Examining the 2007 Redenomination of the Ghanaian Cedi on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code List 11 Invoice Currency

Code list 11 Invoice currency Alphabetical order Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region A BTN Bhutan ngultrum BOB Bolivian boliviano AFN Afghan new afghani BAM Bosnian mark ALL Albanian lek BWP Botswanan pula DZD Algerian dinar BRL Brazilian real USD American dollar BND Bruneian dollar AOA Angolan kwanza BGN Bulgarian lev ARS Argentinian peso BIF Burundi franc AMD Armenian dram AWG Aruban guilder AUD Australian dollar C AZN Azerbaijani new manat KHR Cambodian riel CAD Canadian dollar B CVE Cape Verdean KYD Caymanian dollar BSD Bahamian dollar XAF CFA franc of Central-African countries BHD Bahraini dinar XOF CFA franc of West-African countries BBD Barbadian dollar XPF CFP franc of Oceania BZD Belizian dollar CLP Chilean peso BYR Belorussian rouble CNY Chinese yuan renminbi BDT Bengali taka COP Colombian peso BMD Bermuda dollar KMF Comoran franc Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region CDF Congolian franc CRC Costa Rican colon FKP Falkland Islands pound HRK Croatian kuna FJD Fijian dollar CUC Cuban peso CZK Czech crown G D GMD Gambian dalasi GEL Georgian lari DKK Danish crown GHS Ghanaian cedi DJF Djiboutian franc GIP Gibraltar pound DOP Dominican peso GTQ Guatemalan quetzal GNF Guinean franc GYD Guyanese dollar E XCD East-Caribbean dollar H EGP Egyptian pound GBP English pound HTG Haitian gourde ERN Eritrean nafka HNL Honduran lempira ETB Ethiopian birr HKD Hong Kong dollar EUR Euro HUF Hungarian forint F I Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region ISK Icelandic crown LAK Laotian kip INR Indian rupiah -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

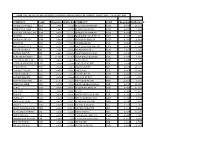

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

GMCIF Global Multi-Currency Input File

Global Multi-Currency Input File (GMCIF) Version 2.68 Global Multi-Currency Settlement File (GMCIF) Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose of Document ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Supporting Documentation............................................................................................................................. 4 Support Services .............................................................................................................................................. 4 File Processing ...................................................................................................................................... 5 File Delivery ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Processing Cycle .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Multiple Files ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Validation ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Development Guidelines ..................................................................................................................... -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

ZIMRA Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for Period 24 Dec 2020 To

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 24 DEC 2020 - 13 JAN 2021 ZWL CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATECURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 7.9981 0.1250 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 0.0497 20.1410 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 1.0092 0.9909 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 0.4819 2.0753 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 0.0162 61.7367 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 0.8994 1.1119 AUSTRIA EUR 0.0100 99.6612 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 0.9115 1.0972 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.0046 217.5176 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 0.1792 5.5819 BELGIUM EUR 0.0100 99.6612 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.0100 99.6612 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 0.1322 7.5356 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 0.0173 57.6680 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 0.0631 15.8604 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 4.7885 0.2088 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.0091 109.5983 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 11.0048 0.0909 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 23.8027 0.0420 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 0.1068 9.3633 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 0.0158 63.4921 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.0047 212.7090 CHINESE RENMINBI YUANCNY 0.0800 12.5000 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 1.9648 0.5090 CUBAN PESO CUP 0.3240 3.0863 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 0.0452 22.1111 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 PORTUGAL EUR 0.0100 99.6612 CZECH KORUNA CZK 0.2641 3.7860 QATARI RIYAL QAR 0.0445 22.4688 DANISH KRONER DKK 0.0746 13.4048 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 0.9287 1.0768 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 0.1916 5.2192 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 12.0004 0.0833 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 0.4792 2.0868 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 0.0459 21.8098 EURO EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 0.0163 61.2728 FINLAND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SPAIN EUR 0.0100 99.6612 FRANCE EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 0.1792 5.5819 GERMANY EUR 0.0100 99.6612 -

Zimra Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for the Period 08 to 14 July

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 08 TO 14 JULY 2021 USD BASE CURRENCY - USD DOLLAR CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 650.4178 0.0015 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 4.1598 0.2404 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 95.9150 0.0104 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 42.8000 0.0234 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 1.3329 0.7503 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 8.9490 0.1117 AUSTRIA EUR 0.8454 1.1829 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 63.9250 0.0156 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.3760 2.6596 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 14.3346 0.0698 BELGIUM EUR 0.8454 1.1829 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.8454 1.1829 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 10.9709 0.0912 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 1.4232 0.7027 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 5.1970 0.1924 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 410.9200 0.0024 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.7241 1.3810 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 900.0228 0.0011 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 1983.5620 0.0005 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 8.7064 0.1149 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 1.2459 0.8026 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.3845 2.6008 CHINESE RENMINBI YUAN CNY 6.4690 0.1546 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 158.3558 0.0063 CUBAN PESO CUP 24.0957 0.0415 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 3.8154 0.2621 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 PORTUGAL EUR 0.8454 1.1829 CZECH KORUNA CZK 21.6920 0.0461 QATARI RIYAL QAR 3.6400 0.2747 DANISH KRONER DKK 6.2866 0.1591 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 74.2305 0.0135 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 15.6900 0.0637 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 1001.5019 0.0010 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 43.9164 0.0228 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 3.7500 0.2667 EURO EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 1.3478 0.7419 FINLAND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SPAIN EUR 0.8454 1.1829 FRANCE EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 14.3346 0.0698 GERMANY -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

8 │ ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS Abbreviations and acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank AFD Agence Française de Développement BB Basic benefit BPJS Bandan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial [Social Insurance Administration Organization], Indonesia BRL Brazilian real BSM Bantuan Siswa Miskin [Cash Transfers for Poor Students], Indonesia BSP Benefício para Superação da Extrema Pobreza [Benefit to Overcome Extreme Poverty], Brazil BV Benefício Variável [Variable Benefits], Brazil BVJ Benefício Variável Jovem [Variable Youth Benefit], Brazil CCTs Conditional cash transfers DFID Department for International Development ECD Early childhood development EUR Euro FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FRDD Fuzzy regression discontinuity design GDP Gross domestic product GHS Ghanaian cedi ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights ICT Information and communication technology IDB Inter-American Development Bank IDR Indonesian rupiah ILO International Labour Organization INSS Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social [National Social Security Institute], Brazil IPEA Instituto de Pesquisa Economica Aplicada [Institute for applied economic research], Brazil ISSA International Social Security Association CAN SOCIAL PROTECTION BE AN ENGINE FOR INCLUSIVE GROWTH? © OECD 2019 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS │ 9 IV Instrumental variable IZA Institute of Labor Economics JHT Jaminan Hari Tua [Old Age Insurance], Indonesia JKK Jaminan Kecelakaan Kerja [Occupational Injury Benefit], Indonesia JKM Jaminan Kematian [Survivor Allowance], -

Ghana at a Glance

GHANA AT A GLANCE POPULATION: 27,499,924 (July 2017 est.) LANGUAGES: English; more than 50 tribal languages, including Asante, Ewe, Fante, Boron and Dagomba PREDOMINANT RELIGIONS: Christian, Islam, traditional TIME ZONE: Four hours ahead of Eastern Daylight Time (New York City) TELEPHONE CODES: 233, country code; 21, Accra city code Ghana, called West Africa’s Gold Coast during the colonial era, is better known for its lovely beaches, lively nightlife, good roads, COMPASSION IN GHANA variety of landscapes and friendly people than for dramatic Compassion’s ministry in Ghana began in 2004. Today, more scenery or wild animals. However, these assets make Ghana a than 52,000 children are served by more than 250 Compassion- safe and fascinating introduction to West Africa. assisted child development centers throughout the country. Compassion’s church-based child development centers are Although it was once a center of the slave trade, Ghana became places of hope for impoverished children in Ghana. Under the first modern African country to win its independence — the guidance of caring Christian adults, children’s pressing giving it a head start in nation-building. Ghana’s people are needs for nutrition and medical attention are met. Children well-educated, and it has good schools, a thriving journalistic also receive tutoring to help with their academics. Health and press and one of the highest economic growth rates on the hygiene lessons teach them to care for their own physical well- continent. Moreover, Ghana has managed not merely to retain a being, and positive social skills are modeled and encouraged. strong sense of national identity and pride but actually to boost its economy and infrastructure. -

Poverty & Equity Brief

Poverty & Equity Brief Sub-Saharan Africa Ghana April 2019 Ghana realized significant poverty reduction and reduced the poverty rate by half in line with the first Millennium Development Goal target with little increase in income inequality. Ghana's poverty rate at 2011 PPP $1.90 per person per day was 47.4 percent in 1991. In 2016, Ghana's poverty rate at $1.90 was down to 13.3 percent, lower than not only the mean poverty rate of Sub-Saharan Africa but also the mean poverty rate of middle-income countries. Ghana's largest fall in poverty was experienced from 1991 to 1998. Since then, poverty reduction has slowed down, and the growth elasticity of poverty has decreased remarkably. Spatial inequality widened, and poverty and vulnerability became more concentrated in the Northern three regions (Northern, Upper East, and Upper West) and the Volta region. The extreme poverty rate declined from 5.2 percent to a negligible share in Greater Accra between 2005 and 2016, while the extreme poverty rate fell from 76 percent to only 45.2 percent in Upper West region during the same period. The spatial inequities reflect both ecological conditions and disparities in service delivery. Agriculture remains the dominant employer in the three Northern regions, but the climate is not suitable for cocoa and other cash crops. The percentage of households using electricity increased from 45 percent to 81 percent between 2005 and 2016 in Ghana. However, only 49 and 59 percent of households had access to electricity in Upper East and Upper West regions, respectively, in 2016. -

Exchange Rate Behaviour in the West Africa Monetary Zone: a GARCH Approach

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Exchange Rate Behaviour in the West Africa Monetary Zone: A GARCH Approach Oshinloye, Micheal and Onanuga, Olaronke and Onanuga, Abayomi Olabisi Onabanjo University, University of South Africa, Olabisi Onabanjo University 4 January 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/83324/ MPRA Paper No. 83324, posted 20 Dec 2017 16:37 UTC Exchange Rate Behaviour in the West African Monetary Zone: A GARCH Approach Oshinloye Michael Olufemi B. Department of Accounting Banking and Finance, Olabisi Onabanjo University Ago-Iwoye, Ogun state, Nigeria. Onanuga Olaronke Toyin Doctoral student in Economics, School of Economic Sciences College of Economic and Management Sciences, University of South Africa (UNISA) Pretoria, South Africa. Onanuga Abayomi Toyin (Corresponding Author) Department of Accounting Banking and Finance, Olabisi Onabanjo University Ago-Iwoye, Ogun state, Nigeria. Tel: +234-803-351-9370 E-mail: [email protected] 1 Exchange Rate Behavior in the West African Monetary Zone –A GARCH Approach Abstract This study employs Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroscedasticity (GARCH) to explore the level of exchange rate volatility in West African Monetary Zone for the period 1980-2014. Our empirical findings reveal that the Gambian dalasi experiences the least volatile official exchange rate while the Liberia dollar is the most volatile in the Zone. There is need for government of Gambia and Nigeria to control overshooting dynamics experienced by dalasi and naira. All the countries should exercise monetary and fiscal measures on time to put their exchange rate volatility under check. Key words: Exchange rate Volatility, GARCH, West African Monetary Zone JEL Classification: C10, F02, F31 1.0 Introduction Exchange rates and their rates of change, in the course of time, are often as reported in the literature to be inconsistent with equilibrium. -

Economic and Sociocultural Aspects of Cowrie Currency of the Dagaaba of Northwestern Ghana Aspects EMMANUEL YIRIDOE University of Guelph, Canada

Nordic Journal of African Studies 4(2): 17-32 (1995) Economic and Sociocultural Aspects of Cowrie Currency of the Dagaaba of Northwestern Ghana Aspects EMMANUEL YIRIDOE University of Guelph, Canada ABSTRACT The cowrie currency, the dominant medium of exchange in Ghana before the introduction of the West African Pound and, later, the Cedi, is now merely a vestigial relic in virtually all of modern Ghana except among the Dagaaba. This paper provides an insider's perspective on the economic importance and on the unique role of the cowrie currency among the Dagaaba that explains its perpetual presence. Cultural uses create a derived demand for cowries. Government policies result in debasement of the cedi and, together with monetary characteristics of the cowrie, lead to competition between the cedi and the cowrie. INTRODUCTION In the history of monetary economics, various commodities have evolved as media of exchange because of their intrinsic characteristics and users' extrinsic beliefs. The traditional roles of the cowrie, a previously important medium of exchange, have faded away in virtually all of present day Ghana with the introduction of the national currency, the cedi. However, among the Dagaaba of Northwestern Ghana, cowries have been part of the people as far back as their history goes. Cowries are still used for both monetary and nonmonetary purposes. There have been very little (if any) documented studies on the history of the Dagaaba (Bodomo 1994: 40), and not any on the role of cowries among the Dagaaba. Johnson (1965: 37) notes that many studies around the world on cowrie currencies are generally examined as 'primitive money'. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S.