital standards. The following themes consistently emerged throughout the hearing: Tailoring of regulations o Chairman Crapo (R-ID) asked the nominees their thoughts on tailoring regulations to the size and complexity of individual institutions. Clarida said that tailoring and efficiency of regulations are important goals while at the same time continuing to ensure the safety and soundness of the financial system. Bowman highlighted the need to apply the appropriate amount of regulation depending on size and complexity of the institution. o Senator Tillis (R-NC) asked witnesses about whether S.2155 was an appropriate way to tailor regulations. Bowman discussed the importance of tailoring regulations but did not specifically discuss 2155. Fed balance sheet / Quantitative Easing o Chairman Crapo (R-ID) asked the nominees about normalization of the Fed balance sheet. Clarida said that Fed Chairman Powell’s recent proposal seems to make sense, but he has not studied the numbers in detail yet. -

The Shape of the Coming Recovery

The Shape of the Coming Recovery Mark Zandi July 9, 2009 he Great Recession continues. Given these prospects, a heated debate will resume spending more aggressively. After 18 months of economic has broken out over the strength of the Businesses may also have slashed too T contraction, 6.5 million jobs have coming recovery, with the back-and-forth deeply and, once confidence is restored, been lost, and the unemployment rate is simplifying into which letter of the alphabet will ramp up investment and hiring. fast approaching double digits. Many with best describes its shape. Pessimists dismiss this possibility, jobs are seeing their hours cut—the length Optimists argue for a V-shaped arguing instead for a W-shaped or double- of the average workweek fell to a record recovery, with a vigorous economic dip business cycle, with the economy low in June—and are taking cuts in pay as revival beginning soon. History is on their sliding back into recession after a brief overall wage growth stalls. Balance sheets side. The one and only regularity of past recovery, or an L-shaped cycle in which have also been hit hard: Some $15 trillion business cycles is that severe downturns the recession is followed by measurably in household wealth has evaporated, the have been followed by strong recoveries, weaker growth for an extended period. federal government has run up deficits and shallow downturns by shallow A W-shaped cycle seems more likely approaching $1.5 trillion, and many state recoveries.2 The 2001 recession was the if policymakers misstep. The last time and local governments have borrowed mildest since World War II—real GDP the economy suffered a double-dip was heavily to fill gaping budget holes. -

Supporting Documents for DSGE Models Update

Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 02/09/2018 BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Division of Monetary Affairs FOMC SECRETARIAT Date: June 11, 2012 To: Research Directors From: Deborah J. Danker Subject: Supporting Documents for DSGE Models Update The attached documents support the update on the projections of the DSGE models. 1 of 1 Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 02/09/2018 System DSGE Project: Research Directors Drafts June 8, 2012 1 of 105 Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 02/09/2018 Projections from EDO: Current Outlook June FOMC Meeting Hess Chung, Michael T. Kiley, and Jean-Philippe Laforte∗ June 8, 2012 1 The Outlook for 2012 to 2015 The EDO model projects economic growth modestly below trend through 2013 while the policy rate is pegged to its e ective lower bound until late 2014. Growth picks up noticeably in 2014 and 2015 to around 3.25 percent on average, but infation remains below target at 1.7 percent. In the current forecast, unemployment declines slowly from 8.25 percent in the third quarter of 2012 to around 7.75 percent at the end of 2014 and 7.25 percent by the end of 2015. The slow decline in unemployment refects both the inertial behavior of unemployment following shocks to risk-premia and the elevated level of the aggregate risk premium over the forecast. By the end of the forecast horizon, however, around 1 percentage point of unemployment is attributable to shifts in household labor supply. -

NY Fed President ❖ Lael Brainard – Governor ❖ Randall Quarles – Vice Chair for Supervision ❖ Michelle Bowman-Governor

1 2 Interest Rates – from 3000 BC Source: Business Insider 3 Yield Curve 101 ❖ Fed Funds – 2.40% (2.25%-2.50%) ❖ +75 bps ❖ =3.15% 2-year note yield (2.52%) ❖ +100 bps ❖ =4.15% 10-year note yield (2.66%) ❖ +50 bps ❖ =4.40% 30-year bond yield (3.00%) ❖ Yield Curve is Flat 4 Treasury Yield Curve-2018-2019 Source: Bloomberg 5 Treasury Yield Curve 2018-2019 Source: Bloomberg 6 U.S. vs. German Yield Curves Source: Bloomberg 7 Source: Walt Handelsman - Newsday 8 Economic Growth – 2004-2018 Source: BEA & Bloomberg 9 Economic Growth – 1947-2018 Source: BEA & Bloomberg 10 11 Key to Economy – Innovative New Jobs 12 Beneficiaries of Economic Innovation 13 Measures of Unemployment Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics •U-3: Total unemployed, as a percent of the civilian labor force (this is the definition used for the official unemployment rate). •U-6: Total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers. 14 U.S. Unemployment Rate U-3 Source: BLS and Bloomberg 15 U.S. Unemployment Rate U-6 Source: BLS and Bloomberg 16 U.S. Non-farm Payrolls (2009-Present) Source: BLS and Bloomberg 17 U.S. Non-farm Payrolls (1939-Present) Source: BLS and Bloomberg 18 Weekly Initial Jobless Claims(2009-Present) Source: DOL and Bloomberg 19 Weekly Initial Jobless Claims(1967-Present) Source: DOL and Bloomberg 20 21 German Inflation – 1918-1923 Source: BEA & Bloomberg 22 Wages vs Inflation (PCE Core YoY) – 2007-2019 Source: BEA, BLS & Bloomberg -

US Dec FOMC Minutes: on Pause for “A Time”

Global Economics & Markets Research Email: [email protected] URL: www.uob.com.sg/research Macro Note US Dec FOMC Minutes: On Pause For “A Time” Monday, 06 January 2020 . In the latest minutes, markets did not get much new insights on what would change the outlook for the Fed Reserve policy rate trajectory. FOMC policy makers regarded current rate stance as likely to remain appropriate for ”a time”, helping to reinforce expectations for a Fed policy cycle pause after three sequential 25bps rate cuts in July, September and October but provided little else in Alvin Liew Senior Economist terms of new information. [email protected] . Similar to market expectations, we too subscribe to the view that the Fed Reserve will stay on Heng Koon How pause in its upcoming 28/29 January 2020 FOMC. But in contrast to the view of a more prolonged Head of Markets Strategy [email protected] Fed pause, we still expect the Fed to implement the next 25bps rate cut in 1Q 2020 which will be at the March FOMC, and thereafter to stay on pause again for the rest of 2020. The factors determining our Fed policy outlook is still the international trade developments and now, the additional factor of US-Iran developments. Conversely, if the trade negotiation progresses smoothly into 2020 and the US-Iran tensions does not boil over into a full-fledged military confrontation, then the “insurance” cut will be unnecessary. The view remains for the Fed Reserve to keep policy rates low or even lower in 2020. 10/11 Dec 2019 FOMC Minutes: Keeping Policy Steady For “A Time” The trouble brewing in the Middle East largely overshadowed the special Friday release of the 10/11 December 2019 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) minutes (4 Jan, Saturday 3am SGT) and markets did not get much new insights on what would change the outlook for the Fed from details of the minutes. -

FPI Pulling Apart Nov 15 Final

Pulling Apart: The Continuing Impact of Income Polarization in New York State Embargoed for 12:01 AM Thursday, Nov. 15, 2012 A Fiscal Policy Institute Report www.fiscalpolicy.org November 15, 2012 Pulling Apart: The Continuing Impact of Polarization in New York State Acknowledgements The primary author of this report is Dr. James Parrott, the Fiscal Policy Institute’s Deputy Director and Chief Economist. Frank Mauro, David Dyssegaard Kallick, Carolyn Boldiston, Dr. Brent Kramer, and Dr. Hee-Young Shin assisted Dr. Parrott in the analysis of the data presented in the report and in the editing of the final report. Special thanks are due to Elizabeth C. McNichol of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Dr. Douglas Hall of the Economic Policy Institute for sharing with us the data from the state- by-state analysis of income trends that they completed for the new national Pulling Apart report being published by their two organizations. This report would not have been possible without the support of the Ford and Charles Stewart Mott Foundations and the many labor, religious, human services, community and other organizations that support and disseminate the Fiscal Policy Institute’s analytical work. For more information on the Fiscal Policy Institute and its work, please visit our web site at www.fiscalpolicy.org. Embargoed for 12:01 AM Thursday, Nov. 15, 2012 FPI November 15, 2012 1 Pulling Apart: The Continuing Impact of Polarization in New York State Highlights In the three decades following World War II, broadly shared prosperity drew millions up from low-wage work into the middle class and lifted living standards for the vast majority of Americans. -

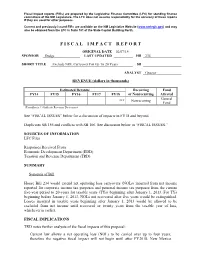

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current and previously issued FIRs are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov) and may also be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/14 SPONSOR Dodge LAST UPDATED HB 234 SHORT TITLE Exclude NOL Carryover For Up To 20 Years SB ANALYST Graeser REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Estimated Revenue Recurring Fund FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 or Nonrecurring Affected General *** Nonrecurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decreases) See “FISCAL ISSUES” below for a discussion of impacts in FY18 and beyond. Duplicates SB 156 and conflicts with SB 106. See discussion below in “FISCAL ISSUES.” SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Economic Development Department (EDD) Taxation and Revenue Department (TRD) SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 234 would extend net operating loss carryovers (NOLs) incurred from net income reported for corporate income tax purposes and personal income tax purposes from the current five-year period to 20-years for taxable years (TYs) beginning after January 1, 2013. For TYs beginning before January 1, 2013, NOLs not recovered after five years would be extinguished. Losses incurred in taxable years beginning after January 1, 2013 would be allowed to be excluded from net income until recovered or twenty years from the taxable year of loss, whichever is earlier. -

Federal Reserve Appointments and the Politics of Senate Confirmation

Federal Reserve appointments and the politics of Senate confirmation Caitlin Ainsley University of Washington [email protected] Abstract This paper examines the politicization of Federal Reserve (Fed) appointments. In contrast to the extant appointment literature's almost exclusive focus on ideological proximity as a predictor of Fed nominations and confirmations, I theorize that senators will be more likely to vote against confirmation when their constituents have little con- fidence in the Fed because it allows them to more credibly defer blame on the Fed for economic downturns. Drawing on novel estimates of state-level confidence in the Fed as well as new common space estimates of senators' and central bankers' monetary policy preferences, I demonstrate that when constituents do not have confidence in the Fed, senators are less likely to vote in favor of confirmation regardless of their ideological proximity to the nominee. The results have important implications for the ability to fill Fed vacancies and, in turn, the balance of power between the Fed and regional bank Presidents in the monetary policymaking process. Keywords: Federal Reserve, Senate Confirmation, Public Opinion, Central Bank Preferences JEL Codes: P16, E58, D72 1 Introduction This article investigates the politics of Senate confirmations for Federal Reserve (Fed) nomi- nations. Scholars of central banking have long recognized the importance of the appointment process for the politics of monetary policymaking. For many scholars, that is considered a primary channel through which partisan politics affects decision-making at the central bank (Adolph, 2013; Chappell, Havrilesky and McGregor, 1993; Chappell, McGregor and Ver- milyea, 2004). Given that conventional wisdom, it is unsurprising that presidential power to nominate individuals to the Fed's Board of Governors and its associated leadership po- sitions has received considerable attention in the extant literature. -

Essays on Time Inconsistent Policy

Essays on Time Inconsistent Policy By ©2016 Sijun Yu DPhil, University of Kansas, 2016 M.A., University of Kansas, 2013 B.Sc., University of Kansas, 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Department of Economics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________ Chair: William Barnett ____________________ Professor Zongwu Cai __________________ Professor John Keating _________________ Professor Jianbo Zhang _________________ Professor Paul Johnson Date Defended: 19 September 2016 The dissertation committee for Sijun Yu certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Essays on Time Inconsistent Policy ______________ Chair: William Barnett Date Approved: 19 September 2016 ii Essays on Time Inconsistent Policy Sijun Yu Abstract This research is mainly focused on the time-inconsistency during policy making process. It contains three chapters as follows: Chapter One is to research into the time-inconsistency problem in policy making with extensive form games. The paper divides the game into four scenarios: one-stage independent game, one-stage forecasting game, finite stage forecasting game and infinite period game. The first two games show that neither government nor public want to be type 1 and government always has an incentive to deviate from announced policy. The last two games are mainly focused on the possibilities that both players want to randomize their strategies. The games are able to conclude -

Supporting Documents for DSGE Models Update

Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 02/09/2018 BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Division of Monetary Affairs FOMC SECRETARIAT Date: December 3, 2012 To: Research Directors From: Deborah J. Danker Subject: Supporting Documents for DSGE Models Update The attached documents support the update on the projections of the DSGE models. 1 of 1 Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 02/09/2018 The Current Outlook and Alternative Policy Rule Simulations in EDO: December FOMC Meeting (Internal FR) Hess Chung November 27, 2012 1 Introduction This note describes the EDO forecast for 2012 to 2015, as well as a number of alternative monetary policy simulations in EDO, most undertaken as part of a special topic for the December Federal Reserve System DSGE project. Specifcally, given the EDO baseline forecast, we consider several alternative dates for the departure of the federal funds rate from the zero lower bound. Taking as given the initial conditions underlying the EDO forecast, we then simulate the results of switching to three alternative rules: a representative Taylor-type rule and two level-targeting rules (nominal income and price level targeting). Finally, we repeat these exercises taking the October Tealbook projection as the baseline. To summarize our qualitative results from these alternative rules simulations, we fnd that 1. Extensions of the period at the zero lower bound to periods where there is a considerable gap between the baseline and the e ective lower bound can have strongly stimulative e ects on both real activity, including unemployment, and infation, even in the very short term.