Computational Caches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

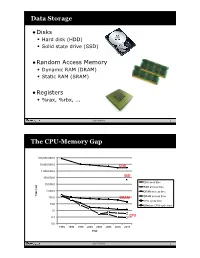

Data Storage the CPU-Memory

Data Storage •Disks • Hard disk (HDD) • Solid state drive (SSD) •Random Access Memory • Dynamic RAM (DRAM) • Static RAM (SRAM) •Registers • %rax, %rbx, ... Sean Barker 1 The CPU-Memory Gap 100,000,000.0 10,000,000.0 Disk 1,000,000.0 100,000.0 SSD Disk seek time 10,000.0 SSD access time 1,000.0 DRAM access time Time (ns) Time 100.0 DRAM SRAM access time CPU cycle time 10.0 Effective CPU cycle time 1.0 0.1 CPU 0.0 1985 1990 1995 2000 2003 2005 2010 2015 Year Sean Barker 2 Caching Smaller, faster, more expensive Cache 8 4 9 10 14 3 memory caches a subset of the blocks Data is copied in block-sized 10 4 transfer units Larger, slower, cheaper memory Memory 0 1 2 3 viewed as par@@oned into “blocks” 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 3 Cache Hit Request: 14 Cache 8 9 14 3 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 4 Cache Miss Request: 12 Cache 8 12 9 14 3 12 Request: 12 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 5 Locality ¢ Temporal locality: ¢ Spa0al locality: Sean Barker 6 Locality Example (1) sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < n; i++) sum += a[i]; return sum; Sean Barker 7 Locality Example (2) int sum_array_rows(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < M; i++) for (j = 0; j < N; j++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 8 Locality Example (3) int sum_array_cols(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (j = 0; j < N; j++) for (i = 0; i < M; i++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 9 The Memory Hierarchy The Memory Hierarchy Smaller On 1 cycle to access CPU Chip Registers Faster Storage Costlier instrs can L1, L2 per byte directly Cache(s) ~10’s of cycles to access access (SRAM) Main memory ~100 cycles to access (DRAM) Larger Slower Flash SSD / Local network ~100 M cycles to access Cheaper Local secondary storage (disk) per byte slower Remote secondary storage than local (tapes, Web servers / Internet) disk to access Sean Barker 10. -

CS 2210: Theory of Computation

CS 2210: Theory of Computation Spring, 2019 Administrative Information • Background survey • Textbook: E. Rich, Automata, Computability, and Complexity: Theory and Applications, Prentice-Hall, 2008. • Book website: http://www.cs.utexas.edu/~ear/cs341/automatabook/ • My Office Hours: – Monday, 6:00-8:00pm, Searles 224 – Tuesday, 1:00-2:30pm, Searles 222 • TAs – Anjulee Bhalla: Hours TBA, Searles 224 – Ryan St. Pierre, Hours TBA, Searles 224 What you can expect from the course • How to do proofs • Models of computation • What’s the difference between computability and complexity? • What’s the Halting Problem? • What are P and NP? • Why do we care whether P = NP? • What are NP-complete problems? • Where does this make a difference outside of this class? • How to work the answers to these questions into the conversation at a cocktail party… What I will expect from you • Problem Sets (25%): – Goal: Problems given on Mondays and Wednesdays – Due the next Monday – Graded by following Monday – A learning tool, not a testing tool – Collaboration encouraged; more on this in next slide • Quizzes (15%) • Exams (2 non-cumulative, 30% each): – Closed book, closed notes, but… – Can bring in 8.5 x 11 page with notes on both sides • Class participation: Tiebreaker Other Important Things • Go to the TA hours • Study and work on problem sets in groups • Collaboration Issues: – Level 0 (In-Class Problems) • No restrictions – Level 1 (Homework Problems) • Verbal collaboration • But, individual write-ups – Level 2 (not used in this course) • Discussion with TAs only – Level 3 (Exams) • Professor clarifications only Right now… • What does it mean to study the “theory” of something? • Experience with theory in other disciplines? • Relationship to practice? – “In theory, theory and practice are the same. -

The Problem with Threads

The Problem with Threads Edward A. Lee Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California at Berkeley Technical Report No. UCB/EECS-2006-1 http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2006/EECS-2006-1.html January 10, 2006 Copyright © 2006, by the author(s). All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission. Acknowledgement This work was supported in part by the Center for Hybrid and Embedded Software Systems (CHESS) at UC Berkeley, which receives support from the National Science Foundation (NSF award No. CCR-0225610), the State of California Micro Program, and the following companies: Agilent, DGIST, General Motors, Hewlett Packard, Infineon, Microsoft, and Toyota. The Problem with Threads Edward A. Lee Professor, Chair of EE, Associate Chair of EECS EECS Department University of California at Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720, U.S.A. [email protected] January 10, 2006 Abstract Threads are a seemingly straightforward adaptation of the dominant sequential model of computation to concurrent systems. Languages require little or no syntactic changes to sup- port threads, and operating systems and architectures have evolved to efficiently support them. Many technologists are pushing for increased use of multithreading in software in order to take advantage of the predicted increases in parallelism in computer architectures. -

Computer Architecture: Dataflow (Part I)

Computer Architecture: Dataflow (Part I) Prof. Onur Mutlu Carnegie Mellon University A Note on This Lecture n These slides are from 18-742 Fall 2012, Parallel Computer Architecture, Lecture 22: Dataflow I n Video: n http://www.youtube.com/watch? v=D2uue7izU2c&list=PL5PHm2jkkXmh4cDkC3s1VBB7- njlgiG5d&index=19 2 Some Required Dataflow Readings n Dataflow at the ISA level q Dennis and Misunas, “A Preliminary Architecture for a Basic Data Flow Processor,” ISCA 1974. q Arvind and Nikhil, “Executing a Program on the MIT Tagged- Token Dataflow Architecture,” IEEE TC 1990. n Restricted Dataflow q Patt et al., “HPS, a new microarchitecture: rationale and introduction,” MICRO 1985. q Patt et al., “Critical issues regarding HPS, a high performance microarchitecture,” MICRO 1985. 3 Other Related Recommended Readings n Dataflow n Gurd et al., “The Manchester prototype dataflow computer,” CACM 1985. n Lee and Hurson, “Dataflow Architectures and Multithreading,” IEEE Computer 1994. n Restricted Dataflow q Sankaralingam et al., “Exploiting ILP, TLP and DLP with the Polymorphous TRIPS Architecture,” ISCA 2003. q Burger et al., “Scaling to the End of Silicon with EDGE Architectures,” IEEE Computer 2004. 4 Today n Start Dataflow 5 Data Flow Readings: Data Flow (I) n Dennis and Misunas, “A Preliminary Architecture for a Basic Data Flow Processor,” ISCA 1974. n Treleaven et al., “Data-Driven and Demand-Driven Computer Architecture,” ACM Computing Surveys 1982. n Veen, “Dataflow Machine Architecture,” ACM Computing Surveys 1986. n Gurd et al., “The Manchester prototype dataflow computer,” CACM 1985. n Arvind and Nikhil, “Executing a Program on the MIT Tagged-Token Dataflow Architecture,” IEEE TC 1990. -

Ece585 Lec2.Pdf

ECE 485/585 Microprocessor System Design Lecture 2: Memory Addressing 8086 Basics and Bus Timing Asynchronous I/O Signaling Zeshan Chishti Electrical and Computer Engineering Dept Maseeh College of Engineering and Computer Science Source: Lecture based on materials provided by Mark F. Basic I/O – Part I ECE 485/585 Outline for next few lectures Simple model of computation Memory Addressing (Alignment, Byte Order) 8088/8086 Bus Asynchronous I/O Signaling Review of Basic I/O How is I/O performed Dedicated/Isolated /Direct I/O Ports Memory Mapped I/O How do we tell when I/O device is ready or command complete? Polling Interrupts How do we transfer data? Programmed I/O DMA ECE 485/585 Simplified Model of a Computer Control Control Data, Address, Memory Data Path Microprocessor Keyboard Mouse [Fetch] Video display [Decode] Printer [Execute] I/O Device Hard disk drive Audio card Ethernet WiFi CD R/W DVD ECE 485/585 Memory Addressing Size of operands Bytes, words, long/double words, quadwords 16-bit half word (Intel: word) 32-bit word (Intel: doubleword, dword) 0x107 64-bit double word (Intel: quadword, qword) 0x106 Note: names are non-standard 0x105 SUN Sparc word is 32-bits, double is 64-bits 0x104 0x103 Alignment 0x102 Can multi-byte operands begin at any byte address? 0x101 Yes: non-aligned 0x100 No: aligned. Low order address bit(s) will be zero ECE 485/585 Memory Operand Alignment …Intel IA speak (i.e. word = 16-bits = 2 bytes) 0x107 0x106 0x105 0x104 0x103 0x102 0x101 0x100 Aligned Unaligned Aligned Unaligned Aligned Unaligned word word Double Double Quad Quad address address word word word word -----0 address address address address -----00 ----000 ECE 485/585 Memory Operand Alignment Why do we care? Unaligned memory references Can cause multiple memory bus cycles for a single operand May also span cache lines Requiring multiple evictions, multiple cache line fills Complicates memory system and cache controller design Some architectures restrict addresses to be aligned Even in architectures without alignment restrictions (e.g. -

Cache-Aware Roofline Model: Upgrading the Loft

1 Cache-aware Roofline model: Upgrading the loft Aleksandar Ilic, Frederico Pratas, and Leonel Sousa INESC-ID/IST, Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal ilic,fcpp,las @inesc-id.pt f g Abstract—The Roofline model graphically represents the attainable upper bound performance of a computer architecture. This paper analyzes the original Roofline model and proposes a novel approach to provide a more insightful performance modeling of modern architectures by introducing cache-awareness, thus significantly improving the guidelines for application optimization. The proposed model was experimentally verified for different architectures by taking advantage of built-in hardware counters with a curve fitness above 90%. Index Terms—Multicore computer architectures, Performance modeling, Application optimization F 1 INTRODUCTION in Tab. 1. The horizontal part of the Roofline model cor- Driven by the increasing complexity of modern applica- responds to the compute bound region where the Fp can tions, microprocessors provide a huge diversity of compu- be achieved. The slanted part of the model represents the tational characteristics and capabilities. While this diversity memory bound region where the performance is limited is important to fulfill the existing computational needs, it by BD. The ridge point, where the two lines meet, marks imposes challenges to fully exploit architectures’ potential. the minimum I required to achieve Fp. In general, the A model that provides insights into the system performance original Roofline modeling concept [10] ties the Fp and the capabilities is a valuable tool to assist in the development theoretical bandwidth of a single memory level, with the I and optimization of applications and future architectures. -

ARM-Architecture Simulator Archulator

Embedded ECE Lab Arm Architecture Simulator University of Arizona ARM-Architecture Simulator Archulator Contents Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Description ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Block Diagram ............................................................................................................................ 2 Component Description .............................................................................................................. 3 Buses ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 µP .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Caches ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Memory ................................................................................................................................................. 3 CoProcessor .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Using the Archulator ...................................................................................................................... -

Multi-Tier Caching Technology™

Multi-Tier Caching Technology™ Technology Paper Authored by: How Layering an Application’s Cache Improves Performance Modern data storage needs go far beyond just computing. From creative professional environments to desktop systems, Seagate provides solutions for almost any application that requires large volumes of storage. As a leader in NAND, hybrid, SMR and conventional magnetic recording technologies, Seagate® applies different levels of caching and media optimization to benefit performance and capacity. Multi-Tier Caching (MTC) Technology brings the highest performance and areal density to a multitude of applications. Each Seagate product is uniquely tailored to meet the performance requirements of a specific use case with the right memory, NAND, and media type and size. This paper explains how MTC Technology works to optimize hard drive performance. MTC Technology: Key Advantages Capacity requirements can vary greatly from business to business. While the fastest performance can be achieved using Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) cache, the data in the DRAM is not persistent through power cycles and DRAM is very expensive compared to other media. NAND flash data survives through power cycles but it is still very expensive compared to a magnetic storage medium. Magnetic storage media cache offers good performance at a very low cost. On the downside, media cache takes away overall disk drive capacity from PMR or SMR main store media. MTC Technology solves this dilemma by using these diverse media components in combination to offer different levels of performance and capacity at varying price points. By carefully tuning firmware with appropriate cache types and sizes, the end user can experience excellent overall system performance. -

CUDA 11 and A100 - WHAT’S NEW? Markus Hrywniak, 23Rd June 2020 TOPICS for TODAY

CUDA 11 AND A100 - WHAT’S NEW? Markus Hrywniak, 23rd June 2020 TOPICS FOR TODAY Ampere architecture – A100, powering DGX–A100, HGX-A100... and soon, FZ Jülich‘s JUWELS Booster New CUDA 11 Toolkit release Overview of features Talk next week: Third generation Tensor Cores GTC talks go into much more details. See references! 2 HGX-A100 4-GPU HGX-A100 8-GPU • 4 A100 with NVLINK • 8 A100 with NVSwitch 3 HIERARCHY OF SCALES Multi-System Rack Multi-GPU System Multi-SM GPU Multi-Core SM Unlimited Scale 8 GPUs 108 Multiprocessors 2048 threads 4 AMDAHL’S LAW serial section parallel section serial section Amdahl’s Law parallel section Shortest possible runtime is sum of serial section times Time saved serial section Some Parallelism Increased Parallelism Infinite Parallelism Program time = Parallel sections take less time Parallel sections take no time sum(serial times + parallel times) Serial sections take same time Serial sections take same time 5 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY serial section parallel section serial section Split up serial & parallel components parallel section serial section Some Parallelism Task Parallelism Infinite Parallelism Program time = Parallel sections overlap with serial sections Parallel sections take no time sum(serial times + parallel times) Serial sections take same time 6 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY CUDA Concurrency Mechanisms At Every Scope CUDA Kernel Threads, Warps, Blocks, Barriers Application CUDA Streams, CUDA Graphs Node Multi-Process Service, GPU-Direct System NCCL, CUDA-Aware MPI, NVSHMEM 7 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY Execution Overheads Non-productive latencies (waste) Operation Latency Network latencies Memory read/write File I/O .. -

10. Assembly Language, Models of Computation

10. Assembly Language, Models of Computation 6.004x Computation Structures Part 2 – Computer Architecture Copyright © 2015 MIT EECS 6.004 Computation Structures L10: Assembly Language, Models of Computation, Slide #1 Beta ISA Summary • Storage: – Processor: 32 registers (r31 hardwired to 0) and PC – Main memory: Up to 4 GB, 32-bit words, 32-bit byte addresses, 4-byte-aligned accesses OPCODE rc ra rb unused • Instruction formats: OPCODE rc ra 16-bit signed constant 32 bits • Instruction classes: – ALU: Two input registers, or register and constant – Loads and stores: access memory – Branches, Jumps: change program counter 6.004 Computation Structures L10: Assembly Language, Models of Computation, Slide #2 Programming Languages 32-bit (4-byte) ADD instruction: 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 opcode rc ra rb (unused) Means, to the BETA, Reg[4] ß Reg[2] + Reg[3] We’d rather write in assembly language: Today ADD(R2, R3, R4) or better yet a high-level language: Coming up a = b + c; 6.004 Computation Structures L10: Assembly Language, Models of Computation, Slide #3 Assembly Language Symbolic 01101101 11000110 Array of bytes representation Assembler 00101111 to be loaded of stream of bytes 10110001 into memory ..... Source Binary text file machine language • Abstracts bit-level representation of instructions and addresses • We’ll learn UASM (“microassembler”), built into BSim • Main elements: – Values – Symbols – Labels (symbols for addresses) – Macros 6.004 Computation Structures L10: Assembly Language, Models -

Actor Model of Computation

Published in ArXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/1008.1459 Actor Model of Computation Carl Hewitt http://carlhewitt.info This paper is dedicated to Alonzo Church and Dana Scott. The Actor model is a mathematical theory that treats “Actors” as the universal primitives of concurrent digital computation. The model has been used both as a framework for a theoretical understanding of concurrency, and as the theoretical basis for several practical implementations of concurrent systems. Unlike previous models of computation, the Actor model was inspired by physical laws. It was also influenced by the programming languages Lisp, Simula 67 and Smalltalk-72, as well as ideas for Petri Nets, capability-based systems and packet switching. The advent of massive concurrency through client- cloud computing and many-core computer architectures has galvanized interest in the Actor model. An Actor is a computational entity that, in response to a message it receives, can concurrently: send a finite number of messages to other Actors; create a finite number of new Actors; designate the behavior to be used for the next message it receives. There is no assumed order to the above actions and they could be carried out concurrently. In addition two messages sent concurrently can arrive in either order. Decoupling the sender from communications sent was a fundamental advance of the Actor model enabling asynchronous communication and control structures as patterns of passing messages. November 7, 2010 Page 1 of 25 Contents Introduction ............................................................ 3 Fundamental concepts ............................................ 3 Illustrations ............................................................ 3 Modularity thru Direct communication and asynchrony ............................................................. 3 Indeterminacy and Quasi-commutativity ............... 4 Locality and Security ............................................ -

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 L/780

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 l/780 Joel S. Emer Douglas W. Clark Digital Equipment Corp. Digital Equipment Corp. 77 Reed Road 295 Foster Street Hudson, MA 01749 Littleton, MA 01460 ABSTRACT effect of many architectural and implementation features. This paper reports the results of a study of VAX- llR80 processor performance using a novel hardware Prior related work includes studies of opcode monitoring technique. A micro-PC histogram frequency and other features of instruction- monitor was buiit for these measurements. It kee s a processing [lo. 11,15,161; some studies report timing count of the number of microcode cycles execute z( at Information as well [l, 4,121. each microcode location. Measurement ex eriments were performed on live timesharing wor i loads as After describing our methods and workloads in well as on synthetic workloads of several types. The Section 2, we will re ort the frequencies of various histogram counts allow the calculation of the processor events in 5 ections 3 and 4. Section 5 frequency of various architectural events, such as the resents the complete, detailed timing results, and frequency of different types of opcodes and operand !!Iection 6 concludes the paper. specifiers, as well as the frequency of some im lementation-s ecific events, such as translation bu h er misses. ?phe measurement technique also yields the amount of processing time spent, in various 2. DEFINITIONS AND METHODS activities, such as ordinary microcode computation, memory management, and processor stalls of 2.1 VAX-l l/780 Structure different kinds. This paper reports in detail the amount of time the “average’ VAX instruction The llf780 processor is composed of two major spends in these activities.