Leicester Migration Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Branch Is Closing – but We're Still Here to Help

1 | 1 This branch is closing – but we’re still here to help Our Leicester Highfields branch is closing on Friday 11 December 2020. Branch closure feedback, and alternative ways to bank 2 | 3 Sharing branch closure feedback We’re now nearing the closure of the Leicester Highfields branch of Barclays. Our first booklet explained why the branch is closing, and gave information on other banking services that we hope will be convenient for you. We do understand that the decision to close a branch affects different communities in different ways, so we’ve spoken to people in your community to listen to their concerns. We wanted to find out how your community, and particular groups within it, could be affected when the branch closes, and what we could do to help people through the transition from using the branch with alternative ways to carry out their banking requirements. There are still many ways to do your banking, including in person at another nearby branch, at your local Post Office or over the phone on 0345 7 345 3452. You can also go online to barclays.co.uk/waystobank to learn about your other options. Read more about this on page 6. If you still have any questions or concerns about these changes, now or in the future, then please feel free to get in touch with us by: Speaking to us in any of our nearby branches Contacting Amanda Allan, your Market Director for East Midlands. Email: [email protected] We contacted the following groups: We asked each of the groups 3 questions – here’s what they said: MP: Jonathan Ashworth In your opinion, what’s the biggest effect that this branch closing will have on your local Local council: community? Leicester City Council – Councillors Sharmen Rahman, Kirk Master and Aminur Thalukdar You said to us: There were some concerns that the branch Community groups: closure may have an impact on the way both Age UK businesses and personal customers can bank. -

The Evaluation of the Leicester Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Strategy

The Evaluation of the Leicester Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Strategy Phase 2 Report Informed by the T.P.U. Deep Dive Findings Centre for Social Action January 2007 The Research Team Peer Evaluators Alexan Junior Castor Jordan Christian Jessica Hill Tina Lee Lianne Murray Mikyla Robins Sian Walker Khushbu Sheth Centre for Social Action Hannah Goodman Alison Skinner Jennie Fleming Elizabeth Barner Acknowledgements Thanks to: Practitioners who helped to arrange sessions with our peer researchers or parents Rebecca Knaggs Riverside Community College Michelle Corr New College Roz Folwell Crown Hills Community College Anna Parr Kingfisher Youth Club Louise McGuire Clubs for Young People Sam Merry New Parks Youth Centre Harsha Acharya Contact Project Vanice Pricketts Ajani Women and Girls Centre Naim Razak Leicester City PCT Kelly Imir New Parks STAR Tenant Support Team Laura Thompson Eyres Monsell STAR Tenant Support Team Young people who took part in the interviews Parents who took part in the interviews Practitioners who took part in the interviews, including some of the above and others Connexions PAs who helped us with recruitment Also: Teenage Pregnancy and Parenthood Partnership Board Mandy Jarvis Connexions Liz Northwood Connexions HR Kalpit Doshi The Jain Centre, Leicester Lynn Fox St Peters Health Centre Contents Page No. Acknowledgements Executive Summary 1 Methodology 7 Information from young people consulted at school and in the community 15 What Parents told us 30 What Practitioners told us 39 Perspectives from School Staff Consultation -

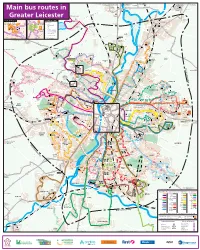

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Local Footie

Keeping you up to date with Evington’s news The newspaper of Friends of Evington. Charity no. 1148649 Issue 260 June/July/August 2016 Circulation 5,900 BELTANE SPRING FAYRE For the third year running, the Beltane Spring Fayre Group held this wonderful free event in Evington Park on 30th April. The schedule for the day included a yoga session from EvingtonÕs Yoga group, Maypole dancing with Brian and Rhona, an exhibition of owls and hawks from Kinder Falcons, a May Queen, open mic. ,music and poetry with the enchanting Evington singer Sam Tyler, Sheila and Merryl from Tangent Poets and musicians from Green Shoots. A variety of stalls included Vista for those with sight difficulties, RECOVERY assistance dogs, and Evington in Bloom with their plants. 19th Leicester Scouts provided space for drumming workshops and the day was filled with an array of talks and workshops by local pagan experts and storytellers. A pop up tea shop for refreshments and a splendid lunch, provided by Friends of Evington, sponsored by Evington Fish, organised and served by volunteers from Friends of Evington, added to the day. Beltane, the festival of Spring, celebrates the season and the start of summer. The Fayre, open to all, involves local communities for a fun day out. The organisers endeavour to promote understanding between the diverse spiritual communities of Leicester and actively welcome representatives of different faiths or none at their meetings and gatherings. Lesley Vann and Tony Modinos of The Beltane Spring Fayre Group (Composed of Pagans, people of all faiths and none, who celebrate the seasons) thank Leicester City Council and the Evington community for helping to make this traditional community event such a success. -

Leicester Network Map Aug21

Sibson Rd Red Hill Lane Greengate Lane Lambourne Rd Greengate Lane Beacon Ave Beacon ip Ave B Link Rd Cropston Rd anl ra W Way Earls dg Link Rd a Elmfield Avenue t T e h Dalby Rd Church Hill Rd R u Oakfield Avenue Wanlip Ln d r c Fielding Rd Birstall Castle Hill Newark Rd a Johnson Rd l L 25 26 s Country Park il o t Edward St t dg s e o Andrew Rd Colby Dr Long Close A R n Melton Rd Albio d Rd Pinfold d n R on R Stadon Rd S i Link Rd t n d School Lane Road Ridgeway n en Beaumont Leys Lane Rd Birstall Hollow Rd o Thurmaston 21 Drive t B s Knights Road Went Rd op d r Beaumont R C Lodge Road Hoods Close h Hum g be L Madeline Rd Manor Rd rst Blount B r d Co-op u on adgate R e o e A46 Road i r L c Alderton r e ion Rd o a s n n D 74 en Leycroft Rd b Holt Rd Southdown Rd t Ave Curzon d Walkers e Anstey B h e Close Melton Rd Jacklin Drive r R y Mowmacre g b R k Beda l l u o e Ashfield d D o o r o ive T r C Drive Hill L h b u r Ave June Avenue e r h c d h et R Groby Rd t p Bord a ll Trevino Dr Roman Rd a r e Rushey Mead 4 e H o r s Great Central a M t st Verdale Beaumont D o ir r n Railway Hill Rise iv B Sainsbury’s Road Park Holderness Rd e R 14A d Oakland Gynsill Close Trevino Dr R Nicklaus Rd Cashm ed H Avenue Braemar Dr r or ill Way BarkbythorpeMountain Rd Gorse Hill Gorse D e 25 26 ck V Watermead Way wi iew Road Krefeld Wayer Thurcaston Rd Humberstone Lane Beaumont t Uxbridge Rd t Lockerbie W ug ypass u o Troon Way o h ern B odstock Rd Avenue r W t B C es 54 74 Leys Babington Marwood Rd Retro a o a y r W n d b te Tilling no s Computer R n -

25 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

25 bus time schedule & line map 25 Leicester View In Website Mode The 25 bus line Leicester has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Leicester: 5:48 AM - 10:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 25 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 25 bus arriving. Direction: Leicester 25 bus Time Schedule 54 stops Leicester Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:45 AM - 10:10 PM Monday 5:48 AM - 10:10 PM Haymarket Bus Station, Leicester Charles Street, Leicester Tuesday 5:48 AM - 10:10 PM Orchard Street, Leicester Wednesday 5:48 AM - 10:10 PM 170 Belgrave Gate, Leicester Thursday 5:48 AM - 10:10 PM George Street, Leicester Friday 5:48 AM - 10:10 PM Foundry Square, Leicester Saturday 6:02 AM - 10:10 PM Leicester College, Belgrave Painter Street, Leicester Abbey Park Street, Belgrave 30 Belgrave Road, Leicester 25 bus Info Direction: Leicester Donaldson Road, Belgrave Stops: 54 70 Belgrave Road, Leicester Trip Duration: 55 min Line Summary: Haymarket Bus Station, Leicester, Law Street, Belgrave Orchard Street, Leicester, George Street, Leicester, Leicester College, Belgrave, Abbey Park Street, Ellis Avenue, Belgrave Belgrave, Donaldson Road, Belgrave, Law Street, Belgrave, Ellis Avenue, Belgrave, Shaftesbury Avenue, Shaftesbury Avenue, Belgrave Belgrave, Shirley Street, Belgrave, Victoria Road North, Belgrave, Bath Street, Belgrave, Church Road, Shirley Street, Belgrave Belgrave, Talbot Street, Belgrave, Abbey Lane, Belgrave, Barnwell Avenue, Belgrave, Belgrave Victoria Road North, Belgrave Boulevard, -

List of Polling Stations for Leicester City

List of Polling Stations for Leicester City Turnout Turnout City & Proposed 2 Polling Parliamentary Mayoral Election Ward & Electorate development Stations Election 2017 2019 Acting Returning Officer's Polling Polling Place Address as at 1st with potential at this Number comments District July 2019 Number of % % additional location of Voters turnout turnout electorate Voters Abbey - 3 member Ward Propose existing Polling District & ABA The Tudor Centre, Holderness Road, LE4 2JU 1,842 750 49.67 328 19.43 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABB The Corner Club, Border Drive, LE4 2JD 1,052 422 49.88 168 17.43 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABC Stocking Farm Community Centre, Entrances From Packwood Road And Marwood Road, LE4 2ED 2,342 880 50.55 419 20.37 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABD Community of Christ, 330 Abbey Lane, LE4 2AB 1,817 762 52.01 350 21.41 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABE St. Patrick`s Parish Centre, Beaumont Leys Lane, LE4 2BD 2 stations 3,647 1,751 65.68 869 28.98 Polling Place remains unchanged Whilst the Polling Station is adequate, ABF All Saints Church, Highcross Street, LE1 4PH 846 302 55.41 122 15.76 we would welcome suggestions for alternative suitable premises. Propose existing Polling District & ABG Little Grasshoppers Nursery, Avebury Avenue, LE4 0FQ 2,411 1,139 66.61 555 27.01 Polling Place remains unchanged Totals 13,957 6,006 57.29 2,811 23.09 Aylestone - 2 member Ward AYA The Cricketers Public House, 1 Grace Road, LE2 8AD 2,221 987 54.86 438 22.07 The use of the Cricketers Public House is not ideal. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Leicester City

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Leicester City Report to the Electoral Commission June 2002 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND © Crown Copyright 2002 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report No: 295 2 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? 5 SUMMARY 7 1 INTRODUCTION 11 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 13 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 17 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 19 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 25 6 WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? 61 A large map illustrating the proposed ward boundaries for Leicester City is inserted inside the back cover of this report. BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND 3 4 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to the Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI 2001 No. 3692). The Order also transferred to the Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them. -

Interpreting Differential Health Outcomes Among Minority Ethnic Groups in Wave 1 and 2

Interpreting differential health outcomes among minority ethnic groups in wave 1 and 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. It is clear from ONS quantitative studies that all minority ethnic groups in the UK have been at higher risk of mortality throughout the Covid-19 pandemic (high confidence). Data on wave 2 (1st September 2020 to 31st January 2021) shows a particular intensity in this pattern of differential mortality among Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups (high confidence). 2. This paper draws on qualitative and sociological evidence to understand trends highlighted by the ONS data and suggests that the mortality rates in Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups are due to the amplifying interaction of I) health inequities, II) disadvantages associated with occupation and household circumstances, III) barriers to accessing health care, and IV) potential influence of policy and practice on Covid-19 health- seeking behaviour (high confidence). I) Health inequities 3. Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups suffer severe, debilitating underlying conditions at a younger age and more often than other minority ethnic groups due to health inequalities. They are more likely to have two or more health conditions that interact to produce greater risk of death from Covid-19 (high confidence). 4. Long-standing health inequities across the life course explain, in part, the persistently high levels of mortality among these groups in wave 2 (high confidence). II) Disadvantages associated with occupation and household circumstances 5. Occupation: Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities are more likely to be involved in: work that carries risks of exposure (e.g. retail, hospitality, taxi driving); precarious work where it is more difficult to negotiate safe working conditions or absence for sickness; and small-scale self-employment with a restricted safety net and high risk of business collapse (high confidence). -

162 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

162 bus time schedule & line map 162 Leicester - New Parks (Tatlow Road) View In Website Mode The 162 bus line (Leicester - New Parks (Tatlow Road)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Leicester: 8:22 AM - 5:01 PM (2) New Parks: 7:50 AM - 5:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 162 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 162 bus arriving. Direction: Leicester 162 bus Time Schedule 31 stops Leicester Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:22 AM - 5:01 PM Liberty Road, New Parks Tuesday 8:22 AM - 5:01 PM Tournament Road, New Parks Tatlow Road, Groby Wednesday 8:22 AM - 5:01 PM Ibbeston Avenue, New Parks Thursday 8:22 AM - 5:01 PM Friday 8:22 AM - 5:01 PM Tatlow Road, New Parks Ibbetson Avenue, Groby Saturday Not Operational Cranstone Crescent, New Parks Cranstone crescent, Groby Forbes Close, New Parks 162 bus Info Forbes Close, Groby Direction: Leicester Stops: 31 Tournament Road, New Parks Trip Duration: 29 min Line Summary: Liberty Road, New Parks, Brex Rise, New Parks Tournament Road, New Parks, Ibbeston Avenue, Sacheverel Road, Leicester New Parks, Tatlow Road, New Parks, Cranstone Crescent, New Parks, Forbes Close, New Parks, Bringhurst Road, New Parks Tournament Road, New Parks, Brex Rise, New Parks, Frolesworth Road, Leicester Bringhurst Road, New Parks, Frolesworth Road, New Parks, Musson Road, New Parks, Knowles Road, Frolesworth Road, New Parks New Parks, Speers Road, New Parks, Aikman Avenue, New Parks, Dillon Way, New Parks, Dillon Musson Road, New -

St Denys Church, Church Road, Evington, Leicester. Le5 6Fa Hire Agreement and Conditions for Hire of the St Denys Parish Centre

ST DENYS CHURCH, CHURCH ROAD, EVINGTON, LEICESTER. LE5 6FA HIRE AGREEMENT AND CONDITIONS FOR HIRE OF THE ST DENYS PARISH CENTRE This Hire Agreement is made this day of 20 BETWEEN 1. The Parochial Church Council of St Denys Church Road Evington Leicester LE5 6FA (the PCC) by their agent and 2. Of (the Hirer) 3. The PCC and the Hirer have agreed that the Hirer shall hire the meeting room [and kitchen] at the St Denys Parish Centre (the Centre) Church Road Evington on the following terms which the Hirer agrees and has read or acknowledges having the opportunity to read. SIGNED by as Agent for the PCC SIGNED by The Hirer Hirer Tel no: Hirer email: PLEASE NOTE: Cheques to be made payable to St. Denys PCC and sent with the booking form to:- Mrs. Janette Pearson, Booking Secretary, 13 Earlswood Road, Evington, Leicester. LE5 6JB. Day(s) and date(s) required: Start Time(s): Finish Time(s): (This includes preparation time and clearing up time) Permitted Use: ONLY Permitted Numbers: 50 Maximum (if any seated) 80 maximum (if all standing) Hiring Fee (Total): £ Payments required as follows: 25% non-returnable deposit immediately on the Hirer signing of this agreement 25% Bond on the Hirer signing this agreement (returnable as provided in BOND below) 75% hiring fee not less than 14 days before the date required (in case of multiple hirings it shall be paid in full 14 days before the first hiring) In case of multiple hirings the 25% Bond shall be retained until after the last hiring date. -

Leicester City Labour Group City of Leicester New Ward Boundary Narrative

Patrick Kitterick For the attention of the Local Government Boundary Commission for England Please find attached the following files in relation to Leicester City Labour Party’s submission regarding the LGBCE’s review of boundaries for Leicester City Council. -PDF Map of the New City of Leicester Ward Boundaries as proposed by Leicester City Labour Party. -PDF Table of the numbers for each ward and variances for the New City of Leicester Ward Boundaries as proposed by Leicester City Labour Party. -Narrative on Proposed New Wards -Data files supplied by Leicester City Council which I believe are compatible with LGBCE systems which give the detailed data surrounding our proposals. If this is, in any way, incompatible with the supplied maps and narrative please contact me to resolve any confusion.. The overall approach of Leicester City Labour Party has been to produce a detailed, validated, city wide proposal for Leicester. We have used the River Soar as a primary definer of boundaries in the city, we have also made greater use of the railway lines in the city as a definer of boundaries and finally we have used major roads as a point to either divide wards or build wards depending on whether they divide communities or have communities grow around them. For the necessity of providing balanced numbers we have had to use minor roads as the final definer of boundaries. Overall we have reduced the number of wards from 22 to 20 and we have kept wards co-terminus with current parliamentary boundaries, as they too provide strong community and natural boundaries.