Stoically Sapphic: Gentlemanly Encryption and Disruptive Legibility in Adapting Anne Lister

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anne Lister's Use of and Contributions to British Romanticism

THE CLOSET ROMANTIC: ANNE LISTER’S USE OF AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO BRITISH ROMANTICISM ___________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department English Sam Houston State University ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts ___________ by Michelina Olivieri May, 2021 THE CLOSET ROMANTIC: ANNE LISTER’S USE OF AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO BRITISH ROMANTICISM by Michelina Olivieri ___________ APPROVED: Kandi Tayebi, PhD Committee Director Audrey Murfin, PhD Committee Member Evelyn Soto, PhD Committee Member Chien-Pin Li, PhD Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences DEDICATION For Jasmine, who never gave up on me, even when I did. We made it. iii ABSTRACT Olivieri, Michelina, The closet romantic: Anne Lister’s use of and contributions to British romanticism. Master of Arts (English), May, 2021, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. In this thesis, I explore Anne Lister as a Romantic writer. While much criticism has focused on Lister’s place in queer history, comparatively little has examined her writing itself. Thus, this thesis aims to place Lister’s writings within popular Romantic genres and in conversation with other Romantic writers. Chapter I is an introduction to Anne Lister and the scholarship that has surrounded her since the first collection of her diaries was published in the 1980s and establishes the arguments that will be made in each chapter. In Chapter II, I examine how Lister uses Romantic works and their writers to construct her own personal identity despite her lack of participation in either the written tradition or in the major social movements of the period during her lifetime. -

John Collins Production Designer

John Collins Production Designer Credits include: BRASSIC Director: Rob Quinn, George Kane Comedy Drama Series Producer: Mags Conway Featuring: Joseph Gilgun, Michelle Keegan, Damien Molony Production Co: Calamity Films / Sky1 FEEL GOOD Director: Ally Pankiw Drama Series Producer: Kelly McGolpin Featuring: Mae Martin, Charlotte Richie, Sophie Thompson Production Co: Objective Fiction / Netflix THE BAY Directors: Robert Quinn, Lee Haven-Jones Crime Thriller Series Producers: Phil Leach, Margaret Conway, Alex Lamb Featuring: Morven Christie, Matthew McNulty, Louis Greatrex Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / ITV GIRLFRIENDS Directors: Kay Mellor, Dominic Leclerc Drama Series Producer: Josh Dynevor Featuring: Miranda Richardson, Phyllis Logan, Zoe Wanamaker Production Co: Rollem Productions / ITV LOVE, LIES AND RECORDS Directors: Dominic Leclerc, Cilla Ware Drama Producer: Yvonne Francas Featuring: Ashley Jensen, Katarina Cas, Kenny Doughty Production Co: Rollem Productions / BBC One LAST TANGO IN HALIFAX Director: Juliet May Drama Series Producer: Karen Lewis Featuring: Sarah Lancashire, Nicola Walker, Derek Jacobi Production Co: Red Production Company / Sky Living PARANOID Directors: Kenny Glenaan, John Duffy Detective Drama Series Producer: Tom Sherry Featuring: Indira Varma, Robert Glennister, Dino Fetscher Production Co: Red Production Company / ITV SILENT WITNESS Directors: Stuart Svassand Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: Ceri Meryrick Featuring: Emilia Fox, Richard Lintern, David Caves Production Co: BBC One Creative Media Management -

Caroline Cornish Management

CAROLINE CORNISH MANAGEMENT 12 SHINFIELD STREET, LONDON W12 OHN Tel: 44 (0) 20 8743 7337 Mobile: 07725 555711 e-mail: [email protected] www.carolinecornish.co.uk MAGI VAUGHAN - HAIR & MAKE-UP DESIGNER BAFTA AWARD WINNER - 3 BAFTA NOMINATIONS 1 EMMY AWARD - 1 EMMY NOMINATION 2 MAKE-UP ARTISTS & HAIR STYLISTS GUILD AWARDS Make-Up application by AIR-BRUSH Special Make-Up Effects/Prosthetics Application and Making of Gelatine & Silicone Pieces Character and Period Makeup/Hair Work including Wigs and Hairpieces Countries Worked In: Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Holland, Hungary, Malta, Mallorca, Morocco, Romania, South Africa Languages Spoken: Fluent Welsh, Basic French and Spanish, Hungarian and Italian AVENUE 5 Prod Co: Jettison Productions/HBO Producers: Kevin Loader, Richard Daldry Directors: Armando Iannuci + TBC ALEX RIDER II Prod Co: Eleventh Hour Productions/Sony Producer: Richard Burrell Directors: TBC THE MALLORA FILES II Production Suspended due to Coronavirus 10x45min Drama Series Producer: Dominic Barlow Directors: Bryn Higgins, Rob Evans, Craig Pickles, Christina Ebohon-Green SUPPRESSION Prod Co: Snowdonia Feature Film Producers: Andrew Baird, Tom Warren Director: J Mackye Gruber CASTLE ROCK II Prod Co: Scope Productions Moroccan Unit Producer: Debbie Hayn-Cass. Director: Phil Abraham Drama Series Ep 202/204 THE MALLORCA FILES Prod Co: Cosmopolitan Pictures/Clerkenwell Films/BBC 10 x 45 min Drama Series Producer: Dominic Barlow Mallorca Director(s): Bryn Higgins, Charlie Palmer, Rob Evans, Gordon Anderson Featuring: Elen Rhys, Julian Looman RIVIERA II Prod Co: Archery Pictures/SKY 10pt Drama Series Producer: Sue Howells South of France Directors: Hans Herbots, Paul Walker, Destiny Ekaragha Featuring: Poppy Delevingne, Roxanne Duran, Jack Fox, Dimitri Leonidas, Lena Olin, Juliet Stephenson, Julia Stiles Registered Office: White Hart House, Silwood Road, Ascot SL5 0PY. -

Maria Kyriacou

MINUTES SEASON 8 1 3 THE EUROPEAN SERIES SUMMIT JULY FONTAINEBLEAU - FRANCE 2019 CREATION EDITORIAL TAKES POWER! This mantra, also a pillar of Série Series’ identity, steered Throughout the three days, we shone a light on people the exciting 8th edition which brought together 700 whose outlook and commitment we particularly European creators and decision-makers. connected with. Conversations and insight are the DNA of Série Series and this year we are proud to have During the three days, we invited attendees to question facilitated particularly rich conversations; to name but the idea of power. Both in front and behind the camera, one, Sally Wainwright’s masterclass where she spoke of power plays are omnipresent and yet are rarely her experience and her vision with a fellow heavyweight deciphered. Within an industry that is booming, areas in British television, Jed Mercurio. Throughout these of power multiply and collide. But deep down, what is Minutes, we hope to convey the essence of these at the heart of power today: is it the talent, the money, conversations, putting them into context and making the audience? Who is at the helm of series production: them available to all. the creators, the funders, the viewers? In these Minutes, through our speakers’ analyses and stories, we hope to For the first time, this year, we have also wanted to o er you some food for thought, if not an answer. broaden our horizons and o er a “white paper” as an opening to the reports, focusing on the theme of Creators, producers, broadcasters: this edition’s power, through the points of view that were expressed 120 speakers flew the flag for daring and innovative throughout the 8 editions and the changes that Série 3 European creativity and are aware of the need for the Series has welcomed. -

Graham Drover 1St Assistant Director

Graham Drover 1st Assistant Director Credits Include: YOU Directors: Robbie McKillop, Samira Radsi Dark Thriller Drama Series Producer: Derek Ritchie Featuring: tba Production Co: Kudos Film & TV / Sky Atlantic TIME Director: Lewis Arnold Crime Drama Producer: Simon Maloney Featuring: Sean Bean, Stephen Graham, Aneurin Barnard Production Co: BBC One DES Director: Lewis Arnold Drama Producer: David Meanti Featuring: David Tennant, Daniel Mays, Jason Watkins Production Co: New Pictures / ITV THE SMALL HAND Director: Justin Molotnikov Thriller Producer: Jane Steventon Featuring: Louise Lombard, Douglas Henshall, Neve McIntosh Production Co: Awesome Media & Entertainment / Channel 5 ELIZABETH IS MISSING Director: Aisling Walsh Drama Producer: Chrissy Skinns Featuring: Glenda Jackson, Helen Behan, Sophie Rundle Production Co: STV / BBC One BAFTA Nomination for Best Single Drama GUILT Director: Robbie McKillop Dark Crime Thriller Producer: Jules Hussey Featuring: Mark Bonnar, Jamie Sives, Sian Brooke Production Co: Happy Tramp North / Expectation / BBC One ROSE Director: Jennifer Sheridan Horror Producers: Sara Huxley, April Kelley, Matt Stokoe, Robert Taylor Featuring: Sophie Rundle, Matt Stokoe, Olive Grey Production Co: Mini Productions / The Development Partnership DARK MON£Y Director: Lewis Arnold Drama Producer: Erika Hossington Featuring: Rudi Dharmalingam, Rebecca Front, Jill Halfpenny Production Co: The Forge / BBC One Creative Media Management | 10 Spring Bridge Mews | London | W5 2AB t: +44 (0)20 3795 3777 e: [email protected] -

Mckinney Macartney Management Ltd

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd AMY ROBERTS - Costume Designer THE CROWN 3 Director: Ben Caron Producers: Michael Casey, Andrew Eaton, Martin Harrison Starring: Olivia Colman, Tobias Menzies and Helena Bonham Carter Left Bank Pictures / Netflix CLEAN BREAK Director: Lewis Arnold. Producer: Karen Lewis. Starring: Adam Fergus and Kelly Thornton. Sister Pictures. BABS Director: Dominic Leclerc. Producer: Jules Hussey. Starring: Jaime Winstone and Samantha Spiro. Red Planet Pictures / BBC. TENNISON Director: David Caffrey. Producer: Ronda Smith. Starring: Stefanie Martini, Sam Reid and Blake Harrison. Noho Film and Television / La Plante Global. SWALLOWS & AMAZONS Director: Philippa Lowthorpe. Producer: Nick Barton. Starring: Rafe Spall, Kelly Macdonald, Harry Enfield, Jessica Hynes and Andrew Scott. BBC Films. AN INSPECTOR CALLS Director: Aisling Walsh. Producer: Howard Ella. Starring: David Thewlis, Miranda Richardson and Sophie Rundle. BBC / Drama Republic. PARTNERS IN CRIME Director: Ed Hall. Producer: Georgina Lowe. Starring: Jessica Raine, David Walliams, Matthew Steer and Paul Brennen. Endor Productions / Acorn Productions. Gable House, 18 –24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 AMY ROBERTS Contd … 2 CILLA Director: Paul Whittington. Producer: Kwadjo Dajan. Starring: Sheridan Smith, Aneurin Barnard, Ed Stoppard and Melanie Hill. ITV. RTS CRAFT & DESIGN AWARD 2015 – BEST COSTUME DESIGN BAFTA Nomination 2015 – Best Costume Design JAMAICA INN Director: Philippa Lowthorpe Producer: David M. Thompson and Dan Winch. Starring: Jessica Brown Findlay, Shirley Henderson and Matthew McNulty. Origin Pictures. THE TUNNEL Director: Dominik Moll. Producer: Ruth Kenley-Letts. Starring: Stephen Dillane and Clemence Poesy. Kudos. CALL THE MIDWIFE (Series 2) Director: Philippa Lowthorpe. -

Scott & Bailey 2 Wylie Interviews

Written by Sally Wainwright 2 PRODUCTION NOTES Introduction .........................................................................................Page 3 Regular characters .............................................................................Page 4 Interview with writer and co-creator Sally Wainwright ...................Page 5 Interview with co-creator Diane Taylor .............................................Page 8 Suranne Jones is D.C. Rachel Bailey ................................................Page 11 Lesley Sharp is D.C. Janet Scott .......................................................Page 14 Amelia Bullmore is D.C.I. Gill Murray ................................................Page 17 Nicholas Gleaves is D.S. Andy Roper ...............................................Page 20 Sean Maguire is P.C. Sean McCartney ..............................................Page 23 Lisa Riley is Nadia Hicks ....................................................................Page 26 Kevin Doyle is Geoff Hastings ...........................................................Page 28 3 INTRODUCTION Suranne Jones and Lesley Sharp resume their partnership in eight new compelling episodes of the northern-based crime drama Scott & Bailey. Acclaimed writer and co-creator Sally Wainwright has written the second series after once again joining forces with Consultancy Producer Diane Taylor, a retired Detective from Greater Manchester Police. Their unique partnership allows viewers and authentic look at the realities and responsibilities of working within -

Anne Lister Lesson Plan

ANNE LISTER Pioneering British Lesbian Landowner and Businesswoman (1791-1840) In an era when women had virtually no voice or power, Anne Lister of Yorkshire, England defied the odds to become what some call the first modern lesbian for her open lifestyle and self-knowledge. Despite being taunted by fellow Halifax residents, who referred to her as “Gentleman Jack,” Lister flouted convention by dressing in black men’s attire and talking part in typically male activities, such as riding and shooting. In 1830, she became the first woman to ascend Mount Perdu in the Pyrenees and several years later completed the official ascent of the Vignelmale, the highest point in the mountain range. Though she conventionally shied away identification with “Sapphists,” she declared in her voluminous 4-million-word diary “I love and in love the fairer sex and thus beloved by them I turn, my heart revolts from any love but theirs.” Obscuring the nature of her affections, the diary incorporated a special code combining Algebra and Ancient Greek to detail her intimate relationships as well as her day to day life as a wealthy “rural gentlemen”—including the operation of her family estate, her business interests, and social and national events. It has also come to be highly prized by historians who value its unique perspective on the experience of lesbians in early 19th-century England. Lister’s first great romance, with Mariana Lawton, ended when Lawton refused to leave her husband. In 1832, she met heiress Anne Walker and the two were “married” in a private declaration of their life-commitment. -

Happy Valley: Compassion, Evil and Exploitation in an Ordinary ‘Trouble Town’

Piper, H. (2017). Happy Valley: Compassion, Evil and Exploitation in an Ordinary ‘Trouble Town’. In D. Forrest, & B. Johnson (Eds.), Social Class and Television Drama in Contemporary Britain (pp. 181-200). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-55506-9_13 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1057/978-1-137-55506-9_13 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Palgrave Macmilland at https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-55506-9_13 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ 219 NB. PRE-PUBLICATION Final accepted version of chapter for inclusion in: Forrest, D & Johnson, B (eds) Social Class and Television Drama in Contemporary Britain, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. CHAPTER 13 Happy Valley: Compassion, evil and exploitation in an ordinary ‘trouble town’ Helen Piper There can be few topics more vexed and contradictory than that of class, not least for the scholar of contemporary television. After many years in the wilderness when, so the historian David Cannadine punned, it was very much a matter of ‘class dismissed’ from national political and historical discourse (1998: 8), it is now finally back on the agenda, although variously configured in different disciplines. -

Class and Gender Identify in the Film Transpositions of Emily Brontë's

Seijo Richart 1 Appendix II: Transpositions of Wuthering Heights to other Media 1. Television 1.1. TV - films 1948 Wuthering Heights. Adapt. John Davidson (from his stage play). BBC TV. 1948 Wuthering Heights. Kraft Television Theatre, NBC (USA). TV broadcast of a performance of Rudolph Carter’s theatre transposition. Only the first half of the novel. 1950 “Wuthering Heights”. Westinghouse's Studio One. Perf. Charlton Heston. USA. 1953 Wuthering Heights. Perf. Richard Todd and Yvonne Mitchell. BBC TV (UK). Script by Nigel Kneale, based on Rudolph Carter’s theatre transposition. 1958 Wuthering Heights. Perf. Richard Burton and Rosemary Harris. UK 1962 Wuthering Heights. Perf. Keith Mitchell and Claire Bloom. BBC TV (UK). Script by Nigel Kneale, based on Rudolph Carter’s theatre transposition. 1998 Wuthering Heights. Dir. David Skynner. Perf. Robert Kavanah, Orla Brady. Script by Neil McKay. London Weekend Television. 2003 Wuthering Heights. Dir. Suri Kirshnamma. Writ. Max Enscoe. Perf. Erika Christensen, Mike Vogel. MTV Films. 1.2. TV Series 1956 Cime tempestose. Dir. Mario Landi. Italy. 1963. Cumbres Borrascosas. Dir & Prod. Daniel Camino. Perú. 1964 Cumbres Borrascosas. Dir. Manuel Calvo. Prod. Ernesto Alonso (Eduardo/ Edgar in Abismos). Forty-five episodes. México. 1967 Wuthering Heights. Dir. Peter Sasdy. Adapt. Hugh Leonard. Perf. Ian McShane, Angela Scoular. Four parts serial. BBC TV (UK). 1967 O Morro dos Ventos Uivantes. Adap. Lauro César Muniz. TV Excelsior (Brasil). 1968 Les Hauts de Hurlevent. Dir. Jean-Paul Carrère. France. Two parts. Early 1970s A serialised version in the Egyptian television. 1973 Vendaval. Adapt. Ody Fraga. Perf. Joana Fomm. TV Record (Brasil). 1976 Cumbres Borrascosas. -

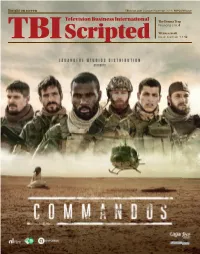

Scriptedpofc Octnov19.Indd

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | October/November 2019 | MIPCOM Issue Television Business International e Drama Trap Financing a hit 4 Writers revolt TBI Scripted Inside Kontrakt '18 12 ScriptedpOFC OctNov19.indd 1 03/10/2019 00:36 LAGARDERE_COMMANDO_TBI_COVER_def.indd 1 19/09/2019 15:49 BASED ON THE AWARD-WINNING NOVELS ON THE AWARD-WINNING BASED A NEW ORIGINAL SERIES p02-03 ITV Noughts & Crosses OctNov19.indd 2 02/10/2019 15:18 ITV0272_NOXO_TBIMipMain_IFCDPS_SubAW.indd All Pages 02/10/2019 14:08 BASED ON THE AWARD-WINNING NOVELS ON THE AWARD-WINNING BASED A NEW ORIGINAL SERIES p02-03 ITV Noughts & Crosses OctNov19.indd 3 02/10/2019 15:18 ITV0272_NOXO_TBIMipMain_IFCDPS_SubAW.indd All Pages 02/10/2019 14:08 Genre: Drama | Duration: 6x60' VISIT US AT MIPCOM, STAND R8.C9, RIVIERA 8 Catalogue: www.keshetinternational.com Contact us: [email protected] @KeshetIntl | KeshetInternational | @KeshetInternational ScriptedpXX Keshet Keeler OctNov19.indd 1 24/09/2019 12:49 TBI Scripted | This Issue Contents October/November 2019 4. Inside the multi-million dollar drama trap Contact us High-end scripted product has never been more lucrative but it also carries increasing risk, so how can producers and distributors navigate these challenging times? Editor Manori Ravindran [email protected] 8. Duking it out with global drama Direct line +44 (0) 20 3377 3832 TBI takes a trip to Ireland to find out about A+E Networks International’s uniquely Twitter @manori_r funded drama Miss Scarlet And The Duke. Managing editor Richard Middleton 12. When writers revolt [email protected] Creative talent might be in demand but writers from LA to Berlin feel they aren’t Direct line +44 (0) 20 7017 7184 being given the recognition they deserve. -

Gentleman Jack

! ! ! ! ! GENTLEMAN JACK Episode 8 Written and created by Sally Wainwright 7th November 2018! ! ! ! ! STRICTLY PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL © Lookout Point Limited, 2019. All rights reserved. No part of this document or its contents may be disclosed, distributed or used in, for or by any means (including photocopying and recording), stored in a retrieval system, disseminated or incorporated into any other work without the express written permission of Lookout Point Limited, the copyright owner. Any unauthorised use is strictly prohibited and will be prosecuted in courts of pertinent jurisdiction. Receipt of this script does not constitute an offer of any sort. ! ! ! GENTLEMAN JACK. Sally Wainwright. EPISODE 8. 7.11.18. 1. 1 EXT. THE ROAD TO GOTTINGEN, GERMANY. DAY 55. 15:00 (AUTUMN 1 1832) Idyllic fairy-tale German countryside. ANNE’s carriage (loaded with luggage) travels along a country road. EUGÉNIE and THOMAS sit outside at the back, not speaking. 1A INT. ANNE’S CARRIAGE, ROAD TO GOTTINGEN. DAY 55. CONTINUOUS1A. Inside the carriage, we find ANNE LISTER, gazing diagonally opposite at a young woman. ANNE LISTER (voice over) My dear Aunt. Providence has once again bent her gently smiling beams my way... 2 INT. DRAWING ROOM, SHIBDEN. DAY 56. 15:55 (AUTUMN 1832) 2 We find AUNT ANNE LISTER (with her poorly leg raised on a stool in front of the fire) devouring ANNE’s breathlessly pacey letter. (JEREMY and ARGUS are asleep). ANNE LISTER (v.o. immediately continuous from above) When I visited Madame de Bourke in the Rue Faubourg Saint Honoré and told her of my indecision whether to go north or south, she wasted no time in begging me to accompany her niece - a Miss Sophie Ferrall - to Copenhagen.