Volume 40 2013 Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carrying Forward Cabinda's Legacy of Progress

South China Morning Post SPECIAL REPORT INSIDE EIGHT-PAGE SPONSORED SECTION IN CO-OPERATION WITH ASIA BUSINESS UNIT LTD. AT A As economic development begins to take off in earnest in this GLANCE northern Angolan province, and as its oil production is stepped up, it is clear that this is the right moment for China to explore and enhance its relations with and participation in Cabinda CabindaFor further information contact: 1-7 Harley Street, London W1G 9QD - Tel: +44 207 291 4402 - Fax: +44 207 636 8789 - [email protected] - www.asiabusinessunit.com Carrying forward Oil-rich Angola grows Cabinda’s legacy LOCATION: of progress An enclave of Angola, separated from the stronger and more stable CABINDA’S PROVINCIAL Gover- province, in which its consid- mainland by the nor, Mawete João Baptista, erable mineral wealth is now Democratic Republic of has been on the job since No- being used to improve the Congo and the Congo vember, 2009, and has spent lives of the region’s people. In River the time since he moved into the time since the agreement the position getting to know was signed, Cabinda has CAPITAL: each and every day the region, its local leaders, made great strides in that di- Cabinda City and the problems that need to rection, but more must be POPULATION: ANGOLA has the potential to be one be dealt with to continue the done and Cabindans need to Approximately of Africa’s richest, most successful work of improving the lives of do their part with a feeling of 300,000, of which half countries. -

Angola Background Paper

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM ANGOLA UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, APRIL 1999 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY INFORMATION UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. PREFACE Angola has been an important source country of refugees and asylum-seekers over a number of years. This paper seeks to define the scope, destination, and causes of their flight. The first and second part of the paper contains information regarding the conditions in the country of origin, which are often invoked by asylum-seekers when submitting their claim for refugee status. The Country Information Unit of UNHCR's Centre for Documentation and Research (CDR) conducts its work on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment, with all sources cited. In the third part, the paper provides a statistical overview of refugees and asylum-seekers from Angola in the main European asylum countries, describing current trends in the number and origin of asylum requests as well as the results of their status determination. The data are derived from government statistics made available to UNHCR and are compiled by its Statistical Unit. Table of Contents 1. -

Economic and Social Development of Angola Due to Petroleum Exploration

XVII INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING AND OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT Technological Innovation and Intellectual Property: Production Engineering Challenges in Brazil Consolidation in the World Economic Scenario. Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 04 to 07 October – 2011 ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OF ANGOLA DUE TO PETROLEUM EXPLORATION DANIELLE FERNANDES DO CARMO (UFRJ) [email protected] The evaluation regarding the influence of petroleum production and exploration in a country is essential for a better usage of all the returns this commodity may generate. This article aims to explicit the current social and economic condittions of Angola in order to demonstrate if the country has improved its quality of life due to petroleum and gas exploration in the territory. The innumerable variables to be analyzed in this approach are: social and economic indices; and historic of the country’s development, which are divided into Human Development Index (HDI), Human Poverty Index (HPI), Child Mortality Rate, among others. Concerning the economic development of Angola, current economic indices will be applied, such as the Gross Domestic Product, daily production of oil and natural gas, oil and gas reserves which have been proved, among several others. This juxtaposition of social and economic indices will enable the evaluation of influences which Angola presents due to its insertion in the petroleum and gas production. It was concluded that petroleum and gas do not generate an even income distribution, however, they upgrade the country ratings in some social indicators (HDI, for example). Palavras-chaves: Petroleum and gas; Angola; quality of life; economic development. XVII INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING AND OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT Technological Innovation and Intellectual Property: Production Engineering Challenges in Brazil Consolidation in the World Economic Scenario. -

Angola Cabinda

Armed Conflicts Report - Angola Cabinda Armed Conflicts Report Angola-Cabinda (1994 - first combat deaths) Update: January 2007 Summary Type of Conflict Parties to the Conflict Status of the Fighting Number of Deaths Political Developments Background Arms Sources Economic Factors Summary: 2006 The Angolan government signed the Memorandum of Understanding in July 2006, a peace agreement with one faction of the rebel group FLEC (Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave). Because of this, and few reported conflict related deaths over the past two years (less than 25 per year), this armed conflict is now deemed to have ended. 2005 Government troops and rebels clashed on several occasions and the Angolan army continued to be accused of human rights abuses in the region. Over 50,000 refugees returned to Cabinda this year. 2004 There were few reported violent incidences this year. Following early reports of human rights abuses by both sides of the conflict, a visit by a UN representative to the region noted significant progress. Later, a human rights group monitoring the situation in Cabinda accused government security forces of human rights abuses. 50,000 refugees repatriated during the year, short of the UNHCR’s goal of 90,000. 2003 Rebel bands remained active even as the government reached a “clean up” phase of the military campaign in the Cabinda enclave that began in 2002. Both sides were accused of human rights violations and at least 50 civilians died. Type of Conflict: State formation Parties to the Conflict: 1) Government, led by President Jose Eduardo dos Santos: Ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA); 2) Rebels: The two main rebel groups, the Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave (FLEC) and the Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave Cabinda Armed Forces (FLEC FAC), announced their merger on 8 September 2004. -

West Africa Geology and Total Petroleum Systems

Geology and Total Petroleum Systems of the West-Central Coastal Province (7203), West Africa 0° 5°E 10°E 15°E 20°E NIGER CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC DELTA CAMEROON 5°N DOUALA BANGUI GULF OF DOUALA, KRIBI- MALABO YAOUNDE GUINEA CAMPO BASINS RIO MUNI BASIN EQ. GUINEA CABO SAN JUAN ARCH ANNOBON-CAMEROON LIBREVILLE 0° VOLCANIC AXIS GABON N'KOMI FRACTURE DEMOCRATIC ZONE REPUBLIC OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO CONGO GABON BASIN CASAMARIA BRAZZAVILLE HIGH 5°S CONGO ANGOLA (CABINDA) KINSHASA ATLANTIC BASIN OCEAN AMBRIZ ARCH LUANDA 10°S ANGOLA KWANZA (CUANZA) BASIN BENGUELA HIGH BENGUELA BENGUELA BASIN 15°S NAMIBE BASIN 0 250 500 KILOMETERS NAMIBIA LVIS RIDGE WA U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2207-B U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geology and Total Petroleum Systems of the West-Central Coastal Province (7203), West Africa By Michael E. Brownfield and Ronald R. Charpentier U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2207-B U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior P. Lynn Scarlett, Acting Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 Posted online June 2006 Version 1.0 This publication is only available online at http://www.usgs.gov/bul/2207/B/ For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Angola Assessment

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit 1 CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 –1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 – 2.2 III HISTORY 3.1 – 3.23 Government Amnesties 3.28 – 3.31 Removals 3.32 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE Security situation 4.1 – 4.18 The Judiciary 4.19 – 4.25 Military Service 4.26 – 4.31 Social Welfare 4.32 – 4.36 Prisons Conditions 4.37 – 4.38 Torture 4.39 – 4.40 Disappearance 4.41 – 4.43 The Constitution 4.44 – 4.45 V HUMAN RIGHTS A: INTRODUCTION 5.1 Human Rights monitoring 5.2 – 5.10 B: SPECIFIC GROUPS Refugees & Internally Displaced Person 5.11 – 5.16 UNITA 5.17 – 5.36 UNITA-R 5.37 – 5.38 F.L.E.C/Cabindans 5.39 – 5.48 Ethnic Groups 5.50 – 5.51 Bakongo 5.52 – 5.60 Women 5.61 – 5.63 Children 5.64 – 5.67 Female Genital Mutilation 5.68 C: RESPECT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES Rights of the Individual 5.69 – 5.73 Freedom of religion 5.74 – 5.77 Freedom of speech and press 5.78 – 5.88 Freedom of Assembly & Association 5.89 – 5.93 Freedom of Movement 5.94 – 5.96 Internal flight 5.97 – 5.98 Emigration and Asylum 5.99 Landmines 5.100 – 5.103 ANNEX A: Political parties ANNEX B: Prominent people – past and present ANNEX C: Tribes and languages ANNEX D: Chronology ANNEX E: Election results ANNEX F: Glossary ANNEX G: Main newspapers ANNEX H: Bibliography ANNEX I: Bulletin 02/99 I. -

Africa in Focus, We Are Most Pleased to Release the Fifth Issue of Africa In

Welcome to Africa In Focus, We are most pleased to release the fifth issue of Africa In Focus. Our aim with these bi-monthly brief reports is to provide you with an update on relevant news and key legal issues pertaining to Africa which may be of interest to you and to your business, complemented, whenever pertinent, with overviews on regulatory developments in the Angola and Mozambique jurisdictions. Capital market activities in Africa have an unsurpassable role in the strengthening of the economic growth of the continent. It is expected that the development of such activities in various countries will contribute to boost investors’ confidence and offer diversified and attractive investment opportunities for global emerging market players. In this edition we speak about some of the achievements in 2013 and also the challenges that lie before us. We have also included several articles we wrote on African matters. If you feel there are developments of information you have read in these documentation, as well as comments or suggestions you would like to make, we would be very glad to hear from you so please let us know by emailing [email protected]. With very best wishes, VdAtlas Through its VdAtlas – International Plataform, VdA has developed over the years a strong network of leading firms in Portuguese speaking Africa that covers all such jurisdictions. For further information about our Africa practice, please click here. IN-DEPHT In-Depht “2013: Promising steps for a promising 2013: Promising steps for a promising future in capital markets future in capital markets” Talking About 2013 has been quite a rewarding year for capital markets in African Portuguese speaking countries. -

SWOT Data Contributors

SWOT Data Contributors Guidelines of Data Use and Citation The olive and Kemp’s ridley nesting data below correspond directly to this report’s feature maps (pages 32–34), and are organized alphabetically by country, then by data record number as listed on the map. every data record with a point on the map is numbered to correspond with that point. The data come from a wide variety of sources and in many cases have not been previously published. To use data for research or publication, you must obtain permission from the data provider and must cite the original source indicated in the “data source” field of each record. in the records that follow, nesting data are reported from the most recent available year or nesting season or are reported as an annual average number of clutches based on the reported years of study. raw count data are reported as number of clutches, but are displayed on the maps in generalized bins (e.g., 1–10 clutches, 11–100 clutches, and so on) to facilitate interpretation. For more information on data conversions, see the box on page 31. Beaches for which count data were not available are listed as “unquantified.” Additional metadata are available for many of these data records, including information on beach length, monitoring effort, and other comments, and may be found online at www.seaturtlestatus.org. Following nesting data records, we have also included citations for satellite telemetry, genetic stocks, and information used to create the global distributions. Special Acknowledgments s pecial thanks go to Brendan Hurley for extraction, synthesis, and formatting of published data displayed in the maps. -

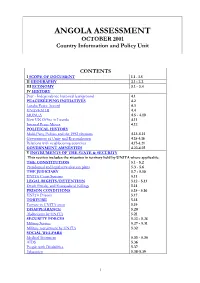

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 III ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.4 IV HISTORY Post - Independence historical background 4.1 PEACEKEEPING INITIATIVES 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.3 UNAVEM III 4.4 MONUA 4.5 - 4.10 New UN Office in Luanda 4.11 Internal Peace Moves 4.12 POLITICAL HISTORY Multi-Party Politics and the 1992 elections 4.13-4.14 Government of Unity and Reconciliation 4.15-4.16 Relations with neighbouring countries 4.17-4.21 GOVERNMENT AMNESTIES 4.22-4.25 V INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE & SECURITY This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. THE CONSTITUTION 5.1 - 5.2 Presidential and legislative election plans 5.3 - 5.6 THE JUDICIARY 5.7 - 5.10 UNITA Court Systems 5.11 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.12 - 5.13 Death Penalty and Extrajudicial Killings 5.14 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.15 - 5.16 UNITA Prisons 5.17 TORTURE 5.18 Torture in UNITA areas 5.19 DISAPPEARANCE 5.20 Abductions by UNITA 5.21 SECURITY FORCES 5.22 - 5.26 Military Service 5.27 - 5.31 Military recruitment by UNITA 5.32 SOCIAL WELFARE Medical Treatment 5.33 - 5.35 AIDS 5.36 People with Disabilities 5.37 Education 5.38-5.39 1 VI HUMAN RIGHTS- GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE SITUATION Introduction 6.1 SECURITY SITUATION Recent developments in the Civil War 6.2 - 6.17 Security situation in Luanda 6.18 - 6.19 Landmines 6.20 - 6.22 Human Rights monitoring 6.23 - 6.26 VII SPECIFIC GROUPS REFUGEES 7.1 Internally Displaced Persons & Humanitarian Situation 7.2-7.5 UNITA 7.6-7.8 Recent Political History of UNITA 7.9-7.12 UNITA-R 7.13-7.14 UNITA Military Wing 7.15-7.20 Surrendering UNITA Fighters 7.21 Sanctions against UNITA 7.22-7.25 F.L.E.C/CABINDANS 7.26 History of FLEC 7.27-7.28 Recent FLEC activity 7.29-7.34 The future of Cabindan separatists 7.35 ETHNIC GROUPS 7.36-7.37 Bakongo 7.38-7.46 WOMEN 7.47 Discrimination against women 7.48-7.59 CHILDREN 7.50-7.55 VIII RESPECT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. -

GENERAL PROCUREMENT NOTICE the Republic of Angola Cabinda Province Agriculture Value Chains Development Project (CPAVCDP) 1

GENERAL PROCUREMENT NOTICE The Republic of Angola Cabinda Province Agriculture Value Chains Development Project (CPAVCDP) 1. The republic of Angola has received a loan of 101.070.000 USD from the African Development Bank and funding from the government of Angola to finance the Cabinda Province Agriculture Value Chains Development Project (CPAVCDP) with a total budget of 123,150,580 USD. 2. The development objective of the project is to contribute to food and nutritional security, employment generation and shared wealth creation along the commodity value chain. The Specific project objectives are to increase farmers’ food and nutrition security and incomes through increased agricultural output and value addition. The Project will also contribute to enhance income of small and medium enterprises engaged in input supply, production, processing, storage and marketing of selected commodities on a sustainable basis. 3. The proposed CPAVCDP is composed of three components: (i) Commodity Value Chains Development; (ii) Infrastructure Development; and (iii) Project Management and Monitoring and Evaluation. The project focuses on the provision of the enabling environment for agricultural development and value addition of staple crops (cassava, banana, sweet potato, peanut, and beans); cash crops (coffee, cocoa and oil palm); marine and inland fisheries; poultry and small ruminants; and horticulture (vegetables and fruits). It will rehabilitate or construct rural and resilient infrastructure, namely feeder roads to link production clusters to markets, agro processing centers, market centers, community health centers, primary schools, potable water facilities in the communities and improve rural energy access 4. Procurement of goods and works and the acquisition of consulting services, financed by the Bank for the project, will be carried out in accordance with the “Procurement Policy for Bank Group Funded Operations”, dated October 2015 and following the provisions stated in the Financing Agreement. -

The Angolan Struggle, Produce and Resist 4

The Angolan Struggle, Produce And ResIst 4 ANGOLA On November 11, 1975, Angola was granted independence from Portugal after 500 years of colonial rule . This date represented a victory for the anti-colonial struggle in Angola, but it also marked the start of a bloody civil war, a war which recently culminated in victory for the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). The civil war was fought between three groups that had played various roles in the national liberation struggle . The most firmly established and progressive group is the MPLA . The MPLA was formed in 1957 and began the armed struggle against Portuguese colonialism in 1961 . Its president is Agostinho Neto. In 1963 another group, the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), was organized under the leadership of Holden Roberto. The third group is the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), led by Jonas Savimbi. By 1967 the MPLA had launched several successful guerrilla campaigns and forced the Portuguese to commit some 50,000 troops to an ill-fated effort to stop the national liberation struggle . In 1969 the Organization of African Unity termed the MPLA the only movement that truly represented the people of Angola, and in early 1976 the OAU formally recognized the MPLA-led government of the Peoples Republic of Angola. Angola, located on the southwest coast of Africa, covers an area of some 481,226 square miles and is the largest of the former Portuguese colonies. It has a population of about six million, and its capital is Luanda . -

Angola Chronology

Angola Chronology http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.af000008 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Angola Chronology Alternative title Angola Chronology Author/Creator Africa Fund Publisher Africa Fund Date 1976-02 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, South Africa, United States Coverage (temporal) 1956 - 1976 Source Africa Action Archive Rights By kind permission of Africa Action, incorporating the American Committee on Africa, The Africa Fund, and the Africa Policy Information Center. Description Angola Chronology. MPLA. Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola. FNLA. National Front for the Liberation of Angola.