The Superiority of Economists†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HANNAH C. WAIGHT 107 Wallace Hall [email protected] Princeton, NJ 08540

HANNAH C. WAIGHT 107 Wallace Hall [email protected] Princeton, NJ 08540 EDUCATION Princeton University 2021 Ph.D., Sociology (expected) 2017 M.A., Sociology Harvard University 2014 M.A., Regional Studies: East Asia 2010 B.A., East Asian Studies RESEARCH INTERESTS sociology of media and information; contemporary China; computational social science; history of social thought PUBLICATIONS Under Review “Decline of the Sociological Imagination? Social Change and Perceptions of Economic Polarization in the United States, 1966-2009” (with Adam Goldstein) Using forty years of public opinion polls, we explain historical trends in perceptions of distributional inequality, a trend which tracks inversely with the underlying phenomena. “John Dewey and the Pragmatist Revival in American Sociology” This manuscript analyzes John Dewey’s writings on the social sciences and contrasts Dewey’s perspective with contemporary uses of Dewey’s ideas in American sociology. Manuscripts in Preparation “Identifying Propaganda in China” (with Molly Roberts, Brandon Stewart, and Yin Yuan) This computational project employs a novel data set of Chinese newspapers from 2012 to 2020 to examine the prevalence and content of government media control in China. Works in Progress “Attention and Propaganda Chains in Contemporary China” (with Eliot Chen) This survey experiment combines a traditional vignette design with a text-as-treatment framework to examine the effects of source labels on respondent attention to state propaganda in China. Other Writing “Moral Economies -

The Social and Political Views of American Professors

THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL VIEWS OF AMERICAN PROFESSORS Neil Gross Harvard University [email protected] Solon Simmons George Mason University [email protected] Working Paper, September 24, 2007 Comments and suggestions for revision welcome In 1955, Columbia University sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld received a grant from The Ford Foundation’s newly established Fund for the Republic – chaired by former University of Chicago President Robert M. Hutchins – to study how American social scientists were faring in the era of McCarthyism. A pioneering figure in the use of social surveys, Lazarsfeld employed interviewers from the National Opinion Research Center and Elmo Roper and Associates to speak with 2451 social scientists at 182 American colleges and universities. A significant number of those contacted reported feeling that their intellectual freedom was being jeopardized in the current political climate (Lazarsfeld and Thielens 1958). In the course of his research, Lazarsfeld also asked his respondents about their political views. Analyzing the survey data on this score with Wagner Thielens in their 1958 book, The Academic Mind, Lazarsfeld observed that liberalism and Democratic Party affiliation were much more common among social scientists than within the general population of the United States, and that social scientists at research universities were more liberal than their peers at less prestigious institutions. Although The Academic Mind was published too late to be of any help in the fight against McCarthy (Garfinkel 1987), it opened up a new and exciting area of sociological research: study of the political views of academicians. Sociologists of intellectual life, building on the contributions of Karl Marx, Max Weber, Karl Mannheim, and others, had 1 long been interested in the political sympathies of intellectuals (see Kurzman and Owens 2002), but most previous work on the topic had been historical in nature and made sweeping generalizations on the basis of a limited number of cases. -

Neil Gross Will Edit Perspectives Theory Section Activities At

Section News Newsletter Features •Theory Section Mini-Conference •Critical Discourse Analysis •Newsletter Editor Change •Post-Structurationist Potential •Election Results •Theory Development THE ASA July 2003r THEORY SECTION NEWSLETTER Perspectives VOLUME 26, NUMBER 3r Section Officers Theory Section Activities at the CHAIR Atlanta Meetings Linda D. Molm Linda D. Molm, University of Arizona CHAIR-ELECT he 2003 Annual Meetings of the American Sociological Association will take Michèle Lamont place on August 16-19 in Atlanta, Georgia. Monday, August 18 is Theory PAST CHAIR TSection Day. Most Section activities are scheduled on that day, with one session — the open submission paper session — scheduled the following morning. Gary Alan Fine All Section activities will be held at the Atlanta Hilton. Below is the full schedule of SECRETARY-TREASURER sessions and other Section activities. Please plan to attend as many of these events as possible! Patricia Madoo Lengermann COUNCIL Monday, August 18, Theory Section Day: Kevin Anderson 8:30-10:15 8:30 Theory Section Refereed Roundtables and Council Meeting (1 hr.) 9:30 Theory Section Business Meeting Robert J. Antonio Mathieu Deflem 10:30-12:15 Theory Section Mini-conference. “The Value of Theory: Classical Edward J. Lawler Theory” Cecilia L. Ridgeway See ATLANTA on page 6 Robin Stryker Editorial Change: SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY EDITOR Neil Gross Will Edit Perspectives Jonathan Turner J. David Knottnerus & Jean Van Delinder, Oklahoma State University PERSPECTIVES EDITORS his summer’s publication of Perspectives will be the final issue managed by the J. David Knottnerus & current editors. We would like to thank the ASA Theory Section for the op- Jean Van Delinder Tportunity to serve in this role for the last three years. -

Cancel Culture’ Stifling Academic Freedom and Intellectual Debate in Political Science? Faculty Research Working Paper Series

Closed Minds? Is a ‘Cancel Culture’ Stifling Academic Freedom and Intellectual Debate in Political Science? Faculty Research Working Paper Series Pippa Norris Harvard Kennedy School August 2020 RWP20-025 Visit the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series at: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/research-insights/publications?f%5B0%5D=publication_types%3A121 The views expressed in the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. Faculty Research Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. www.hks.harvard.edu Closed minds? Is a ‘cancel culture’ stifling academic freedom and intellectual debate in political science? Pippa Norris [email protected] Synopsis: Recent years have seen extensive debate in popular commentary about a pervasive ‘cancel culture’ thought to be taking over college campuses. A progressive orthodoxy, it is argued, has silenced conservative voices and diverse perspectives. This development, it is claimed, has ostracized contrarians, limited academic freedom, strengthened conformism, and eviscerated robust intellectual debate. But does systematic empirical evidence support these claims? After reviewing the arguments, Part II of this study outline several propositions arising from the cancel culture thesis and describes the sources of empirical survey evidence and measures used to test these claims within the discipline of political science. Data is derived from a new global survey, the World of Political Science, 2019, with 2,446 responses collected from scholars studying or working in 102 countries. -

The Politics of Knowledge: a Sociological Introduction to Science and Technology Studies

Sociology 476: The Politics of Knowledge: A Sociological Introduction to Science and Technology Studies Spring 2016 Mondays, 10:00-12:50 pm, in Allison 1021 *First course meeting on Tuesday, March 29* Professor Steven Epstein Department of Sociology Northwestern University Contact info: Office phone: 847-491-5536 E-mail: [email protected] Web page: http://www.sociology.northwestern.edu/faculty/StevenEpstein.html Drop-in office hours this quarter: Mondays, 2:00-3:30, in University Hall 020 (basement level) A copy of this syllabus can be found on the Canvas site for the course. Soc 476 Syllabus – Politics of Knowledge (Epstein, Spring 2016) – Page 2 Summary: This course is motivated by the assumption that questions of knowledge and technology have become central to the political and cultural organization of modern societies. The fundamental goal of the course is to develop tools to understand both the social organization of science and the technoscientific dimensions of social life. Although much of the actual course content concerns science and technology, the theoretical and analytical frameworks developed in this course are intended to apply to any domain involving knowledge, expertise, or technical tools. By examining the social, cultural, political and material dimensions of knowledge production, the course provides a broad introduction to sociological perspectives within Science & Technology Studies (STS). While being sensitive to the interdisciplinary character of STS, we will emphasize the following questions: • What have -

1/3 CURRICULUM VITAE Neil Gross Department of Sociology University

CURRICULUM VITAE Neil Gross Department of Sociology University of Southern California Los Angeles CA 90089-2539 (213) 821-2331 (phone) (213) 740-3535 (fax) [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002. M.S., Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1996. B.A., Legal Studies, University of California-Berkeley, 1992. POSITIONS HELD Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Southern California, 2002- Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Williams College, 2001-2002 FELLOWSHIPS AND ACADEMIC HONORS Teaching Award for a Lecturer, Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2000. University of Wisconsin Dissertation Fellowship, 1999-2000. Leo P. Chall Dissertation Fellowship, International Sociological Association, 1999. Phi Beta Kappa, High Distinction in General Scholarship and Highest Departmental Honors (Legal Studies), University of California-Berkeley, 1992. ARTICLES/CHAPTERS Neil Gross and Solon Simmons (forthcoming, 2002). “Intimacy as a Double Edged Phenomenon? An Empirical Test of Giddens.” Social Forces. Neil Gross (forthcoming, 2002). “Richard Rorty’s Pragmatism: A Sociological Account.” Theory and Society. Charles Camic and Neil Gross (2002). “Alvin Gouldner and the Sociology of Ideas: Lessons From Enter Plato.” The Sociological Quarterly 43:97-110. 1/3 Neil Gross (2002). “Becoming a Pragmatist Philosopher: Status, Self-Concept, and Intellectual Choice.” American Sociological Review 67:52-76. Charles Camic and Neil Gross (2001). “The New Sociology of Ideas.” Pp. 236-49 The Blackwell Companion to Sociology, J. Blau, ed. Cambridge: Blackwell. Charles Camic and Neil Gross (1998). “Contemporary Developments in Sociological Theory: Current Projects and Conditions of Possibility.” Annual Review of Sociology 24:453-76. Neil Gross (1997). “Durkheim’s Pragmatism Lectures: A Contextual Interpretation.” Sociological Theory 15:126-49. -

December 2018 Charles Camic Department of Sociology

December 2018 Charles Camic Department of Sociology Northwestern University 1810 Chicago Avenue Evanston, Illinois 60208 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Pittsburgh B.A. (summa cum laude), 1973 (major: sociology) University of Chicago M.A., Sociology, 1975 University of Chicago Ph.D., Sociology, 1979 AREAS OF RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTEREST Sociology of ideas; sociology of science; sociology of intellectuals; classical and contemporary sociological theory; history of the social sciences; American and European intellectual history; historical sociology CURRENT POSITION Lorraine H. Morton Professor of Sociology, Northwestern University, 2016- (Formerly titled John Evans Professor of Sociology, 2006-2016) Affiliate, Science in Human Culture Program, 2007- PREVIOUS POSITIONS Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1979-84 Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1984-88 Professor of Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1988-2006 (Associate Department Chair, 1988-91) Martindale-Bascom Professor of Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1999-2006 Visiting Professor of Sociology, Northwestern University, 2005-06 HONORS & AWARDS Recipient, “Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award,” American Sociological Association, History of Sociology Section, 2011. Stanley Kelley Jr. Visiting Professor for Distinguished Teaching, Princeton University, 2010-11 Fellowship, National Humanities Institute, 2010-11 (award declined) Fellowship, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, -

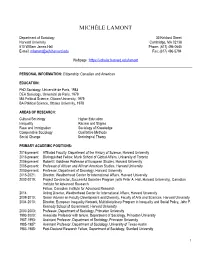

Michèle Lamont

MICHÈLE LAMONT Department of Sociology 33 Kirkland Street Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 510 William James Hall Phone: (617) 496-0645 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (617) 496-5794 Webpage : https://scholar.harvard.edu/lamont PERSONAL INFORMATION: Citizenship: Canadian and American EDUCATION: PhD Sociology, Université de Paris, 1983 DEA Sociology, Université de Paris, 1979 MA Political Science, Ottawa University, 1979 BA Political Science, Ottawa University, 1978 AREAS OF RESEARCH: Cultural Sociology Higher Education Inequality Racism and Stigma Race and Immigration Sociology of Knowledge Comparative Sociology Qualitative Methods Social Change Sociological Theory PRIMARY ACADEMIC POSITIONS: 2016-present: Affiliated Faculty, Department of the History of Science, Harvard University 2016-present: Distinguished Fellow, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto 2006-present: Robert I. Goldman Professor of European Studies, Harvard University 2005-present: Professor of African and African American Studies, Harvard University 2003-present: Professor, Department of Sociology, Harvard University 2015-2021: Director, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University 2002-2019: Project Co-director, Successful Societies Program (with Peter A. Hall, Harvard University), Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Fellow, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research 2014: Acting Director, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University 2009-2010: Senior Advisor on Faculty Development and Diversity, Faculty -

The Practice of International Law: a Theoretical Analysis

Jens Meierhenrich The practice of international law: a theoretical analysis Article (Published version) (Refereed) Original citation: Meierhenrich, Jens (2013) The practice of international law: a theoretical analysis. Law & Contemporary Problems, 76 (3-4). pp. 1-83. ISSN 0023-9186 © 2014 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/56321/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2014 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. 1 MEIRHENRICH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/19/2014 11:29 AM THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW: A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS JENS MEIERHENRICH* The tragedy of the world is that those who are imaginative have but slight experience, and those who are experienced have feeble imaginations. Fools act on imagination 1 without knowledge, and pedants act on knowledge without imagination. Alfred North Whitehead Out of the conjunction of activities and men around the law-jobs there arise the crafts of law, and so the craftsmen. Advocacy, counseling, judging, law-making, administering—these are the major grouping of the law-crafts. At the present juncture, the fresh study of these crafts and of the manner of their best doing is one of 2 the major needs of jurisprudence. -

September/October 2015

Volume 43 • Number 6 • September/October 2015 Meet the 2016 ASA President: Ruth Milkman Sarah Jaffe, Fellow, The Nation Institute It was Milkman’s commitment to works in the academy with a real public sociology, to making social world outlook,” says Dan Rounds, inside or Ruth Milkman, being a soci- change and calling out injustice a former student of Milkman’s at ologist is about doing F through rigorous academic UCLA who is now Deputy Director research that speaks to work that inspired Kristen of Legislation, Policy, and Research W.J. Wilson Gives Kluge the issues of the day. That 3 Schilt, now Associate at the California Workforce Lecture mindset has led her to Professor of Sociology at Investment Board. Milkman, he crisscross the country, from Wilson discussed the ways the University of Chicago. notes, encourages students to get the East Coast to California race and class influence Schilt studied under involved, an outlook that served and back again, to dig Americans’ opportunities. Milkman at the University him well in academia as well as in into historical archives to of California-Los Angeles the public policy position he now uncover the struggles of 2017 Theme and Call for (UCLA), and noted that for holds. From Milkman, he says, women workers during the Ruth Milkman 4 many people, the tension he learned that “Objectivity is not Suggestions Great Depression, to hang between wanting to change the about having no opinion, it means President Michèle Lamont out in factories with autoworkers world and wanting to be a com- that you form your opinions based has chosen the theme trying to save an industry being mitted scholar can be difficult to on solid evidence. -

Sociology Newsletter 5.04

Inside: Lamont on theoretical cultures (p. 1) • Statement by new Sociological Theory editors (p. 1) • J. Turner replies to Lamont (p. 2) • Harrison on teaching theory to undergraduates (p. 3) • Fourcade-Gourinchas on being a French-born sociologist (p. 4) • Four essays on the role of theory in law and society scholarship (starting on p. 5) • Listing of ASA theory sessions (p. 28) PerspectivesNewsletter of the ASA Theory Section volume 27, number 2, April 2004 Section Officers Theoretical Cultures in the Social Sciences Chair and the Humanities Michèle Lamont (Harvard University) Michèle Lamont, Harvard University Chair-Elect Murray Webster (University of North Carolina-Charlotte) In “Styles of Scientifi c Reasoning,” Ian Hacking discusses the historical formation of styles of argumentation that determine what is possible to Past Chair Linda Molm (University of Arizona) believe, based on specifi c conventions concerning arguments and reasons. He incites us to examine styles of reasoning in the social sciences and the Secretary-Treasurer humanities, that is, the theoretical cultures and their preferred modes of Patricia Lengermann (George Washington University) verifi cation and evaluation that prevail in these clusters of discipline. Thus, “Theoretical Cultures in the Social Sciences and the Humanities” will be the Council theme of the 2004 Theory Mini-Conference. I have asked Julia Adam and Kevin Anderson (Purdue University) Mathieu Defl em (University of South Neil Gross to join me in organizing three panels: 1) Theoretical Cultures Carolina) Across the Disciplines (with Don Brenneis, Judith Butler, Hazel Marcus, Uta Gerhardt (University of Heidelberg) and Richard Rorty); 2) Theoretical Cultures within Sociology (with Michael J. -

Futures Past

Futures Past. Economic Forecasting in the 20th and 21st Century LITERATUR — KULTUR — ÖKONOMIE LITERATURE — CULTURE — ECONOMY Herausgegeben von / Edited by Christine Künzel, Axel Haunschild, Birger P. Priddat, Thomas Rommel, Franziska Schößler und / and Yvette Sánchez VOLUME 5 Wissenschaftlicher Beirat / Editorial Board: Dr. phil. Georgiana Banita, Bamberg Dr. Bernd Blaschke, Bern Prof. Dr. Elena Esposito, Bielefeld / Bologna Univ.-Doz. Dr. Nadja Gernalzick, Mainz / Wien Prof. Dr. Anton Kirchhofer, Oldenburg Prof. Dr. Stefan Neuhaus, Koblenz Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Wolfgang Reinhard, Freiburg i.Br. Prof. Dr. Peter Seele, Lugano Prof. Dr. Urs Stäheli, Hamburg Zu Qualitätssicherung und Peer Review Notes on the quality assurance and peer der vorliegenden Publikation review of this publication Die Qualität der in dieser Reihe Prior to publication, the quality of the erscheinenden Arbeiten wird vor der work published in this series is double Publikation durch einen externen, von der blind reviewed by an external referee Herausgeberschaft benannten Gutachter appointed by the editorship. The im Double Blind Verfahren geprüft. Dabei referee is not aware of the author's ist der Autor der Arbeit dem Gutachter name when performing the review; während der Prüfung namentlich nicht the referee's name is not disclosed. bekannt; der Gutachter bleibt anonym. LITERATUR — KULTUR — ÖKONOMIE Ulrich Fritsche / Roman Köster / Laetitia Lenel (eds.) LITERATURE — CULTURE — ECONOMY Herausgegeben von / Edited by Christine Künzel, Axel Haunschild, Birger P. Priddat, Thomas Rommel, Franziska Schößler und / and Yvette Sánchez VOLUME 5 Futures Past. Economic Forecasting Wissenschaftlicher Beirat / Editorial Board: th st in the 20 and 21 Century Dr. phil. Georgiana Banita, Bamberg Dr. Bernd Blaschke, Bern Prof.