John Singleton Copley's Turquerie Portrait of Margaret Kemble Gage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Singleton Copley: Correspondence, 1766-1767

1 JOHN SINGLETON COPLEY: CORRESPONDENCE, 1766-1767 The letters below reflect a critical phase in the career of John Singleton Copley 1738-1815), the most gifted of our native-born Colonial portraitists. In them one finds the beginning of his resolve to leave Boston for study abroad and some of the doubts that beset him before he finally sailed, never to return, in 1774. The pictures he sent to London via Captain R. G. Bruce were the famous Boy with a Squirrel, shown in 1766 at an exhibition of the Society of Artists, and a Little Girl, subsequently lost, which followed in 1767. The paintings were generally well received in London, but the criticism that they were too "liney," opaque, and lacking in "Due Subordination of the Parts," only strengthened Copley's discontent with the provincial city of his birth. Captain R. G. Bruce to Copley DEAR COPLEY, LONDON, 4TH AUGUST, 1766 Don't imagine I have forgot or neglected your Interest by my long Silence. I have delayed writing to You ever since the Exhibition, in order to forward the inclosed Letter from Mr. West, which he has from time to time promised me, but which his extreme Application to his Art has hitherto prevented his finishing. What he says will be much more conclusive to You than anything from me. I have only to add the general Opinions which were pronounced on your Picture when it was exhibited. It was universally allowed to be the best Picture of its kind that appeared on that occasion, but the sentiments of Mr. -

Winslows: Pilgrims, Patrons, and Portraits

Copyright, The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine 1974 PILGRIMS, PATRONS AND PORTRAITS A joint exhibition at Bowdoin College Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Organized by Bowdoin College Museum of Art Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/winslowspilgrimsOObowd Introduction Boston has patronized many painters. One of the earhest was Augustine Clemens, who began painting in Reading, England, in 1623. He came to Boston in 1638 and probably did the portrait of Dr. John Clarke, now at Harvard Medical School, about 1664.' His son, Samuel, was a member of the next generation of Boston painters which also included John Foster and Thomas Smith. Foster, a Harvard graduate and printer, may have painted the portraits of John Davenport, John Wheelwright and Increase Mather. Smith was commis- sioned to paint the President of Harvard in 1683.^ While this portrait has been lost, Smith's own self-portrait is still extant. When the eighteenth century opened, a substantial number of pictures were painted in Boston. The artists of this period practiced a more academic style and show foreign training but very few are recorded by name. Perhaps various English artists traveled here, painted for a time and returned without leaving a written record of their trips. These artists are known only by their pictures and their identity is defined by the names of the sitters. Two of the most notable in Boston are the Pierpont Limner and the Pollard Limner. These paint- ers worked at the same time the so-called Patroon painters of New York flourished. -

Thomas Hutchinson: Traitor to Freedom?

Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 3 June 2018 Thomas Hutchinson: Traitor to Freedom? Kandy A. Crosby-Hastings Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ljh Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Crosby-Hastings, Kandy A. (2018) "Thomas Hutchinson: Traitor to Freedom?," Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ljh/vol2/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Hutchinson: Traitor to Freedom? Abstract Thomas Hutchinson is perhaps one of the most controversial figures of the American Revolution. His Loyalist bent during a time when patriotism and devotion to the American cause was rampant and respected led to his being the target of raids and protests. His actions, particularly his correspondence to Britain regarding the political actions of Bostonians, caused many to question his motives and his allegiance. The following paper will examine Thomas Hutchinson’s Loyalist beliefs, where they originated, and how they affected his political and everyday life. It will examine Thomas Hutchinson’s role during America’s bid for freedom from the Mother Country. Keywords Thomas Hutchinson, Loyalism, the American Revolution Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank my family for supporting me in my writing endeavors. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Heim Gallery Records, 1965-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5779r8sb No online items Finding aid for the Heim Gallery records, 1965-1991 Finding aid prepared by Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Heim Gallery 910004 1 records, 1965-1991 Descriptive Summary Title: Heim Gallery records Date (inclusive): 1965-1991 Number: 910004 Creator/Collector: Heim Gallery Physical Description: 120.0 linear feet(271 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: London gallery directed by Andrew Ciechanowieck. Records include extensive correspondence with museums, galleries, collectors, and other colleagues in Europe and the United States. Photographs document paintings, drawings, sculptures, and decorative art sold and exhibited by, and offered to the gallery. Stock and financial records trace acquisitions and sales. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note Heim Gallery London began in June 1966 with François Heim (from Galerie Heim, Paris, begun 1954) and Andrew S. Ciechanowiecki as partners. Ciechanowiecki served as director in London while Heim remained in France. The emphasis of the gallery was Old Master paintings, especially French of the 15th - 18th century, Italian paintings of all periods, and sculpture (marble, terracotta and bronze) from the Renaissance to the 19th century. The gallery was known for its scholarly exhibitions and catalogs. Between 1966 and 1989 the gallery presented exhibitions two to three times a year. The gallery did business with museums and individual clients in Europe and the United States. -

About Women/Loyalists/Patriot

CK_4_TH_HG_P087_242.QXD 10/6/05 9:02 AM Page 183 Teaching Idea Encourage students to practice read- ing parts of the Declaration of Independence and possibly even Women in the Revolution memorize the famous second section. “Remember the ladies,” wrote Abigail Adams to her husband, John, who was attending the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. While the delegates did not name women in the Declaration of Independence, the “ladies” worked hard for independence. The Daughters of Liberty wove cloth and sewed clothing for the Continental army. Before the war, they had boycotted British imports, including Teaching Idea tea and cloth. The success of these boycotts depended on the support of women, Some women acted as spies during who were responsible for producing most of the household goods. the Revolutionary War. Have students Phillis Wheatley was born in Africa, kidnapped by slavers when she was make invisible ink for getting mes- about seven or eight, and brought to North America. John Wheatley, a rich Boston sages back and forth across enemy merchant, bought her as a servant. His wife, Susannah, taught Wheatley to read lines. For each student, you will need: and write, and she began composing poems as a teenager. Her first book of poet- 4 drops of onion juice, 4 drops of ry was published in London in 1773. The Revolution moved her deeply because lemon juice, a pinch of sugar in a of her own position as a slave, and she composed several poems with patriotic plastic cup, a toothpick to be used as themes, such as “On the Affray [Fighting] in King Street on the Evening of the a writing instrument, and a lamp with 5th of March 1770,” which commemorates the Boston Massacre, and one about an exposed lightbulb. -

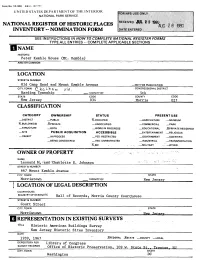

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ [NAME HISTORIC Peter Kemble House (Ht. Kemble)______________________________ AND/OR COMMON ~ ~ ~ ~ '• ~' ~ T LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Old Camp Road and Mount Kemble Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIpNAL DISTRICT Harding Township VICINITY OF 5th STATE CODE COUNTY New Jersey 034 Morris CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL JXPRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION ——MILITARY OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Leonard M. ^rid "Cha)ri<:>tte S. Johnson STREET & NUMBER 667 Mount Kemble-Avenue CITY, TOWN STATE Morris town VICINITY OF New Jersey LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF of Records, Morris County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Court Street CITY, TOWN STATE New REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey _____New Jersey Historic Sites Inventory_____________ DATE 1939, 1967 __ ^FEDERAL J^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR Library of Congress SURVEY RECORDS Office of Historic Preservation, 109 W. State St. f Trenton, NJ CITY. TOWN STATE Washington DC DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE ^_GOOD —RUINS 2LALTERED 2LMOVED DATE_18AHis —FAIR _UNEX POSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Exterior The Kemble House is a five bay clapboard building with a center hall. -

Who Has the 2 President of the United States?

I have Benjamin Franklin. I have Paul Revere. I have the first card. Who has a prominent member of the Continental Congress Benjamin Franklin was a prominent that helped with the member of the Continental Declaration of Congress, who helped with the Paul Revere was a Patriot who Declaration of Independence. warned the British were coming. Independence? Who has a patriot who made a daring ride to warn Who has the ruler who colonists of British soldier’s taxed on the colonies? arriving? I have King George III I have the Daughters of Liberty. I have Loyalist. Loyalists were colonists who remained loyal to England King George III taxed the during the Revolutionary The Daughters of Liberty spun colonies. period. Who has the group that cloth in support or the boycott of English goods. Who has the group formed included Martha Washington Who has the term for a in response to the Stamp that spun cloth to support colonist that remained loyal to Act, which is responsible for the boycott of English England? the Boston Tea Party? goods? I have the Sons of Liberty. I have Nathan Hale. I have Patriot. The Sons of Liberty were formed in response to the Stamp Act. Nathan Hale was a Patriot spy that Patriots were in favor of They were responsible for the was hung by the British. independence from England. Boston Tea Party. Who has the American Who has the term for a nd colonist in favor of Who has the 2 spy who was hung by independence from president of the the British? England? United States? I have the John Adams. -

DID JOSHUA REYNOLDS PAINT HIS PICTURES? Matthew C

DID JOSHUA REYNOLDS PAINT HIS PICTURES? Matthew C. Hunter Did Joshua Reynolds Paint His Pictures? The Transatlantic Work of Picturing in an Age of Chymical Reproduction In the spring of 1787, King George III visited the Royal Academy of Arts at Somerset House on the Strand in London’s West End. The king had come to see the first series of the Seven Sacraments painted by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) for Roman patron Cassiano dal Pozzo in the later 1630s. It was Poussin’s Extreme Unction (ca. 1638–1640) (fig. 1) that won the king’s particular praise.1 Below a coffered ceiling, Poussin depicts two trains of mourners converging in a darkened interior as a priest administers last rites to the dying man recumbent on a low bed. Light enters from the left in the elongated taper borne by a barefoot acolyte in a flowing, scarlet robe. It filters in peristaltic motion along the back wall where a projecting, circular molding describes somber totality. Ritual fluids proceed from the right, passing in relay from the cerulean pitcher on the illuminated tripod table to a green-garbed youth then to the gold flagon for which the central bearded elder reaches, to be rubbed as oily film on the invalid’s eyelids. Secured for twenty-first century eyes through a spectacular fund-raising campaign in 2013 by Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, Poussin’s picture had been put before the king in the 1780s by no less spirited means. Working for Charles Manners, fourth Duke of Rutland, a Scottish antiquarian named James Byres had Poussin’s Joshua Reynolds, Sacraments exported from Rome and shipped to London where they Diana (Sackville), Viscountess Crosbie were cleaned and exhibited under the auspices of Royal Academy (detail, see fig. -

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

Descriptive Catalogue of the Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings and of the Walker Collection

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Museum of Art Collection Catalogues Museum of Art 1930 Descriptive Catalogue of the Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings and of the Walker Collection Bowdoin College. Museum of Art Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/art-museum-collection- catalogs Recommended Citation Bowdoin College. Museum of Art, "Descriptive Catalogue of the Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings and of the Walker Collection" (1930). Museum of Art Collection Catalogues. 4. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/art-museum-collection-catalogs/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum of Art at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Museum of Art Collection Catalogues by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/descriptivecatal00bowd_2 BOWDOIN MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS WALKER ART BUILDING DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGUE OF THE PAINTINGS, SCULPTURE and DRAWINGS and of the WALKER COLLECTION FOURTH EDITION Price Fifty Cents BRUNSWICK, MAINE 1930 THE RECORD PRES5 BRUNSWICK, MAINE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE List of Illustrations 3 Prefatory Note 4 Historical Introduction 8 The Walker Art Building 13 Sculpture Hall 17 The Sophia Walker Gallery 27 The Bowdoin Gallery 53 The Boyd Gallery 96 Base:.:ent 107 The Assyrian Room 107 Corridor 108 Class Room 109 King Chapel iio List of Photographic Reproductions 113 Index ...115 Finding List of Numbers 117 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS FACING PAGE Walker Art Building — Frontispiece Athens, by John La Farge 17 Venice, by Kenyon Cox 18 Rome, by Elihu Vcdder 19 Florence, hy Abbott Thayer 20 Alexandrian Relief Sculpture, SH-S 5 .. -

In-Class Essay Instructions

IN-CLASS ESSAY INSTRUCTIONS Contents Date Introduction Topic Research Outline Instructions References Structure of Paper Grading of Paper Date In class, Wednesday, November 20 Introduction Read this before you proceed further: 1. This document contains live links to internet material; therefore, access it while online. 2. Make-up for this assignment is only possible with a legitimate documented excuse and only during my office hours. 3. Writing a biography of a director you have not been assigned will earn you an automatic F. You have been warned! 4. Do not send me e-mails if you have questions about this assignment; instead come and see me during my office hours. 5. Bring to class a one-page outline of the paper. See instructions below. Warning: The outline is not optional, so if you don’t bring an outline as prepared per instructions below, you will get an automatic F for the paper. 6. No references can be from anything written by me, nor can it be from Wikipedia or any other encyclopedia. (However, you can consult these materials while doing your research—you just can’t use them as references.) 7. You will hand in the outline together with the sheets of paper that will be provided (which you must number and have your names on all of them) on which you will write your essay neatly arranged. 8. Your in-class essay must be structured as per instructions below. 9. You will not be permitted to use any other materials besides the one-page outline. 10. You will lose points for failing to follow any one or more of these instructions (including the possibility of getting an F). -

How Did Women Support the Patriots During the American Revolutionary War?

Educational materials developed through the Howard County History Labs Program, a partnership between the Howard County Public School System and the UMBC Center for History Education. How did Women Support the Patriots During the American Revolutionary War? Historical Thinking Skills Assessed: Sourcing, Critical Reading, Contextualization Author/School/System: Barbara Baker and Drew DiMaggio, Howard County School Public School System, Maryland Course: United States History Level: Elementary Task Question: How did women support the Patriots during the American Revolutionary War? Learning Outcomes: Students will be able to contextualize and corroborate two sources to draw conclusions about women’s contributions to the American Revolution. Standards Alignment: Common Core Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy RI.5.3 Explain the relationships or interactions between two or more individuals, events, ideas, or concepts in a historical, scientific, or technical text based on specific information in the text. W.5.1 Write opinion pieces on topics or texts, supporting a point of view with reasons and information. SL.5.1 Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions with diverse partners on grade 5 topics and texts, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly. SL.5.1a Come to discussions prepared, having read or studied required material; explicitly draw on that preparation and other information known about the topic to explore ideas under discussion. SL.5.1d Review the key ideas expressed and draw conclusions in light of information and knowledge gained from the discussions. National History Standards Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s) Standard 2: The impact of the American Revolution on politics, economy, and society College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies Standards D2.His.5.3-5 Explain connections among historical contexts and people’s perspectives at the time.