10 Language Centre As Language Revitalisation Strategy: a Case Study from the Pilbara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's New in Native Title

WHAT’S NEW IN NATIVE TITLE JUNE 2018 1. Case Summaries _______________________________________________ 1 2. Legislation ____________________________________________________ 9 3. Native Title Determinations _______________________________________ 9 4. Registered Native Title Bodies Corporate & Prescribed Bodies Corporate ___ 9 5. Indigenous Land Use Agreements _________________________________ 10 6. Future Act Determinations _______________________________________ 11 7. Publications __________________________________________________ 13 8. Training and Professional Development Opportunities _________________ 13 9. Events ______________________________________________________ 14 1. Case Summaries Quall v Northern Land Council [2018] FCA 989 29 June 2018, Practice and Procedure, Federal Court of Australia – Northern Territory, Reeves J In this matter the Court declared that the first respondent, the Northern Land Council (NLC), had not certified an application for the registration of the Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) in accordance with s 24CG(3)(a) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA), and in performance of its functions as a representative body under s 203BE(1)(b) of the NTA. The ILUA was dated 21 July 2016 and amended by a Deed of Variation dated 2 February 2017, known as the Kenbi ILUA. The Court ordered that the first respondent pay the applicant’s costs. The applicant was Mr Kevin Quall. The respondents to the claim were the Northern Land Council, and Joe Morrison as Chief Executive Officer of the Northern Land Council. The NLC had submitted a certification of the ILUA which was signed by Mr Joe Morrison, acting in his capacity as CEO of NLC. The issue was not with the contents of this agreement, but whether the CEO could validly sign the certification of the agreement and therefore meet the requirements of s 203 BE(1)(b) NTA. -

![AR Radcliffe-Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4080/ar-radcliffe-brown-684080.webp)

AR Radcliffe-Brown]

P129: The Personal Archives of Alfred Reginald RADCLIFFE-BROWN (1881- 1955), Professor of Anthropology 1926 – 1931 Contents Date Range: 1915-1951 Shelf Metre: 0.16 Accession: Series 2: Gift and deposit register p162 Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was born on 17 January 1881 at Aston, Warwickshire, England, second son of Alfred Brown, manufacturer's clerk and his wife Hannah, nee Radcliffe. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A. 1905, M. A. 1909), graduating with first class honours in the moral sciences tripos. He studied psychology under W. H. R. Rivers, who, with A. C. Haddon, led him towards social anthropology. Elected Anthony Wilkin student in ethnology in 1906 (and 1909), he spent two years in the field in the Andaman Islands. A fellow of Trinity (1908 - 1914), he lectured twice a week on ethnology at the London School of Economics and visited Paris where he met Emily Durkheim. At Cambridge on 19 April 1910 he married Winifred Marie Lyon; they were divorced in 1938. Radcliffe-Brown (then known as AR Brown) joined E. L. Grant Watson and Daisy Bates in an expedition to the North-West of Western Australia studying the remnants of Aboriginal tribes for some two years from 1910, but friction developed between Brown and Mrs. Bates. Brown published his research from that time in an article titled “Three Tribes of Western Australia”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 43, (Jan. - Jun., 1913), pp. 143-194. At the 1914 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Melbourne, Daisy Bates accused Brown of gross plagiarism. -

WA Health Language Services Policy

WA Health Language Services Policy September 2011 Cultural Diversity Unit Public Health Division WA Health Language Services Policy Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Government policy obligations ................................................................................................... 2 2. Policy goals and aims .................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Scope......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Guiding principles ............................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 6. Provision of interpreting and translating services .................................................................... -

10. Remotefocus and Pilbara Aboriginal People 103

remoteFOCUS The Challenge, Conversation, Commissioned Papers and Regional Studies of Remote Australia August 2012 Edited by: Dr Bruce Walker Commissioned Papers by: Dr Mary Edmunds Professor Ian Marsh An initiative facilitated by Desert Knowledge Australia and supported by: i This collection of reports has been edited by: Dr Bruce W Walker, remoteFOCUS Project Director With contributions by: Dr Mary Edmunds, Edmunds Consulting Pty Ltd Professor Ian Marsh, Adjunct Professor, Australian Innovation Research Centre, University of Tasmania The work is reviewed by the remoteFOCUS Reference Group: Hon Fred Chaney AO (Convenor) Dr Peter Shergold AC Mr Neil Westbury PSM Mr Bill Gray AM Mr John Huigen (CEO Desert Knowledge Australia) Any views expressed here are those of the individuals and the remoteFOCUS team and should not be taken as representing the views of their employers. Citation: Walker BW, (Ed) 2012 The Challenge, Conversation, Commissioned Papers and Regional Studies of Remote Australia, Desert Knowledge Australia, Alice Springs Copyright: Desert Knowledge Australia 2012 ISBN: 978-0-9873958-1-8 Associated Reports: Walker, BW, Edmunds, M and Marsh, I. 2012 Loyalty for Regions: Governance Reform in the Pilbara, report to the Pilbara Development Commission, Desert Knowledge Australia ISBN: 978-0-9873958-0-1 Walker, BW, Porter DJ, and Marsh, I. 2012 Fixing the Hole in Australia’s Heartland: How Government needs to work in remote Australia, Desert Knowledge Australia. ISBN: 978-0-9873958-2-5 ISBN Online: 978-0-9873958-3-2 Copyright: Desert Knowledge Australia 2012 Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike Licence For additional information please contact: Dr Bruce Walker Project Director | remoteFOCUS M: 0418 812 119 P: 08 8959 6125 E: [email protected] W: www.desertknowledge.com.au/Our-Programs/remoteFOCUS P: 08 8959 6000 E: [email protected] i remoteFOCUS The Challenge, Conversation, Commissioned Papers and Regional Studies of remote Australia The Challenge Chapter 1. -

ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES of the GASCOYNE-ASHBURTON REGION Peter Austin 1

ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES OF THE GASCOYNE-ASHBURTON REGION Peter Austin 1. INTRODUCTION1 This paper is a description of the language situation in the region between the Gascoyne and Ashburton Rivers in the north-west of Western Australia. At the time of first white settlement in the region, there were eleven languages spoken between the two rivers, several of them in a number of dialect forms. Research on languages of the locality has taken place mainly in the past thirty years, after a long period of neglect, but details of the past and present linguistic situation have been emerging as a result of that research. The paper includes an annotated bibliography of the Aboriginal languages traditionally spoken in the area 2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The first explorations by Europeans in the north-west of Western Australia were maritime voyages concerned with coastal exploration. As early as 1818, Captain P.P. King had reported on the coast east of Exmouth Gulf and between 1838 and 1841 Captains Wickham and Stokes had discovered the mouth of the Ashburton River (Webb & Webb 1983:12). On 5th March 1839 Lieutenant George Grey came upon the mouth of the Gascoyne River and during his explorations encountered Aborigines. He reported that (Brown 1972:83): “they spoke a dialect very closely resembling that of the natives of the Swan River”. Further contact between Gascoyne-Ashburton language speakers and Europeans came in the 1850’s with inland explorations. In 1858 Francis Gregory explored the Gascoyne River and the Lyons River north as far as Mount Augustus (Green 1981:97-8, Webb & Webb 1983:11, Brown 1972:86). -

Many Words for Fire: an Etymological and Micromorphological Consideration of Combustion Features in Indigenous Archaeologicalsit

I. A. K. WardJournal & D. of E. the Friesem: Royal CombustionSociety of Western features Australia, in Indigenous 104: 11–24, archaeological 2021 sites Many words for fire: an etymological and micromorphological consideration of combustion features in Indigenous archaeological sites of Western Australia INGRID AK WARD 1* & DAVID E FRIESEM 2, 3 1 School of Social Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Crawley 6009, Australia 2 Recanatti Institute for Marine Studies, Department of Maritime Civilizations, School of Marine Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel 3 Haifa Center for Mediterranean History, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The word ‘fire’ encompasses an enormous variety of human activities and has diverse cultural meanings. The word hearth not only has links with fire but also has a social focus both in its Latin origins and in Australian Indigenous languages, where hearth fire is primary to all other anthropogenic fires. The importance of fire to First Nations people is reflected in the rich vocabulary of associated words, from different hearth types and fuel to the different purposes of fire in relation to cooking, medicine, ritual or management of the environment. Likewise, the archaeological expression of hearths and other combustion features is equally complex and nuanced, and can be explored on a microscale using micromorphology. Here we highlight the complexity in both language and micromorphological expressions around a range of documented and less well documented combustion features, including examples from archaeological sites in Western Australia. Our purpose is to discourage the over-use of the generalised term ‘hearth’ to describe charcoal and ash-rich features, and encourage a more nuanced study of the burnt record in a cultural context. -

What's in a Name? a Typological and Phylogenetic

What’s in a Name? A Typological and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Names of Pama-Nyungan Languages Katherine Rosenberg Advisor: Claire Bowern Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract The naming strategies used by Pama-Nyungan languages to refer to themselves show remarkably similar properties across the family. Names with similar mean- ings and constructions pop up across the family, even in languages that are not particularly closely related, such as Pitta Pitta and Mathi Mathi, which both feature reduplication, or Guwa and Kalaw Kawaw Ya which are both based on their respective words for ‘west.’ This variation within a closed set and similar- ity among related languages suggests the development of language names might be phylogenetic, as other aspects of historical linguistics have been shown to be; if this were the case, it would be possible to reconstruct the naming strategies used by the various ancestors of the Pama-Nyungan languages that are currently known. This is somewhat surprising, as names wouldn’t necessarily operate or develop in the same way as other aspects of language; this thesis seeks to de- termine whether it is indeed possible to analyze the names of Pama-Nyungan languages phylogenetically. In order to attempt such an analysis, however, it is necessary to have a principled classification system capable of capturing both the similarities and differences among various names. While people have noted some similarities and tendencies in Pama-Nyungan names before (McConvell 2006; Sutton 1979), no one has addressed this comprehensively. -

Native Title Information Handbook : Western Australia / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

Native Title Information Handbook Western Australia 2016 © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies AIATSIS acknowledges the funding support of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Native Title Research Unit (NTRU) acknowledges the generous contributions of peer reviewers and welcomes suggestions and comments about the content of the Native Title Information Handbook (the Handbook). The Handbook seeks to collate publicly available information about native title and related matters. The Handbook is intended as an introductory guide only and is not intended to be, nor should it be, relied upon as a substitute for legal or other professional advice. If you are aware that this publication contains any errors or omissions please contact us. Views expressed in the Handbook are not necessarily those of AIATSIS. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone 02 6261 4223 Fax 02 6249 7714 Email [email protected] Web www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Native title information handbook : Western Australia / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Native Title Research Unit. ISBN: 9781922102577 (ebook) Subjects: Native title (Australia)--Western Australia--Handbooks, manuals, etc. Aboriginal Australians--Land tenure--Western Australia. Land use--Law and legislation--Western Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Western Australia. Other Creators/Contributors: -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

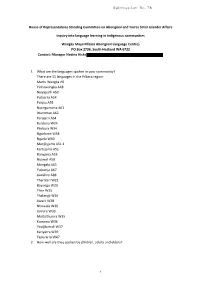

Submission No.78

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Inquiry into language learning in Indigenous communities Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre} PO Box 2736, South Hedland WA 6722 Contact: Manager Nadine Hicks 1. What are the languages spoken in your community? There are 31 languages in the Pilbara region: Martu Wangka A6 Yinhawangka A48 Nyiyaparli A50 Putijarra A54 Palyku A55 Nyangumarta A61 Warnman A62 Karajarri A64 Burduna W24 Pinikura W34 Ngarluma W38 Ngarla W40 Manjilyjarra A51.1 Kartujarra A51 Banyjima A53 Nyamal A58 Mangala A65 Yulparija A67 Juwaliny A88 Tharrkari W21 Bayungu W23 Thiin W25 Thalanyji W26 Jiwarli W28 Nhuwala W30 Jurruru W33 Martuthunira W35 Kurrama W36 Yindjibarndi W37 Kariyarra W39 Yapurarra W47 2. How well are they spoken by children, adults and elders? 1 This varies widely. While some languages such as Thiin are no longer spoken at all, others such as Martu Wangka are widely spoken by all age groups. Detailed information for each language is available on request. 3. Describe your group and project? Wangka Maya was begun by a group of Pilbara language speakers who were concerned at the loss of languages. It aims to record and foster the Aboriginal languages of the Pilbara region. The group began with no funding working as volunteers. Gradually they attracted project funding and eventually ongoing funding as a language centre. a) Why was it important to start up? Almost no work was being done to record or foster the use of local languages. b) How long have you been running? Since 1987 c) What age group(s) are you working with? All ages. -

Indigenous People and the Pilbara Mining Boom a Baseline for Regional Participation

Indigenous people and the Pilbara mining boom A baseline for regional participation J. Taylor and B. Scambary Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research The Australian National University, Canberra Research Monograph No. 25 2005 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication entry. Taylor, John, 1953 - Indigenous people and the Pilbara mining boom: A baseline for regional participation Bibliography ISBN 1 9209424 0 8 ISBN 1 9209425 4 8 (Online document) 1. Aboriginal Australians - Western Australia - Pilbara - Economic conditions. 2. Community development - Western Australia - Pilbara. 3. Sustainable development - Western Australia - Pilbara. 4. Mineral industries - Western Australia - Pilbara. 5. Pilbara (W.A.) - Economic conditions. I. Scambary, B. II. Australian National University. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. III. Title. (Series : Research monograph (Australian National University. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research) ; no. 25). 362.84991509413 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Brendon McKinley Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Table of Contents List of Figures v List of Tables vii Foreword xi Acknowledgements xiii A note on spellings of Aboriginal words xv Acronyms and abbreviations xvii 1. Profiling outcomes 1 Methods 4 Statistical geography 7 2. Demography of the Pilbara region 9 Population size 9 Population growth 13 Population distribution 14 Age composition 16 Population projections 18 3. -

Original Distribution of Trichosurus Vulpecula (Marsupialia: Phalangeridae) in Western Australia, with Particular Reference to Occurrence Outside the Southwest

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 95: 83–93, 2012 Original distribution of Trichosurus vulpecula (Marsupialia: Phalangeridae) in Western Australia, with particular reference to occurrence outside the southwest I ABBOTT Department of Environment and Conservation, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, WA 6983, Australia. ! [email protected] Trichosurus vulpecula, ‘common brushtail possum’, is currently considered to have never occurred in ~20% of Western Australia. This paper reports the results of a survey of historical sources, showing that the species was widely known to Aborigines and was once more broadly distributed, and may have occurred across almost all of Western Australia in 1829, the year of first settlement by Europeans. A remarkable contraction in geographical range commenced ca 1880, caused by an epizootic, and continued from ca 1920–1960 as a result of depredation by foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Some 220 Aboriginal names from outside the southwest were discovered. These are tabulated, and most can be reduced to seven regional names. Several or all of these names appear suitable for adoption into regional use in Western Australia. The current vernacular name is now inaccurate (the species is no longer common anywhere in Western Australia and is not closely related to the Virginia opossum, Didelphys virginiana, which belongs to a different family of marsupials), and should be replaced by one or more Aboriginal names. KEYWORDS: Aboriginal names, biogeography, brushtail possum, ecological history, mammal, regional extinction, Trichosurus vulpecula INTRODUCTION 1. Specimens held in the collection of the Western Australian Museum (Kitchener & Vicker 1981) Trichosurus vulpecula, known as the ‘common brushtail possum’ (Kerle & How 2008), until recent times occurred 2.