MONEY TALKS; IDEOLOGY WALKS : Russian Collaborations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927 Ryan C. Ferro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ferro, Ryan C., "Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist-Guomindang Split of 1927 by Ryan C. Ferro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-MaJor Professor: Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Co-MaJor Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Iwa Nawrocki, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2019 Keywords: United Front, Modern China, Revolution, Mao, Jiang Copyright © 2019, Ryan C. Ferro i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…...ii Chapter One: Introduction…..…………...………………………………………………...……...1 1920s China-Historiographical Overview………………………………………...………5 China’s Long -

The Comintern in China

The Comintern in China Chair: Taylor Gosk Co-Chair: Vinayak Grover Crisis Director: Hannah Olmstead Co-Crisis Director: Payton Tysinger University of North Carolina Model United Nations Conference November 2 - 4, 2018 University of North Carolina 2 Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director 3 Introduction 5 Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang 7 The Mission of the Comintern 10 Relations between the Soviets and the Kuomintang 11 Positions 16 3 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to UNCMUNC X! My name is Hannah Olmstead, and I am a sophomore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I am double majoring in Public Policy and Economics, with a minor in Arabic Studies. I was born in the United States but was raised in China, where I graduated from high school in Chengdu. In addition to being a student, I am the Director-General of UNC’s high school Model UN conference, MUNCH. I also work as a Resident Advisor at UNC and am involved in Refugee Community Partnership here in Chapel Hill. Since I’ll be in the Crisis room with my good friend and co-director Payton Tysinger, you’ll be interacting primarily with Chair Taylor Gosk and co-chair Vinayak Grover. Taylor is a sophomore as well, and she is majoring in Public Policy and Environmental Studies. I have her to thank for teaching me that Starbucks will, in fact, fill up my thermos with their delightfully bitter coffee. When she’s not saving the environment one plastic cup at a time, you can find her working as the Secretary General of MUNCH or refereeing a whole range of athletic events here at UNC. -

Eugene Miakinkov

Russian Military Culture during the Reigns of Catherine II and Paul I, 1762-1801 by Eugene Miakinkov A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©Eugene Miakinkov, 2015 Abstract This study explores the shape and development of military culture during the reign of Catherine II. Next to the institutions of the autocracy and the Orthodox Church, the military occupied the most important position in imperial Russia, especially in the eighteenth century. Rather than analyzing the military as an institution or a fighting force, this dissertation uses the tools of cultural history to explore its attitudes, values, aspirations, tensions, and beliefs. Patronage and education served to introduce a generation of young nobles to the world of the military culture, and expose it to its values of respect, hierarchy, subordination, but also the importance of professional knowledge. Merit is a crucial component in any military, and Catherine’s military culture had to resolve the tensions between the idea of meritocracy and seniority. All of the above ideas and dilemmas were expressed in a number of military texts that began to appear during Catherine’s reign. It was during that time that the military culture acquired the cultural, political, and intellectual space to develop – a space I label the “military public sphere”. This development was most clearly evident in the publication, by Russian authors, of a range of military literature for the first time in this era. The military culture was also reflected in the symbolic means used by the senior commanders to convey and reinforce its values in the army. -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee -

The Grand Duke Constantine's Regiment of Cuirassiers of The

Johann Georg Paul Fischer (Hanover 1786 - London 1875) The Grand Duke Constantine’s Regiment of Cuirassiers of the Imperial Russian Army in 1806 signed and dated ‘Johann Paul Fischer fit 1815’ (lower left); dated 1815 (on the reverse); the mount inscribed with title and dated 1806 watercolour over pencil on paper, with pen and ink 20.5 x 29 cm (8 x 11½ in) This work by Johann Georg Paul Fischer is one of a series of twelve watercolours depicting soldiers of the various armies involved in the Napoleonic Wars, a series of conflicts which took place between 1803 and 1815, when Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo. The series is a variation of a similar set executed slightly earlier, held in the Royal Collection, and which was probably purchased by, or presented to, the Prince Regent. In this work, Fischer depicts various elements of the Russian army. On the left hand side, the Imperial Guard stride forward in unison, each figure looking gruff and determined. They are all tall, broad and strong and as a collective mass they appear very imposing. Even the drummer, who marches in front, looks battle-hardened and commanding. On the right-hand side, a cuirassier sits atop his magnificent steed and there appear to be further cavalry soldiers behind him. There is a swell of purposeful movement in the work, which creates an impressive image of military power. The Russian cuirassiers were part of the heavy cavalry and were elite troops as their ranks were filled up with the best soldiers selected from dragoon, uhlan, jager and hussar regiments. -

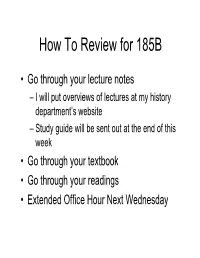

How to Review for 185B

How To Review for 185B • Go through your lecture notes – I will put overviews of lectures at my history department’s website – Study guide will be sent out at the end of this week • Go through your textbook • Go through your readings • Extended Office Hour Next Wednesday Lecture 1 Geography of China • Diverse, continent-sided empire • North vs. South • China’s Rivers RIVERS Yellow 黃河 Yangzi 長江 West 西江/珠江 Beijing 北京 Shanghai 上海 Hong Kong (Xianggang) 香港 Lecture 2 Legacies of the Qing Dynasty 1. The Qing Empire (Multi-ethnic Empire) 2. The 1911 Revolution 3. Imperialisms in China 4. Wordlordism and the Early Republic Qing Dynasty Sun Yat-sen 孙中山 Queue- cutting: 1911 The Abdication of Qing • Yuan Shikai – Negotiation between Yuan (on behalf of the Republican) and the Qing State • Abdication of Qing: Feb 12, 1912 • Yuan became the second provisional president Feb 14, 1912 China’s Last Emperor Xuantong 宣统 (Puyi 溥仪) Threats to China Lecture 3 Early Republic 1. The Yuan Shikai Era: a revisionist history 2. Yuan Shikai’s Rule 3. The Beijing Government 4. Warlords in China Yuan Shikai’s Era The New Republic • The New Election – Guomindang – Progressive Party • The Yuan Shikai Era – Challenges –Problems Beijing Government • Chaotic • Constitutional Warlordism • Militarists? • Cliques under Constitutional Government • The Warlord Era Lecture 4 The New Cultural Movement and the May Fourth 1. China and Chinese Culture in Traditional Time 2. The 1911 Revolution and the Change of Political Culture 3. The New Cultural Movement 4. The May Fourth Movement -

What Do We Read in Soldiers' Letters of Russian Jews from the Great War?

Revue des études slaves LXXXVII-2 | 2016 Sociétés en guerre, Russie - Europe centrale (1914-1918) A war of letters – What do we read in soldiers’ Letters of Russian Jews from the Great War? Une guerre de lettres. Que disent les lettres de soldats juifs de Russie écrites pendant la Grande Guerre ? Alexis Hofmeister Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/res/862 DOI: 10.4000/res.862 ISSN: 2117-718X Publisher Institut d'études slaves Printed version Date of publication: 19 July 2016 Number of pages: 181-193 ISBN: 978-2-7204-05440-0 ISSN: 0080-2557 Electronic reference Alexis Hofmeister, « A war of letters – What do we read in soldiers’ Letters of Russian Jews from the Great War? », Revue des études slaves [Online], LXXXVII-2 | 2016, Online since 26 March 2018, connection on 14 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/res/862 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/res.862 Revue des études slaves A WAR OF LETTERS – WHAT DO WE READ IN SOLDIERS’ LETTERS OF RUSSIAN JEWS FROM THE GREAT WAR? Alexis HOFMEISTER Université de Bâle When the Russian Imperial state-Duma, the nationwide parliament of the Russian empire at the 23rd of July 1914 (old style) discussed the declaration of war by emperor Nicholas II, deputy Naftali Markovich Fridman (1863-1921), one of the few Jewish deputies of the fourth duma declared the unconditional approval of the Russian Jews for the Russian war effort: I have the high honor to express the feeling, which in this historical moment inspires the Jewish people. In the big upheaval, in which all tribes and peoples of Russia take part, the Jews embark too upon the field of battle side by side with all of Russia’s peoples. -

The British and French Representatives to the Communist International, 1920–1939: a Comparative Surveyã

IRSH 50 (2005), pp. 203–240 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859005001938 # 2005 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis The British and French Representatives to the Communist International, 1920–1939: A Comparative Surveyà John McIlroy and Alan Campbell Summary: This article employs a prosopographical approach in examining the backgrounds and careers of those cadres who represented the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Parti Communiste Franc¸ais at the Comintern headquarters in Moscow. In the context of the differences between the two parties, it discusses the factors which qualified activists for appointment, how they handled their role, and whether their service in Moscow was an element in future advancement. It traces the bureaucratization of the function, and challenges the view that these representatives could exert significant influence on Comintern policy. Within this boundary the fact that the French representatives exercised greater independence lends support, in the context of centre–periphery debates, to the judgement that within the Comintern the CPGB was a relatively conformist party. Neither the literature on the Communist International (Comintern) nor its national sections has a great deal to say about the permanent representatives of the national parties in Moscow. The opening of the archives has not substantially repaired this omission.1 From 1920 to 1939 fifteen British communists acted as their party’s representatives to the à This article started life as a paper delivered to the Fifth European Social Science History Conference, Berlin, 24–27 March 2004. Thanks to Richard Croucher, Barry McLoughlin, Emmet O’Connor, Bryan Palmer, Reiner Tosstorff, and all who participated in the ‘‘Russian connections’’ session. -

High Treason: Essays on the History of the Red Army 1918-1938, Volume II

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH TITLE : HIG H TREASON: ESSAYS ON THE HISTORY OF TH E RED ARMY 1918-193 8 VOLUME I I AUTHOR . VITALY RAPOPOR T YURI ALEXEE V CONTRACTOR : CENTER FOR PLANNING AND RESEARCH, .INC . R . K . LAURINO, PROJECT DIRECTO R PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : VLADIMIR TREML, CHIEF EDITO R BRUCE ADAMS, TRANSLATOR - EDITO R COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 626- 3 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or i n part from funds provided by the National Council for Sovie t and East European Research . HIGH TREASO N Essays in the History of the Red Army 1918-1938 Volume I I Authors : Vitaly N . Rapopor t an d Yuri Alexeev (pseudonym ) Chief Editor : Vladimir Trem l Translator and Co-Editor : Bruce Adam s June 11, 198 4 Integrative Analysis Project o f The Center for Planning and Research, Inc . Work on this Project supported by : Tte Defense Intelligence Agency (Contract DNA001-80-C-0333 ) an d The National Council for Soviet and East European Studies (Contract 626-3) PART FOU R CONSPIRACY AGAINST THE RKK A Up to now we have spoken of Caligula as a princeps . It remains to discuss him as a monster . Suetoniu s There is a commandment to forgive our enemies , but there is no commandment to forgive our friends . L . Medic i Some comrades think that repression is the main thing in th e advance of socialism, and if repression does not Increase , there is no advance . Is that so? Of course it is not so . -

An American in the Russian Fighting

Surgeon Grow: An American in the Russian Fighting Laurie S. Stoff The remembrances of Dr. Malcom Grow, an American surgeon who served with the Russian Imperial Army for several years during World War I, serve as a valuable addition to our understanding of the war experiences on the Eastern Front. The war in the East is signifcantly underrepresented in publications on the Great War than that of the Western Front. While one may peruse shelf after shelf of memoirs, journalists’ accounts, and scholarly assessments concerning the participation of Western nations in the First World War, the same cannot be said about Russia’s Great War. Loath to celebrate an imperialist war, in fact, for many, merely perceived as prelude to revolution, the Soviet ofcials failed to engage in extensive ofcial commemoration of the war akin to that of the British and French; Soviet historians similarly shied away from extensive analysis of the confict. Western scholars, as a result of language barriers and general lack of attention to Eastern Europe, tended to focus their histories on Western actors. Russia’s participation in the First World War was thus often overlooked, and ultimately overshadowed by the Revolution, and then, by the devasting impact of the Second World War.1 Nonetheless, the war in Russia deserves considerable attention (and in recent years, has begun to obtain it)2, not only as a result of the fact that it was a primary area of confict, but also because Russia’s Great War was substantively diferent in numerous ways. Perhaps most importantly, the war was far from the stagnant trench warfare along a relatively stable front that characterized the combat in places like France. -

The Rise and Fall of Communism

The Rise and Fall of Communism archie brown To Susan and Alex, Douglas and Tamara and to my grandchildren Isobel and Martha, Nikolas and Alina Contents Maps vii A Note on Names viii Glossary and Abbreviations x Introduction 1 part one: Origins and Development 1. The Idea of Communism 9 2. Communism and Socialism – the Early Years 26 3. The Russian Revolutions and Civil War 40 4. ‘Building Socialism’: Russia and the Soviet Union, 1917–40 56 5. International Communism between the Two World Wars 78 6. What Do We Mean by a Communist System? 101 part two: Communism Ascendant 7. The Appeals of Communism 117 8. Communism and the Second World War 135 9. The Communist Takeovers in Europe – Indigenous Paths 148 10. The Communist Takeovers in Europe – Soviet Impositions 161 11. The Communists Take Power in China 179 12. Post-War Stalinism and the Break with Yugoslavia 194 part three: Surviving without Stalin 13. Khrushchev and the Twentieth Party Congress 227 14. Zig-zags on the Road to ‘communism’ 244 15. Revisionism and Revolution in Eastern Europe 267 16. Cuba: A Caribbean Communist State 293 17. China: From the ‘Hundred Flowers’ to ‘Cultural Revolution’ 313 18. Communism in Asia and Africa 332 19. The ‘Prague Spring’ 368 20. ‘The Era of Stagnation’: The Soviet Union under Brezhnev 398 part four: Pluralizing Pressures 21. The Challenge from Poland: John Paul II, Lech Wałesa, and the Rise of Solidarity 421 22. Reform in China: Deng Xiaoping and After 438 23. The Challenge of the West 459 part five: Interpreting the Fall of Communism 24. -

Sun Yat-Sen and the ROC-PRC Paradox

Not Out of the Blue: Sun Yat-sen and the ROC-PRC Paradox Author: Jacob Throwe Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1976 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2011 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. NOT OUT OF THE BLUE: SUN YAT-SEN AND THE ROC-PRC PARADOX JACOB THROWE BOSTON COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES, HONORS PROGRAM ADVANCED INDEPEDNENT RESEARCH PROJECT CLASS OF 2011 THESIS ADVISOR: DR. REBECCA NEDOSTUP, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SECOND READER: DR. FRANZISKA SERAPHIM, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ‚<let’s always remember this moment; let’s always remember to value and feel gratitude for it, because the fruits of democracy did not come out of the blue.‛ —Chen Shui-bian (May 20, 2000) Contents List of Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Note on Romanization v Preface : An Apparent Paradox 1 I. Father of the Nation 4 1. Sun Yat-sen: The Man Who Would Be Guo Fu 5 2. The Fragile Bond of the First United Front 34 II. Battling Successors 45 3. Chiang Kai-Shek and The Fight over Interpretation 46 4. The Alternative of Mao Zedong 57 III. The Question of Democracy in Greater China 68 5. The Wavering Bond between Taiwan and China 69 6. The Political Transformation on Taiwan 80 Conclusion 93 Bibliography 97 ii Figures 1.1 Inequality (1924) 17 1.2 False Equality (1924) 18 1.3 True Equality (1924) 19 1.4 A Comparative Study of Constitutions (1921) 21 1.5 Powers of the People and Government (1924) 22 1.6 Component Parts of the Five-Power Constitution (1924) 23 5.1 Map of Taiwan 70 iii Acknowledgements It would simply be infeasible to name all the people who helped me complete this project.