Global Engagement in Science: the University’S Fourth Mission?” Science & Diplomacy, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Pure Appl. Chem. 2016; 88(10-11): 917–918 Editorial Hugh D. Burrows* and Richard M. Hartshorn* The 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry DOI 10.1515/pac-2016-2005 Keywords: Ben L. Feringa; Jean-Pierre Sauvage; J. Fraser Stoddart; Nobel Prize in Chemistry; 2016. Pure and Applied Chemistry warmly congratulates Jean-Pierre Sauvage (University of Strasbourg, France), Sir J. Fraser Stoddart (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA), and Bernard (Ben) L. Feringa (Univer- sity of Groningen, the Netherlands) on their award of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The citation from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences states that the award is “for the design and synthesis of molecu- lar machines”. Their work encompasses a broad spectrum of Chemistry, from elegant synthetic studies of catenanes, rotaxanes and other formerly considered exotic molecules, through coordination chemistry, and electron transfer reactions, to molecular switches and rotors driven by light and other external sources. They have all participated actively in IUPAC endorsed meetings and conference series, including the IUPAC World Congress in Chemistry, IUPAC International Conferences on Organic Synthesis (ICOS), Physical Organic Chemistry (ICPOC), and Coordination Chemistry (ICCC), and IUPAC International Symposia on Macrocyclic Chemistry (ISMC), Organometallic Chemistry Directed Towards Organic Synthesis (OMCOS), Novel Aromatic Compounds (ISNA), Carbohydrate Chemistry (ICS), the Chemistry of Natural Products ISCNP), and Photo- chemistry. Pure Appl. Chem. publishes collections of papers based upon authoritative lectures presented at such IUPAC endorsed events, in addition to IUPAC Recommendations, and Technical Reports. We are very pleased to highlight the following publications from these three Nobel Laureates that have been published in Pure and Applied Chemistry as a result of their involvement in these conferences. -

Chemical Synthesis

www.iupac2017.org Adriano D. Andricopulo Chairman of the IUPAC-2017 Organizing Committee Brazil: Key Figures and Facts • Brazil is Latin America's largest country (47% of the South America Continent) and the fifth largest country in the world • Population: 204 million people (the fifth most populous in the world ) • Language: Portuguese . Official currency: Brazilian Real (1.00 USD = R$ 3.12) • Brazil has the world’s ninth-largest economy and the largest in Latin America Brazil: Key Figures and Facts . São Paulo has the largest population, industrial complex, and economic production in Brazil . Population: 12 million people (45 million in SP state) . It is the largest city in South America, and the fifth largest in the world . São Paulo State is responsible for 40% of the Brazilian GDP . Climate: humid subtropical, temperatures in July: 12 and 22°C (54°F and 72°F) . Number of tourists in 2016: > 18 million WTC Events Center and Sheraton WTC Hotel are the most complete complex for events in Latin America Approximately 12,000 m² are available and divided into 60 flexible spaces Services: Parking Restaurants Banks Currency exchange Travel agency Pharmacies Hairdresser’s Stationery General Aspects - 9 Plenary Lectures, including 4 Noble Laureates - About 120 Sessions in 12 major themes - Several Keynote, Invited, Oral and Young Scientists Opening Ceremony Special Symposia Welcome Reception 3 Poster Sessions Half-day Social Program Gala Dinner Exhibition Plenary Lectures Sir J. Fraser Stoddart (Nobel Prize 2016) Department of Chemistry -

Nobel Laureates Endorse Joe Biden

Nobel Laureates endorse Joe Biden 81 American Nobel Laureates in Physics, Chemistry, and Medicine have signed this letter to express their support for former Vice President Joe Biden in the 2020 election for President of the United States. At no time in our nation’s history has there been a greater need for our leaders to appreciate the value of science in formulating public policy. During his long record of public service, Joe Biden has consistently demonstrated his willingness to listen to experts, his understanding of the value of international collaboration in research, and his respect for the contribution that immigrants make to the intellectual life of our country. As American citizens and as scientists, we wholeheartedly endorse Joe Biden for President. Name Category Prize Year Peter Agre Chemistry 2003 Sidney Altman Chemistry 1989 Frances H. Arnold Chemistry 2018 Paul Berg Chemistry 1980 Thomas R. Cech Chemistry 1989 Martin Chalfie Chemistry 2008 Elias James Corey Chemistry 1990 Joachim Frank Chemistry 2017 Walter Gilbert Chemistry 1980 John B. Goodenough Chemistry 2019 Alan Heeger Chemistry 2000 Dudley R. Herschbach Chemistry 1986 Roald Hoffmann Chemistry 1981 Brian K. Kobilka Chemistry 2012 Roger D. Kornberg Chemistry 2006 Robert J. Lefkowitz Chemistry 2012 Roderick MacKinnon Chemistry 2003 Paul L. Modrich Chemistry 2015 William E. Moerner Chemistry 2014 Mario J. Molina Chemistry 1995 Richard R. Schrock Chemistry 2005 K. Barry Sharpless Chemistry 2001 Sir James Fraser Stoddart Chemistry 2016 M. Stanley Whittingham Chemistry 2019 James P. Allison Medicine 2018 Richard Axel Medicine 2004 David Baltimore Medicine 1975 J. Michael Bishop Medicine 1989 Elizabeth H. Blackburn Medicine 2009 Michael S. -

Molecular Machines Series: Topics in Current Chemistry

springer.com T. Ross Kelly (Ed.) Molecular Machines Series: Topics in Current Chemistry This series presents critical reviews of the present position and future trends in modern chemical research. Short and concise reports on chemistry, each written by the world renowned experts. Still valid and useful after 5 or 10 years. More information as well as the electronic version of the whole content available at: springerlink.com The chapters in this volume describe bottom-up strategies and chronicle cutting-edge advances from several of the world’s leading laboratories engaged in the development of molecular machines. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2016 was awarded jointly to Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart and Bernard L. Feringa"for the design and synthesis of molecular machines". Both Jean-Pierre Sauvage and Sir J. Fraser Stoddart have also contributed to this book. XII, 236 p. Printed book Hardcover 179,95 € | £142.50 | $269.00 [1]192,55 € (D) | 197,95 € (A) | CHF 299,29 eBook 149,99 € | £114.00 | $209.00 [2]149,99 € (D) | 149,99 € (A) | CHF 239,00 Available from your library or springer.com/shop MyCopy [3] Printed eBook for just € | $ 24.99 springer.com/mycopy Order online at springer.com / or for the Americas call (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER / or email us at: [email protected]. / For outside the Americas call +49 (0) 6221-345-4301 / or email us at: [email protected]. The first € price and the £ and $ price are net prices, subject to local VAT. Prices indicated with [1] include VAT for books; the €(D) includes 7% for Germany, the €(A) includes 10% for Austria. -

The Grand Challenges in the Chemical Sciences

The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities Celebrating the 70 th birthday of the State of Israel conference on THE GRAND CHALLENGES IN THE CHEMICAL SCIENCES Jerusalem, June 3-7 2018 Biographies and Abstracts The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities Celebrating the 70 th birthday of the State of Israel conference on THE GRAND CHALLENGES IN THE CHEMICAL SCIENCES Participants: Jacob Klein Dan Shechtman Dorit Aharonov Roger Kornberg Yaron Silberberg Takuzo Aida Ferenc Krausz Gabor A. Somorjai Yitzhak Apeloig Leeor Kronik Amiel Sternberg Frances Arnold Richard A. Lerner Sir Fraser Stoddart Ruth Arnon Raphael D. Levine Albert Stolow Avinoam Ben-Shaul Rudolph A. Marcus Zehev Tadmor Paul Brumer Todd Martínez Reshef Tenne Wah Chiu Raphael Mechoulam Mark H. Thiemens Nili Cohen David Milstein Naftali Tishby Nir Davidson Shaul Mukamel Knut Wolf Urban Ronnie Ellenblum Edvardas Narevicius Arieh Warshel Greg Engel Nathan Nelson Ira A. Weinstock Makoto Fujita Hagai Netzer Paul Weiss Oleg Gang Abraham Nitzan Shimon Weiss Leticia González Geraldine L. Richmond George M. Whitesides Hardy Gross William Schopf Itamar Willner David Harel Helmut Schwarz Xiaoliang Sunney Xie Jim Heath Mordechai (Moti) Segev Omar M. Yaghi Joshua Jortner Michael Sela Ada Yonath Biographies and Abstracts (Arranged in alphabetic order) The Grand Challenges in the Chemical Sciences Dorit Aharonov The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Quantum Physics through the Computational Lens While the jury is still out as to when and where the impressive experimental progress on quantum gates and qubits will indeed lead one day to a full scale quantum computing machine, a new and not-less exciting development had been taking place over the past decade. -

Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions: Over 20 Years of European Support for Researchers’ Work

Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions: Over 20 years of European support for researchers’ work Since 1994, the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions have provided grants to train excellent researchers at all stages of their careers - be they doctoral candidates or highly experienced researchers – while encouraging transnational, inter-sectoral and interdisciplinary mobility. In 1996, the programme was named after the double Nobel Prize winner Marie Skłodowska-Curie to honour and spread the values she stood for. To date, more than 120 000 researchers have participated in the programme with many more benefiting from it – among them nine Nobel laureates and an Oscar winner. Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions in the future Building on the success of the programme over more than twenty years, the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions will continue to fund a new generation of outstanding, early-career researchers under Horizon Europe, the new European research and innovation programme for 2021-2027. The Commission has proposed a budget of EUR 6.8 billion for Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions under Horizon Europe which will now be the subject of negotiations with the European Parliament and Council. Stakeholders will have an opportunity to have their say in autumn 2018 to help shape the specific Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions funding schemes for the period 2021-2027. WHY WERE THE MARIE SKŁODOWSKA- as organisations involved in research: academic CURIE ACTIONS CREATED? institutions, international research organisations, private businesses and NGOs. The Marie Skłodowska- Research and innovation are the backbone of the Curie Actions are open to excellent researchers in all economy. Scientific discoveries drive the development disciplines, from fundamental research to market of new products and services, boosting economic growth take-up and innovation services. -

Nfap Policy Brief » October 2019

NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR AMERICAN POLICY NFAP POLICY BRIEF» OCTOBER 2019 IMMIGRANTS AND NOBEL PRIZES : 1901- 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Immigrants have been awarded 38%, or 36 of 95, of the Nobel Prizes won by Americans in Chemistry, Medicine and Physics since 2000.1 In 2019, the U.S. winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics (James Peebles) and one of the two American winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry (M. Stanley Whittingham) were immigrants to the United States. This showing by immigrants in 2019 is consistent with recent history and illustrates the contributions of immigrants to America. In 2018, Gérard Mourou, an immigrant from France, won the Nobel Prize in Physics. In 2017, the sole American winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was an immigrant, Joachim Frank, a Columbia University professor born in Germany. Immigrant Rainer Weiss, who was born in Germany and came to the United States as a teenager, was awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics, sharing it with two other Americans, Kip S. Thorne and Barry C. Barish. In 2016, all 6 American winners of the Nobel Prize in economics and scientific fields were immigrants. Table 1 U.S. Nobel Prize Winners in Chemistry, Medicine and Physics: 2000-2019 Category Immigrant Native-Born Percentage of Immigrant Winners Physics 14 19 42% Chemistry 12 21 36% Medicine 10 19 35% TOTAL 36 59 38% Source: National Foundation for American Policy, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, George Mason University Institute for Immigration Research. Between 1901 and 2019, immigrants have been awarded 35%, or 105 of 302, of the Nobel Prizes won by Americans in Chemistry, Medicine and Physics. -

CHEMISTRY ONLINE BOOKS COLLECTION Wiley Is Committed to Extending the World’S Chemistry Knowledge Through Publishing Diverse and Extensive 3,300+ Resources

CHEMISTRY ONLINE BOOKS COLLECTION Wiley is committed to extending the world’s chemistry knowledge through publishing diverse and extensive 3,300+ resources. We work with renowned authors, editors Titles and reviewers to deliver content in the way you need it. This collection comprises work that will enhance teaching and research, and provide students and researchers with a vast range of reliable, authoritative content- all available to access Including over 3,300 within your library’s digital resources. titles with no DRM restrictions, this collection offers a reliable and high- impact route to expand or enhance your digital INTERDISCIPLINARY: resources in Chemistry. Titles published each year span Analytical Chemistry, Environmental Chemistry, Industrial Chemistry, Catalysis, Chemical Safety, Pharmaceutical & Medicinal Chemistry, Organic & Inorganic Chemistry, Green Chemistry & Sustainability, Energy, Physical Chemistry, Chemical Engineering, and many more areas. 97% of the world’s Nobel AUTHORITATIVE: Prize Laureates 97% of the world’s Nobel Prize Laureates in in Chemistry have Chemistry have published with Wiley, including published with seminal works from the 2016 Nobel Prize winning Wiley authors, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart, Jean-Pierre Sauvage, and Bernard L. Feringa. EJ Corey, Gerhard Ertl, Robert Grubbs, George Olah, Martin Chalfie, and several other Nobel Laureates from all sections of chemistry add their names to Wiley’s distinguished list of authors. Wiley also publishes works from numerous recipients of other major prestigious awards in Chemistry, from leading societies such as the American Chemical Society, Royal Society of Chemistry, and GDCh. INCLUSIVE: Used by scholars and faculty for their own research, but also by lecturers and their students looking for citable, informative, and trustworthy content. -

Open Letter to the American People

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: October 18, 2016 AN OPEN LETTER TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE The coming Presidential election will have profound consequences for the future of our country and the world. To preserve our freedoms, protect our constitutional government, safeguard our national security, and ensure that all members of our nation will be able to work together for a better future, it is imperative that Hillary Clinton be elected as the next President of the United States. Some of the most pressing problems that the new President will face — the devastating effects of debilitating diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and cancer, the need for alternative sources of energy, and climate change and its consequences — require vigorous support for science and technology and the assurance that scientific knowledge will inform public policy. Such support is essential to this country’s economic future, its health, its security, and its prestige. Strong advocacy for science agencies, initiatives to promote innovation, and sensible immigration and education policies are crucial to the continued preeminence of the U.S. scientific work force. We need a President who will support and advance policies that will enable science and technology to flourish in our country and to provide the basis of important policy decisions. For these reasons and others, we, as U.S. Nobel Laureates concerned about the future of our nation, strongly and fully support Hillary Clinton to be the President of the United States. Peter Agre, Chemistry 2003 Carol W. Greider, Medicine 2009 Sidney Altman, Chemistry 1989 David J. Gross, Physics 2004 Philip W. Anderson, Physics 1977 Roger Guillemin, Medicine 1977 Kenneth J. -

Structure Matters

the protein crystallographer’s ultimate lab automation bundle protein crystallisation 3 instruments year full 2 warranty set of unlimited 1 software licences do you have the steadiest hand in crystallography? take the loop master challenge at ACA 2017! discover more at www.ttplabtech.com fi nd us on ACA - Structure Matters www.AmerCrystalAssn.org Table of Contents 2 President’s Column 2-3 2017 IUCr Meeting & General Assembly Hyderabad 4 New ACA SIG for Cryo-EM 4-5 New ACA SIG for Best Practices for Data Analysis & Archiving 5 What's on the Cover 6-7 News from Canada What's on the Cover Page 5 8 ACA History Site Update 8 Index of Advertisers 9-12 Living History - Alex Wlodawer 13 ACA New Orleans - Workshop on Communication & Innovation 14-15 ACA New Orleans - Workshop on Research Data Management 16 ACA New Orleans - Workshop on Crysalis & OLEX2 16 Contributors to this Issue 18 Spotlight on Stamps 19-20 ACA New Orleans - Travel Grant Recipients 21-23 Obituaries Election Results Isabella Karle (1921-2017) Henry Bragg (1919-2017) 24 News and Awards 24-25 CESTA 2017 - A Study of the Art of Symmetry 26-28 Update on Structural Dynamics 29 ACA Corporate Members 30 Book Reviews 31-33 ACA Elections Results for 2018 34 2017 Contributors to ACA Funds 35 Puzzle Corner 36-37 ACA 2018 NToronto - Preview 38 Call for Nominations 39 ACA 2018 Summer Course in Chemical Crystallography 40 Future Meetings Contributions to ACA RefleXions may be sent to either of the Editors: Please address matters pertaining to advertisements, Judith L. -

Highly Cited Researchers Are Among

Highly Cited 2019 Researchers Identifying top talent in the sciences and social sciences. Researcher Recognition Highly Cited Researchers are among Highly Cited Researchers 2019 Researchers Cited Highly those who have demonstrated significant and broad influence reflected in their publication of multiple papers, highly cited by their peers over the course of the last decade. These highly cited papers rank in the top 1% by citations for a chosen field or fields and year in Web of Science. Of the world’s population of scientists and social scientists, the Web of Science Group’s Highly Cited Researchers are one in 1,000. 2 Overview The list of Highly Cited Researchers 2019 from the Web of Science Group identifies scientists and social scientists who have demonstrated significant broad influence, reflected through their publication of multiple papers frequently cited by their peers during the last decade. Researchers are selected for their For the Highly Cited Researchers 2019 exceptional influence and performance analysis, the papers surveyed were the in one or more of 21 fields (those used most recent papers available to us – those in Essential Science Indicators,1 or ESI) published and cited during 2008-2018 and or across several fields. which at the end of 2018 ranked in the top 1% by citations for their ESI field and year 6,216 researchers are named Highly Cited (the definition of a highly cited paper). Researchers in 2019 – 3,725 in specific fields and 2,491 for cross-field performance. The threshold number of highly cited This is the second year that researchers with papers for selection differs by field, with cross-field impact have been identified. -

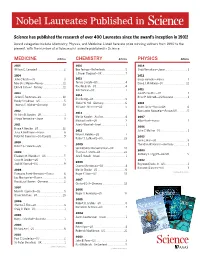

Nobel Laureates Published In

Nobel Laureates Published in Science has published the research of over 400 Laureates since the award’s inception in 1901! Award categories include Chemistry, Physics, and Medicine. Listed here are prize-winning authors from 1990 to the present, with the number of articles each Laureate published in Science. MEDICINE Articles CHEMISTRY Articles PHYSICS Articles 2015 2016 2014 William C. Campbell . 2 Ben Feringa —Netherlands........................5 Shuji Namakura—Japan .......................... 1 J. Fraser Stoddart—UK . 7 2014 2012 John O’Keefe—US...................................3 2015 Serge Haroche—France . 1 May-Britt Moser—Norway .......................11 Tomas Lindahl—US .................................4 David J. Wineland—US ............................12 Edvard I. Moser—Norway ........................11 Paul Modrich—US...................................4 Aziz Sancar—US.....................................7 2011 2013 Saul Perlmutter—US ............................... 1 2014 James E. Rothman—US ......................... 10 Brian P. Schmidt—US/Australia ................. 1 Eric Betzig—US ......................................9 Randy Schekman—US.............................5 Stefan W. Hell—Germany..........................6 2010 Thomas C. Südhof—Germany ..................13 William E. Moerner—US ...........................5 Andre Geim—Russia/UK..........................6 2012 Konstantin Novoselov—Russia/UK ............5 2013 Sir John B. Gurdon—UK . 1 Martin Karplas—Austria...........................4 2007 Shinya Yamanaka—Japan.........................3