Hockey's Here Alumni Quantum Leap a Major UW Libraries Moving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE 20 Women Mayors of C40 Cities Reveal the Growing Power of the Women4Climate Movement The glass ceiling is being broken at the local level as all around the world, there are more women than ever before in city halls. Third Women4Climate Conference confirmed to take place at Paris City Hall on 20th February 2019 New York City, NY (14 June 2018) – Women leaders of the world’s greatest cities achieved a remarkable milestone today: with the election of London Breed as mayor of San Francisco, 20 of the world’s greatest cities are now led by women, representing 110 million urban citizens – greater than the population of Germany. The number of women mayors of C40’s leading global cities has increased five-fold in the last four years, rising from only 4 in early 2014. 21% of C40 mayors are now women and rising, confirming that the glass ceiling is being broken at the local level. Since becoming the first woman to Chair the C40 Cities network, Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo launched the Women4Climate Initiative that aims to empower by 2020, 500 young women taking bold climate action in the world’s leading cities. These climate heroines will be key in implementing Deadline 2020, the Paris Agreement roadmap for cities. Today C40 announced that the third annual Women4Climate Conference will take place at Paris City Hall on 20th February 2019. The Women4Climate conference, brings together inspiring women leaders from cities, business, investors, start-ups and the next generation of climate champions, to shape the climate future through innovative initiatives. -

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk Riya Kalra Junior Division Individual Exhibit Student-composed words: 499 Process paper: 500 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Black, Jason E., and Charles E. Morris, compilers. An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk's Speeches and Writings. University of California Press, 2013. This book is a compilation of Harvey Milk's speeches and interviews throughout his time in California. These interviews describe his views on the community and provide an idea as to what type of person he was. This book helped me because it gave me direct quotes from him and allowed me to clearly understand exactly what his perspective was on major issues. Board of Supervisors in January 8, 1978. City and County of San Francisco, sfbos.org/inauguration. Accessed 2 Jan. 2019. This image is of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from the time Harvey Milk was a supervisor. This image shows the people who were on the board with him. This helped my project because it gave a visual of many of the key people in the story of Harvey Milk. Braley, Colin E. Sharice Davids at a Victory Party. NBC, 6 Nov. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/sharice-davids-lesbian-native-american-makes- political-history-kansas-n933211. Accessed 2 May 2019. This is an image of Sharcie Davids at a victory party after she was elected to congress in Kansas. This image helped me because ti provided a face to go with he quote that I used on my impact section of board. California State, Legislature, Senate. Proposition 6. -

Reliability and Security of Large Scale Data Storage in Cloud Computing C.W

This article is part of the Reliability Society 2010 Annual Technical Report Reliability and Security of Large Scale Data Storage in Cloud Computing C.W. Hsu ¹¹¹ C.W. Wang ²²² Shiuhpyng Shieh ³³³ Department of Computer Science Taiwan Information Security Center at National Chiao Tung University NCTU (TWISC@NCTU) Email: ¹[email protected] ³[email protected] ²[email protected] Abstract In this article, we will present new challenges to the large scale cloud computing, namely reliability and security. Recent progress in the research area will be briefly reviewed. It has been proved that it is impossible to satisfy consistency, availability, and partitioned-tolerance simultaneously. Tradeoff becomes crucial among these factors to choose a suitable data access model for a distributed storage system. In this article, new security issues will be addressed and potential solutions will be discussed. Introduction “Cloud Computing ”, a novel computing model for large-scale application, has attracted much attention from both academic and industry. Since 2006, Google Inc. Chief Executive Eric Schmidt introduced the term into industry, and related research had been carried out in recent years. Cloud computing provides scalable deployment and fine-grained management of services through efficient resource sharing mechanism (most of them are for hardware resources, such as VM). Convinced by the manner called “ pay-as-you-go ” [1][2], companies can lower the cost of equipment management including machine purchasing, human maintenance, data backup, etc. Many cloud services rapidly appear on the Internet, such as Amazon’s EC2, Microsoft’s Azure, Google’s Gmail, Facebook, and so on. However, the well-known definition of the term “Cloud Computing ” was first given by Prof. -

Vader Couple's Arraignment Delayed Doctor's Office Steps Away From

$1 Weekend Edition Saturday, Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Dec. 6, 2014 Napavine Heartbreak Ski Season Underway Tigers Fall in Title Game / Sports 1 at White Pass / Main 5 Vader Couple’s Arraignment Delayed DELAYED: Brenda Wing Danny Wing, 26, and his ard L. Brosey continued the ar- it is “best” for him to continue the one who’s in jail, so you’re wife, Brenda Wing, 27, were raignment a week. his client’s arraignment as well. the one I’m concerned with,” Gets New Attorney; each scheduled to be arraigned “If Mr. Crowley is not here Before Pascoe stopped him Brosey said. Arraignment Will Take for the Oct. 5 death of Jasper at that time, I’m not inclined to from speaking, Danny Wing According to court docu- Henderling-Warner, who they continue a hearing … such as said his previously counsel was ments, the Wings’ timeline of Place Next Week had been caring for at the time. appointing an attorney to repre- “set up” by Brenda Wing’s family. events don’t quite match up — The both face a charge of sent your interests,” Brosey said. Danny Wing said he had no By Kaylee Osowski including when they picked up homicide by abuse, but their ar- Danny Wing has retained problem with the continuance Jasper to care for him. Both say [email protected] raignments were pushed back to representation with Vancouver- when asked by the judge if he they were only caring for him Dec. 11. Brenda Wing said since based defense attorney Todd was OK with the request. -

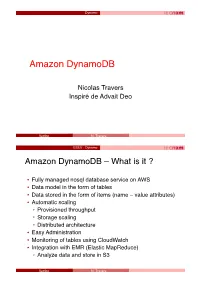

Amazon Dynamodb

Dynamo Amazon DynamoDB Nicolas Travers Inspiré de Advait Deo Vertigo N. Travers ESILV : Dynamo Amazon DynamoDB – What is it ? • Fully managed nosql database service on AWS • Data model in the form of tables • Data stored in the form of items (name – value attributes) • Automatic scaling ▫ Provisioned throughput ▫ Storage scaling ▫ Distributed architecture • Easy Administration • Monitoring of tables using CloudWatch • Integration with EMR (Elastic MapReduce) ▫ Analyze data and store in S3 Vertigo N. Travers ESILV : Dynamo Amazon DynamoDB – What is it ? key=value key=value key=value key=value Table Item (64KB max) Attributes • Primary key (mandatory for every table) ▫ Hash or Hash + Range • Data model in the form of tables • Data stored in the form of items (name – value attributes) • Secondary Indexes for improved performance ▫ Local secondary index ▫ Global secondary index • Scalar data type (number, string etc) or multi-valued data type (sets) Vertigo N. Travers ESILV : Dynamo DynamoDB Architecture • True distributed architecture • Data is spread across hundreds of servers called storage nodes • Hundreds of servers form a cluster in the form of a “ring” • Client application can connect using one of the two approaches ▫ Routing using a load balancer ▫ Client-library that reflects Dynamo’s partitioning scheme and can determine the storage host to connect • Advantage of load balancer – no need for dynamo specific code in client application • Advantage of client-library – saves 1 network hop to load balancer • Synchronous replication is not achievable for high availability and scalability requirement at amazon • DynamoDB is designed to be “always writable” storage solution • Allows multiple versions of data on multiple storage nodes • Conflict resolution happens while reads and NOT during writes ▫ Syntactic conflict resolution ▫ Symantec conflict resolution Vertigo N. -

SPOKANE CHIEFS Vs EVERETT SILVERTIPS A.O.T.W

WESTERN HOCKEY LEAGUE GAME NOTES / 2020-21 SPOKANE CHIEFS vs EVERETT SILVERTIPS A.O.T.W. Arena - Everett, WA. SATURDAY, MARCH 20, 2021 SPOKANE CHIEFS (0-0-0-1) 1 POINT EVERETT SILVERTIPS (0-0-0-0) 0 POINTS TEAM GAME: 2 ROAD GAME: 2 TEAM GAME: 1 HOME GAME: 1 HOME RECORD: 0-0-0-0 ROAD RECORD: 0-0-0-1 HOME RECORD: 0-0-0-0 ROAD RECORD: 0-0-0-0 SPECIAL TEAMS: PP: 8th 25.0 PK: 18th 66.7 SPECIAL TEAMS: PP: T-17 0.0 PK: T-1 100.0 GOALIES GOALIES # NAME YOB HT WT GP W L OTL SL SO GAA SV % # NAME YOB HT WT GP W L OTL SL SO GAA SV % 1 Campbell Arnold 02 6'0" 180 1 0 0 0 1 0 2.77 .919 31 Evan May 04 6'2" 163 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 30 Mason Beaupit 03 6'5" 184 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 32 Dustin Wolf 01 6'0" 168 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 31 Manny Panghil 04 6'2" 171 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 40 Braden Holt 03 6'1" 160 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 PLAYERS PLAYERS # POS NAME YOB HT WT GP G A PTS PIM +/- # POS NAME YOB HT WT GP G A PTS PIM +/- 2 D Logan Cunningham 04 6'1" 174 1 0 0 0 0 -1 3 D Brady Van Herk 03 6'4" 165 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 D Matt Leduc 00 6'5" 222 1 0 0 0 0 1 5 D Zach Ashton 01 6'0" 169 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 D Chase Friedt-Mohr 03 5'11" 179 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 D Ty Gibson 03 5'9" 192 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 D Jordan Chudley 01 6'3" 185 1 0 0 0 0 0 7 RW Ethan Regnier 00 5'10" 174 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 D Mac Gross 02 6'2" 187 1 0 0 0 2 1 8 D Ronan Seeley 02 6'1" 192 0 0 2 0 0 0 7 D Graham SWard 03 6'3" 177 1 0 0 0 2 1 9 C Ben Hemmerling 04 5'10" 144 0 0 2 0 0 0 11 LW Ty Cheveldayoff 03 6'#" 204 1 0 0 0 0 1 11 C Jacob Wright 02 5'10" 171 0 0 7 0 0 0 12 RW Erik Atchison 02 5'11" 181 1 1 0 1 2 -1 13 LW Brendan Lee 02 5'11" 194 -

One False Move for Years, Investing Legend DAVID BONDERMAN Could Do No Wrong. and Then He Tried to Buy a Utility from Enron. By

One False Move For years, investing legend DAVID BONDERMAN could do no wrong. And then he tried to buy a utility from Enron. By NICHOLAS VARCHAVER April 4, 2005 (FORTUNE Magazine) – THEY'RE THE KINGS of American business these days. Private equity firms, hedge funds, and their cash-laden ilk have been pulling the levers of capitalism, with investors you've never heard of amassing billions and buying corporate icons like Sears. Among this extremely quiet species, David Bonderman is as dominant as they come. He has earned a reputation as a master dealmaker, a tornado of a man spinning equal parts brilliance, energy, and charm inside his ever-moving vortex. His private equity partnership, Texas Pacific Group, has massive throw-weight. The firm says it has $20 billion under management--a gaudy sum that includes a series of under-the-radar Texas Pacific affiliates in the U.S. and Asia. That war chest puts the firm in the top tier of buyout funds and dwarfs those of raiders like Carl Icahn or even hedge fund upstarts like Eddie Lampert. Just in the U.S., Texas Pacific controls companies with annual revenues of $35 billion. If it were a public company, it would rank at No. 51 on the FORTUNE 500, somewhere between Motorola and Lockheed Martin. Like any private equity firm, Texas Pacific, which is based in Fort Worth and San Francisco, gathers cash from pension funds and wealthy investors and uses it to buy control of companies. What sets it apart from its peers is its reputation for taking on risky, unfixable companies--and then devoting serious resources to fixing them. -

American Leadership in Quantum Technology Joint Hearing

AMERICAN LEADERSHIP IN QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGY & SUBCOMMITTEE ON ENERGY COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, SPACE, AND TECHNOLOGY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 24, 2017 Serial No. 115–32 Printed for the use of the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://science.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 27–671PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, SPACE, AND TECHNOLOGY HON. LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas, Chair FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas DANA ROHRABACHER, California ZOE LOFGREN, California MO BROOKS, Alabama DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois SUZANNE BONAMICI, Oregon BILL POSEY, Florida ALAN GRAYSON, Florida THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky AMI BERA, California JIM BRIDENSTINE, Oklahoma ELIZABETH H. ESTY, Connecticut RANDY K. WEBER, Texas MARC A. VEASEY, Texas STEPHEN KNIGHT, California DONALD S. BEYER, JR., Virginia BRIAN BABIN, Texas JACKY ROSEN, Nevada BARBARA COMSTOCK, Virginia JERRY MCNERNEY, California BARRY LOUDERMILK, Georgia ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado RALPH LEE ABRAHAM, Louisiana PAUL TONKO, New York DRAIN LAHOOD, Illinois BILL FOSTER, Illinois DANIEL WEBSTER, Florida MARK TAKANO, California JIM BANKS, Indiana COLLEEN HANABUSA, Hawaii ANDY BIGGS, Arizona CHARLIE CRIST, Florida ROGER W. MARSHALL, Kansas NEAL P. DUNN, Florida CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana RALPH NORMAN, South Carolina SUBCOMMITTEE ON RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGY HON. BARBARA COMSTOCK, Virginia, Chair FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois ELIZABETH H. -

Sports Arena Site for New Pop-Up Donor Center in Everett

For Immediate Release Date: 11 May 2020 Contact: John Yeager | 425-765-9845 | [email protected] Karen Kirby | 206-689-6359| [email protected] Sports Arena Site For New Pop-Up Donor Center in Everett Seattle Storm and Everett Silvertips Transform Angel Of The Winds Arena into Pop-Up Donor Center to Support Bloodworks Northwest and Everett Community. Everett, WA — Bloodworks Northwest is joined by the Seattle Storm and Everett Silvertips in the effort to ensure a safe and reliable community blood supply amid the COVID-19 pandemic. From May 14 – June 6, 2020, the Edward D. Hansen Conference Center at Angel Of The Winds Arena will be transformed into a Pop-Up Donor Center experience and a lifeline for local patients. Storm and Silvertip fans are urged to make their one-hour donation appointment today as a safe and essential action to support local patients. In accordance with current social distancing guidelines, only scheduled appointments will be allowed. No walk-ins, guests, or people under age 16 are permitted onsite. On the day of their appointment, fans are invited to wear team colors and spread the word with #WeGotThis. Every donor will receive a pair of tickets to an upcoming Storm and Silvertips game. Social distancing recommendations have put a strain on opportunities to donate, as traditional blood drives and bloodmobiles are temporarily unavailable. Bloodworks has turned to an innovative alternative with Pop-Up Donor Centers that are held in large venues, allowing higher level of space and safety for donors and staff. “We’re grateful to have Angel Of The Winds Arena opening its doors to Seattle Storm and Everett Silvertips fans and Snohomish County neighbors to ensure the local blood supply is ready to respond to the increased need for blood as hospitals prepare to resume elective surgeries,” said Bloodworks Northwest President & CEO Curt Bailey. -

Leading in a Complex World

LEADING IN A COMPLEX WORLD CHANCELLOR WILLIAM H. MCRAVEN’S VISION AND FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM PRESENTED TO THE BOARD OF REGENTS, NOVEMBER 2015 BOARD OF REGENTS Paul L. Foster, Chairman R. Steven Hicks, Vice Chairman Jeffery D. Hildebrand, Vice Chairman Regent Ernest Aliseda Regent David J. Beck Regent Alex M. Cranberg Regent Wallace L. Hall, Jr. Regent Brenda Pejovich Regent Sara Martinez Tucker Student Regent Justin A. Drake GENERAL COUNSEL TO THE BOARD OF REGENTS Francie A. Frederick As of November 2015 Chancellor’s Vision TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 Letter from Chairman Paul L. Foster 04 Letter from Chancellor William H. McRaven 05 Introduction 07 UT System’s Mission Statement 09 Operating Concept 11 Agile Decision Process 13 Strategic Assessment 17 Framework for Advancing Excellence 19 Team of Teams 23 Quantum Leap: The Texas Prospect Initiative 25 Quantum Leap: The American Leadership Program 27 Quantum Leap: Win the Talent War 29 Quantum Leap: Enhancing Fairness & Opportunity 31 Quantum Leap: The UT Health Care Enterprise 33 Quantum Leap: Leading the Brain Health Revolution 35 Quantum Leap: The UT Network for National Security 37 Quantum Leap: UT System Expansion in Houston 39 Conclusion & Ethos Office of the BOARD OF REGENTS During my time as a UT System Regent, and most recently as chairman of the board, I have witnessed many great moments in the history of our individual institutions and significant, game-changing events for our system as a whole. No single event has left me more optimistic about the future of The University of Texas System than Chancellor William H. -

Wednesday, August 25 – 12:30 PM

Spokane Public Facilities District - Board of Director’s Meeting Tuesday, September 21 – 11am Board of Directors -Spokane Public Facilities District TENTATIVE AGENDA – Tuesday, September 21 2021 – 11:00a.m. Regular Board Meeting via Webinar https://attendee.gotowebinar.com/register/112549726501332235 SPFD Board Documents at www.spokanepfd.org Call to Order the 810th Meeting of the Spokane Public Facilities District 1. Consent Agenda A. Approval of Minutes – September 8, 2021 B. Approval of Expenditures for August 2021 C. Approval of Witherspoon-Kelley Invoices for August 2021 D. Approval of Division Axiom 7 Change Orders (1-3) – Arena Roof 2. District Business A. Committees 1. Finance i. Financials for August 2021 2. Operations 3. Project i. The Podium a. Lydig Pay App #35 for August 2021 b. Project Update 3. Miscellaneous A. CEO Update 4. Public Comments Anyone wishing to speak before the Board, either as an individual or as a member of a group may do so at this time. Individuals desiring to speak shall give their name, and the group they represent, if any. A speaker is limited to three minutes unless granted an extension of time. The Board will take action only on agenda items, not on general comments. 5. Adjournment Upcoming SPFD Board Meetings In-person and/or via Webinar: Wednesday, September 22 at 12:30 pm – (via Webinar) Wednesday, October 13 at 12:30 pm – (via Webinar) Wednesday, October 27 at 12:30 pm – (via Webinar) District Vision ~ To create event experiences that make our guests say WOW! Spokane Convention Center Spokane Veterans -

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners TACOMA RAINIERS BASEBALL tacomarainiers.com CHENEY STADIUM /TacomaRainiers 2502 S. Tyler Street Tacoma, WA 98405 @RainiersLand Phone: 253.752.7707 tacomarainiers Fax: 253.752.7135 2019 TACOMA RAINIERS MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Front Office/Contact Info .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Cheney Stadium .....................................................................................................................................................6-9 Coaching Staff ....................................................................................................................................................10-14 2019 Tacoma Rainiers Players ...........................................................................................................................15-76 2018 Season Review ........................................................................................................................................77-106 League Leaders and Final Standings .........................................................................................................78-79 Team Batting/Pitching/Fielding Summary ..................................................................................................80-81 Monthly Batting/Pitching Totals ..................................................................................................................82-85 Situational