Urswick and Its Christian Origins Explored

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting of Urswick Parish Council

1094 MINUTES OF URSWICK, BARDSEA AND STAINTON PARISH COUNCIL From the meeting held on Thursday 20th April 2017 Urswick Parish Room, 7.30pm Present: Cllr. L. Birchall, Cllr. P. Bolt, Cllr. D. Chamberlain, Cllr. J. Keen (Chairman), Cllr. M. Turner, Dr. P. Attree (Clerk). District and County councillors: J. Willis. Members of the public: 1 1. To receive and approve apologies for absence. Apologies for absence were received from Cllrs. N. Cowsill, J. Hannah & J. Winder. Cllr. Bolt gave apologies for his late arrival. RESOLVED: that the apologies be noted and the reasons noted. 2. Declarations of interests To receive declarations by elected and co-opted members of interests in respect of items on this agenda. None. 3. Requests for dispensations None. 4. To authorise the Chairman to sign as a correct record the minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 9th March 2017. RESOLVED: that the minutes of the meeting held on 9th March 2017 be signed by the Chairman as a true record. 5. To note progress on matters not on today’s agenda – for report and observation only (items requiring a decision to be placed on agenda of next meeting). The Clerk reported on the following: • Nuisance smell from sileage stored at land adjacent to Daisy Hill Cottage, Great Urswick - reported to Public Protection Team and logged. • Potholes on lanes used as alternative routes during roadworks at Lindal in Furness. • Site of the former Coot, Great Urswick. Untidy site reported to District Council, and obstruction to traffic sightlines reported to County Highways. • Ongoing enquiries regarding Greenbank Gardens site, Little Urswick. -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

Appendix 3 Objections.Pdf

Prof. Jim D. Marshall Earth, Ocean and Ecological Sciences School of Environmental Sciences University of Liverpool 4 Brownlow Street Liverpool L69 3GP United Kingdom 0151--794 5177 Commons Registration Authority Cumbria County Council Application CA13/22 9 February 2019 To whom it may concern Urswick Tarn - Retention of Common Land Status. I am writing this letter to oppose application CA13/22 which seeks to remove the common land status assigned to the land associated with the former chapel at Urswick Tarn. My research group and I have long standing interests in Urswick Tarn and other marl lakes in Northwest England and have published many papers in international scientific journals on the significance of the sediment records that are preserved there. Starting with the work of Professor Frank Oldfield in the 1950’s and 60’s Urswick Tarn and its surrounding marl bench has been studied by scientists from Liverpool and many other Universities (including Exeter, Edge Hill and King’s College London). This is a site of national and indeed international scientific importance. The marl sediments beneath the chapel land and in the lake basin record the changing vegetation, land use and climate of the site spanning the 10,000 years and more since the end of the last glaciation. Marl lakes of this sort are relatively rare and provide a unique combination of biological remains and chemical markers than can be used to reconstruct past environmental change. My own specialisation, oxygen and carbon stable isotope geochemistry, enable us to quantitatively reconstruct past changes in temperature, rainfall and carbon cycling. -

Urswick Parish Plan 2006

'" U-rswick PC1-rish Ncrl::ul"e's hand blessed this pal"ish with a beautLl and chamctel" which few can l"ival. Good fortune then favoul"ed us with fOl"ebeal"s whose cal"ing hand - and fol" ~ a few, with the ultimate saC1"ifice- .J ~I I passed on to us the splendoul" .. f I that we now shal"e. Let us not be found wanting in OUl"l"espect fol" what those who I went befol"e have left: behind, 01"in OUl"dutLl to those who will succeed us. MaLI theLl in theil" tU1"nl"evel"e it as a home, which compels theil" affection, and is worthLl of theil" ca1"e. .J1£//\Y)! f,~ ~ (/h"fii ) :J'Y"') ~ .I.{f G...J_~J/f URSWICK PARISH PLAN EDITION 1 2006 Contents I Introduction I 2 Spiritual Expression and Development 4 3 Listed Buildings in the Parish 5 4 Educating the Junior Citizens of the Parish 6 5 Employment in the Parish 6 6 Services IIIthe Parish 8 7 Parish Amenities 9 8 Community Groups and Associations 10 9 Surveys of Parish Residents' Concerns and Aspirations 12 10 ConcernsandActionPlans- Parishwideitems 14 11 ConcernsandActionPlans- Bardsea items 19 12 Concerns and Action Plans - Urswick villages items 22 13 ConcernsandActionPlans- StaintonwithAdgarleyitems 25 14 Acknowledgements 27 OISWICI PARISHPLAN 1 Introduction Located to the east of the A590 trunk road on the Furness Peninsula in Cumbria, the border of Urswick Parish is 1.7 miles south of Ulverston town centre and 3.4 miles north of Barrow in Furness town centre. -

Local Plan (2006)

& Alterations (Final Composite Plan) This document combines the South Lakeland Local Plan (adopted in 1997) and the Alterations to the Local Plan (adopted in March 2006) Lawrence Conway Strategic Director Customer Services Published September 2007 he South Lakeland Local Plan and Alterations (Final Composite Plan) T March 2007) brings together in a single document: • the South Lakeland Local Plan, adopted in 1997 • the Alterations to the Local Plan, adopted in March 2006 All three documents and further information on the Local Plan can be viewed or downloaded from the Council's website at www.southlakeland.gov.uk/planning This combined document brings together the relevant polices and supporting text from both the South Lakeland Local Plan and Local Plan Alterations for the convenience of readers, who previously had to refer to two separate documents. PREFACE It is important to note that the Council has not amended the contents of either document - both of which contain references, which while correct at the time of PREFACE their respective adoptions, but may now be dated. The Local Plan policies and text which have been added or altered (in whole or part) through the Local Plan Alterations are shown within grey shaded boxes. The Development Plan The South Lakeland Local Plan and Alterations to the Local Plan form part of the statutory Development Plan for South Lakeland District, outside the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales National Parks. It sets out land use policies to guide new development through granting of planning permission. The Development Plan also comprises the Cumbria and Lake District Joint Structure Plan, adopted in April 2006. -

Exploring the Ancient Capital of Furness

WALKING FOR ALL Exploring the Ancient Capital THE WALKS 1. Town, Church and Castle, 1½ miles of Furness Dalton, the ancient capital of Furness. Dalton dates on pavements. No gates or stiles. back to long before medieval times. It was the main centre after Furness Abbey. 2. Gill Dub, 1½ miles on pavements and grassy path. Dalton Castle dates from the 14th century, it was Five Gentle Walks built for protection from raiding Scots and used as 3. Standing Tarn, 1½ miles on pavements, a courthouse. It has many interesting features and is track and grass. Some stiles. Round Dalton open from 2pm to 5pm on Saturdays from Easter to October. 4. Parkers Pond, 2 miles on pavements and paths. Includes 36 steps up & 14 down. The Parish Church, near the Castle, was built in the late 5. Abbey Paths, 2 miles 1800s. It has unusual chequerboard stonework. The on a footpath with gates and pavements stained glass windows may have come from Furness or on footpaths with gates and a field. Abbey. You can ‘Walk your way to Health’ on several George Romney, the famous portrait painter was buried weekly walks in the Furness area. in the churchyard in 1802. He was popular alongside For details contact Richard Scott Reynolds. In London, he was said to be involved with t: 01229 823144 Lady Hamilton whilst having a wife in Kendal. e: [email protected] or see w: www.whi.org.uk Written by Jean Povey Printed by Fingerprints This leaflet supported by Barrow Borough Council Dalton with Newton Town Council Peninsulas Tourism Partnership Wal ing to Health FEET FIRST IN FURNESS Drive. -

Ossick Coots and Collared Doves

Ossik Coots and Collared Doves The story of an amazing community and its church – from the beginning. By Reverend Colin R Honour. M.Ed. 1 Copyright (c) 2011 Colin R Honour The right of Colin Honour to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the written permission of the author. 2 to all the ‘characters’ who have made this church and parish what it is. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank our special friends at Urswick for introducing me to its remarkable past and sharing a vision for its future, and to the original Hidden Light Project Group for all we shared together in good times and bad. To Steve Dickinson, local archaeologist, for firing my imagination in the early days, and for permission to reproduce his line drawings of the inscribed stones in the church’s north wall from ‘Beacon on the Bay’, and photographs of the ‘threshold stone’ between tower and nave exposed in 2003. To Sir Roy Strong for introducing the ‘wider picture’ in a way we can all understand, and for allowing me to quote from his little gem, ‘A Little History Of The English Country Church’. Thanks go to the patient Archivist and Staff at the Barrow Central Library Local Resources Section, and also at Kendal Library, for their willingness to go the extra mile for me. -

Minutes of Urswick, Bardsea and Stainton Parish Council

1027 MINUTES OF URSWICK, BARDSEA AND STAINTON PARISH COUNCIL From the meeting held on Thursday 21 st May 2015 Stainton Recreation Hall, 7.30pm Present: Cllr. J. Keen, Cllr. D. Chamberlain, Cllr. N. Cowsill, Cllr. D. Stubbs, Cllr. J. Winder, Dr. P. Attree (Clerk). County/District councillors: Cllr. J Airey, Cllr. A. Butcher, Cllr. J. Willis Members of public: 1 1. To receive and approve apologies for absence. Apologies for absence were received from Cllrs. J. Kilty, S. Sweeting and C. Airey . RESOLVED: that the apologies be noted and the reasons noted. 2. Declarations of interests To receive declarations by elected and co-opted members of interests in respect of items on this agenda. None. 3. Requests for dispensations. None. 4. To authorise the chairman to sign as a correct record the minutes of the meeting held on 9th April 2015. RESOLVED: that the minutes of the meeting held on 9th April 2015 be signed by the Chairman as a true record. 5. To note progress on matters not on today’s agenda – for report and observation only (items requiring a decision to be placed on agenda of next meeting). The Clerk reported on the following: Trees at Bankfield overhanging road have been reported to the arboroculturist at SLDC, who is contacting the land owners. Fallen branches have also been reported to the police. Gateway at Skeldon Moor – Clerk again contacted the Planning Department, who are awaiting a valid planning application. Cllr.J. Airey to follow up. Cllr. Willis noted that work on the Coot junction at Great Urswick will be carried out in the near future. -

Church of Low Furness Community Magazine

CHURCH OF LOW FURNESS COMMUNITY MAGAZINE IN THIS ISSUE: The Meaning of Christmas Reconciliation Crossword based on "The Messiah" Mountain Pilgrims Diary of events for December 2019 and January 2020 DECEMBER 2019 & JANUARY 2020 Issue 3 EDITORIAL CHURCH OF LOW FURNESS EDITORIAL COMMUNITY MAGAZINE - DECEMBER 2019 & JANUARY 2020 ISSUE 3 I am writing this on the last Sunday of the Church's liturgical year when we celebrate Christ the King. The epistle appointed for today is Colossians 1, 11-20, and I have found CONTENTS Lunch Club & Family Film Club that the final two verses keep coming back to me: For God was pleased to have all his P 1 Cover illustration & title banners are Coffee Mornings: Bardsea, Rampside fullness dwell in him [Jesus Christ], and through him to reconcile to himself all things & Urswick of Neapolitan Crib at the Basilica whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood shed on of SS. Cosmos & Damian in Rome. Outreach Post Office Toddler Group - Rampside the cross. If the Son of Man laid down his life that man might be reconciled with God, what P 3 Editorial, Ladies Lunch Bunch are we giving to our fellow men that we might be reconciled one with another in such a P 4 SECTION 1 - Love for God Crafts & Company troubled world? That thought is not at the forefront of political discussion as we approach P 4 View from the Vicarage P27 Children's Gate - Urswick the General Election, but until it is the likelihood that reconciliation will happen between the Archbishop's Reconciliation Course P 5 "Blue Christmas" healing service holders of the very disparate views that prevail in our world is low. -

DNOP Furness Peninsula

South Lakeland District Council Election of District Councillor for the FURNESS PENINSULA Ward NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. The following persons have been and stand validly nominated: SURNAME OTHER NAMES HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION NAMES OF THE PROPOSER (P), (if any) SECONDER (S) AND THE PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE NOMINATION PAPER BUTCHER Andrew Clifford 150 North Lonsdale Conservative James Airey(P), Caroline Airey(S), Road, Ulverston, Party Candidate Angela Scrogham, Michael Wood, Sheila Cumbria, LA12 9DZ A. Wood, Anne W. Wren, Ian Edmondson, Ian F. Sweeting, Amanda L. Sweeting, Toby I Sweeting HOWLETT Peter Alan Wendelin, Pennington, Green Party Ruth Howlett(P), Gregory J. Ulverston, Cumbria, Thompson(S), Douglas Riley, Gail Riley, LA12 7NY Kerry A. Thistlethwaite, Trevor J. Thistlethwaite, Kevin W. Haley, Margaret J. Wood, Lucy Thompson, Ann Thomson HUNT Eirik Raymond Haugsbak 23a Cartmel Drive, Labour Party J. Mark Wilson(P), Shirley-Anne Ulverston, Cumbria, Wilson(S), Janet Caine, Bryan Caine, LA12 9PU Jean Phizacklea, Kathleen Gillgrass, Robert Bromley Gillgrass, Pauline Wall, Geoffrey Richard Dobson, Marian Dawson WILLIS Janet 1 Goose Green, Dalton- Liberal Alexandra Phillips(P), David E. in-Furness, Cumbria, Democrats Lancaster(S), Edith A. Burrow, Betty A. LA15 8LQ Holme, Susan Denison, Ian C. Wharton, Brian Robert Campbell, Rebecca L Thomas, Jane Carson, Gwenda J. Sykes 2. A POLL for the above election will be held on Thursday, 2nd May 2019 between the hours of 7.00am and 10.00pm 3. The number to be elected is ONE -

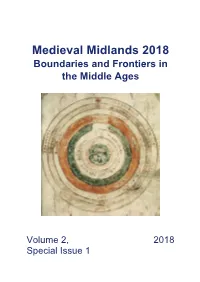

Medieval Midlands 2018 Boundaries and Frontiers in the Middle Ages

Medieval Midlands 2018 Boundaries and Frontiers in the Middle Ages Volume 2, 2018 Special Issue 1 Cover Image. Basic schematic T-O mappa mundi within seven circles of the universe in MS. on vellum: Bede, De nature rerum. The circles are labelled, from outside in, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Sols, Venus, Mercury, Moon[?]. Shelfmark: MS. Canon. Misc. 560, fol. 23r. Dated between 1055 and 1074. Source: The Bodleian Libraries, Oxford. Accessed through Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mappa_Mundi_2_from_Bede,_De_natura_r erum.jpg. Used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Midlands Historical Review ISSN 2516-8568 Volume 2 (2018), Special Issue 1 Published by the Midlands Historical Review With thanks to the editorial board. Christopher Booth, Editor Emily Mills, Deputy Editor Jen Caddick, Website Manager Joseph Himsworth, Lead Editor (Research Articles) Darcie Mawby, Lead Editor (Research Articles) Jamie Smith, Lead Editor (Other Research Outputs) With thanks to the assistant editors David Civil David Robinson Kimberley Weir Marco Panato Paul Grossman Rhys Berry Thomas Black Harriet-Rose Haylett-McDowell Alexandra Hewitt Eleanor Hedger Oliver Dodd Sophie Cope Miranda Jones Jumana Ghannam Lucy Mounfield Zoe Screti Published by Midlands Historical Review © 2018 Midlands Historical Review Midlands Historical Review Founded 2017 Midlands Historical Review is an interdisciplinary, peer-reviewed, student-led journal which showcases the best student research in the Arts and Humanities. It was founded in 2017 by a group of PhD students from diverse academic backgrounds and receives support from the University of Nottingham’s Department of History and School of Humanities. Students in the Arts and Humanities produce valuable contributions to knowledge which, once a degree has been awarded, are often forgotten. -

The Church of Low Furness Newsletter

The Church of Low Furness newsletter. Summer edition Church Services – July/August 2021 Date Church Service Time Sunday 27th June St. Cuthbert’s, Aldingham Holy Communion 10.30am Sunday 27th June St. Mary & St. Michael, Urswick Healing Service 6pm Sunday 4th July St. Mary & St. Michael, Urswick Holy Communion 10.30am Sunday 4th July St. Cuthbert’s, Aldingham Evening Prayer (BCP) 6pm Sunday 11th July Holy Trinity Church, Bardsea Holy Communion 10.30am Sunday 11th July By Aldingham Church (see notice below) Outdoor Family Service 2.30pm Sunday 18th July St. Mary & St. Michael, Urswick Service of the Word 10.30am Sunday 18th July St. Michael’s, Rampside Holy Communion 2.30pm Sunday 25th July St. Cuthbert’s, Aldingham Holy Communion 10.30am Sunday 25th July St. Mary & St. Michael, Urswick Healing Service 6pm Sunday 1st August St. Mary & St. Michael, Urswick Holy Communion 10.30am Sunday 1st August St. Cuthbert’s, Aldingham Evening Prayer (BCP) 6pm Sunday 8th August Holy Trinity Church, Bardsea Family Service 10.30am Sunday 15th August St. Mary & St. Michael, Urswick Service of the Word 10.30am Sunday 15th August St. Michael’s, Rampside Holy Communion 2.30pm Sunday 22nd August St. Cuthbert’s, Aldingham Holy Communion 10.30am Sunday 22nd August St. Mary & St. Michael, Urswick Healing Service 6pm Sunday 29th August Holy Trinity Church, Bardsea Holy Communion 10.30am Every Wednesday 10.30am Mid-week Communion service resumes in Urswick Church (not the Parish Room) When the weather is fine, refreshments are served in the Churchyard after the service Note: Masks are required to be worn during Church Services under Covid regulations Healing Services A service of prayer, contemplation, and healing.