Downloaded 3/1/16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Euphorbia Subg

ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЕ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ БЮДЖЕТНОЕ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ НАУКИ БОТАНИЧЕСКИЙ ИНСТИТУТ ИМ. В.Л. КОМАРОВА РОССИЙСКОЙ АКАДЕМИИ НАУК На правах рукописи Гельтман Дмитрий Викторович ПОДРОД ESULA РОДА EUPHORBIA (EUPHORBIACEAE): СИСТЕМА, ФИЛОГЕНИЯ, ГЕОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ АНАЛИЗ 03.02.01 — ботаника ДИССЕРТАЦИЯ на соискание ученой степени доктора биологических наук САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ 2015 2 Оглавление Введение ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Глава 1. Род Euphorbia и основные проблемы его систематики ......................................... 9 1.1. Общая характеристика и систематическое положение .......................................... 9 1.2. Краткая история таксономического изучения и формирования системы рода ... 10 1.3. Основные проблемы систематики рода Euphorbia и его подрода Esula на рубеже XX–XXI вв. и пути их решения ..................................................................................... 15 Глава 2. Материал и методы исследования ........................................................................... 17 Глава 3. Построение системы подрода Esula рода Euphorbia на основе молекулярно- филогенетического подхода ...................................................................................................... 24 3.1. Краткая история молекулярно-филогенетического изучения рода Euphorbia и его подрода Esula ......................................................................................................... 24 3.2. Результаты молекулярно-филогенетического -

Myrtle Spurge: Options for Control the Myrtle Spurge, a Class-B Non Desig- the Other Is on Hwy

Myrtle Spurge: Options for Control The myrtle spurge, a class-B non desig- the other is on Hwy. 28 in Odessa. nate noxious weed in Lincoln County, Wash- Myrtle spurge is poisonous if ingested, ington (Euphorbia myrsinites), also known as causing nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. This creeping spurge or donkey tail, and is a suc- plant exudes toxic, milky latex, which can cause culent species of spurges (family Eu- severe skin and eye irritations. Wearing phorbiaceae). Introduced here from gloves, long sleeves, and shoes is highly the Mediterranean region, it is a per- recommended when in contact with ennial forb. It prefers full sun, well Myrtle spurge, as all plant parts are con- drained soil and is found in gardens, sidered poisonous. Although some- natural areas and rocky slopes. Myr- times grown as a decorative plant in tle spurge was added to the Lincoln xeric gardens, myrtle spurge is consid- County ered highly invasive and noxious. This Noxious Weed List plant can rapidly ex- in 2006, after being pand into sensitive eco- discovered in two systems, displacing na- locations. One at tive vegetation and re- Rantz Marina on ducing forage for wild- Lake Roosevelt and life. Key identifying traits • Inconspicuous yellow-green flowers are sur- A close-up of the Myrtle Spurge heart shaped bracts. rounded by heart shaped bracts. Myrtle Spurge is commonly • Plants can grow 8-12 inches tall on ascending found in rock gardens. to trailing stems rising at the tips. • Oval, blue-green, fleshy, succulent-like leaves are arranged in close spirals around the stems. • Stems grow from a prostrate woody base. -

Botanischer Garten Der Universität Tübingen

Botanischer Garten der Universität Tübingen 1974 – 2008 2 System FRANZ OBERWINKLER Emeritus für Spezielle Botanik und Mykologie Ehemaliger Direktor des Botanischen Gartens 2016 2016 zur Erinnerung an LEONHART FUCHS (1501-1566), 450. Todesjahr 40 Jahre Alpenpflanzen-Lehrpfad am Iseler, Oberjoch, ab 1976 20 Jahre Förderkreis Botanischer Garten der Universität Tübingen, ab 1996 für alle, die im Garten gearbeitet und nachgedacht haben 2 Inhalt Vorwort ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Baupläne und Funktionen der Blüten ......................................................................................... 9 Hierarchie der Taxa .................................................................................................................. 13 Systeme der Bedecktsamer, Magnoliophytina ......................................................................... 15 Das System von ANTOINE-LAURENT DE JUSSIEU ................................................................. 16 Das System von AUGUST EICHLER ....................................................................................... 17 Das System von ADOLF ENGLER .......................................................................................... 19 Das System von ARMEN TAKHTAJAN ................................................................................... 21 Das System nach molekularen Phylogenien ........................................................................ 22 -

Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan: US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area, El Paso County, CO

Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area August 2015 CNHP’s mission is to preserve the natural diversity of life by contributing the essential scientific foundation that leads to lasting conservation of Colorado's biological wealth. Colorado Natural Heritage Program Warner College of Natural Resources Colorado State University 1475 Campus Delivery Fort Collins, CO 80523 (970) 491-7331 Report Prepared for: United States Air Force Academy Department of Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Smith, P., S. S. Panjabi, and J. Handwerk. 2015. Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan: US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area, El Paso County, CO. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado. Front Cover: Documenting weeds at the US Air Force Academy. Photos courtesy of the Colorado Natural Heritage Program © Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area El Paso County, CO Pam Smith, Susan Spackman Panjabi, and Jill Handwerk Colorado Natural Heritage Program Warner College of Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 August 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Various federal, state, and local laws, ordinances, orders, and policies require land managers to control noxious weeds. The purpose of this plan is to provide a guide to manage, in the most efficient and effective manner, the noxious weeds on the US Air Force Academy (Academy) and Farish Recreation Area (Farish) over the next 10 years (through 2025), in accordance with their respective integrated natural resources management plans. This plan pertains to the “natural” portions of the Academy and excludes highly developed areas, such as around buildings, recreation fields, and lawns. -

Plant Species to AVOID for Landscaping, Revegetation, and Restoration Colorado Native Plant Society Revised by the Horticulture and Restoration Committee, May, 2002

Plant Species to AVOID for Landscaping, Revegetation, and Restoration Colorado Native Plant Society Revised by the Horticulture and Restoration Committee, May, 2002 The plants listed below are invasive exotic species which threaten or potentially threaten natural areas, agricultural lands, and gardens. This is a working list of species which have escaped from landscaping, reclamation projects, and agricultural activity. All problem plants may not be included; contact the Colorado Dept. of Agriculture for more information (see references below). Some drought resistent, well adapted exotic plants suggested for landscaping survive successfully outside cultivation. If you are unsure about introducing a new plant into your garden or reclamation/restoration plans, maintain a conservative approach. Try to research a new plant thoroughly before using it, or omit it from your plans. While there are thousands of introduced plants which pose no threats, there are some that become invasive, displacing and outcompeting native vegetation, and cost land managers time and money to deal with. If you introduce a plant and notice it becoming aggressive and invasive, remove it and report your experience to us, your county extension agent, and the grower. If you see a plant for sale that is listed on the Colorado Noxious Weed List, please report it to the CO Dept. of Ag. (Jerry Cochran, Nursery Specialist; 303.239.4153). This list will be updated periodically as new information is received. For more information, including a list of suggested native plants for horticultural use, and to contact us, please visit our website at www.conps.org. NOX NE & NRCS INV RMNP WISC CA CoNPS CD PCA UM COMMENTS COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME* (CO) GP INVASIVE EXOTIC FORBS – Often found in seed mixes or nurseries Baby's breath Gypsophila paniculata X X X X NATIVE ALTERNATIVES: Native penstemon Saponaria officinalis (Lychnis (Penstemon spp.); Rocky Mtn Beeplant (Cleome Bouncing bet, soapwort X X X X X saponaria) serrulata); Native white yarrow (Achillea lanulosa). -

Working List of Invasive Vascular Plants of Wyoming ─ III (Vernacular Names from Selected Major Works) Dec 2017

Working List of Invasive Vascular Plants of Wyoming ─ III (Vernacular names from selected major works) Dec 2017 Compiled by R.L. Hartman and B.E. Nelson With assistance from R.D. Dorn, W. Fertig, B. Heidel The following list contains 372 taxa introduced to Wyoming from outside North America; included are invasives recognized by the Wyoming state government as noxious (; 28; although Ambrosa tomentosa is native). A number of these species repesent escapes from cultivation and are limited to one or a few collections. Nomenclature is based on R.D. Dorn, 2001, Vascular Plants of Wyoming; where updated, Dorn’s synonyms are in square brackets [ ]. Other synonyms found in the list of sources below are not included. Likewise, family names and their circumscriptions follow Dorn; where defined differently by the Angiosperm Working Group IV (APG IV), clarification follows in parenthese. Dorn does not indicate the typical variety or subspecies unless a second infraspecific taxon is recognized. We have included the typical infraspecies where appropriate. The lack of hyphenation, word separation, or capitalization may not reflect the appearance of the vernacular names in the works cited. Sources for vernacular names: 1 Weed Science Society of America. 2010. Composite List of Weeds. 2 Kartesz, J.T., The Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2015. Taxonomic Data Center. 3 P. Rice. 2000. Invaders Database System. Univ. of Montana. Release 14 Feb 2000 (not available for update). 4 Flora of the Great Plains Association. 1986. Flora of the Great Plains. Univ. Oklahoma Press. 5 C.L. Hitchcock & A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest. -

10 Years of Conservation Science on the Zumwalt Prairie

10 YEARS OF CONSERVATION SCIENCE ON THE ZUMWALT PRAIRIE What Have We Learned? Geographically isolated and comprised mostly of private lands, scant scientific information exists regarding the soils, vegetation, wildlife and ecology of the Zumwalt Prairie. Science is at the core of the Nature Conservancy’s conservation approach and soon after the Conservancy acquired the Zumwalt Prairie Preserve in 2000, the organization recognized the need to support scientific inquiry into the prairie’s ecology and how human actions such as livestock grazing, fire, and invasive species affect it. Beginning with a study of the prairie’s raptor populations in 2003, the Conservancy has collaborated with universities and agencies for over ten years in its quest to find answers to key conservation questions. Over 10 published papers, dozens of reports and presentations have resulted in these efforts, broadening our knowledge of the biodiversity and ecological processes of the Zumwalt and informing stewardship and other conservation actions. Conservancy staff also serve on technical advisory groups, review boards, and in other roles to promote scientific inquiry and communication of information to landowners and other stakeholders. Short summaries of findings resulting from Zumwalt Science efforts are summarized below. For more information contact Rob Taylor ([email protected]). Many of the reports, lists, and publications cited here can be found on the Conservation Gateway at: https://www.conservationgateway.org/ConservationByGeography/NorthAmerica/UnitedStates/oregon/grasslands/zumwalt BIODIVERSITY While no formal “bio blitz” has ever been undertaken on the Zumwalt Prairie, various inventory, monitoring and research projects have contributed to our understanding of the biodiversity that inhabits this extraordinary grassland ecosystem. -

Going to Sustainable

GOING TO SUSTAINABLE Lowering Landscape and Garden Maintenance Including Better Ways to Water and How to Save Water © Joseph L. Seals, 2008, 2009 Copyright Joseph L. Seals, 2008, 2009 LOWERING MAINTENANCE REDUCING MAINTENANCE IN THE PLANNING STAGES Unfortunately, maintenance of the landscape is often assumed or overlooked during the planning and design phase of a project 1) Keep the planting design simple. The more elaborate the plan and planting -- Numbers of plants, variety of plants, -- less than simple lines and shapes -- … the more maintenance is required. For instance, lawn areas need to be plotted so that mowing, edging and periodic maintenance can be accomplished easily. -- Avoid tight angles and sharp corners. -- wide angles, gentle, sweeping curves, and straight lines are much easier to mow. -- Make certain each plant in the plan serves a purpose. 2) Select the right plant for the right place We all know that there are “sun plants” for sunny spots and “shade plants” for shady spots. And we don’t plant “sun plants” in shade nor do we plant “shade plants” in sun. And some of us know that there are drought-tolerant plants that like dry soil and little water -- and there are moisture-loving plants that like their feet wet. And we don’t mix those up either. Such “mix ups” result in everything from the obvious: outright death of the plant involved to a subtly stressed plant that shows various symptoms of “disease” -- whether it’s an actual organism or a physiological condition. Copyright Joseph L. Seals, 2008, 2009 Every time you push a plant beyond its natural adaptations, abilities, and tolerances, you invite problems and you invite higher maintenance When choosing the right plant, start with THE BIG PICTURE: We have a Mediterranean climate. -

Comparative Anatomical Study on Leaves of Three Euphorbia L. Species Rodica Bercu & Dan Răzvan Popoviciu

© Landesmuseum für Kärnten; download www.landesmuseum.ktn.gv.at/wulfenia; www.zobodat.at Wulfenia 22 (2015): 271–276 Mitteilungen des Kärntner Botanikzentrums Klagenfurt Comparative anatomical study on leaves of three Euphorbia L. species Rodica Bercu & Dan Răzvan Popoviciu Summary: The paper presents a comparative study on the leaf structure of three species belonging to Euphorbiaceae: Euphorbia myrsinites, E. nicaeensis subsp. dobrogensis and E. seguieriana. Anatomically, the leaves of the three species are relatively similar in their basic structure. However, differences appear regarding epidermal cells and cuticular papillae, mesophyll, density of stomata and type of stomatal complex, laticifers and development of the vascular system. Keywords: comparative anatomy, laticifers, leaves, stomata, Euphorbia Euphorbiaceae is the sixth largest plant family comprising 322 genera and about 8910 species, most common in the humid tropical and subtropical regions of both hemispheres (Webster 1987). Many species are commonly known as spurges (Radcliffe-Smith 1987 ). Euphorbia myrsinites L., also known as myrtle spurge, creeping spurge or donkey tail, is a perennial, herbaceous plant with sprawling stems growing up to 20 – 40 cm. The leaves are spirally arranged, fleshy, pale, glaucous, blueish-green, 1–2 cm long. The flowers are inconspicuous, but surrounded by bright sulphurous-yellow bracts (tinged red). They are flowering in spring. In the Romanian flora,Euphorbia myrsinites is considered as an endangered species (Dihoru & Negrean 2009). Euphorbia nicaeensis subsp. dobrogensis (Prodán) Kuzmanov is a herbaceous perennial, pale green, with hairless stems growing up to 40 cm, densely-foliated and branched at the top. The leaves are spirally arranged, 30 – 60 mm long and 15 –20 mm wide, elliptical in shape, obtuse on top and shortly mucronated. -

Noxious Weed Management Plan

WEED MANAGEMENT PLAN Asotin County Noxious Weed Control Board P.O. Box 881 Asotin, WA 99402 (509) 243-2098 Table of Contents I General Information Page - Introduction 3 - Asotin County Noxious Weed Control Board 3 - Weed Board Philosophy 4 - Goal 4 - Mission Statement 4 - Local Land Management Agencies 5 - Services, Materials and Information 5 - Board Meetings 5 - Weed Control Districts 6 - District Map 7 - Ongoing Projects 8,9 II Noxious Weeds Page - Bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare) 11 - Canada thistle ( Cirsium arvense) 14 - Dalmatian toadflax (Linaria dalmatica) 17 - Field bindweed ( Convolvulus arvensis) 21 - Hawkweeds spp ( Hieracium spp) 24 - Houndstongue ( Cynoglossum officinale ) 27 - Jointed goatgrass ( Aegilops cylindrical) 30 - Kochia ( Kochia scoparia ) 32 - Leafy spurge ( Euphorbia escula L .) 34 - Mediterranean sage ( Salvia aethiopis L.) 36 - Myrtle spurge ( Euphorbia myrsinites) 38 - Oxeye daisy ( Chrysanthemum leucanthemum ) 40 - Poison hemlock ( Conium maculatum ) 42 - Puncturevine ( Tribulus terrestris ) 45 - Rush skeletonweed ( Chonddrilla juncea L.) 48 - Russian knapweed ( Acroptilon repens ) 51 - Saltcedar ( Tamarix ramosissima ) 54 - Scotch thistle ( Onopordum acanthium ) 56 - Spotted knapweed and Diffuse knapweed - (Centaurea maculosa; C. diffusa ) 59 - St. Johnswort ( Hypericum perforatum ) 63 - Sulfur cinquefoil ( Potentilla recta L.) 65 - Whitetop ( Cardaria draba, C. pubescens ) 67 - Yellow starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis) 70 III Literature Cited 74 Introduction This handbook is designed to be a quick and easy resource guide for land owners and managers in Asotin County, Washington. It is expected to promote better and faster identification of problem weeds and to disseminate knowledge concerning various control practices. This Weed Management Plan should be considered a “work in progress”. Pages for additional weeds will be added from time to time. -

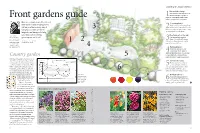

Front Gardens Guide Softens the Visual Impact

planting & design solutions Bin and bike storage This should be easily accessible from 1the house and gate. A green roof Front gardens guide softens the visual impact. Planted with sedums, it requires little maintenance. Even keen gardeners often spend Doorstep planter little time on their front gardens – Instead of using the doorstep planter yet we use them every day of 2 to hide the door key, make more of it. 3 It’s the perfect place to have a moveable feast the year. So here are three of seasonal bulbs or tender plants. inspirational designs to help you make a welcoming Plant support on the wall Annie Guilfoyle runs garden design green space out front Conventional trellis can look consultancy Creative dreary. This metal wall sculpture Landscapes (www. 3 Words & illustrations 2 adds individuality and provides a stylish creative-landscapes. ANNIE GUILFOYLE 1 com) and is director support for a beautiful rose. of garden design for KLC School of Design. 4 Ramped paving New-build dwellings should 4 comply with DDA regulations (Disability Discriminations Act), allowing Country garden 5 for wheelchair access. Ensure that the ramp is non-slip by using textured stone. When designing gardens, inspiration can be drawn from everything around you. In this Directional paving country garden two of my favourite influences Use diamond-sawn sandstone combine, with dashes of the garden at Great 5 cut in long lengths rather than Dixter in East Sussex meeting the sublime rectangles. Change the direction of the 1950s textile designs of Lucienne Day. Not 6 paving or vary the width to create a for the faint-hearted, as the colours are bold subtle effect without looking too fussy. -

Plants for a 'Sustainable” -- Low Maintenance – Garden and Landscape in Arroyo Grande

PLANTS FOR A ‘SUSTAINABLE” -- LOW MAINTENANCE – GARDEN AND LANDSCAPE IN ARROYO GRANDE Low water use, minimal fertilizer needs, no special care Large Trees -- Cedrus libanii atlantica ‘Glauca’ BLUE ATLAS CEDAR Cedrus deodara DEODAR CEDAR Cinnamomum camphora CAMPHOR Gingko biloba GINGKO Pinus canariensis CANARY ISLAND PINE Pinus pinea ITALIAN STONE PINE Pinus sabiniana GRAY PINE Pinus torreyana TORREY PINE Quercus ilex HOLLY OAK Quercus suber CORK OAK Medium Trees -- Allocasuarina verticillata SHE-OAK Arbutus ‘Marina’ HYBRID STRAWBERRY TREE Brachychiton populneus KURRAJONG, AUSTRALIAN BOTTLE TREE Brahea armata BLUE HESPER PALM Butia capitata PINDO PALM Eucalyptus nicholii PEPPERMINT GUM Eucalyptus polyanthemos SILVER DOLLAR GUM Calocedrus decurrens INCENSE CEDAR Cupressus arizonica ARIZONA CYPRESS Cupressus forbesii TECATE CYPRESS Geijera parviflora AUSTRALIAN WILLOW Gleditsia triacanthos inermis THORNLESS HONEY LOCUST Juniperus scopulorum ‘Tolleson’s Blue Weeping’ BLUE WEEPING JUNIPER Melaleuca linariifolia FLAXLEAF PAPERBARK Metrosideros excelsus NEW ZEALAND CHRISTMAS TREE Olea europaea OLIVE (only fruitless cultivars such as ‘Majestic Beauty’, ‘Wilsoni’) Pinus halepensis ALEPPO PINE Pistacia chinensis CHINESE PISTACHE Quercus chrysolepis CANYON LIVE OAK Sequoiadendron giganteum GIANT REDWOOD © Copyright Joe Seals 2009 Small Trees Acacia baileyana BAILEY’S ACACIA Acacia pendula WEEPING MYALL Celtis australis EUROPEAN HACKBERRY x Chiltalpa tashkentensis CHILTALPA Cordyline australis CABBAGE PALM Cotinus coggygria SMOKE TREE Eucalyptus