The Transformation of Leicester, C.1970-1990 Simon Gunn And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evaluation of the Leicester Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Strategy

The Evaluation of the Leicester Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Strategy Phase 2 Report Informed by the T.P.U. Deep Dive Findings Centre for Social Action January 2007 The Research Team Peer Evaluators Alexan Junior Castor Jordan Christian Jessica Hill Tina Lee Lianne Murray Mikyla Robins Sian Walker Khushbu Sheth Centre for Social Action Hannah Goodman Alison Skinner Jennie Fleming Elizabeth Barner Acknowledgements Thanks to: Practitioners who helped to arrange sessions with our peer researchers or parents Rebecca Knaggs Riverside Community College Michelle Corr New College Roz Folwell Crown Hills Community College Anna Parr Kingfisher Youth Club Louise McGuire Clubs for Young People Sam Merry New Parks Youth Centre Harsha Acharya Contact Project Vanice Pricketts Ajani Women and Girls Centre Naim Razak Leicester City PCT Kelly Imir New Parks STAR Tenant Support Team Laura Thompson Eyres Monsell STAR Tenant Support Team Young people who took part in the interviews Parents who took part in the interviews Practitioners who took part in the interviews, including some of the above and others Connexions PAs who helped us with recruitment Also: Teenage Pregnancy and Parenthood Partnership Board Mandy Jarvis Connexions Liz Northwood Connexions HR Kalpit Doshi The Jain Centre, Leicester Lynn Fox St Peters Health Centre Contents Page No. Acknowledgements Executive Summary 1 Methodology 7 Information from young people consulted at school and in the community 15 What Parents told us 30 What Practitioners told us 39 Perspectives from School Staff Consultation -

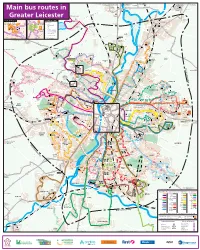

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Leicester Network Map Aug21

Sibson Rd Red Hill Lane Greengate Lane Lambourne Rd Greengate Lane Beacon Ave Beacon ip Ave B Link Rd Cropston Rd anl ra W Way Earls dg Link Rd a Elmfield Avenue t T e h Dalby Rd Church Hill Rd R u Oakfield Avenue Wanlip Ln d r c Fielding Rd Birstall Castle Hill Newark Rd a Johnson Rd l L 25 26 s Country Park il o t Edward St t dg s e o Andrew Rd Colby Dr Long Close A R n Melton Rd Albio d Rd Pinfold d n R on R Stadon Rd S i Link Rd t n d School Lane Road Ridgeway n en Beaumont Leys Lane Rd Birstall Hollow Rd o Thurmaston 21 Drive t B s Knights Road Went Rd op d r Beaumont R C Lodge Road Hoods Close h Hum g be L Madeline Rd Manor Rd rst Blount B r d Co-op u on adgate R e o e A46 Road i r L c Alderton r e ion Rd o a s n n D 74 en Leycroft Rd b Holt Rd Southdown Rd t Ave Curzon d Walkers e Anstey B h e Close Melton Rd Jacklin Drive r R y Mowmacre g b R k Beda l l u o e Ashfield d D o o r o ive T r C Drive Hill L h b u r Ave June Avenue e r h c d h et R Groby Rd t p Bord a ll Trevino Dr Roman Rd a r e Rushey Mead 4 e H o r s Great Central a M t st Verdale Beaumont D o ir r n Railway Hill Rise iv B Sainsbury’s Road Park Holderness Rd e R 14A d Oakland Gynsill Close Trevino Dr R Nicklaus Rd Cashm ed H Avenue Braemar Dr r or ill Way BarkbythorpeMountain Rd Gorse Hill Gorse D e 25 26 ck V Watermead Way wi iew Road Krefeld Wayer Thurcaston Rd Humberstone Lane Beaumont t Uxbridge Rd t Lockerbie W ug ypass u o Troon Way o h ern B odstock Rd Avenue r W t B C es 54 74 Leys Babington Marwood Rd Retro a o a y r W n d b te Tilling no s Computer R n -

List of Polling Stations for Leicester City

List of Polling Stations for Leicester City Turnout Turnout City & Proposed 2 Polling Parliamentary Mayoral Election Ward & Electorate development Stations Election 2017 2019 Acting Returning Officer's Polling Polling Place Address as at 1st with potential at this Number comments District July 2019 Number of % % additional location of Voters turnout turnout electorate Voters Abbey - 3 member Ward Propose existing Polling District & ABA The Tudor Centre, Holderness Road, LE4 2JU 1,842 750 49.67 328 19.43 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABB The Corner Club, Border Drive, LE4 2JD 1,052 422 49.88 168 17.43 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABC Stocking Farm Community Centre, Entrances From Packwood Road And Marwood Road, LE4 2ED 2,342 880 50.55 419 20.37 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABD Community of Christ, 330 Abbey Lane, LE4 2AB 1,817 762 52.01 350 21.41 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABE St. Patrick`s Parish Centre, Beaumont Leys Lane, LE4 2BD 2 stations 3,647 1,751 65.68 869 28.98 Polling Place remains unchanged Whilst the Polling Station is adequate, ABF All Saints Church, Highcross Street, LE1 4PH 846 302 55.41 122 15.76 we would welcome suggestions for alternative suitable premises. Propose existing Polling District & ABG Little Grasshoppers Nursery, Avebury Avenue, LE4 0FQ 2,411 1,139 66.61 555 27.01 Polling Place remains unchanged Totals 13,957 6,006 57.29 2,811 23.09 Aylestone - 2 member Ward AYA The Cricketers Public House, 1 Grace Road, LE2 8AD 2,221 987 54.86 438 22.07 The use of the Cricketers Public House is not ideal. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Leicester City

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Leicester City Report to the Electoral Commission June 2002 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND © Crown Copyright 2002 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report No: 295 2 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? 5 SUMMARY 7 1 INTRODUCTION 11 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 13 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 17 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 19 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 25 6 WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? 61 A large map illustrating the proposed ward boundaries for Leicester City is inserted inside the back cover of this report. BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND 3 4 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to the Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI 2001 No. 3692). The Order also transferred to the Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them. -

Interpreting Differential Health Outcomes Among Minority Ethnic Groups in Wave 1 and 2

Interpreting differential health outcomes among minority ethnic groups in wave 1 and 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. It is clear from ONS quantitative studies that all minority ethnic groups in the UK have been at higher risk of mortality throughout the Covid-19 pandemic (high confidence). Data on wave 2 (1st September 2020 to 31st January 2021) shows a particular intensity in this pattern of differential mortality among Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups (high confidence). 2. This paper draws on qualitative and sociological evidence to understand trends highlighted by the ONS data and suggests that the mortality rates in Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups are due to the amplifying interaction of I) health inequities, II) disadvantages associated with occupation and household circumstances, III) barriers to accessing health care, and IV) potential influence of policy and practice on Covid-19 health- seeking behaviour (high confidence). I) Health inequities 3. Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups suffer severe, debilitating underlying conditions at a younger age and more often than other minority ethnic groups due to health inequalities. They are more likely to have two or more health conditions that interact to produce greater risk of death from Covid-19 (high confidence). 4. Long-standing health inequities across the life course explain, in part, the persistently high levels of mortality among these groups in wave 2 (high confidence). II) Disadvantages associated with occupation and household circumstances 5. Occupation: Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities are more likely to be involved in: work that carries risks of exposure (e.g. retail, hospitality, taxi driving); precarious work where it is more difficult to negotiate safe working conditions or absence for sickness; and small-scale self-employment with a restricted safety net and high risk of business collapse (high confidence). -

Unemployment Bulletin April 2008

Unemployment Bulletin April 2008 Introduction The Unemployment Bulletin provides a monthly update of the latest unemployment and benefit data for Leicester and Leicestershire. The data is sourced from Nomis (www.nomisweb.co.uk) which contains data from the Office for National Statistics, the Department of Work and Pensions and other official sources. Some figures have been calculated by Leicestershire County Council and where this is the case it is stated in the source. There are a number of ways of measuring unemployment and this bulletin mainly focuses on the Claimant Count which is a measure of the number or proportion of people receiving Job Seekers Allowance (JSA) and National Insurance Credits at Jobcentre Plus local offices. This is not an official measure of unemployment but it is the only indicative statistic available for areas smaller than Local Authorities. Official estimates of unemployment in the UK are obtained from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) using the internationally agreed International Labour Organisation (ILO) definition. The ILO definition is based on the number of people without jobs who are looking for work and are available to start work (and includes people whether or not they are eligible to received unemployment related benefits). The LFS unemployment figures which are subject to sampling differences are not reliable at small areas. The Claimant Count is released on a monthly basis and is available down to ward level, so is used as a more current indicator of unemployment levels. Using the two sources together provides a more comprehensive picture of the labour market. There is a large degree of overlap between the Claimant Count and Unemployment (LFS ILO definition) although the latter figures are generally higher. -

Leicester City Labour Group City of Leicester New Ward Boundary Narrative

Patrick Kitterick For the attention of the Local Government Boundary Commission for England Please find attached the following files in relation to Leicester City Labour Party’s submission regarding the LGBCE’s review of boundaries for Leicester City Council. -PDF Map of the New City of Leicester Ward Boundaries as proposed by Leicester City Labour Party. -PDF Table of the numbers for each ward and variances for the New City of Leicester Ward Boundaries as proposed by Leicester City Labour Party. -Narrative on Proposed New Wards -Data files supplied by Leicester City Council which I believe are compatible with LGBCE systems which give the detailed data surrounding our proposals. If this is, in any way, incompatible with the supplied maps and narrative please contact me to resolve any confusion.. The overall approach of Leicester City Labour Party has been to produce a detailed, validated, city wide proposal for Leicester. We have used the River Soar as a primary definer of boundaries in the city, we have also made greater use of the railway lines in the city as a definer of boundaries and finally we have used major roads as a point to either divide wards or build wards depending on whether they divide communities or have communities grow around them. For the necessity of providing balanced numbers we have had to use minor roads as the final definer of boundaries. Overall we have reduced the number of wards from 22 to 20 and we have kept wards co-terminus with current parliamentary boundaries, as they too provide strong community and natural boundaries. -

Main Bus Routes in Central Leicestershire

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27.X27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 128 to Melton Mowbray 5 5.5A to 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray and Derby ROAD OAD SYSTON East SYSTON R 128 Rothley 27 Goscote 2 27 27 E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S 5A GA LA S OD -PA WO S BY HALLFIELD 5 N STO SY WESTFIELD LANE 126 127 Y A Rothley W 27 5 E S 128 AD S Queniborough O O R F N Central Leicestershire TIO STA 5 54.123 to Loughborough ATE ROA BRADG D 2 D Glenfield Hospital Beaumont OA BRAD R GATE ROAD 126.127 N SYSTON TO Centre EL 5 Leicester Leys D Skylink M A O 54 WAY 6 5A R D Y BE L X27 A LE 27 Leisure Centre E G A Stop Services N IC 123 O O E R H 128 1 TI ST IG W H A E T R S Y-PASS S H T 7 Cropston Reservoir B R 1 not in use E G E 2 Cropston R ERN 6 T O Thurcaston U T H S R A E D O W D T A 6 R Y I U R A O 2 14A, 40, 302 O E R Glenfield T W R 3 S B E 6 T C W I AN F H E LI Leicester Road L P E S R Y H G O AD S N UHL D B O U 2 A 100 K Hospital F 4 E Beaumont 54 O R E 123 O R A B R 55 L L D FOR RD. -

Leicester City Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment 2018 SUMMARY

Leicester City Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment 2018 SUMMARY DOCUMENT March 2018 1. Introduction The purpose of the Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment (PNA) is to: • identify pharmaceutical services currently available in the community and assess the need for them in future • provide information which helps with planning and commissioning pharmacy services • provide information which helps make a decision if someone applies to provide a new pharmacy The PNA is a legally required document which NHS England will use to make decisions about market entry of new pharmacies in the city. The local authority and local clinical commissioning group will also use the PNA to help identify any changes to the local pharmaceutical services they commission from pharmacies. This PNA has looked at pharmacies in Leicester in terms of what the needs of the people are in Leicester. It only includes community pharmacies, not hospital or prison pharmacies. For information about the detail of pharmacy provision, please see the detailed graphs and tables in the full PNA. 2. Health needs of the population of Leicester Leicester’s health needs are detailed in city’s Joint Strategic Needs Assessment, which has informed the development of the city’s Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy, developed by the Health and Wellbeing Board. The strategy’s priorities are: • Improve outcomes for children and young people • Reduce premature mortality • Support independence for people with long term conditions • Improve mental health and emotional resilience • Focus on the wider determinants -

Leicester City Liberal Democrats

Leicester City Liberal Democrats 8 November 2013 Alison Evison Review Manager Local Government Boundary Commission for England Layden House 76-86 Turnmill Street London EC1M 5LG Dear Ms Evison Liberal Democrat Proposals for the Electoral Review for the City of Leicester Please find enclosed our proposals for a city-wide scheme for this stage of the review. We hope that the Commission will find our work thus far useful. Where we have used whole polling districts as building blocks for proposed wards, we are sure of our electorate figures. Where we have divided polling districts, while we have attempted accuracy, we would ask that you check, and if necessary amend, our figures. Even where the 2012 electorate figures are correct, the 2019 figures will need amendment. If you have any questions, or would like further information, please do not hesitate to contact me. Yours sincerely Alan Fox Vice-Chair Leicester City Liberal Democrats cc. David Owen, Review Officer Liberal Democrat Proposals for the Electoral Review for the City of Leicester In putting forward a city-wide scheme of proposed wards at this stage of the electoral review, Leicester City Liberal Democrats aim to assist the Local Government Boundary Commission in its work. We have started out by looking at communities and neighbourhoods. Then we have tried to create around them, compact wards with good internal communications and strong boundaries. Some of the bigger neighbourhoods are too large for a single member ward, but none are so enormous that they need a three member ward. Some communities are just the right size for a single member ward. -

Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment & Five Year Land

Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment & Five Year Land Supply Update 2014 Introduction The purpose of this report is to update the Leicester City Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA). It sets out the assessment of deliverable housing land for the City for the five-year period 2014/15-2018/19 (1 April 2014 – 31 March 2019) and the following ten-year period 2019/20-2028/29. It represents a snapshot of this housing land supply as at 31st March 2014. The SHLAA has been produced in accordance with the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) (2012) and National Planning Practice Guidance (NPPG) (2014). The Housing Market Area (HMA) wide SHLAA Methodology Paper (2009) sets out how SHLAA’s across Leicestershire will be carried out in line with national guidance. This means there is a high level of consistency across the outcomes of the SHLAA’s across the Leicestershire HMA. This local methodology is currently being revised following the publication of the NPPF and NPPG, and is expected to be finalised later in 2014. Future SHLAA updates will be produced in accordance with the updated local methodology. The original 2009 SHLAA report and methodology can be viewed at www.leicester.gov.uk/shlaa. The main role of the assessment is to: Identify sites and broad locations with potential for housing development; Assess their development potential; and Assess their suitability for development and the likelihood of development coming forward (availability and achievability). It should be noted that whilst the SHLAA is an important evidence base to inform plan making, it does not in itself determine whether or not a site should be granted planning permission or allocated for housing development.