Forms of Regeneration in Woodstock, Cape Town?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners

Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1971_45 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 48/71 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Contributor Anti-Apartheid Movement Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1971-11-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, United Kingdom Coverage (temporal) 1971 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Contains a list of addresses provided by the Anti-Apartheid Movement. -

Unrevised Hansard National Council of Provinces

UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL COUNCIL OF PROVINCES TUESDAY, 23 MAY 2017 Page: 1 TUESDAY, 23 MAY 2017 ____ PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF PROVINCES ____ The Council met at 14:01. The House Chairperson: Committees, Oversight, Co-operative Government and Intergovernmental Relations took the Chair and requested members to observe a moment of silence for prayer or meditation. NOTICES OF MOTION Mr D L XIMBI: Thank you Chair. I hereby give notice that on the next sitting day of the Council I shall move on behalf of the ANC: That the Council — (1) debates the illumining publicity around the birthday parties of Western Cape Human Settlements MEC Bonginkosi Madikizela and his partner, Health MEC Nomafrench Mbombo, who reportedly UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL COUNCIL OF PROVINCES TUESDAY, 23 MAY 2017 Page: 2 celebrated their birthdays in expensive hotels attended by and paid for by service providers, contractors or tenders of the provincial government; (2) notes that these parties were co-ordinated by the MECs or their private offices that sought or solicited sponsorships to pay for the unlimited menu choices, open bar and even a cake to the value of R3 000 for Madikizela; and (3) also notes that we implore this Council to institute an investigation to get to the bottom of this apparent abuse of government resources, ... [Inaudible.] ... actions and corrupt exploitation of appointed consultants to entertain these DA MECs, their friends and party benefactors. Ms E PRINS: I hereby give notice that on the next sitting day of the Council I shall move -

University of Cape Town

Town The copyright of this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derivedCape from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of theof source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. University An investigation into the geographical trends in the sectoral composition of the Cape Town economy By Netshikulwe Azwihangwisi NTSAZW002 Supervisor Professor Owen Crankshaw Town A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MastersCape of Social Science in Sociology in the DepartmentOf of Sociology Faculty of the Humanities University University of Cape Town March 2010 Plagiarism Declaration This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotes from people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature Azwihangwisi Netshikulwe September 2009 Town Cape Of University I Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the financial contributions made by the following institutions towards my study: the National Research Foundation (NRF), the Harry Crossley Foundation, the KW Johnstone Research Scholarship and UCT Scholarship. To my supervisor, Professor Owen Crankshaw, your indefinite support and guidance have been a major determinant in my completing this degree. Thank you for assisting me throughout this journey and particularly in the theoretical component and for continuously providing me with data relevant to my study. Your support in my study has been immense and incalculable. I would also like to thank the City of Cape Town staff who provided me with the necessary data to conduct my research. -

INTEGRATED HUMAN SETTLEMENTS FIVE-YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN July 2012 – June 2017 2013/14 REVIEW

INTEGRATED HUMAN SETTLEMENTS FIVE-YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN July 2012 – June 2017 2013/14 REVIEW THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN’S VISION & MISSION The vision and mission of the City of Cape Town is threefold: • To be an opportunity city that creates an enabling environment for economic growth and job creation • To deliver quality services to all residents • To serve the citizens of Cape Town as a well-governed and corruption-free administration The City of Cape Town pursues a multi-pronged vision to: • be a prosperous city that creates an enabling and inclusive environment for shared economic growth and development; • achieve effective and equitable service delivery; and • serve the citizens of Cape Town as a well-governed and effectively run administration. In striving to achieve this vision, the City’s mission is to: • contribute actively to the development of its environmental, human and social capital; • offer high-quality services to all who live in, do business in, or visit Cape Town as tourists; and • be known for its efficient, effective and caring government. Spearheading this resolve is a focus on infrastructure investment and maintenance to provide a sustainable drive for economic growth and development, greater economic freedom, and increased opportunities for investment and job creation. To achieve its vision, the City of Cape Town will build on the strategic focus areas it has identified as the cornerstones of a successful and thriving city, and which form the foundation of its Five-year Integrated Development Plan. The vision is built on five key pillars: THE OPPORTUNITY CITY Pillar 1: Ensure that Cape Town continues to grow as an opportunity city THE SAFE CITY Pillar 2: Make Cape Town an increasingly safe city THE CARING CITY Pillar 3: Make Cape Town even more of a caring city THE INCLUSIVE CITY Pillar 4: Ensure that Cape Town is an inclusive city THE WELL-RUN CITY Pillar 5: Make sure Cape Town continues to be a well-run city These five focus areas inform all the City’s plans and policies. -

It Is Not About The

MyCiTi Bus Service Film Industry Pre-Season Briefing Ronald Kingma Manager IRT Operations Kobus Swanepoel Client Services Transport for Cape Town 11 October 2013 Contents 1. Current System 2. Future Expansion 3. Key Principles 4. Procedure for Filming 5. CCT Fare Policy 6. Application Forms 7. Application Procedure Summary 8. Past film events Current System • Buses : 270 buses • Trunk Routes : Route T01 Wood station – Civic Centre : Route T01a Wood station – V&A Waterfront : Route A01 Airport – V&A Waterfront • Feeder Routes : Route 101 Civic Centre - Gardens : Route 102 Civic Centre – Walmer Estate – Salt River : Route 213 West Beach – Table View - Sunningdale : Route 214 Big Bay – Table View – Parklands : Route 215 Sunningdale- Gie Road - Wood station : Route 216 Sunningdale – Wood Drive – Wood station • Trunk Stations : 17 on Table View, 1 Airport and 4 on Inner City Feeder • Feeder Stops : Inner City: 35 stops : Table View: Over 100 stops • Daily Passengers : 9,000 - 12,000 on weekdays : 2,000 - 5,000 on weekend days • Operation : Approximately 18 hrs per day Future Expansion • 1 November Routes : Route 101 Vredehoek – Gardens - Civic Centre : Route 103 Oranjezicht – Gardens – Civic Centre : Route 104 Sea Point – Waterfront – Civic Centre : Route 105 Sea Point – Fresnaye – Civic Centre : Route 217 Table View - Melkbosstrand : Route 230 Melkbosstrand - Duinefontein • November /Dec : Route 106 Waterfront Silo – Civic Centre – Camps Bay (Clockwise) : Route 107 Waterfront Silo – Civic Centre – Camps Bay (Anti - Clockwise) : Route 251 -

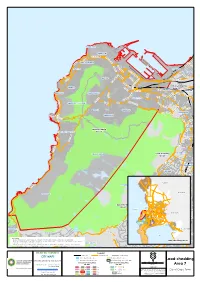

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Annual Report to Citizens 2014/2015

Annual Report to Citizens Who is in charge? The Department is led by the Western Cape Minister of Human Settlements, Mr Bonginkosi Madikizela (left). He is an elected politician appointed as the executive authority of the department. The Head of Department (HOD) is Mr Thando Mguli (right), an appointed public servant who is selected to implement the programmes of the department. Mr Mguli is also the Chief Accounting Officer for the department. Achievements 2014/2015 During the financial year under review, the Department exceeded its housing targets, according to the reporting requirements of the Auditor General. Deliverable Delivered Target Housing Units 10 746 10 357 Serviced Sites 7014 6211 Other housing opportunities 1046 1015 In addition, the department obtained a clean audit for the first time since 1994. The successful service delivery was due, in part, to the following mitigation strategies against underperformance. • Monitoring of delivery was undertaken on a bi-weekly basis throughout the first half of the year to ensure that contractors’ maintained performance and problem areas were timeously addressed. During the last half of the year, the frequency of monitoring was increased. • Regular technical meetings with the staff of the City and other municipalities ensured the alignment of performance reporting as well as the mitigation of detected problems. Active projects were accelerated to make up for delays on slow moving projects. Potential mitigation projects were identified at the beginning of the year to enable this. Our Budget The budget for 2014/2015 was R2 151 327 billion for all programmes. R170 543 000, or 7.9% of the budget, was spent on salaries for 518 employees remunerated during the financial year. -

2011 Census Suburb Woodstock July 2013

City of Cape Town – 2011 Census Suburb Woodstock July 2013 Compiled by Strategic Development Information and GIS Department (SDI&GIS), City of Cape Town 2011 Census data supplied by Statistics South Africa (Based on information available at the time of compilation as released by Statistics South Africa) The 2011 Census suburbs (190) have been created by SDI&GIS grouping the 2011 Census sub-places using GIS and December 2011 aerial photography. A sub-place is defined by Statistics South Africa “is the second (lowest) level of the place name category, namely a suburb, section or zone of an (apartheid) township, smallholdings, village, sub- village, ward or informal settlement.” Suburb Overview, Demographic Profile, Economic Profile, Dwelling Profile, Household Services Profile 2011 Census Suburb Description 2011 Census suburb Woodstock includes the following sub-places: University Estate, Walmer Estate, Woodstock. 1 Data Notes: The following databases from Statistics South Africa (SSA) software were used to extract the data for the profiles: Demographic Profile – Descriptive and Education databases Economic Profile – Labour Force and Head of Household databases Dwelling Profile – Dwellings database Household Services Profile – Household Services database In some Census suburbs there may be no data for households, or a very low number, as the Census suburb has population mainly living in collective living quarters (e.g. hotels, hostels, students’ residences, hospitals, prisons and other institutions) or is an industrial or commercial area. In these instances the number of households is not applicable. All tables have the data included, even if at times they are “0”, for completeness. The tables relating to population, age and labour force indicators would include the population living in these collective living quarters. -

ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 2013–MARCH 2014 Vision: the Creation of Sustainable Human Settlements Through Development Processes Which Enable Human Rights, Dignity and Equity

ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 2013–MARCH 2014 Vision: The creation of sustainable human settlements through development processes which enable human rights, dignity and equity. Mission: To create, implement and support opportunities for community-centred settlement development and to advocate for and foster a pro-poor policy environment which addresses economic, social and spatial imbalances. Umzomhle (Nyanga), Mncediisi Masakhane, RR Section, Participatory Action Planning CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ANC African National Congress KCT Khayelitsha Community Trust BESG Built Environment Support Group KDF Khayelitsha Development Forum Abbreviations 2 BfW Brot für die Welt KHP Khayelitsha Housing Project CBO Community-Based Organisation KHSF Khayelitsha Human Settlements Our team 3 CLP Community Leadership Programme Forum Board of Directors 4 CoCT City of Cape Town (Metropolitan) LED Local economic development Chairperson’s report 5 CORC Community Organisation Resource LRC Legal Resources Centre Centre MIT Massachusetts Institute of Executive Director’s report 6 CBP Capacity-Building Programme Technology From vision to strategy 9 CPUT Cape Peninsula University of NDHS National Department of Human Technology Settlements Affordable housing and human settlements 15 CSO Civil Society Organisation NGO Non-Governmental Organisation Building capacity in the urban sector 20 CTP Cape Town Partnership NDP National Development Plan Partnerships 23 DA Democratic Alliance NUSP National Upgrading Support DAG Development Action Group Programme Institutional change 25 DPU -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

Surfing, Gender and Politics: Identity and Society in the History of South African Surfing Culture in the Twentieth-Century

Surfing, gender and politics: Identity and society in the history of South African surfing culture in the twentieth-century. by Glen Thompson Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert M. Grundlingh Co-supervisor: Prof. Sandra S. Swart Marc 2015 0 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 8 October 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study is a socio-cultural history of the sport of surfing from 1959 to the 2000s in South Africa. It critically engages with the “South African Surfing History Archive”, collected in the course of research, by focusing on two inter-related themes in contributing to a critical sports historiography in southern Africa. The first is how surfing in South Africa has come to be considered a white, male sport. The second is whether surfing is political. In addressing these topics the study considers the double whiteness of the Californian influences that shaped local surfing culture at “whites only” beaches during apartheid. The racialised nature of the sport can be found in the emergence of an amateur national surfing association in the mid-1960s and consolidated during the professionalisation of the sport in the mid-1970s. -

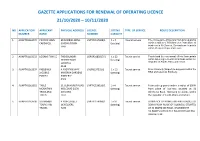

Gazette Applications for Renewal of Operating Licence 21/10/2020 – 10/11/2020

GAZETTE APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL OF OPERATING LICENCE 21/10/2020 – 10/11/2020 NO APPLICATION APPLICANT PHYSICAL ADDRESS LICENCE SITTING TYPE OF SERVICE ROUTE DESCRIPTION NUMBER NAME NUMBER CAPACITY 1. AONPTR1163497 PATRICK JOHN 88 DORRIES DRIVE LNPTR1157888/1 1 x 4 Tourist service The conveyance of tourists from pick up points CARDWELL SIMONS TOWN (seating) within a radius of 60 kilometres from place of 7995 business in 88 Dorries, Simonstown to points within Western Cape and return. 2. AONPTR1163532 LOGANS TAXI CC THE BOUNDRY LGPGP0183817/1 1 x 22 Tourist service Tourist and their personal effects from points DENNIS ROAD (seating) within Gauteng to tourist attractions within the LONEHILL Republic of South Africa and return. 2128 3. AONPTR1163537 FREDERICK 4 AVENTINE WAY LNCPB237532/3 1 x 13 Tourist service From Kimberly (Airport) to any point within the JACOBUS MINERVA GARDENS (seating) RSA and return to Kimberly. POWELL KIMBERLY 8301 4. AONPTR1163552 TABLE 31 GLENHURST ROAD LNPTR1158193/1 1 x 4 Tourist service From pick up points within a radius of 35KM MOUNTAIN WELCOME GLEN (seating) from place of business situated at 31 TREKS AND ATHLONE Glenhurst Road, Glencairn to points within TOURS 7975 the Republic of South Africa and return. 5. AONPTR1163530 SISINAMBO 4 YORK STREET LNPTR1159090/1 1 x 10 Tourist service FROM PICK UP POINTS WITHIN A RADIUS OF TOURS AND DE KELDERS (seating) 35KM FROM PLACE OF BUSINESS SITUATED TRAVEL 7220 AT 35 MARMION ROAD, ORANJEZICHT TO POINTS WITHIN THE BOUNDRIES OF RSA AND RETURN GAZETTE APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL OF OPERATING LICENCE 21/10/2020 – 10/11/2020 6.