Why Rex Trueform Decided to Remain in Cape Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cape Town

Town The copyright of this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derivedCape from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of theof source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. University An investigation into the geographical trends in the sectoral composition of the Cape Town economy By Netshikulwe Azwihangwisi NTSAZW002 Supervisor Professor Owen Crankshaw Town A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MastersCape of Social Science in Sociology in the DepartmentOf of Sociology Faculty of the Humanities University University of Cape Town March 2010 Plagiarism Declaration This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotes from people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature Azwihangwisi Netshikulwe September 2009 Town Cape Of University I Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the financial contributions made by the following institutions towards my study: the National Research Foundation (NRF), the Harry Crossley Foundation, the KW Johnstone Research Scholarship and UCT Scholarship. To my supervisor, Professor Owen Crankshaw, your indefinite support and guidance have been a major determinant in my completing this degree. Thank you for assisting me throughout this journey and particularly in the theoretical component and for continuously providing me with data relevant to my study. Your support in my study has been immense and incalculable. I would also like to thank the City of Cape Town staff who provided me with the necessary data to conduct my research. -

2011 Census Suburb Woodstock July 2013

City of Cape Town – 2011 Census Suburb Woodstock July 2013 Compiled by Strategic Development Information and GIS Department (SDI&GIS), City of Cape Town 2011 Census data supplied by Statistics South Africa (Based on information available at the time of compilation as released by Statistics South Africa) The 2011 Census suburbs (190) have been created by SDI&GIS grouping the 2011 Census sub-places using GIS and December 2011 aerial photography. A sub-place is defined by Statistics South Africa “is the second (lowest) level of the place name category, namely a suburb, section or zone of an (apartheid) township, smallholdings, village, sub- village, ward or informal settlement.” Suburb Overview, Demographic Profile, Economic Profile, Dwelling Profile, Household Services Profile 2011 Census Suburb Description 2011 Census suburb Woodstock includes the following sub-places: University Estate, Walmer Estate, Woodstock. 1 Data Notes: The following databases from Statistics South Africa (SSA) software were used to extract the data for the profiles: Demographic Profile – Descriptive and Education databases Economic Profile – Labour Force and Head of Household databases Dwelling Profile – Dwellings database Household Services Profile – Household Services database In some Census suburbs there may be no data for households, or a very low number, as the Census suburb has population mainly living in collective living quarters (e.g. hotels, hostels, students’ residences, hospitals, prisons and other institutions) or is an industrial or commercial area. In these instances the number of households is not applicable. All tables have the data included, even if at times they are “0”, for completeness. The tables relating to population, age and labour force indicators would include the population living in these collective living quarters. -

In the Land Claims Court of South Africa

IN THE LAND CLAIMS COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA Heard at CAPE TOWN on 23-24 April, 26-27 July 2001 CASE NUMBER: LCC 13/00 2-3 August, 6-7 August, 17 September, 10-11 October 2001, 30 November, 3 December, 7 December 2001, 23-25 April and 19 July 2002. before Meer AJ and Murphy (assessor) Decided on: 01 October 2002 In the case of: IQBAL KAZI ALLIE NO First claimant ABDUL RAZAK MAHATEY NO Second claimant and THE DEPARTMENT OF LAND AFFAIRS First respondent PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION WESTERN CAPE: Second respondent DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING, LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND HOUSING ZUBEIDA ABRAMS Third respondent REGIONAL LAND CLAIMS COMMISSIONER, WESTERN CAPE Fourth respondent JUDGMENT MEER AJ: [1] A claim for restitution of a right in land in terms of the Restitution of Land Rights Act,1 (“the Restitution Act”) was lodged by Mr B A M Mahatey, an Indian gentleman and a pensioner of about seventy-eight years. The claim is in respect of Erf 12377, Cape Town, at Woodstock, 1 Act 22 of 1994, as amended. 2 also known as 3 Lever Street, Woodstock (“the subject property”).2 Mr Mahatey claimed that he was dispossessed of a right in land when the area of Woodstock was declared “Coloured” in terms of the Group Areas Act,3 and he was forced to sell the property to the Community Development Board (“the Board”) in December 1979 for a sum which did not constitute just and equitable compensation as contemplated in the Restitution Act.4 [2] Section 2 of the Restitution Act deals with entitlement to restitution and sets out the prerequisites for restitution as follows: “(1) A -

Shame and Respectability

SHAME AND RESPECTABILITY: A NARRATIVE INQUIRY INTO CAPE TOWN’S ‘COLOURED’ FAMILIES THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHS, CULTURAL PRACTICES AND ORAL HISTORIES (C. 1950 TO 2016) By Nadia Kamies (17405361) Submitted to the University of Pretoria in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Department of Historical and Heritage Studies Date of submission: 31 August 2018 Supervisor: Dr Siona O’Connell, University of Pretoria DECLARATION I, Nadia Kamies, hereby declare that the work on which this thesis is based is my original work (except where acknowledgements indicate otherwise) and that neither the whole work nor any part of it has been, is being, or is to be submitted for another degree in this or any other university. I authorise the University of Pretoria to reproduce, for the purpose of research, either the whole or any portion of the contents in any manner whatsoever. Signature: Date: MY GRANDMOTHER’S DREAM CATCHERS Mama made these doilies for me, my mother says, as green and blue tightly crocheted works of art fall softly out of the plastic packet she’s kept them in. I see my grandmother sitting in her chair, grey hair escaping from under a white cotton scarf wrapped around her head; her fingers hold the thin steel hook wrapping cotton thread in elaborate patterns, making poor man’s lace, creating circles in the air to catch bad dreams. Her hands are never idle, weaving and spinning a livelihood to keep her family together, her work good enough for even white people, my father says, the patterns out of a secret book in her head dipped in starch and ironed to attention. -

Forms of Regeneration in Woodstock, Cape Town?

University of Cape Town School of Architecture Planning and Geomatics Enabling ‘Just’ forms Of Regeneration in Woodstock, Cape Town Dissertation submitted in part fulfilment of the degree of University offor Cape Town Master of City and Regional Planning 4 November 2016 By Lewin Rolls Supervisor: Associate Prof Tanja Winkler i The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Declaration of Free Licence The candidate is required to sign a declaration stating: " I hereby: (a) grant the University free license to reproduce the above thesis in whole or in part, for the purpose of research; (b) declare that: (i) the above thesis is my own unaided work, both in conception and execution, and that apart from the normal guidance of my supervisor, I have received no assistance apart from that stated below; (ii) except as stated below, neither the substance or any part of the thesis has been submitted in the past, or is being, or is to be submitted for a degree in the University or any other University. (iii) I am now presenting the thesis for examination the thesis for examination for the Degree of Master of City and Regional Planning.” Plagiarism Declaration form 1. I know that plagiarism is wrong. -

"Little MADEIRA"· the PORTUGUESE in WOODSTOCK C.1940-C.1980

"liTTLE MADEIRA"· THE PORTUGUESE IN WOODSTOCK C.1940-C.1980 Town Pedro Machado Cape of University BUT Cl68 MACH. The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University "LITTLE MADEIRAII- THE PORTUGUESE IN ""OODSTOCK C.1940-C.1980 Pedro Machado Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts(Hons): Department of History, University of Cape Town 1992. I~FORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used. the qUdlity is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "targetll for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page{s)", If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This m~y have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Minutes of Meeting

AGENDA OF HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE'S HERITAGE OFFICERS MEETING (HOMS), TO BE HELD ON MONDAY, 7 December 2020 AT 08H00. PLEASE NOTE DUE TO THE LOCKDOWN THE MEETING WILL BE HELD VIA MICROSOFT TEAMS (HTTPS://TEAMS.MICROSOFT.COM/DOWNLOADS). TO BE A PARTICIPANT IN THE MEETING, KINDLY EMAIL THE ITEM AND CONTACT DETAILS TO [email protected] AHEAD OF THE SCHEDULED TIME. 1. Opening and Welcome 2. Attendance 3. Apologies 4. Approval of Agenda 4.1 Dated 7 December 2020 5. Approval of Minutes of the Previous Meeting 5.1 2 November 2020 5.2 23 November 2020 5.3 26 November 2020 5.4 30 November 2020 6. Disclosure of conflict of interest 7. Confidential matters 8. Standing Items 8.1 Site inspections undertaken 8.2 Proposed Site Inspection 8.3 Site Inspection Reports 8.4 Preparation for the upcoming coming committee meetings 8.4.1 IACom Committee meeting 9 December 2020 8.4.2 BELCom Committee 10 December 2020 8.5 Interim and Close Out Reports 8.5.1 None 8.6 Incomplete Applications 9. Administrative Matters 10. Appointments 10.1 11.17 - Erf 47342, Rondebosch 11.18 - Erf 730, Green Point HOMS Agenda 7 December 2020 1 MATTERS TO BE DISCUSSED 11. Matters Arising 11.1 Proposed additional buildings located on Erf 8731, 225 Main Road,Paarl, Drakenstein, Cape Winelands.S38(4)-NID HM/CAPE WINELANDS/ DRAKENSTEIN/ PAARL / ERF 8731 Case No: 20101510SB1022E SB 11.2 Proposed Alterations and Additions, Erf 9593, 10 Cobern Street, Cape Town CBD. S34-A&A HM/CAPE TOWN METROPOLITAN/ CAPE TOWN CBD/ ERF 9593 Case No: 19091708SB1014E SB 11.3 Proposed new dwelling, Erf 725, 49 Front Street, Gansbaai, Overstrand. -

Western Cape COVID-19 Cases at Town and Suburb Level.1 January

Western Cape COVID-19 at Town and Suburb levels. -

January 2020 Removal Applications.Pdf

South African Police Name under which Services designated liquor Full name of applicant business will be Address of the proposed premises Kind of licence applied for officer office where the Newspaper Publication Date Distribution Area Circulation conducted application has been lodged Firgrove Business Park, Unit C5, 9 1 Eurolane CC Eurolane Quantum Road, Firgrove, Somerset Off-Consumption Somerset West Bolander 29/01/2020 Strand, Somerset West, Franschhoek, Paarl, Stellenbosch, Gordon's Bay, Wellington. 31,150 West Blouberg, Table View, Milnerton, Edgemead, Bothasig, Tygerhof, Sanddrift, Richwood, Blouberg Strand, Milnerton Creation Park, Unit 37 & 38, 2 Ridge, Summer Greens, Melkbosstrand, Sunridge, Flamingo Vlei, West Riding, Duynefontein, Van Riebeeckstrand, Milnerton 2 Anchor Chandling (Pty) Ltd Anchor Chandling Computer Road, Marconi Beam, Off-Consumption TableTalk 29/01/2020 Sunset Beach, West Beach, Parklands, Phoenix, Sunningdale, Blouberg Sands, Killarney Gardens, Montague Gardens, 67,673 Maitland Milnerton Sunset Village, Sunset Links, Big Bay, Joe Slovo Park, Century City Residential, De Noon, Royal Ascot, Brooklyn, Rugby, Paarden Eiland. Woodstock People's Post - Salt River, University Estate, Walmer Estate, Woodstock, Observatory, Paardeneiland, Factreton, Kensington, 3 Rocket Trading 103 CC Honestar Asia Supermarket 359 Albert Road, Woodstock Off-Consumption 28/01/2020 14,825 Gordon’s Bay Woodstock/Maitland Maitland, Maitland Garden Village Crazy Horse Investment (Pty) Shop 37, Mountain Mill Shopping Worcester, Touwsrivier, -

Property Barometer – Cape Town House Price Indices

PROPERTY BAROMETER FNB City of Cape Town House Price Indices The most expensive markets, i.e. those against Table Mountain, appear to have been cooling off noticeably in 16 February 2018 terms of house price growth, but in more affordable sub- regions of the City that’s not quite the case yet Our 4th quarter 2017 City of Cape Town Sub-Regional House Price Indices MARKET ANALYTICS AND continue to show some of the most expensive regions’ house price growth SCENARIO FORECASTING UNIT to be slowing noticeably. But with very expensive home values in recent years in Cape Town encouraging a greater search for affordability, some of the City’s more affordable housing regions appear to have been performing JOHN LOOS: quite well. HOUSEHOLD AND PROPERTY Overall, though, our deeds data-driven City of Cape Town House Price Index SECTOR STRATEGIST continued to show a gradually slowing price growth rate, albeit still strong. 087-328 0151 [email protected] THE OVERALL CITY PICTURE Using Deeds Office Data, we compile a set of house price indices for key sub- regions within the City of Cape Town Metro using a repeat sales methodology. THULANI LUVUNO STATISTICIAN We have then rolled up this set of sub-regions into an overall City of Cape th 087-730 2254 Town Metro House Price Index. In the 4 quarter of 2017, the City of Cape thulani.luvuno@@fnb.co.za Town’s estimated average house price growth rate remained just within double-digit territory to the tune of 10.8% year-on-year. However, while still very strong, this year-on-year price growth rate represents the 6th consecutive quarter of slowing from a 10-year high of 15.7% The information in this publication is nd derived from sources which are regarded as recorded in the 2 quarter of 2016. -

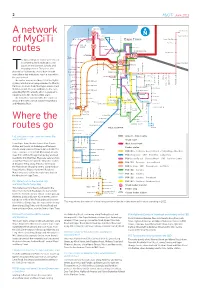

A Network of Myciti Routes Where the Routes Go

2 MyCiTi June 2011 WATERFRONT A network Salt River Rail Breakwater SALT RIVER Granger Marine Mouille Point Nobel Clocktower Lower Salt River Somerset Square Cape Town Hospital of MyCiTi Salt River Lighthouse GREEN Aquarium POINT Foreshore Convention Centre Marina Dock routes CIVIC CENTRE Roodebloem Convention Centre STADIUM Three Anchor Bay he nine permanent routes were chosen Heerengracht to serve important destinations like 137 GP Main Upper Woodstock Lower Bree Adderley places of employment, schools and 27 Somerset 195 GP Main shopping centres. They were also Mid Bree Rocklands Gallows Hill Keizersgracht T Castle planned so that nobody should have to walk Sea Point Library Upper Bree Upper Portswood Riebeeck more than a few minutes to reach a stop within St James Wale Lower Tennant 26 SP Main Bantam the area served. Bo-Kaap Buitenkant CPUT Mid Loop Plein Chester London The routes are part of Phase 1A of the MyCiTi 205 High Level Darling De Villiers Hall system, which is also being extended to Atlantis, Zonnebloem Upper Adderley Walmer Estate 80 SP Main Upper Loop Devil’s Peak Upper Mountain University Estate 243 High Level St Johns Upper Melbourne Graaff’s Du Noon, Jo Slovo Park, Montague Gardens and 65 Buitenkant Pool High Cape 120 SP Main Melkbosstrand. They are additions to the ever- 265 High Level Hatfield 147 Buitenkant extending MyCiTi network, which is planned to Milton’s Villa Maria Pool Tafelberg High Derry expand across the city in coming years. Gardens Lower Burnside Upper Burnside St James The next phase will extend to the southeast 188 SP Main Irwinton Pavillion Upper Buitenkant areas of the metro, which include Khayelitsha 18 Kloof Nek Weltevreden Florida Upper Fresnaye 62 Kloof 43 Kloof Nek and Mitchells Plain. -

Western Cape COVID-19 Cases Allocated to Suburbs. 1 June 2020

Western Cape COVID-19 Cases Allocated to Suburbs. 1 June 2020 WC- Suburbs COVID-19 cases Unallocated 2625 Guguletu 960 NYANGA 542 Khayelitsha 530 Philippi 506 Leiden 491 Langa 440 Mfuleni 394 MASIPHUMELELE 308 Delft 269 Browns Farms 259 Delft South 243 Crossroads 234 Dunoon 218 Ilitha Park 216 Weltevreden Valley North 214 Mandela Park 213 MBEKWENI 209 Wallace Dene 206 Harare 197 Ikwezi Park 186 Manenberg 181 Lentegeur 180 Trevor Vilakazi 165 Lotus River 165 Ravensmead 160 Tafelsig 159 Kuyasa 157 Mandalay 153 Bloekombos 153 Town 3 Village 5 150 De La Haye 148 Bishop Lavis 144 Town 3 Village 3 143 Macassar 131 Gatesville 127 Eyethu 126 Khaya 124 Strand 123 RETREAT 119 Zweletemba 118 Portland 118 Bonteheuwel 117 Grassy Park 113 Nduli 112 Hanover Park 99 WESBANK 95 Beacon Valley 94 LANSDOWNE 93 Imizamo Yethu 92 Kuils River 89 Nonqubela 87 Parklands 86 Wynberg 83 Observatory 83 Scottsdene 77 Woodstock 75 Rocklands 75 Victoria Mxenge 75 Kaya Mandi 74 Ocean View 73 Kenilworth 73 Eastridge 73 Westridge 71 Strandfontein 71 Heideveld 70 LWANDLE 67 Steenberg 66 Groenheuwel 65 Cape Town City Centre 65 Parow 64 Matroosfontein 64 Belhar 63 RONDEBOSCH 62 Maitland 62 PINELANDS 61 Claremont 61 Malibu Village 60 Bellville South 58 Voorbrug 57 SAREPTA 56 Woodlands 56 Scottsville 56 UITSIG 55 Mitchells Plain Centre 55 Fresnaye 55 Asanda 55 Roosendal 53 OTTERY 53 FISANTEKRAAL 53 Bellville 51 Plumstead 49 RYLANDS 49 Somerset West 49 Pelikan Park 49 Strandfontein Village 48 Valhalla Park 47 Salt River 47 Silver Town 47 Silvertown 47 MILNERTON 46 Cravenby 46