West Ndion Tuskers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology the University of Michigan

CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN VOL. 29.. No. 3. PP. 69-87 November 30. 1994 PROTOSIREN SMITHAE, NEW SPECIES (MAMMALIA, SIRENIA), FROM THE LATE MIDDLE EOCENE OF WADI HITAN, EGYPT BY DARYL P. DOMNING AND PHILIP D. GINGERICH MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY Philip D. Gingerich, Director This series of contributions from the Museum of Paleontology is a medium for publication of papers based chiefly on collections in the Museum. When the number of pages issued is sufficient to make a volume, a title page and a table of contents will be sent to libraries on the mailing list, and to individuals on request. A list of the separate issues may also be obtained by request. Correspondence should be directed to the Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48 109-1079. VOLS. 2-29. Parts of volumes may be obtained if available. Price lists are available upon inquiry. PROTOSIREN SMITHAE, NEW SPECIES (MAMMALIA, SIRENIA), FROM THE LATE MIDDLE EOCENE OF WADI KITAN, EGYPT Abstract-Protosiren smithae is a new protosirenid sirenian described on the basis of associated cranial and postcranial material from the late middle Eocene (latest Bartonian) Gehannam Formation of Wadi Hitan (Zeuglodon Valley), Fayum Province, Egypt. The new species is similar to Protosiren fraasi Abel, 1907, from the earlier middle Eocene (Lutetian) of Egypt, but it is younger geologically and more derived morphologically. P. smithae is probably a direct descendant of P. fraasi. The postcranial skeleton of P. imithae- includes well-developed hindlimbs, which suggest some lingering amphibious tendencies in this otherwise aquatically-adapted primitive sea cow. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

A new marine vertebrate assemblage from the Late Neogene Purisima Formation in Central California, part II: Pinnipeds and Cetaceans Robert W. BOESSENECKER Department of Geology, University of Otago, 360 Leith Walk, P.O. Box 56, Dunedin, 9054 (New Zealand) and Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University 200 Traphagen Hall, Bozeman, MT, 59715 (USA) and University of California Museum of Paleontology 1101 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley, CA, 94720 (USA) [email protected] Boessenecker R. W. 2013. — A new marine vertebrate assemblage from the Late Neogene Purisima Formation in Central California, part II: Pinnipeds and Cetaceans. Geodiversitas 35 (4): 815-940. http://dx.doi.org/g2013n4a5 ABSTRACT e newly discovered Upper Miocene to Upper Pliocene San Gregorio assem- blage of the Purisima Formation in Central California has yielded a diverse collection of 34 marine vertebrate taxa, including eight sharks, two bony fish, three marine birds (described in a previous study), and 21 marine mammals. Pinnipeds include the walrus Dusignathus sp., cf. D. seftoni, the fur seal Cal- lorhinus sp., cf. C. gilmorei, and indeterminate otariid bones. Baleen whales include dwarf mysticetes (Herpetocetus bramblei Whitmore & Barnes, 2008, Herpetocetus sp.), two right whales (cf. Eubalaena sp. 1, cf. Eubalaena sp. 2), at least three balaenopterids (“Balaenoptera” cortesi “var.” portisi Sacco, 1890, cf. Balaenoptera, Balaenopteridae gen. et sp. indet.) and a new species of rorqual (Balaenoptera bertae n. sp.) that exhibits a number of derived features that place it within the genus Balaenoptera. is new species of Balaenoptera is relatively small (estimated 61 cm bizygomatic width) and exhibits a comparatively nar- row vertex, an obliquely (but precipitously) sloping frontal adjacent to vertex, anteriorly directed and short zygomatic processes, and squamosal creases. -

Zeezoogdieren

CRANIUM, nr. 2 -1998 De Nederlandse fossiele zeezoogdieren. Een overzicht Klaas Post Samenvatting Onder de worden in dit Cetacea de noemer zeezoogdieren artikel de (walvissen en dolfijnen), Pinnipedia de Sirenia Fossielen worden (zeehonden, zeeleeuwen en walrussen) en (zeekoeien) samengevat. van zeezoogdieren dan Naast het feit dat zeldzaam is hun veel minder aangetroffen fossielen van landzoogdieren. ze gewoon zijn voorkomen ook recente of fossiele zeebodems en stranden. nog beperkt tot specifieke gebieden: namelijk en is de evolutie bekend dus is de of Dientengevolge er nogweinig over van zeezoogdieren en genus- soortbepaling of Verder vooral oudere literatuur foutieve informatiete bevatten en vaak nog moeilijk geheel nietmogelijk. blijkt bovendien aantal verschillende dezelfde vermelden.Het is danook niet een enorm namen voor genera en soorten te verwonderlijk dat fossiele zeezoogdieren wetenschappelijk noch populair in de belangstelling staan. De de Noordzee behoren de wereld van fossielen van Nederlanden en aangrenzende tot rijkste vindplaatsen ter zeezoogdieren. Hoe kan het ook eigenlijk anders met zo’n waterrijke geologische geschiedenis. De voortdurend Pleistoceen het Holoceenincombinatie met wisselendeNoordzeekustlijnen gedurende Mioceen,Plioceen, en vroege de vele rivieren hebben Zo worden de mondingen van grote zeer gevarieerde zeezoogdierfauna’s nagelaten. de Pleistocene walrus wereld zoveel fossielen als in Nederland! Ondanks de bijvoorbeeld van nergens ter gevonden kwaliteit deze heeft de eind links laten De kwantiteit en van fossielen wetenschap ze sinds vorige eeuw liggen. helaas vaak verloren collecties verkeren veelal in slechte staat en de bijbehorende gegevens zijn gegaan. Summary lions and and the Sirenia In this article the Cetacea (wales and delphins), the Pinnipedia (seals, sea walrusses) (sea unitedunder the mammals.Fossils of mammals found lesser thanthose of land cows) are term sea sea are to a extent also: and fossil mammals. -

APPENDIX 4. Classification and Synonymy of the Sirenia and Desmostylia

revised 3/29/2010 APPENDIX 4. Classification and Synonymy of the Sirenia and Desmostylia The following compilation encapsulates the nomenclatural history of the Sirenia and Desmostylia as comprehensively as I have been able to trace it. Included are all known formal names of taxa and their synonyms and variant combinations, with abbreviated citations of the references where these first appeared and their dates of publication; statements of the designated or inferred types of these taxa and their provenances; and comments on the nomenclatural status of these names. Instances of the use of names or combinations subsequent to their original publication are, however, not listed. Of course, the choices of which taxa to recognize as valid and their proper arrangement reflect my own current views. This arrangement is outlined immediately hereafter to aid in finding taxa in this section. (Note that not all taxa in this summary list are necessarily valid; several are probable synonyms but have not been formally synonymized.) For a quick-reference summary of the names now in use for the Recent species of sirenians, see Appendix 5. – DPD Summary Classification and List of Taxa Recognized ORDER SIRENIA Illiger, 1811 Family Prorastomidae Cope, 1889 Pezosiren Domning, 2001 P. portelli Domning, 2001 Prorastomus Owen, 1855 P. sirenoides Owen, 1855 Family Protosirenidae Sickenberg, 1934 Ashokia Bajpai, Domning, Das, and Mishra, 2009 A. antiqua Bajpai, Domning, Das, and Mishra, 2009 Protosiren Abel, 1907 P. eothene Zalmout, Haq, and Gingerich, 2003 P. fraasi Abel, 1907 P. sattaensis Gingerich, Arif, Bhatti, Raza, and Raza, 1995 P. smithae Domning and Gingerich, 1994 ?P. minima (Desmarest, 1822) Hooijer, 1952 Family Trichechidae Gill, 1872 (1821) Subfamily Miosireninae Abel, 1919 Anomotherium Siegfried, 1965 1 Daryl P. -

Marine Mammals from the Miocene of Panama

Journal of South American Earth Sciences 30 (2010) 167e175 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of South American Earth Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsames Marine mammals from the Miocene of Panama Mark D. Uhen a,*, Anthony G. Coates b, Carlos A. Jaramillo b, Camilo Montes b, Catalina Pimiento b,c, Aldo Rincon b, Nikki Strong b, Jorge Velez-Juarbe d a George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA b Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Box 0843-03092, Balboa, Ancon, Panama c Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA d Laboratory of Evolutionary Biology, Department of Anatomy, Howard University, WA 20059, USA article info abstract Article history: Panama has produced an abundance of Neogene marine fossils both invertebrate (mollusks, corals, Received 1 May 2009 microfossils etc.) and vertebrate (fish, land mammals etc.), but marine mammals have not been previ- Accepted 21 August 2010 ously reported. Here we describe a cetacean thoracic vertebra from the late Miocene Tobabe Formation, a partial cetacean rib from the late Miocene Gatun Formation, and a sirenian caudal vertebra and rib Keywords: fragments from the early Miocene Culebra Formation. These finds suggest that Central America may yet Panama provide additional fossil marine mammal specimens that will help us to understand the evolution, and Neogene particularly the biogeography of these groups. Miocene Ó Pliocene 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Cetacea Sirenia 1. Introduction archipelago, Panama (Fig. 1A). The Tobabe Formation is the basal unit of the Late Miocene-Early Pliocene (w7.2ew3.5 Ma) Bocas del Central America includes an abundance of marine sedimentary Toro Group, an approximately 600 m thick succession of volcani- rock units that have produced many fossil marine invertebrates clastic marine sediments (Fig. -

Miocene Paleontology and Stratigraphy of the Suwannee River Basin of North Florida and South Georgia

MIOCENE PALEONTOLOGY AND STRATIGRAPHY OF THE SUWANNEE RIVER BASIN OF NORTH FLORIDA AND SOUTH GEORGIA SOUTHEASTERN GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Guidebook Number 30 October 7, 1989 MIOCENE PALEONTOLOGY AND STRATIGRAPHY OF THE SUWANNEE RIVER BASIN OF NORTH FLORIDA AND SOUTH GEORGIA Compiled and edit e d by GARY S . MORGAN GUIDEBOOK NUMBER 30 A Guidebook for the Annual Field Trip of the Southeastern Geological Society October 7, 1989 Published by the Southeastern Geological Society P. 0 . Box 1634 Tallahassee, Florida 32303 TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of field trip area ...... ... ................................... 1 Road log . ....................................... ..... ..... ... .... 2 Preface . .................. ....................................... 4 The lithostratigraphy of the sediments exposed along the Suwannee River in the vicinity of White Springs by Thomas M. scott ........................................... 6 Fossil invertebrates from the banks of the Suwannee River at White Springs, Florida by Roger W. Portell ...... ......................... ......... 14 Miocene vertebrate faunas from the Suwannee River Basin of North Florida and South Georgia by Gary s. Morgan .................................. ........ 2 6 Fossil sirenians from the Suwannee River, Florida and Georgia by Daryl P. Damning . .................................... .... 54 1 HAMIL TON CO. MAP OF FIELD TRIP AREA 2 ROAD LOG Total Mileage from Reference Points Mileage Last Point 0.0 0.0 Begin at Holiday Inn, Lake City, intersection of I-75 and US 90. 7.3 7.3 Pass under I-10. 12 . 6 5.3 Turn right (east) on SR 136. 15.8 3 . 2 SR 136 Bridge over Suwannee River. 16.0 0.2 Turn left (west) on us 41. 19 . 5 3 . 5 Turn right (northeast) on CR 137. 23.1 3.6 On right-main office of Occidental Chemical Corporation. -

117 October 2013—PROGRAM and ABSTRACTS

Technical Session XV (Saturday, November 2, 2013, 9:45 AM) which is situated on the eastern Bolivian Altiplano (21° 52’ S, 66° 19’ W), several THE SIRENIAN GENUS METAXYTHERIUM: WHAT'S UP WITH THOSE kilometers southeast of the village of Cerdas (approx. 60 km southeast of Uyuni). Eight ANIMALS?? specimens were studied including several partial mandibles preserving posterior premolars and molars, a partial maxilla with P3-P4, two fragmentary dentaries preserving DOMNING, Daryl, Howard Univ., Washington, DC, United States, 20059; VELEZ- alveoli of the anterior dentition, several isolated cheek teeth, an upper incisor, and two JUARBE, Jorge, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL, United States calcanei. The specimens are referred to the Hegetotheriinae based on the absence of a Metaxytherium (Mammalia, Dugongidae) is one of the most widespread, long-lived, strongly trilobed m3 talonid, lack of conspicuous diastemata among i2-p2 alveoli, and a species-rich, commonly fossilized – and taxonomically troublesome – genera of Sirenia. relatively small I1. A Hegetotheriine affinity is supported by the two Cerdas calcanei, Its morphologically conservative nature had, until recently, made it difficult to properly which are more similar to Hegetotherium than Pachyrukhos in having a circular define this genus. In recent years, however, much has been done to clarify its contents, sustentacular facet, a large navicular facet, and an only moderately rugose tuber. The relationships, and eventful evolutionary history. Originally known only from the Miocene Cerdas species differs from Prohegetotherium in lacking a labial groove near the anterior and Pliocene, its presence in the New World late Oligocene is now established, along margin of the upper cheek teeth. -

The Sirenia of the Mediterranean Tertiary

THE SIRENIA OF THE MEDITERRANEAN TERTIARY FORMATIONS OF AUSTRIA Geologische Bundesanstalt Abhandlungen 19, 1902-1904 O. Abel* III Description. Metaxytherium petersi Abel 1904. Synonymy: See Original: Geological distribution. Second Mediterranean stage. Geographic Distribution. Known only from the interalpine depression of the Vienna Basin, (Eggenburg, Neurdort on the March, Mannersdorf in the Leitha Mountains, Wollersdorf near Wiener Neustadt, Voeslau, Kalksburg, Perchtoldsdorf, Ottakring, Garschental near Feldsberg). 1. Skull. (Neudorf on the March) A very incomplete fragment of the posterior section of the roof of the skull including a portion of the left parietal and the uppermost section of the supraoccipital is all that represents * Original citation: Abel, O. 1904. Die Sirenen der mediterranen Tertiarbildungen Oesterreichs. Abhandlungen Geologische Reichsanstalt, Wien 19:1-223 (partim). Unknown translator. Transferred to electronic copy and edited by Mark Uhen and Michell Kwon, Smithsonian Institution, 2007. the skull of Metaxytherium petersi of Neudorf. Considering the thinness of the bones these remains belonged to a young animal. It is very noticeable that in spite of the thinness of the bones of the skull, the width of the roof of the skull is almost exactly the same as in a skull of a full-grown individual of Metaxytherium krahuletzi from Eggenburg. The size of the supraoccipital is only 8 mm under the superior linea nuchae. The width of the roof of this skull is nearly as great as the width of the roof of the skull of the same species from the “Muschelsantsteine” of Wuerenlos (Kanton Aargau). It is 77 mm while the width of the roof of the skull of Eggenburg is 94 mm. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

New record of Metaxytherium (Mammalia, Sirenia) from the lower Miocene of Manosque (Provence, France) Silvia SORBI Università di Pisa, Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, via S. Maria 53, I-56126 Pisa (Italy) [email protected] Sorbi S. 2008. — New record of Metaxytherium(Mammalia, Sirenia) from the lower Miocene of Manosque (Provence, France). Geodiversitas 30 (2) : 433-444. ABSTRACT A new specimen of Metaxytherium (Mammalia, Sirenia) consisting of a skull with associated thoracic vertebrae and ribs from the lower Miocene “Molasse calcaire et sablo-marneuse Formation” of Manosque (Provence, France) is described. The specimen is referred toMetaxytherium cf. krahuletzi on the basis of geological age, but its anatomical characters, size and proportions are also KEY WORDS Mammalia, consistent with Metaxytherium medium.The difficulty of separating these two Sirenia, species is confirmed. The species of the genus Metaxytherium show morpho- Metaxytherium, logical stasis over a period of more than 10 million years. This new specimen, Miocene, Mediterranean domain, however, provides new information about the continuity of the Miocene Old France. World Metaxytherium record. RÉSUMÉ Un nouveau Metaxytherium (Mammalia, Sirenia) dans le Miocène inférieur de Manosque (Provence, France). Un nouveau spécimen du genre Metaxytherium (Mammalia, Sirenia) est décrit d’après un crâne et une mandibule, associés à plusieurs vertèbres thoraciques et des côtes. Il provient de la formation de Molasse calcaire et sablo-marneuse du Miocène inférieur de Manosque (Provence, France). Il est attribué à Meta xytherium cf. krahuletzi d’après l’âge des dêpots, mais ses caractères anatomiques, sa taille et ses proportions sont également compatibles avec Metaxytherium MOTS CLÉS Mammalia, medium. -

Evolution of the Sirenia: an Outline

Caryn Self-Sullivan, Daryl P. Domning, and Jorge Velez-Juarbe Last Updated: 8/1/14 Page 1 of 10 Evolution of the Sirenia: An Outline The order Sirenia is closely associated with a large group of hoofed mammals known as Tethytheria, which includes the extinct orders Desmostylia (hippopotamus-like marine mammals) and Embrithopoda (rhinoceros-like mammals). Sirenians probably split off from these relatives in the Palaeocene (65-54 mya) and quickly took to the water, dispersing to the New World. This outline attempts to order all the species described from the fossil record in chronological order within each of the recognized families of Prorastomidae, Protosirenidae, Dugongidae, and Trichechidae. This outline began as an exercise in preparation for my Ph. D. preliminary exams and is primarily based on decades of research and peer-reviewed literature by Dr. Daryl P. Domning, to whom I am eternally grateful. It has been recently updated with the help of Dr. Jorge Velez-Juarbe. However, this document continues to be a work-in-progress and not a peer reviewed publication! Ancestral line: Eritherium Order Proboscidea Elephantidae (elephants and mammoths) Mastodontidae Deinotheriidae Gomphotheriidae Ancestral line: Behemotops Order Desmostylia (only known extinct Order of marine mammal) Order Sirenia Illiger, 1811 Prorastomidae Protosirenidae Dr. Daryl Domning, Howard University, November 2007 Dugongidae with Metaxytherium skull. Photo © Caryn Self-Sullivan Trichechidae With only 5 species in 2 families known to modern man, you might be surprised to learn that the four extant species represent only a small fraction of the sirenians found in the fossil record. As of 2012, ~60 species have been described and placed in 4 families. -

Evolutionary Paleoecology of the Maryland Miocene

The Geology and Paleontology of Calvert Cliffs Calvert Formation, Calvert Cliffs, South of Plum Point, Maryland. Photo by S. Godfrey © CMM A Symposium to Celebrate the 25th Anniversary of the Calvert Marine Museum’s Fossil Club Program and Abstracts November 11, 2006 The Ecphora Miscellaneous Publications 1, 2006 2 Program Saturday, November 11, 2006 Presentation and Event Schedule 8:00-10:00 Registration/Museum Lobby 8:30-10:00 Coffee/Museum Lobby Galleries Open Presentation Uploading 8:30-10:00 Poster Session Set-up in Paleontology Gallery Posters will be up all day. 10:00-10:05 Doug Alves, Director, Calvert Marine Museum Welcome 10:05-10:10 Bruce Hargreaves, President of the CMMFC Welcome Induct Kathy Young as CMMFC Life Member 10:10-10:30 Peter Vogt & R. Eshelman Significance of Calvert Cliffs 10:30-11:00 Susan Kidwell Geology of Calvert Cliffs 11:00-11-15 Patricia Kelley Gastropod Predator-Prey Evolution 11:15-11-30 Coffee/Juice Break 11:30-11:45 Lauck Ward Mollusks 11:45-12:00 Bretton Kent Sharks 12:00-12:15 Michael Gottfried & L. Compagno C. carcharias and C. megalodon 12:15-12:30 Anna Jerve Lamnid Sharks 12:30-2:00 Lunch Break Afternoon Power Point Presentation Uploading 2:00-2:15 Roger Wood Turtles 2:15-2:30 Robert Weems Crocodiles 2:30-2:45 Storrs Olson Birds 2:45-3:00 Michael Habib Morphology of Pelagornis 3:00-3:15 Ralph Eshelman, B. Beatty & D. Domning Terrestrial Vertebrates 3:15-3:30 Coffee/Juice Break 3:30-3:45 Irina Koretsky Seals 3:45-4:00 Daryl Domning Sea Cows 4:00-4:15 Jennifer Gerholdt & S. -

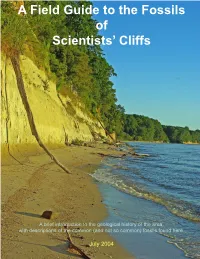

A Field Guide to the Fossils of Scientists' Cliffs

A Field Guide to the Fossils of Scientists’ Cliffs A brief introduction to the geological history of the area, with descriptions of the common (and not so common) fossils found here. July 2004 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 0 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 OBJECTIVES ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 SCOPE .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.5 APPLICABLE DOCUMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.6 DOCUMENT ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................................................... 5 2. GEOLOGY .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 2.1 NAMING ROCK/SOIL UNITS ...............................................................................................................................