Family Adjustments to Large Scale Financial Crises US and Malaysian Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* * Top Incomes During Wars, Communism and Capitalism: Poland 1892-2015

WID.world*WORKING*PAPER*SERIES*N°*2017/22* * * Top Incomes during Wars, Communism and Capitalism: Poland 1892-2015 Pawel Bukowski and Filip Novokmet November 2017 ! ! ! Top Incomes during Wars, Communism and Capitalism: Poland 1892-2015 Pawel Bukowski Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics Filip Novokmet Paris School of Economics Abstract. This study presents the history of top incomes in Poland. We document a U- shaped evolution of top income shares from the end of the 19th century until today. The initial high level, during the period of Partitions, was due to the strong concentration of capital income at the top of the distribution. The long-run downward trend in top in- comes was primarily induced by shocks to capital income, from destructions of world wars to changed political and ideological environment. The Great Depression, however, led to a rise in top shares as the richest were less adversely affected than the majority of population consisting of smallholding farmers. The introduction of communism ab- ruptly reduced inequalities by eliminating private capital income and compressing earn- ings. Top incomes stagnated at low levels during the whole communist period. Yet, after the fall of communism, the Polish top incomes experienced a substantial and steady rise and today are at the level of more unequal European countries. While the initial up- ward adjustment during the transition in the 1990s was induced both by the rise of top labour and capital incomes, the strong rise of top income shares in 2000s was driven solely by the increase in top capital incomes, which make the dominant income source at the top. -

Zbwleibniz-Informationszentrum

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ahmadi, Maryam; Manera, Matteo Working Paper Oil Price Shocks and Economic Growth in Oil- Exporting Countries Working Paper, No. 013.2021 Provided in Cooperation with: Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM) Suggested Citation: Ahmadi, Maryam; Manera, Matteo (2021) : Oil Price Shocks and Economic Growth in Oil-Exporting Countries, Working Paper, No. 013.2021, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM), Milano This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/237738 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten -

A Three-Way Analysis of the Relationship Between the USD Value and the Prices of Oil and Gold: a Wavelet Analysis

AIMS Energy, 6(3): 487–504. DOI: 10.3934/energy.2018.3.487 Received: 18 April 2018 Accepted: 30 May 2018 Published: 08 June 2018 http://www.aimspress.com/journal/energy Research article A three-way analysis of the relationship between the USD value and the prices of oil and gold: A wavelet analysis Basheer H. M. Altarturi1, Ahmad Alrazni Alshammari1, Buerhan Saiti2,*, and Turan Erol2 1 Institute of Islamic Banking and Finance, International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2 Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University, Istanbul, Turkey * Correspondence: Email: [email protected]. Abstract: This study examines the relationships among oil prices, gold prices, and the USD real exchange rate. It adopts the wavelet approach as a nonlinear causality technique to decompose the data into various scales over time. Higher-order coherence and partial coherence were used to identify the lead-lag effect and mutual coherence function among the variables. The results show that changes in the USD exchange rate influence the prices of oil and gold negatively in the short- and medium-term. While in the long-term, the oil price has a negative impact on the value of the USD. Oil and gold are significantly linked and correlated because their prices are determined in USD. The findings of this paper have significant implications, particularly for risk management. Keywords: wavelet; partial wavelet coherence; U.S. dollar value; oil prices; gold prices 1. Introduction Examining the nexus between oil and gold is an established practice among researchers in the field of economics due to the importance of these variables. Oil is considered the primary driver of the economy. -

Macroeconomic and Financial Risks: a Tale of Mean and Volatility

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System International Finance Discussion Papers Number 1326 August 2021 Macroeconomic and Financial Risks: A Tale of Mean and Volatility Dario Caldara, Chiara Scotti and Molin Zhong Please cite this paper as: Caldara, Dario, Chiara Scotti and Molin Zhong (2021). \Macroeconomic and Fi- nancial Risks: A Tale of Mean and Volatility," International Finance Discussion Papers 1326. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2021.1326. NOTE: International Finance Discussion Papers (IFDPs) are preliminary materials circulated to stimu- late discussion and critical comment. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the research staff or the Board of Governors. References in publications to the International Finance Discussion Papers Series (other than acknowledgement) should be cleared with the author(s) to protect the tentative character of these papers. Recent IFDPs are available on the Web at www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/. This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network electronic library at www.ssrn.com. Macroeconomic and Financial Risks: A Tale of Mean and Volatility∗ Dario Caldara† Chiara Scotti‡ Molin Zhong§ August 18, 2021 Abstract We study the joint conditional distribution of GDP growth and corporate credit spreads using a stochastic volatility VAR. Our estimates display significant cyclical co-movement in uncertainty (the volatility implied by the conditional distributions), and risk (the probability of tail events) between the two variables. We also find that the interaction between two shocks|a main business cycle shock as in Angeletos et al. -

The Shape of the Coming Recovery

The Shape of the Coming Recovery Mark Zandi July 9, 2009 he Great Recession continues. Given these prospects, a heated debate will resume spending more aggressively. After 18 months of economic has broken out over the strength of the Businesses may also have slashed too T contraction, 6.5 million jobs have coming recovery, with the back-and-forth deeply and, once confidence is restored, been lost, and the unemployment rate is simplifying into which letter of the alphabet will ramp up investment and hiring. fast approaching double digits. Many with best describes its shape. Pessimists dismiss this possibility, jobs are seeing their hours cut—the length Optimists argue for a V-shaped arguing instead for a W-shaped or double- of the average workweek fell to a record recovery, with a vigorous economic dip business cycle, with the economy low in June—and are taking cuts in pay as revival beginning soon. History is on their sliding back into recession after a brief overall wage growth stalls. Balance sheets side. The one and only regularity of past recovery, or an L-shaped cycle in which have also been hit hard: Some $15 trillion business cycles is that severe downturns the recession is followed by measurably in household wealth has evaporated, the have been followed by strong recoveries, weaker growth for an extended period. federal government has run up deficits and shallow downturns by shallow A W-shaped cycle seems more likely approaching $1.5 trillion, and many state recoveries.2 The 2001 recession was the if policymakers misstep. The last time and local governments have borrowed mildest since World War II—real GDP the economy suffered a double-dip was heavily to fill gaping budget holes. -

Supporting Documents for DSGE Models Update

Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 02/09/2018 BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Division of Monetary Affairs FOMC SECRETARIAT Date: June 11, 2012 To: Research Directors From: Deborah J. Danker Subject: Supporting Documents for DSGE Models Update The attached documents support the update on the projections of the DSGE models. 1 of 1 Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 02/09/2018 System DSGE Project: Research Directors Drafts June 8, 2012 1 of 105 Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 02/09/2018 Projections from EDO: Current Outlook June FOMC Meeting Hess Chung, Michael T. Kiley, and Jean-Philippe Laforte∗ June 8, 2012 1 The Outlook for 2012 to 2015 The EDO model projects economic growth modestly below trend through 2013 while the policy rate is pegged to its e ective lower bound until late 2014. Growth picks up noticeably in 2014 and 2015 to around 3.25 percent on average, but infation remains below target at 1.7 percent. In the current forecast, unemployment declines slowly from 8.25 percent in the third quarter of 2012 to around 7.75 percent at the end of 2014 and 7.25 percent by the end of 2015. The slow decline in unemployment refects both the inertial behavior of unemployment following shocks to risk-premia and the elevated level of the aggregate risk premium over the forecast. By the end of the forecast horizon, however, around 1 percentage point of unemployment is attributable to shifts in household labor supply. -

An Empirical Investigation of the U.S. Gdp Growth: A

AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE U.S. GDP GROWTH: A MARKOV SWITCHING APPROACH Ozge KANDEMIR KOCAASLAN A thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics Date Submitted: January 2013 To my parents ii Abstract This thesis is composed of three separate yet related empirical studies. In Chap- ter 2, we empirically investigate the effects of inflation uncertainty on output growth for the U.S. economy using both monthly and quarterly data over 1960- 2009. Employing a Markov regime switching approach, we show that inflation uncertainty obtained from a Markov regime switching GARCH model exerts a negative and regime dependent impact on growth. We show that the negative impact of inflation uncertainty on growth is almost 2 times higher during the low growth regime than that during the high growth regime. We verify the robustness of our findings using quarterly data. In Chapter 3, we empirically examine whether there are asymmetries in the real effects of monetary policy shocks across business cycle and whether financial depth plays an important role in dampening the effects of monetary policy shocks on output growth using quarterly U.S. data over the period 1981:QI{2009:QII. Applying an instrumental variables estimation in Markov regime switching method- ology, we document that the impact of monetary policy changes on growth is stronger during recessions. We also find that financial development is very promi- nent in dampening the real effects of monetary policy shocks especially during the periods of recession. In Chapter 4, we empirically search for the causal link between energy con- sumption and economic growth employing a Markov switching Granger causality analysis. -

The Prospects for Russian Oil and Gas

Fueling the Future: The Prospects for Russian Oil and Gas By Fiona Hill and Florence Fee1 This article is published in Demokratizatsiya, Volume 10, Number 4, Fall 2002, pp. 462-487 http://www.demokratizatsiya.org Summary In February 2002, Russia briefly overtook Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest oil producer. With its crude output well in excess of stagnant domestic demand, and ambitious oil industry plans to increase exports, Russia seemed poised to expand into European and other energy markets, potentially displacing Middle East oil suppliers. Russia, however, can not become a long-term replacement for Saudi Arabia or the members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in global oil markets. It simply does not have the oil reserves or the production capacity. Russia’s future is in gas rather than oil. It is a world class gas producer, with gas fields stretching from Western to Eastern Siberia and particular dominance in Central Asia. Russia is already the primary gas supplier to Europe, and in the next two decades it will likely capture important gas markets in Northeast Asia and South Asia. Russian energy companies will pursue the penetration of these markets on their own with the strong backing of the State. There will be few major prospects for foreign investment in Russian oil and gas, especially for U.S. and other international companies seeking an equity stake in Russian energy reserves. Background Following the terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, growing tensions in American relations with Middle East states coincided with OPEC’s efforts to impose production cuts to shore-up petroleum prices. -

FPI Pulling Apart Nov 15 Final

Pulling Apart: The Continuing Impact of Income Polarization in New York State Embargoed for 12:01 AM Thursday, Nov. 15, 2012 A Fiscal Policy Institute Report www.fiscalpolicy.org November 15, 2012 Pulling Apart: The Continuing Impact of Polarization in New York State Acknowledgements The primary author of this report is Dr. James Parrott, the Fiscal Policy Institute’s Deputy Director and Chief Economist. Frank Mauro, David Dyssegaard Kallick, Carolyn Boldiston, Dr. Brent Kramer, and Dr. Hee-Young Shin assisted Dr. Parrott in the analysis of the data presented in the report and in the editing of the final report. Special thanks are due to Elizabeth C. McNichol of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Dr. Douglas Hall of the Economic Policy Institute for sharing with us the data from the state- by-state analysis of income trends that they completed for the new national Pulling Apart report being published by their two organizations. This report would not have been possible without the support of the Ford and Charles Stewart Mott Foundations and the many labor, religious, human services, community and other organizations that support and disseminate the Fiscal Policy Institute’s analytical work. For more information on the Fiscal Policy Institute and its work, please visit our web site at www.fiscalpolicy.org. Embargoed for 12:01 AM Thursday, Nov. 15, 2012 FPI November 15, 2012 1 Pulling Apart: The Continuing Impact of Polarization in New York State Highlights In the three decades following World War II, broadly shared prosperity drew millions up from low-wage work into the middle class and lifted living standards for the vast majority of Americans. -

Key Determinants for the Future of Russian Oil Production and Exports

April 2015 Key Determinants for the Future of Russian Oil Production and Exports OIES PAPER: WPM 58 James Henderson* The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2015 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-027-6 *James Henderson is Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. i April 2015 – Key Determinants for the Future of Russian Oil Production and Exports Acknowledgements I would like to thank my colleagues at the OIES for their help with this research and to those who also assisted by reviewing this paper. In particular I am very grateful for the support and comments provided by Bassam Fattouh, whose contribution was vital to the completion of my analysis. I would also like to thank my editor, Matthew Holland, for his detailed corrections and useful comments. Thanks also to the many industry executives, consultants, and analysts with whom I have discussed this topic, but as always the results of the analysis and any errors remain entirely my responsibility. ii April 2015 -

Trends and Patterns of Energy Consumption in India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich RePEc Personal Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Trends and Patterns of Energy Consumption in India Santosh Sahu Indian Institute of Technology Bombay 29. December 2008 Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/16753/ MPRA Paper No. 16753, posted 11. August 2009 23:36 UTC Trends and Patterns of Energy Consumption in India Santosh Kumar Sahu1 1 Introduction Energy has been universally recognized as one of the most important inputs for economic growth and human development. There is a strong two-way relationship between economic development and energy consumption. On one hand, growth of an economy, with its global competitiveness, hinges on the availability of cost-effective and environmentally benign energy sources, and on the other hand, the level of economic development has been observed to be dependent on the energy demand (EIA, 2006). Energy intensity is an indicator to show how efficiently energy is used in the economy. The energy intensity of India is over twice that of the matured economies, which are represented by the OECD (Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development) member countries. India’s energy intensity is also much higher than the emerging economies. However, since 1999, India’s energy intensity has been decreasing and is expected to continue to decrease (GOI, 2001). The indicator of energy–GDP (gross domestic product) elasticity, that is, the ratio of growth rate of energy to the growth rate GDP, captures both the structure of the economy as well as the efficiency. -

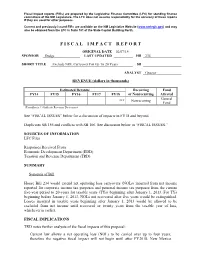

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current and previously issued FIRs are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov) and may also be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/14 SPONSOR Dodge LAST UPDATED HB 234 SHORT TITLE Exclude NOL Carryover For Up To 20 Years SB ANALYST Graeser REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Estimated Revenue Recurring Fund FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 or Nonrecurring Affected General *** Nonrecurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decreases) See “FISCAL ISSUES” below for a discussion of impacts in FY18 and beyond. Duplicates SB 156 and conflicts with SB 106. See discussion below in “FISCAL ISSUES.” SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Economic Development Department (EDD) Taxation and Revenue Department (TRD) SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 234 would extend net operating loss carryovers (NOLs) incurred from net income reported for corporate income tax purposes and personal income tax purposes from the current five-year period to 20-years for taxable years (TYs) beginning after January 1, 2013. For TYs beginning before January 1, 2013, NOLs not recovered after five years would be extinguished. Losses incurred in taxable years beginning after January 1, 2013 would be allowed to be excluded from net income until recovered or twenty years from the taxable year of loss, whichever is earlier.