ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES of the GASCOYNE-ASHBURTON REGION Peter Austin 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bushfire Brigade Annual General Meeting

BUSHFIRE BRIGADE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AGENDA FOR THE SHIRE OF MINGENEW BUSHFIRE BRIGADES’ ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING TO BE HELD AT THE SHIRE CHAMBERS ON 25 MARCH 2019 COMMENCING AT 6PM. 1.0 DECLARATION OF OPENING 2.0 RECORD OF ATTENDANCE / APOLOGIES ATTENDEES To be confirmed APOLOGIES Vicki Booth – A/Area Officer – Fire Services Midwest (DFES) 3.0 CONFIRMATION OF PREVIOUS MEETING MINUTES 3.1 BUSHFIRE BRIGADES’ MEETING HELD 02 OCTOBER 2018 BRIGADES’ DECISION – ITEM 3.1 Moved: Seconded: That the minutes of the Bushfire Brigades’ Annual General Meeting of the Shire of Mingenew held 02 October 2018 be confirmed as a true and accurate record of proceedings. VOTING DETAILS: 4.0 OFFICERS REPORTS 4.1 Chief Bush Fire Control Officer Report- Murray Thomas • Overview of the 2018/19 Fire Season • Gazetted change in Shires Restricted Burning Times- now changed from the 17th September to the 1st October. All other timeframes remain the same (Prohibited- 1 Nov- 31 Jan, Restricted 1 October-15 March, open season 16 March- 30 September). This means that the CBFCO can now shorten or lengthen that new restricted date by 14 days depending on seasonal conditions (so restricted timeframe can potentially be pushed out to 17 September-31 October or shortened to 14 October-31 October). 4.2 Captains Reports- All Captains to remark on level of training of its volunteers and any identified gaps or training requirements. MINGENEW BUSHFIRE ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING AGENDA – 26 September 2017 4.2.1 Yandanooka 4.2.2 Lockier 4.2.3 Guranu 4.2.4 Mingenew North 4.2.5 Mingenew Town 4.3 Shire CEO Report • 2017/18 Operating Grant has been fully expended and acquitted. -

2014-09-16 QON Stock on Stations

16 SEP 2014 :...:_~,_.~~- . -'-~~--.•.•..""".;".",,- -~" LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ~ ~-..i Question on notice Wednesday, 13 August 2014 1447. Hon Robin Chapple to the Parliamentary Secretary representing the Minister for Lands. I refer to the Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia pastoral condition assessment reports, the Western Australian Rangeland Monitoring System (WARMS) and pastoral stations Binthalya, Boolathana, Brick House, Callagiddy, Callytharra Springs, Cardabia, Cooalya, Cooralya, Doorawarrah, Edaggee, Ellavalla, Gnaraloo, Hill Springs, Kennedy Range, Lyndon, Manberry, Mardathuna, Marrilla, Marron, Meedo, Meeragoolia, Mia Mia, Middalya, Minilya, Moogooree, Mooka, Pimbee, Quobba, Wahroonga, Wandagee, Warroora, Williambury, Winning, Wooramel, Woyyo, Yalbalgo, Yalobia and Yaringa, and I ask: (a) which of these stations are farming sheep; (b) which of these stations are farming Damara or Dorper species; (c) which of these stations are farming goats; (d) what are the estimated numbers of farmed animals on each station; (e) what is the estimated density of farmed animals on each station; (f) what are the latest pastoral condition assessment reports for these stations; (g) will the minister table the latest pastoral condition assessment reports for these stations; (h) if no to (g), why not; (i) are any of these stations subject to any changes in Range Land Condition Index reports; 0) are there any negative changes in rangeland conditions for the above stations; (k) if yes to 0), which stations; (I) is the Minister and -

What's New in Native Title

WHAT’S NEW IN NATIVE TITLE JUNE 2018 1. Case Summaries _______________________________________________ 1 2. Legislation ____________________________________________________ 9 3. Native Title Determinations _______________________________________ 9 4. Registered Native Title Bodies Corporate & Prescribed Bodies Corporate ___ 9 5. Indigenous Land Use Agreements _________________________________ 10 6. Future Act Determinations _______________________________________ 11 7. Publications __________________________________________________ 13 8. Training and Professional Development Opportunities _________________ 13 9. Events ______________________________________________________ 14 1. Case Summaries Quall v Northern Land Council [2018] FCA 989 29 June 2018, Practice and Procedure, Federal Court of Australia – Northern Territory, Reeves J In this matter the Court declared that the first respondent, the Northern Land Council (NLC), had not certified an application for the registration of the Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) in accordance with s 24CG(3)(a) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA), and in performance of its functions as a representative body under s 203BE(1)(b) of the NTA. The ILUA was dated 21 July 2016 and amended by a Deed of Variation dated 2 February 2017, known as the Kenbi ILUA. The Court ordered that the first respondent pay the applicant’s costs. The applicant was Mr Kevin Quall. The respondents to the claim were the Northern Land Council, and Joe Morrison as Chief Executive Officer of the Northern Land Council. The NLC had submitted a certification of the ILUA which was signed by Mr Joe Morrison, acting in his capacity as CEO of NLC. The issue was not with the contents of this agreement, but whether the CEO could validly sign the certification of the agreement and therefore meet the requirements of s 203 BE(1)(b) NTA. -

Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal Languages South of the Kimberley Region

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - 124 HANDBOOK OF WESTERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES SOUTH OF THE KIMBERLEY REGION Nicholas Thieberger Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Thieberger, N. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley Region. C-124, viii + 416 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1993. DOI:10.15144/PL-C124.cover ©1993 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES c: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W.Bender KA. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics DavidBradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University University of Adelaide S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin KL. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W.Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K T' sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. Uhlenbeck Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Leiden L.A. -

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia By: D.A. Cumming, D. Garratt, M. McCarthy, A. WoICe With <.:unlribuliuns from Albany Seniur High Schoul. M. Anderson. R. Howard. C.A. Miller and P. Worsley Octobel' 1995 @WAUUSEUM Report: Department of Matitime Archaeology, Westem Australian Maritime Museum. No, 98. Cover pholograph: A view of Halllelin Bay in iL~ heyday as a limber porl. (W A Marilime Museum) This study is dedicated to the memory of Denis Arthur Cuml11ing 1923-1995 This project was funded under the National Estate Program, a Commonwealth-financed grants scheme administered by the Australian HeriL:'lge Commission (Federal Government) and the Heritage Council of Western Australia. (State Govenlluent). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Heritage Council of Western Australia Mr lan Baxter (Director) Mr Geny MacGill Ms Jenni Williams Ms Sharon McKerrow Dr Lenore Layman The Institution of Engineers, Australia Mr Max Anderson Mr Richard Hartley Mr Bmce James Mr Tony Moulds Mrs Dorothy Austen-Smith The State Archive of Westem Australia Mr David Whitford The Esperance Bay HistOIical Society Mrs Olive Tamlin Mr Merv Andre Mr Peter Anderson of Esperance Mr Peter Hudson of Esperance The Augusta HistOIical Society Mr Steve Mm'shall of Augusta The Busselton HistOlical Societv Mrs Elizabeth Nelson Mr Alfred Reynolds of Dunsborough Mr Philip Overton of Busselton Mr Rupert Genitsen The Bunbury Timber Jetty Preservation Society inc. Mrs B. Manea The Bunbury HistOlical Society The Rockingham Historical Society The Geraldton Historical Society Mrs J Trautman Mrs D Benzie Mrs Glenis Thomas Mr Peter W orsley of Gerald ton The Onslow Goods Shed Museum Mr lan Blair Mr Les Butcher Ms Gaye Nay ton The Roebourne Historical Society. -

A Grammatical Sketch of Ngarla: a Language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY master thesis The department for linguistics and philology spring term 2007 A grammatical sketch of Ngarla: A language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund Supervisor: Anju Saxena Abstract In this thesis the basic grammatical structure of normal speech style of the Western Australian language Ngarla is described using example sentences taken from the Ngarla – English Dictionary (by Geytenbeek; unpublished). No previous description of the language exists, and since there are only five people who still speak it, it is of utmost importance that it is investigated and described. The analysis in this thesis has been made by Torbjörn Westerlund, and the focus lies on the morphology of the nominal word class. The preliminary results show that the language shares many grammatical traits with other Australian languages, e.g. the ergative/absolutive case marking pattern. The language also appears to have an extensive verbal inflectional system, and many verbalisers. 2 Abbreviations 0 zero marked morpheme 1 first person 1DU first person dual 1PL first person plural 1SG first person singular 2 second person 2DU second person dual 2PL second person plural 2SG second person singular 3 third person 3DU third person dual 3PL third person plural 3SG third person singular A the transitive subject ABL ablative ACC accusative ALL/ALL2 allative ASP aspect marker BUFF buffer morpheme C consonant CAUS causative COM comitative DAT dative DEM demonstrative DU dual EMPH emphatic marker ERG ergative EXCL exclusive, excluding addressee FACT factitive FUT future tense HORT hortative ImmPAST immediate past IMP imperative INCHO inchoative INCL inclusive, including addressee INSTR instrumental LOC locative NEG negation NMLISER nominaliser NOM nominative N.SUFF nominal class suffix OBSCRD obscured perception P the transitive object p.c. -

Barque Stefano Shipwreck Early NW Talandji Ngarluma Aboriginal

[IV] SOME EARLY NORTH WEST INDIGENOUS WORDLISTS Josko Petkovic They spoke a language close to Talandji and were sometimes considered only to be western Talandji, but informants were sure that they had separate identities for a long time. Norman B.Tindale1 The indigenous words in the Stefano manuscript give us an important albeit small window into the languages of the North West Cape Aborigines.2 From the available information, we can now be reasonably certain that this wordlist belongs primarily to the Yinikurtira language group.3 We also know that the Yinikurtira community came to be dispersed about one hundred years ago and its members ceased using the Yinikuritra language, which is now formally designated as extinct.4 If in these circumstances we want to find something authentic about the Yinikurtira language we cannot do so by simply asking one of its living speakers. Rather, we need to look at the documents on the Yinikurtira language and culture from about a century ago and from the time when the Yinikurtira people were still living on Yinikurtira country. The documentation we have on the Yinikurtira people comes primarily from Tom Carter, who lived among the Yinikurtira community for about thirteen years.5 Carter left an extensive collection of indigenous bird names and through Daisy Bates he left a considerable vocabulary of Yinikurtira words.6 In his diaries there is an enigmatic paragraph on the languages of the North West Cape region, in which he differentiates the languages north and south of the Gascoyne River, while also invoking a commonality of languages north of the Gascoyne River: The natives of the Gascoyne Lower River were of the Inggarda tribe and spoke a quite different language from By-oong tribe of the Minilya River, only eight miles distant. -

![AR Radcliffe-Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4080/ar-radcliffe-brown-684080.webp)

AR Radcliffe-Brown]

P129: The Personal Archives of Alfred Reginald RADCLIFFE-BROWN (1881- 1955), Professor of Anthropology 1926 – 1931 Contents Date Range: 1915-1951 Shelf Metre: 0.16 Accession: Series 2: Gift and deposit register p162 Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was born on 17 January 1881 at Aston, Warwickshire, England, second son of Alfred Brown, manufacturer's clerk and his wife Hannah, nee Radcliffe. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A. 1905, M. A. 1909), graduating with first class honours in the moral sciences tripos. He studied psychology under W. H. R. Rivers, who, with A. C. Haddon, led him towards social anthropology. Elected Anthony Wilkin student in ethnology in 1906 (and 1909), he spent two years in the field in the Andaman Islands. A fellow of Trinity (1908 - 1914), he lectured twice a week on ethnology at the London School of Economics and visited Paris where he met Emily Durkheim. At Cambridge on 19 April 1910 he married Winifred Marie Lyon; they were divorced in 1938. Radcliffe-Brown (then known as AR Brown) joined E. L. Grant Watson and Daisy Bates in an expedition to the North-West of Western Australia studying the remnants of Aboriginal tribes for some two years from 1910, but friction developed between Brown and Mrs. Bates. Brown published his research from that time in an article titled “Three Tribes of Western Australia”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 43, (Jan. - Jun., 1913), pp. 143-194. At the 1914 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Melbourne, Daisy Bates accused Brown of gross plagiarism. -

Pilbara–Gascoyne

Pilbara–Gascoyne 11 Pilbara–Gascoyne ...................................................... 2 11.5 Surface water and groundwater ....................... 26 11.1 Introduction ........................................................ 2 11.5.1 Rivers ................................................... 26 11.2 Key information .................................................. 3 11.5.2 Flooding ............................................... 26 11.3 Description of the region .................................. 4 11.5.3 Storage systems ................................... 26 11.3.1 Physiographic characteristics.................. 6 11.5.4 Wetlands .............................................. 26 11.3.2 Elevation ................................................. 7 11.5.5 Hydrogeology ....................................... 30 11.3.3 Slopes .................................................... 8 11.5.6 Water table salinity ................................ 30 11.3.4 Soil types ............................................... 9 11.5.7 Groundwater management units ........... 30 11.3.5 Land use ............................................. 11 11.6 Water for cities and towns ............................... 34 11.3.6 Population distribution .......................... 13 11.6.1 Urban centres ....................................... 34 11.3.7 Rainfall zones ....................................... 14 11.6.2 Sources of water supply ....................... 34 11.3.8 Rainfall deficit ....................................... 15 11.6.3 Geraldton ............................................ -

20131118 DBNGP EP Public Summary Document

Dampier to Bunbury Natural Gas Pipeline ENVIRONMENT PLAN REVISION 5.2 SUMMARY DOCUMENT NOVEMBER 2013 DBNGP Environment Plan Revision 5.2 Summary Document DOCUMENT CONTROL Rev Date Description 0 18/11/13 Document created for the DBNGP EP Revision 5.2 Title Name Author Senior Advisor – Environment and Heritage L Watson Reviewed Manager - Health Safety and Environment D Ferguson Approved General Manager - Corporate Services A Cribb 2 DBNGP Environment Plan Revision 5.2 Summary Document Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Proponent ...................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Location ......................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Existing Environment ................................................................................................................... 4 4.1. Pilbara Region .......................................................................................................................... 7 4.2. Carnarvon Region .................................................................................................................... 7 4.3. Gascoyne Region ..................................................................................................................... 8 4.4. Yalgoo Region ......................................................................................................................... -

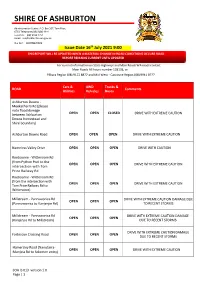

SOA IS 013 Version 1.0 Page | 1 Hamersley Road (Solomon Entry OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE with EXTREME CAUTION to Rio Rail Access Road)

SHIRE OF ASHBURTON Administration Centre. P.O. Box 567, Tom Price, 6751 Telephone (08) 9188 4444 Facsimile (08) 9189 2252 Email: [email protected] Our Ref: 1847898/RD09 Issue Date 16th July 2021 9:00 THIS REPORT WILL BE UPDATED WHEN A MATERIAL CHANGE IN ROAD CONDITIONS OCCURS ROAD REPORT REMAINS CURRENT UNTIL UPDATED For current information on State Highways and Main Roads WA roads contact Main Roads All hours number 138138, or Pilbara Region (08) 9172 8877 and Mid West - Gascoyne Region (08) 9941 0777 Cars & 4WD Trucks & ROAD Comments Utilities Vehicles Buses Ashburton Downs - Meekatharra Rd (please note flood damage between Ashburton OPEN OPEN CLOSED DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION Downs homestead and Shire boundary) Ashburton Downs Road OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION Nameless Valley Drive OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE WITH CAUTION Roebourne - Wittenoom Rd (from Python Pool to the OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION intersection with Tom Price Railway Rd Roebourne - Wittenoom Rd (from the intersection with OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION Tom Price Railway Rd to Wittenoom) Millstream - Pannawonica Rd DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION DAMAGE DUE OPEN OPEN OPEN (Pannawonica to Kanjenjie Rd) TO RECENT STORMS Millstream - Pannawonica Rd DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION DAMAGE OPEN OPEN OPEN (Kanjenjie Rd to Millstream) DUE TO RECENT STORMS DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION DAMAGE Fortescue Crossing Road OPEN OPEN OPEN DUE TO RECENT STORMS Hamersley Road (Nanutarra- OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION Munjina Rd to Solomon entry) SOA -

Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Recreational Use at Ningaloo Reef

Spatial and temporal patterns of recreational use at Ningaloo Reef, north-western Australia This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Environmental Science, Murdoch University 2009 Claire B. Smallwood BSc (Hons) DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary educational institution. _________________ ______________ Claire B. Smallwood Date Abstract Worldwide, studies of recreational use at fine temporal and spatial scales within marine protected areas are rare, even though this knowledge is essential for successful management with respect to biodiversity conservation, resource allocation and visitor experiences. Ningaloo, a diverse fringing coral reef extending 300 km along the coast of north-western Australia, is reserved as a multiple use marine park. Its isolation from major population centres and limited access has, until recently, shielded it from extensive tourism. However, a growing population and increased publicity have led to a growth in visitor numbers and development pressure. This study aimed to map the fine- scale patterns of recreation at Ningaloo over a 12-month period using a multi-faceted survey approach which recorded >40 000 people. Synoptic patterns were described from 34 aerial surveys, while specific activities (e.g. recreational line fishing, snorkelling and windsurfing) were characterised using 192 land-based coastal surveys. During peak months from April to October, spatial distribution and density of use increased by up to 50% and included expansion of boating activity beyond the sheltered lagoon environment. Sandy beaches were preferred sites for recreation and people were generally clustered around infrastructure such as boat ramps and camping sites.