Section III: County Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

Native News, September/October 2006

Native News Newsletter of the Maryland Native Plant Society September/October 2006 Volume 6 Number 5 Inside This Issue: Upcoming Monthly Meetings President’s Letter Page 2 “Goldenrods, Asters, and Thoroughworts” ~ Tuesday, September 26, 7:30 pm MNPS Contacts White Oak Library – Large Meeting Room Page 2 ~ The Asteraceae (Aster Family) is a large and diverse family that is MNPS Announcements especially well-developed in North America. Maryland and the mid- Page 3 Atlantic region are home to a particularly rich diversity of native plants ~ in the Aster Family. Join botanist Rod Simmons for an in-depth Upcoming Chapter Events Page 3 presentation of the many native species of Solidago, Eupatorium, and ~ Aster (formerly) in Maryland. The talk will focus on identification of Wildflower in Focus the common species, but will also include uncommon and rare ones Page 4 and habitats throughout the state where they may be found. Live plant ~ material will be available for hands-on identification. Late Summer/Fall Field Trips Page 5 “The Importance of Hybridization in the ~ Invasive Exotic Plant Systematic Evolution of Oaks” Removal Workdays Tuesday, October 24, 7:30 pm Page 6 White Oak Library – Large Meeting Room ~ General Announcements The oaks are one of North America’s most widespread and important Page 7 trees. Nearly 80 native species of oaks occur in North America, not including the numerous natural hybrids and app. 100 species in Mexico. Maryland is one of the most diverse areas in the east for oaks, with 21 of the 41 oak species native to the eastern U.S., not including hybrids. -

The Heron's Flight

16 The Heron’s Flight The Heron’s Flight is not a linear trail. Instead, a cluster of sites near the center of Charles County forms the core, and various offshoots branch out to the water’s edge in all directions. The first five sites (the core of this Trail) are in La Plata’s downtown on Charles Street and St. Mary’s Avenue; they are all within walking distance of each other, although parking is readily available. 1 Charles Street Bakery & Cafe 507 East Charles Street, La Plata A perfect beginning to any Trails trip, latte drinks and deli- cious pastries by owner Deborah Taylor will ensure you’re energized and ready to meet the day. Her baked goods are made with local eggs and fruit when possible. Take home a treat for your family or guests, or join the “regulars” who lunch here. Her specialty is wedding cakes if the need arises. Open Mon. – Fri. 6 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., Sat. 6 a.m. to 4 p.m. (301) 392-6344, www.charlesstreetbakery.com www.somdtrails.com On Charles Street in downtown La Plata. 2 Bernie’s Frame Shop 205 East Charles Street, La Plata Tucked away in this busy frame shop are some delightful surprises…original paintings, photos and prints by area artists and handmade furniture by a Southern Maryland woodworker. Locals have long known that this is the place to go for a meaningful gift for a retiring co-worker, graduat- ing senior or good friend who is leaving the area. Purchase a framed piece, or get something from the print bin and Explore a new owner Debora Almassy will help you decide on the perfect interactive map of mat and frame. -

News and Notes Prince George's County J § 'W

News and Notes Prince George's County J § 'W . CO , Historical Society ! = = 3 e 'MaritlU' February 1997 Our 45th Year Volume XXV Number 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1997 President - Jane Eagen Directors 1997-1999 Past Presidents Vice President - Eugene Roberts, Jr. Mildred Ridgeley Gray John Giannetti Secretary - Sarah Bourne Melinda Alter Paul T. Lanham Treasurer - John Bourne Katherine Clagett Warren Rhoads Historian - Frederick DeMarr Directors 1996-1998 W.C. (Bud) Button Editor - Sharon Howe Sweeting Julie Bright Joyce MacDonald John Mitchell William Uber Illustration by Fred H. Greenberg from Washington Itself by E. J. Applewhite, 1986 JOIN US on SATURDAY, MARCH 8 at 2:00 pm at the Glenn Dale Community Center Mr David J. Danelski, Supreme Court Historian, will speak on Sons of Maryland on the United States Supreme Court: Thomas Johnson, Samuel Chase, Gabriel Duvall, Roger Brooke Taney and Thurgood Marshall. Mr. Danelski has researched, taught and written extensively about the United States Supreme Count. He will share little know stories and attempt to undo some popular misconceptions about these men. We have invited the members of the Duvall Society to join us for this celebration of Gabriel Duvall. The reception following the program will be at Marietta, home of Gabriel Duvall. FROM THE EDITOR'S DESK Happy New Year. You will notice on the cover the new/old Board of Directors of the Historical Society and an announcement of the meeting on Saturday, March 8 (2:00 pm, Glenn Dale Community Center) on "Sons of Maryland on the United States Supreme Court." This issue begins with the continuation of a column called Meet the Meet the Board Board written by Secretary Sarah Bourne. -

Purpose of Bicycling Trips Such As Recreation, Leisure, Exercise, Personal Errands and Commuting Are Shown in the Figure 3-2

April 10, 2012 Mission Statement: The mission of Charles County Government is to provide our citizens the highest quality service possible in a timely, efficient, and courteous manner. To achieve this goal, our government must be operated in an open and accessible atmosphere, be based on comprehensive long- and short-term planning, and have an appropriate managerial organization tempered by fiscal responsibility. Vision Statement: Charles County is a place where all people thrive and businesses grow and prosper; where the preservation of our heritage and environment is paramount; where government services to its citizens are provided at the highest level of excellence; and where the quality of life is the best in the nation. Acknowledgements County Commissioners of Charles County Candice Quinn Kelly President Reuben B. Collins, II, Esq. Vice President Ken Robinson Debra M. Davis, Esq. Bobby Rucci District 1 District 2 District 4 Charles County Planning Commission Courtney Joseph Edmonds, Esq. Joseph D. Richard Chairman Vice Chairman Robert E. Mitchell Secretary Stephen M. Bunker Louis D. Grasso Joan Jones Joseph E. Tieger Charles County Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan April 10, 2012 Acknowledgements (Continued) Rebecca B. Bridgett, Ed.D. County Administrator Charles County Government Department of Planning and Growth Management Peter Aluotto, AICP Director Steven Ball, AICP, LEED AP Planning Director Cathy Thompson Community Planning Program Manager Beth Groth Planner II Stakeholders National Park Service Oxon Hill Bike Club Accokeek -

Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Connecting

CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH CHESAPEAKE NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL CONNECTING TRAILS EVALUATION STUDY 410 Severn Avenue, Suite 405 Annapolis, MD 21403 CONTENTS Acknowledgments 2 Executive Summary 3 Statement of Study Findings 5 Introduction 9 Research Team Reports 10 Anacostia River 11 Chester River 15 Choptank River 19 Susquehanna River 23 Upper James River 27 Upper Nanticoke River 30 Appendix: Research Teams’ Executive Summaries and Bibliographies 34 Anacostia River 34 Chester River 37 Choptank River 40 Susquehanna River 44 Upper James River 54 Upper Nanticoke River 56 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are truly thankful to the research and project team, led by John S. Salmon, for the months of dedicated research, mapping, and analysis that led to the production of this important study. In all, more than 35 pro- fessionals, including professors and students representing six universities, American Indian representatives, consultants, public agency representatives, and community leaders contributed to this report. Each person brought an extraordinary depth of knowledge, keen insight and a personal devotion to the project. We are especially grateful for the generous financial support that we received from the following private foundations, organizations and corporate partners: The Morris & Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, The Clay- ton Fund, Inc., Colcom Foundation, The Conservation Fund, Lockheed Martin, the Richard King Mellon Foundation, The Merrill Foundation, the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, the Rauch Foundation, The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation, Verizon, Virginia Environmental Endowment and the Wallace Genetic Foundation. Without their support this project would simply not have been possible. Finally, we would like to extend a special thank you to the board of directors of the Chesapeake Conser- vancy, and to John Maounis, Superintendent of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Office, for their leadership and unwavering commitment to the Captain John Smith Chesapeake Trail. -

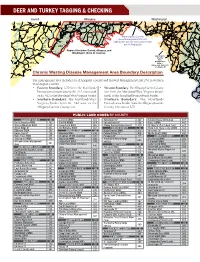

Deer and Turkey Tagging & Checking

DEER AND TURKEY TAGGING & CHECKING Chronic Wasting Disease Management Area Boundary Description The management area includes all of Allegany County and Harvest Management Unit 250 in western Washington County. • Eastern Boundary: I-70 from the Maryland/ • Western Boundary: The Allegany/Garrett County Pennsylvania border south to Rt. 522, then south line from the Maryland/West Virginia border on Rt. 522 to the Maryland/West Virginia border. north to the Maryland/Pennsylvania border. • Southern Boundary: The Maryland/West • Northern Boundary: The Maryland/ Virginia border from Rt. 522 west to the Pennsylvania border from the Allegany/Garrett Allegany/Garrett County line. County line east to I-70. PUBLIC LAND CODES BY COUNTY ALLEGANY COUNTY 01 Earleville WMA 363 Gunpowder SP 327 Patuxent Naval Air Station 465 Dan’s Mountain WMA 240 Fair Hill NRMA 364 Susquehanna SP 328 Elm’s CWMA 466 Warrior Mountain WMA 241 Grove Farm WMA 366 Stoney Demonstration Forest 329 St. Mary’s SP or Salem Tract 467 Green Ridge SF 242 Old Bohemia WMA 367 HOWARD COUNTY 13 Historic St. Mary’s City CWMA 468 Billmeyer WMA 243 CHARLES COUNTY 08 Hugg-Thomas WMA 415 Greenwell SP 469 Rocky Gap SP 244 Riverside WMA 395 Patuxent River SP 416 Myrtle Point CWMA 600 Belle Grove WMA 245 Chapman SP (Mt. Aventine) 397 Patapsco SP 417 SOMERSET COUNTY 19 Sideling Hill WMA 246 Nanjemoy WMA 398 Triadelphia/Rocky Gorge Deal Island WMA 500 604 McCoole Fishery Management Cedar Point WMA 399 (WSSC) Fairmount WMA 501 247 Indian Head Naval Ordinance Cedar Island WMA 503 Area 400 KENT COUNTY -

Area's #1 Fishing & Hunting Outfitter

Dear Angler: Here in Maryland, we need only look to our State Seal — depicting the fisherman and the ploughman — for proof that fishing really is part of our heritage. It’s a fun, affordable and accessible activity for all ages, and a great excuse to get our children away from video and computer games and into the great outdoors! Approximately 700,000 adults and thousands of young people fish each year in Maryland, with an estimated annual impact of $1 billion on our economy. Gov. Martin O’Malley and Sec. John R. Griffin More than a third of our anglers visit from out of state, testimony to the value and quality of our great fishing resources. We are very fortunate to have expert biologists and managers – working to- gether with our Sport Fisheries, Tidal Fisheries and Oyster Advisory Commissions, and our Coastal Fisheries Advisory Committee, to guide fisheries management across our State. We are also very fortunate to have you -- committed conserva- tionists and advocates – working with us. Your license revenues support protection and enhancement of Maryland’s fishery resources, research and management activities, expanded public access and enhanced law enforcement. And we look forward to strengthening our partnership with you as we work toward our goals for a restored Chesapeake Bay, thriving freshwater streams, and healthy abundant fish populations. Thank you for being a part of a great cultural tradition, and here’s wishing you a terrific year of fishing in Maryland. Martin O’Malley John R. Griffin Governor Secretary About the Cover: This edition of the Maryland Fishing Guide is dedicated to Frances McFaden, who retired from public service after 43 years as a steadfast, ever-helpful, and resourceful Maryland state worker. -

Digest of Testimony of the Joint Public Hearing September 27, 2016 With

Prince George’s County Preliminary Resource Conservation Plan DIGEST OF TESTIMONY Joint Public Hearing September 27, 2016 with Planning Board Actions The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission Prince George’s County Planning Department pgplanning.org Planning Board District Council Testimony Speaker/Exhibit Discussion/Staff Recommendation Action Action General Comments 1 Topic: Overall support of the plan. Discussion: Planning Board concurs with staff “The City Council supports the Plan’s objectives, policies and Exhibit 28 N/A recommendation. strategies, and appreciates the opportunity to provide comment.” G. Frederick Robinson Staff Recommendation: Mayor for Bowie No change to the plan. City Council “We find the Conservation Plan consistent with the planning Exhibit 29 principles and policies of NCPC’s Comprehensive Plan for the Marcel Acosta National Capital: Federal Elements (Comprehensive Plan). The Executive Director Conservation Plan goals, including enhancing water quality, tree National Planning coverage, and designated viewsheds reinforces multiple policies Capital in the Environment, Parks and Open Space; and Historic Commission Preservation Elements of the Comprehensive Plan.” “The RCP is a comprehensive plan that recognizes the Exhibit 30 importance of protecting the natural resources within the county. Steven E. Darcy The plan strives to strike a balance between growth, conservation District Manager and preservation of the county’s significant rural character. The Prince George’s plan suggests actions to maintain and indeed improve the Soil Conservation sustained economic growth of the county. Connectivity of green District spaces, forestland and agricultural land suggested by the RCP strives to provide a process to economic growth, sustainability and improved quality of life. -

Maryland Land Preservation and Recreation Plan 2014-2018

Maryland Land Preservation and Recreation Plan 2014-2018 Dear Citizens: Our land is the foundation of our economic and social prosperity, rich in productive forests and farms, vital wildlife habitat, opportunities for recreation and tourism, culture and history. As our State grows and changes, it is important to continually evaluate our mission and investments for the benefit of Maryland and its citizens. As champion of public land conservation and outdoor recreation, DNR is pleased to present the Land Preservation and Recreation Plan for 2014-2018 — a comprehensive, statewide plan that will guide our efforts to conserve open space and enhance outdoor resources on State lands for the next five years. Outlining clear goals and measurable action items, the Plan will enhance coordination among local, County and State planners; promote the benefits of outdoor recreation and natural resources; improve access to land and water-based recreation for every Marylander; and connect public trails and lands to the places where people work, live and play. This Plan was developed in cooperation with State, County and local officials, stakeholders and citizens in accordance with the U.S. Department of Interior, Land and Water Conservation Fund guidelines. By helping direct preservation to priority lands and fostering a greater connection to the outdoors, it supports the benefits of health and recreation, economic vitality and environmental sustainability for all citizens. Sincerely, Martin O’Malley Joseph P. Gill Governor Secretary THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Maryland Land Preservation and Recreation Plan 2014-2018 “Connecting People & Places” Honorable Martin J. O’Malley, Governor State of Maryland Joseph P. -

Final DRAFT - Public Environmental Conditions Report Louise F

Final DRAFT - Public Environmental Conditions Report Louise F. Cosca Regional Park January 2021 LOUISE F. COSCA REGIONAL PARK ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS REPORT Prepared For: M-NCPPC Cosca Regional Park 11000 Thrift Road Clinton, MD 20735 Prepared By: Environmental Systems Analysis, Inc. 2141 Priest Bridge Drive, Suite 1 Crofton, MD 21114 FINAL DRAFT FOR PUBLIC VIEW JANUARY 2021 Environmental Conditions Report Cosca Regional Park Master Park Development Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Methods .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Results .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Forest Stands/Natural Communities ..................................................................................................... 3 Forest Stand #1 - Mature Mixed Hardwoods ................................................................................... 5 Forest Stand #2 - Forested Floodplain and Bottomlands ................................................................... 7 Forest Stand #3 – Mid-Seral Disturbed ............................................................................................. 7 Site Soils ............................................................................................................................................ -

Part B Guidelines for the Preparation of a Natural Resource Inventory

Part B Guidelines for the Preparation of a Natural Resource Inventory 1.0 INTRODUCTION A Natural Resources Inventory (NRI), as defined in Subtitles 24 and 27 is: “A plan map and supporting documentation or letter that provides all required information regarding the existing physical and environmental conditions on a site that is approved by the Planning Director or designee as described in the Environmental Technical Manual as approved and amended from time to time.” An NRI is a detailed inventory of the lots or parcels or combination of lots and parcels that will be the subject of a development application. It provides detailed information on the land, ecological resources, and hydrologic resources, as well as any existing structural features of a site. The primary purpose of an NRI is to provide a base plan to be used in the design of the site for land development proposals. It is also used by regulatory agencies for review with various development applications. There are five (5) types of NRIs; however, an NRI is not a substitute, exemption or waiver from the requirements of Subtitle 25, Division 2, Woodland and Wildlife Habitat Conservation Ordinance (WCO). 1.1 NRI APPLICABILITY The following provides clarification of the types of applications that do and do not require a NRI. 1.1.1 Applications That DO Require Submittal of a NRI An approved NRI is required to be included in the following applications: • Preliminary Plan of Subdivision • Chesapeake Bay Critical Area Conservation Plan • Type 2 Tree Conservation Plan applications to establish a Woodland Conservation Bank • Stormwater Management IF the project does not meet the criteria listed in section 1.1.2.