Medieval Midlands 2018 Boundaries and Frontiers in the Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Diary Millom

Activities and Social Groups in the Millom Area Call the Helpline 08443 843 843 Old Customs House West Strand Whitehaven Cumbria CA28 7LR Fax: 01946 591182 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ageukwestcumbria.org.uk Reg. Charity no: 1122049 ‘Part of the Cumbria ‘Part of the Cumbria Health and Health and Social Social Wellbeing System’ Wellbeing System’ supported by Cumbria County supported by Cumbria Council County Council This social diary provides information on opportunities in the Social and Leisure Activities local community and on a wide range of services. It is listed by Access to a wide range of local social and activity groups activities. Support to help develop new activities in your local community Arts and Crafts Clubs: Volunteering opportunities Craft Group Opportunities to use your skills or develop new skills in Thwaites Village Hall, fortnightly, Wednesdays 2.00-4.00pm, Soup & supporting your community Pudding lunch available prior to group 12.00-1.30pm (no sessions during summer months restarts in September). Visit the Wide variety of volunteering roles Website: www.thwaitesvillagehall.co.uk Full training and on-going support Work experience placements Haverigg Sewing Group St. Luke’s Institute , St. Luke’s Road, Haverigg. Weekly Wednesdays Community befriending 7:30-9:30pm (Term time only). Contact Pam 07790116082 Linking you to friendship groups / other social activities Support to socialise, attend activity groups Kirksanton Art Group Support for those with hearing or visual impairments to join Kirksanton Village Hall, Kirksanton, weekly Tuesdays 1.00-3.00pm and Thursdays 6.30-8.30pm. Contact Dot Williams: 01229 776683 in local activities Kirksanton Quilters Group Home from hospital support Kirksanton Village Hall, Kirksanton. -

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Social Diary Millom

Activities and Social Groups in the Millom Area ‘Part of the Cumbria Health and Social Wellbeing System’ supported by Cumbria County Council This social diary provides information on opportunities in the local community and on a wide range of services. It is listed by activities. Arts and Crafts Clubs: Craft Group Thwaites Village Hall, fortnightly, Wednesdays 2.00-4.00pm, Soup & Pudding lunch available prior to group 12.00-1.30pm (no sessions during summer months restarts in September). Visit the Website: www.thwaitesvillagehall.co.uk Haverigg Sewing Group St. Luke’s Institute , St. Luke’s Road, Haverigg. Weekly Wednesdays 7:30-9:30pm (Term time only). Contact Pam 07790116082 Kirksanton Art Group Kirksanton Village Hall, Kirksanton, weekly Tuesdays 1.00-3.00pm and Thursdays 6.30-8.30pm. Contact Dot Williams: 01229 776683 Kirksanton Quilters Group Kirksanton Village Hall, Kirksanton. Fortnightly - Wednesdays 2.00 to 4.00 pm. No meetings in July & August. New visitors welcome. Contact: Mrs M Griffiths 01229 773983 Needles & Hooks Knitting and Crocheting group, come along and join in the fun or just call in for a natter and friendly advice. Millom Library, St George’s Road, Millom, weekly Mondays 2.00-4.00pm, refreshments provided 50p donation. Contact the Library: 01229 772445 Millom & District Flower Club A monthly programme of demonstrators showcasing their diverse floral artistry, plus None members always welcome. Pensioners Hall, Mainsgate Road, Millom. Meets monthly last Thursday of the month 7.00pm. Contact Mrs Cunningham: 01229 774283 or Mrs Maureen Gleaves 01229 778189 Dance Classes: Old Time / Sequence Dancing Masonic Hall, Cambridge Street, Millom, weekly Wednesdays 7.30- 9.00pm. -

23 Feb 2021 Visit England's Regional Coastlines in 2021 and Explore the Extraordinary Outdoors…

Visit England’s regional coastlines in 2021 and explore the extraordinary outdoors… L-R: Chale & Blackgang, Isle of Wight; Harwich Mayflower Trail, Essex; the view from Locanda on the Weir, Somerset; Eskdale Railway, Lake District 9 February 2021 For travel inspiration across England’s coastline, visit E nglandscoast.com/en, the browse-and-book tool that guides you along the coast and everything it has to offer, from walking routes and heritage sites to places to stay and family attractions. Plan a trip, build an itinerary and book directly with hundreds of restaurants, cafés, pubs, hotels, B&Bs and campsites. “The coastline of England can rival that of any on the planet for sheer diversity, cultural heritage and captivating beauty,” says Samantha Richardson, Director, National Coastal Tourism Academy, which delivers the England’s Coast project. “No matter where you live, this is the year to explore locally. Take in dramatic views across the cliff-tops, explore charming harbour towns and family-friendly resorts like Blackpool, Scarborough, Brighton, Margate or Bournemouth. “Or experience culture on England’s Creative Coast in the South East; wherever you visit, you’re guaranteed to discover something new. Walk a stretch of the England Coast Path, enjoy world-class seafood or gaze at the Dark Skies in our National Parks near to the coast; England’s Coast re-energises and inspires, just when we need it most.” Whether one of England’s wonderful regional coastlines is on your doorstep or you’re planning a trip later in 2021, here are some unmissable experiences to enjoy in each region this year along with ways to plan your trip with E nglandscoast.com/en. -

North West Inshore and Offshore Marine Plan Areas

Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2015 Marshall Paul Macrae 1.0 Paul Macrae Updated draft final report following stakeholder consultation, August 2018 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Paul Macrae Final report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

Levens Hall & Gardens

LAKE DISTRICT & CUMBRIA GREAT HERITAGE 15 MINUTES OF FAME www.cumbriaslivingheritage.co.uk Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal Cumbria Living Heritage Members’ www.abbothall.org.uk ‘15 Minutes of Fame’ Claims Cumbria’s Living Heritage members all have decades or centuries of history in their Abbot Hall is renowned for its remarkable collection locker, but in the spirit of Andy Warhol, in what would have been the month of his of works, shown off to perfection in a Georgian house 90th birthday, they’ve crystallised a few things that could be further explored in 15 dating from 1759, which is one of Kendal’s finest minutes of internet research. buildings. It has a significant collection of works by artists such as JMW Turner, J R Cozens, David Cox, Some have also breathed life into the famous names associated with them, to Edward Lear and Kurt Schwitters, as well as having a reimagine them in a pop art style. significant collection of portraits by George Romney, who served his apprenticeship in Kendal. This includes All of their claims to fame would occupy you for much longer than 15 minutes, if a magnificent portrait - ‘The Gower Children’. The you visited them to explore them further, so why not do that and discover how other major piece in the gallery is The Great Picture, a interesting heritage can be? Here’s a top-to-bottom-of-the-county look at why they triptych by Jan van Belcamp portraying the 40-year all have something to shout about. struggle of Lady Anne Clifford to gain her rightful inheritance, through illustrations of her circumstances at different times during her life. -

Community Led Plan 2019 – 2024

The Community Plan and Action Plan for Millom Without Parish Community Led Plan 2019 – 2024 1 1. About Our Parish Millom Without Parish Council is situated in the Copeland constituency of South West Cumbria. The Parish footprint is both in the Lake District National Park or within what is regarded as the setting of the Lake District National Park. This picturesque area is predominately pastoral farmland, open fell and marshland. Within its boundary are the villages of The Green, The Hill, Lady Hall and Thwaites. On the North West side, shadowed by Black Combe, is the Whicham Valley and to the South the Duddon Estuary. On its borders are the villages of Silecroft, Kirksanton, Haverigg, Broughton in Furness, Foxfield, Kirkby in Furness, Ireleth, Askam and the town of Millom. On the horizon are the Lake District Fells which include Coniston, Langdale and Scafell Ranges and is the gateway to Ulpha, Duddon and Lickle Valleys. Wordsworth wrote extensively of the Duddon, a river he knew and loved from his early years. The Parish has approximately 900 Residents. The main industry in this and surrounding areas is tourism and its relevant services. Farming is also predominant and in Millom there are a number of small industrial units. The Parish is also home to Ghyll Scaur Quarry. 2. Our Heritage Millom Without is rich in sites of both historic and environmental interest. Historic features include an important and spectacular bronze age stone circle at Swinside, the Duddon Iron furnace, and Duddon Bridge. The landscape of Millom Without includes the Duddon estuary and the views up to the Western and Central Lake District Fells. -

Classic Novels: Meeting the Challenge of Great Literature Parts I–III

Classic Novels: Meeting the Challenge of Great Literature Parts I–III Professor Arnold Weinstein THE TEACHING COMPANY ® Arnold Weinstein, Ph.D. Edna and Richard Salomon Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature, Brown University Born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1940, Arnold Weinstein attended public schools before going to Princeton University for his college education (B.A. in Romance Languages, 1962, magna cum laude). He spent a year studying French literature at the Université de Paris (1960−1961) and a year after college at the Freie Universität Berlin, studying German literature. His graduate work was done at Harvard University (M.A. in Comparative Literature, 1964; Ph.D. in Comparative Literature, 1968), including a year as a Fulbright Scholar at the Université de Lyon in 1966−1967. Professor Weinstein’s professional career has taken place almost entirely at Brown University, where he has gone from Assistant Professor to his current position as Edna and Richard Salomon Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature. He won the Workman Award for Excellence in Teaching in the Humanities in 1995. He has also won a number of prestigious fellowships, including a Fulbright Fellowship in American literature at Stockholm University in 1983 and research fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1998 (in the area of literature and medicine) and in 2007 (in the area of Scandinavian literature). In 1996, he was named Professeur Invité in American literature at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. Professor Weinstein’s -

The Seaside Resorts of Westmorland and Lancashire North of the Sands in the Nineteenth Century

THE SEASIDE RESORTS OF WESTMORLAND AND LANCASHIRE NORTH OF THE SANDS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY BY ALAN HARRIS, M.A., PH.D. READ 19 APRIL 1962 HIS paper is concerned with the development of a group of Tseaside resorts situated along the northern and north-eastern sides of Morecambe Bay. Grange-over-Sands, with a population in 1961 of 3,117, is the largest member of the group. The others are villages, whose relatively small resident population is augmented by visitors during the summer months. Although several of these villages have grown considerably in recent years, none has yet attained a population of more than approxi mately 1,600. Walney Island is, of course, exceptional. Since the suburbs of Barrow invaded the island, its population has risen to almost 10,000. Though small, the resorts have an interesting history. All were affected, though not to the same extent, by the construction of railways after 1846, and in all of them the legacy of the nineteenth century is still very much in evidence. There are, however, some visible remains and much documentary evidence of an older phase of resort development, which preceded by several decades the construction of the local railways. This earlier phase was important in a number of ways. It initiated changes in what were then small communities of farmers, wood-workers and fishermen, and by the early years of the nineteenth century old cottages and farmsteads were already being modified to cater for the needs of summer visitors. During the early phase of development a handful of old villages and hamlets became known to a select few. -

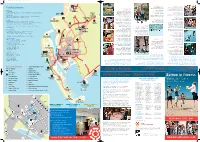

Barrow Map Leaflet 28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1

Barrow Map Leaflet_28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1 Tel: 01229 474251. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 430600. 01229 Tel: WC u School. Riding Seaview specially trained owls/bird of prey. of owls/bird trained specially by the sea with sea the by horse a Ride Travelling to Barrow 835449. 01229 Tel: ASKAM from displays regular as well as diverse night life. life. night diverse - see a variety of owls of variety a see - owls Furness - IN - trails. waymarked BY CAR q and lively having for reputation countryside and seaside and countryside which adds further to the town’s the to further adds which From The M6 FURNESS 824334. 01229 Tel: the network of network the A595 Walk on board the Princess Selandia, Princess the board on Leave the Motorway at junction 36, then follow the A590 all the way to Barrow. restaurant. family and ROANHEAD LINDAL state of the art floating nightspot floating art the of state - indoor play area play indoor - BEACH Warehouse Wacky - IN - courses. excellent 3 Barrow’s is Barrow’s latest Barrow’s is From The Lakes Lagoon Blue The enthusiasts can play on play can enthusiasts Golf Take the A592 from Bowness along the Eastern shore of Lake Windermere. FURNESS A590 823823. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 823823 01229 Tel: Lazerzone. of Join the A590 which takes you straight to Barrow. t SOUTH LAKES WILD eatery. stylish and WC 470303. 01229 Tel: bar, childrens play area and venue and area play childrens bar, - indoor play area area play indoor - ANIMAL PARK Playzone West Kitesurfing. West - stylish eatery, stylish - BY TRAIN House Custom The railway and play areas. -

William Le Fleming, Richard Le Fleming &C

CUMBERLAND & WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN & ARCHJEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. TRACT SERIES, No. XI. THE MEMOIRS OF SIR DANIEL FLEMING TRANSCRIBED BY R. E. PORTER AND EDITED BY W. G. COLLINGWOOD. KENDAL TITUS WILSON & SON 1928. KENDAL: PRINTED BY TITUS WILSON & SON, 28, Highgate. 1928. CONTENTS. PAGE... Editor's Preface Vll Sir Daniel Fleming, from the portrait at Rydal Hall . to /ace I The Earls of Flanders and the Flemings .. I Michael le Fleming of Furness .. 5 William f. Michael le Fleming and his family II Richard f. Michael le Fleming and the family of Beckermet . Richard f. John le Fleming and the family at Coniston and Beckermet . Thomas f. Thomas Fleming and the family at • Rydal and Coniston . 37 The Flemings of Conistori, Rydal and Skirwith · ... 56 William f. John Fleming, 1628-1649 .. 64 Daniel Fleming of Skirwith and his family 66 Sir Daniel Fleming, his autobiography 73 Description of Caernarvon Castle 81 Gleaston Castle .. 82 Coniston . 82 Rydal . 85 The arms belonging to the family of Fleming ~9 Sir Daniel Fleming's advice to his son 92 Appendix I ; Beckermet documents 98 Appendix II; Rydal documents .. I03 Appendix III ; Kirkland documents . Il2 Index . II8 EDITOR'S PREFACE. Our Society has already printed, in the Tract Series of which this volume is the latest, two short works by Sir Daniel Fleming of Rydal, his Surveys of Cumberland and of Westmorland. These Memoirs were long lost, and his own manuscript, if there was such in any complete form, is still unknown; but an early copy was found and transcribed by Mr. R. E. Porter, and with the leave of Stanley Hughes le Fleming Esq., of Rydal Hall, is now printed. -

Meeting of Urswick Parish Council

1094 MINUTES OF URSWICK, BARDSEA AND STAINTON PARISH COUNCIL From the meeting held on Thursday 20th April 2017 Urswick Parish Room, 7.30pm Present: Cllr. L. Birchall, Cllr. P. Bolt, Cllr. D. Chamberlain, Cllr. J. Keen (Chairman), Cllr. M. Turner, Dr. P. Attree (Clerk). District and County councillors: J. Willis. Members of the public: 1 1. To receive and approve apologies for absence. Apologies for absence were received from Cllrs. N. Cowsill, J. Hannah & J. Winder. Cllr. Bolt gave apologies for his late arrival. RESOLVED: that the apologies be noted and the reasons noted. 2. Declarations of interests To receive declarations by elected and co-opted members of interests in respect of items on this agenda. None. 3. Requests for dispensations None. 4. To authorise the Chairman to sign as a correct record the minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 9th March 2017. RESOLVED: that the minutes of the meeting held on 9th March 2017 be signed by the Chairman as a true record. 5. To note progress on matters not on today’s agenda – for report and observation only (items requiring a decision to be placed on agenda of next meeting). The Clerk reported on the following: • Nuisance smell from sileage stored at land adjacent to Daisy Hill Cottage, Great Urswick - reported to Public Protection Team and logged. • Potholes on lanes used as alternative routes during roadworks at Lindal in Furness. • Site of the former Coot, Great Urswick. Untidy site reported to District Council, and obstruction to traffic sightlines reported to County Highways. • Ongoing enquiries regarding Greenbank Gardens site, Little Urswick.