One False Move for Years, Investing Legend DAVID BONDERMAN Could Do No Wrong. and Then He Tried to Buy a Utility from Enron. By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When We Unite

When We Unite 2020 Gratitude Report Letter from Leadership 2020 was a year unlike any other 02 as a global pandemic took hold, climate change picked up speed, racial injustice reached a new breaking point and a pivotal election consumed the nation. Our Refocused Mission: uniting people 04 to protect America’s wild places But in the face of extraordinary challenges, we understood that backing down wasn’t an option—and that when we unite, we hold the power to build solutions 06 Making Enduring Progress for a flourishing future that’s shared by all. In a critical year when the world felt the full weight of mounting crises, you Solving Urgent Crises 10 showed what it could look like when we come together, find common ground and take bold action to fulfill the promise of public lands for all. 14 Fulfilling the Promise of Public Lands for All 18 Our Supporters 38 Financials 40 The Wilderness Society Action Fund Cover image: Red Cliffs National Conservation Area, Utah Canyonlands National Park, Utah Michelle Craig Benj Wadsworth 1 In particular, we acknowledged Indigenous peoples as the longest 2020: Battling current threats serving stewards of the land and increased our efforts to seek their and charting the course for guidance and partnership in ways that share power, voice and impact. In 2020, we joined forces with more partners than ever before to transformational change ensure that public lands equitably benefit all people, that their potential to help address the great crises facing our nation are After four very challenging years for conservation, hope for a unleashed, and that we unite in a more inclusive and far more powerful sustainable future was renewed in November 2020 by the election conservation movement. -

Annual Report 2017

IDEAS LEADERSHIP ACTION OUR MISSION 2 Letter from Dan Porterfield, President and CEO WHAT WE DO 6 Policy Programs 16 Leadership Initiatives 20 Public Programs 26 Youth & Engagement Programs 30 Seminars 34 International Partnerships 38 Media Resources THE YEAR IN REVIEW 40 2017-2018 Selected Highlights of the Institute's Work 42 Live on the Aspen Stage INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT 46 Capital Campaigns 48 The Paepcke Society 48 The Heritage Society 50 Society of Fellows 51 Wye Fellows 52 Justice Circle and Arts Circle 55 Philanthropic Partners 56 Supporters STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 90 2017 Annual Report WHO WE ARE 96 Our Locations 98 Aspen Institute Leadership 104 Board of Trustees LETTER FROM DAN PORTERFIELD, PRESIDENT AND CEO A LETTER FROM PRESIDENT AND CEO DAN PORTERFIELD There is nothing quite like the Aspen Institute. It is In the years to come, the Aspen Institute will deepen an extraordinary—and unique—American institution. our impacts. It is crucial that we enhance the devel- We work between fields and across divides as a opment of the young, address the urgent challenges non-profit force for good whose mission is to con- of the future, and renew the ideals of democratic so- vene change-makers of every type, established and ciety. I look forward to working closely with our many emerging, to frame and then solve society’s most partners and friends as we write the next chapter on important problems. We lead on almost every issue the Institute’s scope and leadership for America and with a tool kit stocked for solution-building—always the world. -

The Man Who Built a Billion Dollar Fortune Off Pirates of The

February 22, 2019 The Man Who Built a Billion‐Dollar Fortune Off ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ By Tom Metcalf ‘Top Gun’ producer joins Spielberg, Lucas in billionaire club CSI and ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ franchises drive fortune Johnny Depp as Captain Jack Sparrow and Jerry Bruckheimer Photographer: Mark Davis/Getty Images While the glitz and glamour of show business will be on full display Sunday at the Academy Awards, one of Hollywood’s most successful producers will be merely a bystander this year. Don’t weep for Jerry Bruckheimer, however. The man behind classic acon films like “Top Gun” and “Beverly Hills Cop” has won a Hollywood status far rarer than an Oscar ‐‐ membership in the three‐comma club. While stars sll reap plenty of income, the real riches are reserved for those who control the content. The creaves who’ve vaulted into the ranks of billionairedom remains thin, largely the preserve of household names like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, who had the wherewithal to enter film producon and se‐ cured rights to what they produced. Bruckheimer has been just as successful on the small screen, producing the “CSI: Crime Scene Invesgaon” franchise. He’s sll at it, with a pilot in the works for CBS and “L.A.’s Finest,” a spinoff of “Bad Boys,” for Char‐ ter Communicaons’ new Spectrum Originals, set to air in May. “Jerry is in a league all of his own,” said Lloyd Greif, chief execuve officer of Los Angeles‐based investment bank Greif & Co. “He’s king of the acon film and he’s enjoyed similar success in television.” The TV business is changing, with a new breed of streaming services such as Nelix Inc. -

56 Billionaires in Texas See Net Worth Jump $24 Billion Or 10.1% in First Three Months of COVID-19 Pandemic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: July 1, 2020 56 Billionaires in Texas See Net Worth Jump $24 Billion or 10.1% in First Three Months of COVID-19 Pandemic Meanwhile State & Local Government Services Face Deep Cuts as Congress Stalls on New COVID-19 Financial Aid Package WASHINGTON—Texas has 56 billionaires who collectively saw their wealth increase by $24 billion or 10.1% during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic even as the state’s economy was reeling from a huge spike in joblessness and a collapse in taxes collected, a new report by Americans for Tax Fairness (ATF) and the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS). Three additional newly-minted billionaires joined the exclusive Texas club during the same period. Between March 18—the rough start date of the pandemic shutdown, when most federal and state economic restrictions were in place—and June 17, the total net worth of the state’s 56 billionaires rose from $238.9 billion to $276.3 billion, based on an analysis of Forbes data. Forbes’ annual billionaires report was published March 18, 2020, and the most recent real-time data was collected June 17 from the Forbes website. Fourteen Texas billionaires, including Michael Dell and Richard Kinder, saw their wealth grow by more than 25% during the pandemic period. Over roughly the same time, 2,400,000 of the state’s residents lost their jobs, 96,000 fell ill with the virus and 2,000 died from it. TEXAS BILLIONAIRES MARCH 18 TO JUNE 17, 2020 March 18 June 17 Real Wealth % Growth Net Worth Time Worth Growth in in 3 Primary Income Name (Millions) (Millions) 3 Months Months Source Industry Alice Walton $54,400 $53,307 -$1,093 -2.0% Walmart Fashion & Retail Michael Dell $22,900 $30,090 $7,190 31.4% Dell computers Technology Stanley Kroenke $10,000 $10,040 $40 0.4% sports, real estate Sports Jerry Jones $8,000 $8,060 $60 0.8% Dallas Cowboys Sports Andrew Beal $7,900 $8,798 $898 11.4% banks, real estate Finance & Investments Ann Walton Kroenke $7,900 $7,770 -$130 -1.6% Walmart Fashion & Retail Richard Kinder $5,200 $6,646 $1,446 27.8% pipelines Energy Robert F. -

The Regental Laureates Distinguished Presidential

REPORT TO CONTRIBUTORS Explore the highlights of this year’s report and learn more about how your generosity is making an impact on Washington and the world. CONTRIBUTOR LISTS (click to view) • The Regental Laureates • Henry Suzzallo Society • The Distinguished Presidential Laureates • The President’s Club • The Presidential Laureates • The President’s Club Young Leaders • The Laureates • The Benefactors THE REGENTAL LAUREATES INDIVIDUALS & ORGANIZATIONS / Lifetime giving totaling $100 million and above With their unparalleled philanthropic vision, our Regental Laureates propel the University of Washington forward — raising its profile, broadening its reach and advancing its mission around the world. Acknowledgement of the Regental Laureates can also be found on our donor wall in Suzzallo Library. Paul G. Allen & The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation Bill & Melinda Gates Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Microsoft DISTINGUISHED PRESIDENTIAL LAUREATES INDIVIDUALS & ORGANIZATIONS / Lifetime giving totaling $50 million to $99,999,999 Through groundbreaking contributions, our Distinguished Presidential Laureates profoundly alter the landscape of the University of Washington and the people it serves. Distinguished Presidential Laureates are listed in alphabetical order. Donors who have asked to be anonymous are not included in the listing. Acknowledgement of the Distinguished Presidential Laureates can also be found on our donor wall in Suzzallo Library. American Heart Association The Ballmer Group Boeing The Foster Foundation Jack MacDonald* Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Washington Research Foundation * = Deceased Bold Type Indicates donor reached giving level in fiscal year 2016–2017 1 THE PRESIDENTIAL LAUREATES INDIVIDUALS & ORGANIZATIONS / Lifetime giving totaling $10 million to $49,999,999 By matching dreams with support, Presidential Laureates further enrich the University of Washington’s top-ranked programs and elevate emerging disciplines to new heights. -

Lawyer Fall 2016

161882_Cover_TL-25coverfeature.qxp 9/15/16 8:12 PM Page CvrA TULANE UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL TULANE VOL.32–NO. 1 LAWYER FALL 2016 CHARMS CHALLENGES& ALUMNI IRRESISTIBLY PULLED BACK TO NEW ORLEANS ALSO INSIDE BLOGGING PROFESSORS LAW REVIEW CENTENNIAL DIVERSITY ENDOWMENT 161882_Cover_TL-25coverfeature.qxp 9/15/16 8:12 PM Page CvrB THE DOCKET 1 FRONT-PAGE FOOTNOTES 13 2 DEAN MEYER’S MEMO 3 BRIEFS 5 REAL-WORLD APPS Hands-on Learning 7 WORK PRODUCT Faculty Scholarship FOUR FIVE NEW PROFESSORSHIPS AWARDED. FACULTY TEST IDEAS THROUGH BLOGGING. SCHOLARLY WORK SPANS THE GLOBE. 13 CASE IN POINT CHARMS & CHALLENGES Alumni irresistibly pulled back to New Orleans 22 LAWFUL ASSEMBLY Events & Celebrations 27 RAISING THE BAR Donor Support NEW GRADS PROMOTE DIVERSITY. NEW SCHOLARSHIPS IN LITIGATION, BUSINESS, CIVIL LAW. GIFT ENHANCES CHINA INITIATIVES. 39 CLASS ACTIONS Alumni News & Reunions TULANE REMEMBERS JOHN GIFFEN WEINMANN. RIGHT: The 2016-17 LLMs and international students show their Tulane Law pride. Update your contact information at tulane.edu/alumni/update. Find us online: law.tulane.edu facebook.com/TulaneLawSchool Twitter: @TulaneLaw bit.ly/TulaneLawLinkedIn www.youtube.com/c/TulaneLaw FALL 2016 TULANE LAWYER VOL.32–NO.1 161882_01-2_TL-25coverfeature.qxp 9/15/16 7:19 PM Page 1 FRONT-PAGE FOOTNOTES CLASS PORTRAIT TULANE LAW SCHOOL CLASS OF 2019 198 students 100+ colleges/universities represented 34 U.S. jurisdictions represented THE CLASS OF 2019 INCLUDES: A speechwriter for a South American country’s mission at the United Nations age range 20–52 -

Speaker Biographies

SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Christopher T. Bavitz Christopher T. Bavitz is the WilmerHale Clinical Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, where he co-teaches the Counseling and Legal Strategy in the Digital Age seminar and teaches the seminar, Music & Digital Media. He is also Managing Director of HLS’s Cyberlaw Clinic, based at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society. And, he is a Faculty Co-Director of the Berkman Klein Center. Chris concentrates his practice on intellectual property and media law, particularly in the areas of music, entertainment, and technology. He oversees many of the Clinic’s projects relating to copyright, speech, advising of startups, and the use of technology to support access to justice, and he serves as the HLS Dean’s Designate to the Harvard Innovation Lab. Prior to joining the Clinic, Chris served as Senior Director of Legal Affairs for EMI Music North America. From 1998–2002, Chris was a litigation associate at Sonnenschein Nath & Rosenthal and RubinBaum LLP / Rubin Baum Levin Constant & Friedman, where he focused on copyright and trademark matters. Chris received his B.A., cum laude, from Tufts University in 1995 and his J.D. from University of Michigan Law School in 1998. Gabriella Blum, ’03 Gabriella Blum is the Rita E. Hauser Professor of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law at Harvard Law School, specializing in public international law, international negotiations, the law of armed conflict, and counterterrorism. She is also the Faculty Director of the Program on International Law and Armed Conflict (PILAC) and a member of the Program on Negotiation Executive Board. -

Cruise Ship Owners/Operators and Passenger Ship Financing & Management Companies

More than a Directory! Cruise Ship Owners/Operators and Passenger Ship Financing & Management Companies 1st Edition, April 2013 © 2013 by J. R. Kuehmayer www.amem.at Cruise Ship Owners / Operators Preface The AMEM Publication “Cruise Ship Owners/Operators and Passenger Ship Financing & Management Compa- nies” in fact is more than a directory! Company co-ordinates It is not only the most comprehensively and accurately structured listing of cruise ship owners and operators in the industry, despite the fact that the majority of cruise lines is more and more keeping both the company’s coordinates and the managerial staff secret. The entire industry is obtrusively focused on selling their services weeks and months ahead of the specific cruise date, collecting the money at a premature stage and staying almost unattainable for their clients pre and after cruise requests. They simply ignore the fact that there are suppliers and partners around who wish to keep in touch personally at least with the cruise line’s technical and procurement departments! The rest of the networking-information is camouflaged by the yellow-pages industry, which is facing a real prospect of extinction. The economic downturn is sending the already ailing business into a tailspin. The yellow-pages publishers basically give back in one downturn what took seven years to grow! Cruise Ship Financing It is more than a directory as it unveils the shift in the ship financing sector and uncovers how fast the traditional financiers to the cruise shipping industry fade away and perverted forms of financing are gaining ground. Admittedly there are some traditional banks around, which can maintain their market position through a blend of sober judgements, judicious risk management and solid relationships. -

Charles H. Baker Partner

Charles H. Baker Partner New York D: +1-212-326-2121 [email protected] Charles Baker is Co-Chair of O’Melveny’s Sports Industry Group. Admissions Chuck’s corporate practice encompasses mergers and acquisitions, private equity, and venture capital transactions, with Bar Admissions a core focus in the sports, media and consumer sectors. New York Chuck has represented buyers and sellers of sports franchises in the National Football League, National Basketball Association, Education National Hockey League, Major League Baseball, Major League Cornell University, J.D. Soccer, National Women’s Soccer League and many of the European football leagues. Recently, Chuck represented David Tepper, founder and president of global hedge fund Appaloosa Management, in his acquisition of the NFL’s Carolina Panthers and Charlotte FC, MLS’s 30th expansion team. Chuck has been featured by dozens of national publications and other media outlets as a thought leader in the fields of sports and entertainment law, and is also a frequent public speaker on those topics. Most recently, Law360 named Chuck to its 2020 list of Sports & Betting MVPs. The American Lawyer named Chuck to its prestigious 2019 “Dealmakers of the Year” list and he was also profiled in Variety’s 2018 and 2017 “Dealmakers Elite New York,” a feature spotlighting the most important players in the fields of law, finance, representation, and executive leadership. Chuck has been recognized nationally for sports law in the last six editions of Chambers USA: America’s Leading Lawyers for Business, which has described him as a “very strong practitioner” who is “well connected, incredibly bright and just able to get the deal closed” with “tremendous experience and know-how in the sports space.” O’Melveny & Myers LLP 1 He was also recognized by Law360 in 2015 and 2016 for his stellar M&A and sports law work, and by the Global M&A Network for his work on the sale of the Atlanta Hawks NBA team, naming it the “2015 USA Deal of the Year” at its prestigious M&A Atlas Awards. -

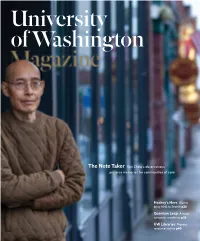

Hockey's Here Alumni Quantum Leap a Major UW Libraries Moving

The Note Taker Ron Chew’s observations preserve memories for communities of color Hockey’s Here Alumni bring NHL to Seattle p26 Quantum Leap A major computer revolution p34 UW Libraries Moving resources online p40 Rural Nursing Leticia Rodriguez, ’19, is one of those rare access to primary and preventive care, clinicians who choose to return to work they have shorter lives and are less likely in the rural community where they grew to survive a major health event like a heart up. The nurse practitioner moved her attack or stroke. In Washington, more than family back to Yakima two years ago when a million people—14% of the state’s pop- she joined the Children’s Village as a de- ulation—live in rural communities. velopmental-behavioral specialist. Some Because evidence shows that students of her patients come from very rural areas who train in rural settings are likely to of Central Washington where there are return to those or similar communities, no health-care providers. Premera Blue Cross has granted the UW Rodriguez sees a growing demand for $4.7 million to lead a program placing medical services in her community. So nursing students in rural practices through- does the UW. A National Rural Health out Washington. Through the Rural Association study found that residents in Nursing Health Initiative, 20 students rural areas face worse health outcomes each year over the next four years will find than their urban counterparts. With less clinical placements. Photo by Dennis Wise OF WASHINGTON WASHINGTON OF RURAL NURSING SPRING 2021 1 Trust.Whittier. -

Connecting Real Estate Investment Vehicles to Global Capital Sources US Real Estate Direct & Co- Investment Meeting West WEBINAR

Connecting Real Estate Investment Vehicles to Global Capital Sources US Real Estate Direct & Co- Investment Meeting West WEBINAR ZOOM WEBINAR Tuesday - March 17, 2020 US Real Estate Direct/Co-Investment Meeting West WEBINAR ZOOM WEBINAR– March 17, 2020 Dear Colleague, It is with great pleasure that I invite you to join The US Real Estate Direct & Co-Investment Meeting West WEBINAR. Originally, this was an in-person conference that was to be held at The Ritz-Carlton San Francisco on March 17th but due to the global health concern and the safety of our valued clients, we decided to turn this digital for now and will plan to have an in-person conference with the date to be announced shortly. We appreciate your support and flexibility during these difficult and uncertain times. The aim of this Webinar is to introduce direct investment and co-investment opportunities to Limited Partners that are actively looking to diversify their capital across all real estate related asset classes. Our WEBINAR brings together the most important real estate investment vehicles, institutional allocators and private wealth investors that are actively allocating in this space. Over 500 of the leading US based private equity real estate funds, institutional investors and other real estate and finance professionals will come together to learn and discuss investment opportunities, allocations, and the performance of all real estate related asset classes. We look forward to hosting you digitally! Best, Roy Carmo Salsinha President, CEO Carmo Companies By the Numbers… -

II Journals 2018 MEDIA KIT

www.iijournals.com II Journals 2018 MEDIA KIT ACCESS VOICE EXPOSURE The Voices of Influence John C. Bogle Mark Anson Cliff Asness The Vanguard Group Commonfund AQR Capital and Bogle Financial Management, LLC Markets Research Center “ In the very first issue ofThe Journal “ I have found the II Journals to provide “The Journal of Portfolio Management of Portfolio Management, way back high-quality research for both the is literally required reading for anyone in 1974, Paul Samuelson demanded academic and the practitioner. In particular, in the field of quantitative finance. If it ‘brute evidence’ that particular money I findThe Journal of Portfolio Management, had horoscopes and sports, I wouldn’t managers could beat the stock market The Journal of Private Equity, The Journal need any other periodicals.” on ‘a repeatable, sustainable basis.’ He of Alternative Investments, and The Journal found none. That article—‘Challenge to of Investing to be highly informative.” Judgment’—played a major role in my James P. Garland decision, less than a year later, to start CFA, the world’s first index mutual fund. Today The Jeffrey Company index funds constitute the lion’s share of Mike Sebastian some $3.2 trillion of assets entrusted to Aon Center for Vanguard by our shareholders. So, thank Innovation and Analytics “ Ignorance isn’t bliss. The Journal of you, Paul Samuelson; thank you, founding (ACIAÒ) in Singapore Portfolio Management is an invaluable tool editor Peter Bernstein; and thank you, for those serious practitioners who want Journal of Portfolio Management, which to understand investments. With rigorous “ I began my career in investments reading I continue to read—and to learn from— research plus practical advice, the JPM.