Chapter 19: the Leariad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

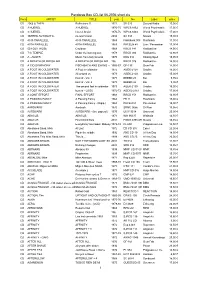

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Rihanna – Rihanna 777 Tour… 7Countires7days7shows DVD • Jay Sean – Neon • Jessica Sanchez

Rihanna – Rihanna 777 Tour… 7countires7days7shows DVD Jay Sean – Neon Jessica Sanchez – Me, You & The Music New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI13-20 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final The Following titles will move to I Code effective FRIDAY, APRIL 12, 2013 Artist Title Catalog UPC Price Code New Number (Current) Price Code GN'R LIES GEFMD24198 720642419823 N I GAYE MARVIN WHAT'S GOING 4400640222 044006402222 N I ON(REMASTERED URIAH HEEP DEMONS & WIZARDS 8122972 042281229725 N I SOUNDTRACK A NIGHT AT THE DRSSD50033 600445003323 SP I ROXBURY ROTH, ASHER ASLEEP IN THE BREAD B001281202 602527018355 SP I AISLE MELLENCAMP AMERICAN FOOL B000418902 602498801376 N I JOHN (COUGAR) MANOWAR LOUDER THAN HELL GEFSD24925 720642492529 SP I MALMSTEEN TRILOGY 8310732 042283107328 N I YNGWIE CRAZY FROG PRESENTS MORE CRAZY B000714902 602517018839 N I HITS ONYX BACDAFUCUP 3145234472 731452344724 N I MALMSTEEN RISING FORCE 8253242 042282532428 N I YNGWIE YOUNG NEIL OLD WAYS 0694907052 606949070526 N I MELLENCAMP SCARECROW B000451202 602498812396 N I JOHN (COUGAR) REDMAN DARE IZ A DARKSIDE 3145238462 731452384621 N I 3 DOORS DOWN ANOTHER 700 MILES B000160302 602498612477 AW I (LIVE) BON JOVI JON BLAZE OF GLORY 8464732 042284647328 N I MENDES GREATEST HITS CD3258 075021325821 N I SERGIO RICHIE LIONEL DANCING ON THE 4400383002 044003830028 N I CEILING (RE BIRDMAN FAST MONEY B000422002 602498801918 SP I SOUNDTRACK XANADU‐REMASTERED -

Late Sixties Rock MP3 Disc Two Playlist.Pdf

Late Sixties Rock MP3 Disc Two Playlist Page One Of Three Title Artist Album 01 - Keep on Chooglin’ Creedence Clearwater Revival Bayou Country 02 - Voodoo Child (Slight Return) The Jimi Hendrix Experience Electric Ladyland 03 - Babe I’m Gonna Leave You Led Zeppelin Led Zeppelin I 04 - Move Over Janis Joplin Pearl 05 - Se a Cabo Santana Abraxas 06 - That Same Feelin’ Savoy Brown Raw Sienna 07 - Plastic Fantastic Lover Jefferson Airplane Surrealistic Pillow 08 - My Guitar Wants to Kill Your Mama Frank Zappa Single 09 - Sparks The Who Tommy 10 - Girl with No Eyes It's A Beautiful Day It's A Beautiful Day 11 - As You Said Cream Wheels of Fire 12 - Different Drum Linda Ronstadt & the Stone Poneys Evergreen, Volume 2 13 - These Boots Are Made for Walkin’ Nancy Sinatra Boots 14 - Iron Butterfly Theme Iron Butterfly Heavy 15 - Summertime Blues Blue Cheer Vincebus Eruptum 16 - Mississippi Queen Mountain Climbing! 17 - Working on the Road Ten Years After Cricklewood Green 18 - On the Road Again Canned Heat Boogie with Canned Heat! 19 - Freedom Richie Havens Woodstock 20 - Déjà Vu Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Déjà Vu 21 - The Best Way to Travel The Moody Blues In Search of the Lost Chord 22 - Big Yellow Taxi Joni Mitchell Ladies of the Canyon 23 - If 6 Was 9 The Jimi Hendrix Experience Axis: Bold as Love 24 - Unconscious Power Iron Butterfly Heavy 25 - Break on Through (To the Other Side) The Doors The Doors 26 - I Feel Free Cream Fresh Cream 27 - I’m Free The Who Tommy 28 - Try (Just a Little Bit Harder) Janis Joplin I Got Dem 0l’ Kozmic Blues -

Selected Chronology of Political Protests and Events in Lawrence

SELECTED CHRONOLOGY OF POLITICAL PROTESTS AND EVENTS IN LAWRENCE 1960-1973 By Clark H. Coan January 1, 2001 LAV1tRE ~\JCE~ ~')lJ~3lj(~ ~~JGR§~~Frlt 707 Vf~ f·1~J1()NT .STFie~:T LA1JVi~f:NCE! i(At.. lSAG GG044 INTRODUCTION Civil Rights & Black Power Movements. Lawrence, the Free State or anti-slavery capital of Kansas during Bleeding Kansas, was dubbed the "Cradle of Liberty" by Abraham Lincoln. Partly due to this reputation, a vibrant Black community developed in the town in the years following the Civil War. White Lawrencians were fairly tolerant of Black people during this period, though three Black men were lynched from the Kaw River Bridge in 1882 during an economic depression in Lawrence. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1894 that "separate but equal" was constitutional, racial attitudes hardened. Gradually Jim Crow segregation was instituted in the former bastion of freedom with many facilities becoming segregated around the time Black Poet Laureate Langston Hughes lived in the dty-asa child. Then in the 1920s a Ku Klux Klan rally with a burning cross was attended by 2,000 hooded participants near Centennial Park. Racial discrimination subsequently became rampant and segregation solidified. Change was in the air after World "vV ar II. The Lawrence League for the Practice of Democracy (LLPD) formed in 1945 and was in the vanguard of Post-war efforts to end racial segregation and discrimination. This was a bi-racial group composed of many KU faculty and Lawrence residents. A chapter of Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) formed in Lawrence in 1947 and on April 15 of the following year, 25 members held a sit-in at Brick's Cafe to force it to serve everyone equally. -

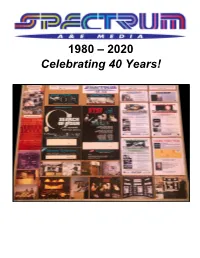

Spectrum History W. Visuals

1980 – 2020 Celebrating 40 Years! Spectrum A&E Media 1980-2020 Celebrating 40 Years! Spectrum Productions was established in 1980 in Regina, Saskatchewan to provide multimedia resources for organizations working with students in Canada. A board of committed friends sacrificially stood behind Keith and Jenny Martin to help raise support and give direction to the work. Spectrum’s Roots The roots of Spectrum go back to 1970, when Keith, having graduated with a B.A. in psychology and a minor in philosophy from the University of Regina, spent time at L’Abri Fellowship in Switzerland. L’Abri was and still is a live-in student community founded by Francis and Edith Schaeffer to explore answers to basic philosophical questions from a Christian worldview. 2 In 1971 Keith, Steve Archer and Art Pearson applied for and received a federal Opportunities For Youth grant for a summer project called Street Level: A Multimedia Culture Probe. Inspired by seeing 2100 Productions in the United States, they wanted to do something similar in Canada. With a budget of $8,800 they hired 8 students (Keith, Steve, Art, Gene Haas, Chris Molnar, Steve and Lorne Seibert, and Linda McArdell—and Henry Friesen for the presentation phase) at $1,000 each for 3 months of work. That left $800, and lots of borrowed eQuipment, to produce a 5-screen, 7-projector 80 minute multi-media presentation using contemporary music to look at what people were living for. 3 Some of the artists used in the production were Pink Floyd, Simon & Garfunkle, Strawbs, STREET LEVEL Steppenwolf, Leonard Cohen, Cat Stevens, Moody Soundtrack (1971) Blues, Traffic, Chicago, Procol Harem, Black “Careful With That Axe, Eugene” - Pink Floyd (Ummagumma) “At the Zoo” - Simon & Garfunkle (Bookends) “I’ve Got a Story” - Gary Wright (Extraction) Sabbath, King Crimson, and Ford Theatre. -

ELCOCK-DISSERTATION.Pdf

HIGH NEW YORK THE BIRTH OF A PSYCHEDELIC SUBCULTURE IN THE AMERICAN CITY A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By CHRIS ELCOCK Copyright Chris Elcock, October, 2015. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History Room 522, Arts Building 9 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada i ABSTRACT The consumption of LSD and similar psychedelic drugs in New York City led to a great deal of cultural innovations that formed a unique psychedelic subculture from the early 1960s onwards. -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

Shawyer Dissertation May 2008 Final Version

Copyright by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 Committee: Jill Dolan, Supervisor Paul Bonin-Rodriguez Charlotte Canning Janet Davis Stacy Wolf Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2008 Acknowledgements There are many people I want to thank for their assistance throughout the process of this dissertation project. First, I would like to acknowledge the generous support and helpful advice of my committee members. My supervisor, Dr. Jill Dolan, was present in every stage of the process with thought-provoking questions, incredible patience, and unfailing encouragement. During my years at the University of Texas at Austin Dr. Charlotte Canning has continually provided exceptional mentorship and modeled a high standard of scholarly rigor and pedagogical generosity. Dr. Janet Davis and Dr. Stacy Wolf guided me through my earliest explorations of the Yippies and pushed me to consider the complex historical and theoretical intersections of my performance scholarship. I am grateful for the warm collegiality and insightful questions of Dr. Paul Bonin-Rodriguez. My committee’s wise guidance has pushed me to be a better scholar. -

Poetics of Protest: a Fluxed History of the 1968 DNC (A Dialogue for Six Academic Voices)

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 8, No. 4, September 2012 Poetics of Protest: A Fluxed History of the 1968 DNC (A Dialogue for Six Academic Voices) Tom Lavazzi Commentator/Over Voice (CO; as described below)/Conductor (“Panel Chair”) Documents (“objective”) Fluxedout (Fluxed; Fluxus attitude) New Historical Left (NHL; based on “old” and “new” New Left and New Historicist voices) The Institute for Cultural Studies (TICS; an institutionalized postmodern academic voice) Yippedout (Yipped; Yippie! Doubling occasionally as “Lecturer”) Poetics of Protest is staged as a typical (atypical) academic conference panel presentation. At the front of the room are two long tables, one for the panelists and another for props. Props overflowing the table may also be ranged around the room, redeploying chalkboard ledges, windowsills, and floor margins, marking the space’s boundaries. Redeployed, theoretically fortified cereals (i.e., empty boxes)—Zizek 0sTM, Blau PopsTM, Lucky Deleuze, Baudrillard PuffsTM, Foucault Flakes, etc.—are suspended from the ceiling. There is also a podium, a data projector and projection screen1 displaying an interactive image map of Chicago, circa 1968, highlighting the Amphitheatre and key riot and protest sites, and, optionally, a video monitor on which the audience may view muted interviews with Yippies. Projected on the podium and the floor directly in front of the podium—slow motion and stop-action scenes from Brett Morgen’s animated documentary of the Chicago 8 trial, Chicago 102; the panelists pause, at intervals, to act out—or rather, act with, re-act (to), comment on via serial tableau vivant--fragments of these scenes, Tom Lavazzi is Professor of English at KBCC-CUNY. -

'Reality Sandwich9 Some '60S Yippies in King Reagan's Court

Inside Reagan rewrites history .. P. 4 Music around town . P. 7 Spikers lose in Denver... P. 9 Vol. 27, No. 23, November 23, 1982 'Reality Sandwich9 Some '60s Yippies in King Reagan's court by Jane Rider especially taboo for that time reality you have to confront," he of The Post staff period." said. Currently living in San Fran What happens when you take Alternative lifestyle cisco, Krassner said, "New York two '60s political activists and put Krassner was also co-rjpunder of is getting more and more bizarre them in front of an '80 college the Yippies, which stood for Youth because they're letting more audience? International Party. people out of mental hospitals. To answer that question, you "We showed an alternative life Students there formed an organi would have had to attend the style and made a joke out of the zation for apathy but had to "Reality Sandwich" served Thurs two party system," he said. "It disband because too many people day night in the UWM ballroom. consisted of an organic coalition of were interested." Paul Krassner, a stand-up psychedelic dropouts, the "new comedian and co-founder of the left" political activists. Willing to take chances Yippies, and Country Joe Mc "The word itself had a double Krassner, however, doesn't see Donald, musician and anti- meaning. It represented the politi things much saner in San Francis Vietnam war leader, both created cal activist party and was a new co. their own post-war political rally. word expressing celebration — "People there know yoga so well The audience responded by laugh Yippie!" they can give themselves head ing, singing, clapping and asking The concept of reality is a loss and herpes at the same time. -

Interview with Anita Hoffman

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Browse All Oral History Interviews Oral History Program 11-28-1992 Interview with Anita Hoffman Anita Hoffman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/oralhistoryprogram Part of the Oral History Commons Recommended Citation Sixties Radicals, Then and Now: Candid Conversations with Those Who Shaped the Era © 2008 [1995] Ron Chepesiuk by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. www.mcfarlandpub.com. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Oral History Program at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse All Oral History Interviews by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOUISE PETTUS ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Interview #236 HOFFMAN, Anita HOFFMAN, Anita Anti-war activist, feminist, poverty awareness activist, scholar Interviewed: November 28, 1992 Interviewer: Ron Chepesiuk Index by: Alyssa Jones Length: 1 hour, 50 minutes, 7 seconds Abstract: In her November 1992 interview with Ron Chepesiuk, Anita Hoffman detailed her experiences in the 1960s and her time with her ex-husband, Abbie Hoffman. Hoffman, aside from speaking about her ex-husband, covered such topics as poverty, racism, the Weathermen (Weather Underground), the Black Panthers and the Black Power movement, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Women’s Liberation, and the Youth International Party. Hoffman also discussed sexism, mental illness, in reference to Abbie and her studies as a Psychology major, the Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill hearings, and the technology revolution. This interview was conducted for inclusion into the Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections Oral History Program. -

Books for Independent Minds to Educate Our Mission Is to Publish Books That Foster Independent and Inform Only

RONIN Catalog $2 RONINBooks BOOKS-FOR-INDEPENDENT-MINDS for Independent Minds Ronin Publishing, Inc., is an independent press in Leary. “Life Skills—With Attitude” include books that tell Berkeley, California, publishing books as tools for per- how to thrive in a changing world, become more autono- sonal empowerment and expanded consciousness. Our mous and find work you love doing. “Fringe Series” keeps name is inspired by the Japanese word for unindentured you informed about things off the grid. “EntheoSpiritual- or maverick samurai, called ronin or “wave men,” be- ity” shows how to find your God within. cause they were cast onto the chaotic waves of change. Ronin sells Books for Independent Minds to educate Our mission is to publish books that foster independent and inform only. We do not advocate breaking the law, thought and empower the individual to become self- including the use of drugs or harming persons or property. mastering and surf the waves. We make no warranties. Get our books at your local bookstore to save on shipping fees, and support your local bookseller. If you See the Terms of Sale (page 16) and our Order Form can’t get books at a nearby store, you can order for complete information. If you are under 18, please do Ronin Please respect other customers’ from amazon.com, b&n.com or directly from us. Check not call or place orders. our website for lastest online catalog. concerns and our position on this issue. We are not inter- “Psychobotanicals” encompasses psychedelics ested in sending our catalog or books to minors.