Orson Welles, the War of the Worlds Copyright, and Why We Should Recognize Idea-Contributors As Joint Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me and Orson Welles Press Kit Draft

presents ME AND ORSON WELLES Directed by Richard Linklater Based on the novel by Robert Kaplow Starring: Claire Danes, Zac Efron and Christian McKay www.meandorsonwelles.com.au National release date: July 29, 2010 Running time: 114 minutes Rating: PG PUBLICITY: Philippa Harris NIX Co t: 02 9211 6650 m: 0409 901 809 e: [email protected] (See last page for state publicity and materials contacts) Synopsis Based in real theatrical history, ME AND ORSON WELLES is a romantic coming‐of‐age story about teenage student Richard Samuels (ZAC EFRON) who lucks into a role in “Julius Caesar” as it’s being re‐imagined by a brilliant, impetuous young director named Orson Welles (impressive newcomer CHRISTIAN MCKAY) at his newly founded Mercury Theatre in New York City, 1937. The rollercoaster week leading up to opening night has Richard make his Broadway debut, find romance with an ambitious older woman (CLAIRE DANES) and eXperience the dark side of genius after daring to cross the brilliant and charismatic‐but‐ sometimes‐cruel Welles, all‐the‐while miXing with everyone from starlets to stagehands in behind‐the‐scenes adventures bound to change his life. All’s fair in love and theatre. Directed by Richard Linklater, the Oscar Nominated director of BEFORE SUNRISE and THE SCHOOL OF ROCK. PRODUCTION I NFORMATION Zac Efron, Ben Chaplin, Claire Danes, Zoe Kazan, Eddie Marsan, Christian McKay, Kelly Reilly and James Tupper lead a talented ensemble cast of stage and screen actors in the coming‐of‐age romantic drama ME AND ORSON WELLES. Oscar®‐nominated director Richard Linklater (“School of Rock”, “Before Sunset”) is at the helm of the CinemaNX and Detour Filmproduction, filmed in the Isle of Man, at Pinewood Studios, on various London locations and in New York City. -

I N S I D E T H I S I S S

Publications and Products of August/août 2003 Volume/volume 97 Number/numéro 4 [701] The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Observer’s Calendar — 2004 This calendar was created by members of the RASC. All photographs were taken by amateur astronomers using ordinary camera lenses and small telescopes and represent a wide spectrum of objects. An informative caption accompanies every photograph. It is designed with the observer in mind and contains comprehensive The Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Le Journal de la Société royale d’astronomie du Canada astronomical data such as daily Moon rise and set times, significant lunar and planetary conjunctions, eclipses, and meteor showers. The 1998, 1999, and 2000 editions each won the Best Calendar Award from the Ontario Printing and Imaging Association (designed and produced by Rajiv Gupta). Individual Order Prices: $16.95 CDN (members); $19.95 CDN (non-members) $14.95 USD (members); $17.95 USD (non-members) (includes postage and handling; add GST for Canadian orders) The Beginner’s Observing Guide This guide is for anyone with little or no experience in observing the night sky. Large, easy to read star maps are provided to acquaint the reader with the constellations and bright stars. Basic information on observing the Moon, planets and eclipses through the year 2005 is provided. There is also a special section to help Scouts, Cubs, Guides, and Brownies achieve their respective astronomy badges. Written by Leo Enright (160 pages of information in a soft-cover book with otabinding that allows the book to lie flat). Price: $15 (includes taxes, postage and handling) Skyways: Astronomy Handbook for Teachers Teaching Astronomy? Skyways Makes it Easy! Written by a Canadian for Canadian teachers and astronomy educators, Skyways is: Canadian curriculum-specific; pre-tested by Canadian teachers; hands-on; interactive; geared for upper elementary; middle school; and junior high grades; fun and easy to use; cost-effective. -

9Th Grade Ela

9TH GRADE ELA Week of: MAY 11TH WICHITA PUBLIC SCHOOLS 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th Grades Your child should spend up to 90 minutes over the course of each day on this packet. Consider other family-friendly activities during the day such as: Learn how to do laundry. Create a cartoon image Make a bucket list of Look up riddles to Wash the laundry, of your family. things to do after the solve with someone fold and put the quarantine is over with in your family. laundry away. your family. Mindful Minute: Write Do a random act of Teach someone in your Put together a puzzle down what a typical day kindness for someone in family to play one of your with your family. was like pre-quarantine your house. video games. and during quarantine. How have things changed? *All activities are optional. Parents/Guardians please practice responsibility, safety, and supervision. For students with an Individualized Education Program (IEP) who need additional support, Parents/Guardians can refer to the Specialized Instruction and Supports webpage, contact their child’s IEP manager, and/or speak to the special education provider when you are contacted by them. Contact the IEP manager by emailing them directly or by contacting the school. The Specialized Instruction and Supports webpage can be accessed by clicking HERE or by navigating in a web browser to https://www.usd259.org/Page/17540 WICHITA PUBLIC SCHOOLS CONTINUOUS LEARNING HOTLINE AVAILABLE 316-973-4443 MARCH 30 – MAY 21, 2020 MONDAY – FRIDAY 11:00 AM – 1:00 PM ONLY For Multilingual Education Services (MES) support, please call (316) 866-8000 (Spanish and Proprio) or (316) 866-8003 (Vietnamese). -

The Only Defense Is Excess: Translating and Surpassing Hollywood’S Conventions to Establish a Relevant Mexican Cinema”*

ANAGRAMAS - UNIVERSIDAD DE MEDELLIN “The Only Defense is Excess: Translating and Surpassing Hollywood’s Conventions to Establish a Relevant Mexican Cinema”* Paula Barreiro Posada** Recibido: 27 de enero de 2011 Aprobado: 4 de marzo de 2011 Abstract Mexico is one of the countries which has adapted American cinematographic genres with success and productivity. This country has seen in Hollywood an effective structure for approaching the audience. With the purpose of approaching national and international audiences, Meximo has not only adopted some of Hollywood cinematographic genres, but it has also combined them with Mexican genres such as “Cabaretera” in order to reflect its social context and national identity. The Melodrama and the Film Noir were two of the Hollywood genres which exercised a stronger influence on the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema. Influence of these genres is specifically evident in style and narrative of the film Aventurera (1949). This film shows the links between Hollywood and Mexican cinema, displaying how some Hollywood conventions were translated and reformed in order to create its own Mexican Cinema. Most countries intending to create their own cinema have to face Hollywood influence. This industry has always been seen as a leading industry in technology, innovation, and economic capacity, and as the Nemesis of local cinema. This case study on Aventurera shows that Mexican cinema reached progress until exceeding conventions of cinematographic genres taken from Hollywood, creating stories which went beyond the local interest. Key words: cinematographic genres, melodrama, film noir, Mexican cinema, cabaretera. * La presente investigación fue desarrollada como tesis de grado para la maestría en Media Arts que completé en el 2010 en la Universidad de Arizona, Estados Unidos. -

Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm

JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 3 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm Edited by Cristina M. Giannantonio Amy E. Hurley-Hanson Associate Professors of Management, George L. Argyros School of Business and Economics, Chapman University, USA NEW HORIZONS IN LEADERSHIP STUDIES Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 4 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 © Cristina M. Giannantonio andAmy E. Hurley-Hanson 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited The Lypiatts 15 Lansdown Road Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. William Pratt House 9 Dewey Court Northampton Massachusetts 01060 USA A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946802 This book is available electronically in the ElgarOnline.com Business Subject Collection, E-ISBN 978 1 78100 212 4 ISBN 978 1 78100 211 7 (cased) Typeset by Columns Design XML Ltd, Reading Printed and bound in Great Britain by T.J. International Ltd, Padstow Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 2 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 1 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:57:46 2013 14. Extreme leadership as creative leadership: reflections on Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather Charalampos Mainemelis and Olga Epitropaki INTRODUCTION How do extreme leadership situations arise? According to one view, they are triggered by environmental factors that have nothing or little to do with the leader. -

Orson Welles's Deconstruction of Traditional Historiographies In

“How this World is Given to Lying!”: Orson Welles’s Deconstruction of Traditional Historiographies in Chimes at Midnight Jeffrey Yeager, West Virginia University ew Shakespearean films were so underappreciated at their release as Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight.1 Compared F to Laurence Olivier’s morale boosting 1944 version of Henry V, Orson Welles’s adaptation has never reached a wide audience, partly because of its long history of being in copyright limbo.2 Since the film’s debut, a critical tendency has been to read it as a lament for “Merrie England.” In an interview, Welles claimed: “It is more than Falstaff who is dying. It’s the old England, dying and betrayed” (qtd. in Hoffman 88). Keith Baxter, the actor who plays Prince Hal, expressed the sentiment that Hal was the principal character: Welles “always saw it as a triangle basically, a love story of a Prince lost between two father figures. Who is the boy going to choose?” (qtd. in Lyons 268). Samuel Crowl later modified these differing assessments by adding his own interpretation of Falstaff as the central character: “it is Falstaff’s winter which dominates the texture of the film, not Hal’s summer of self-realization” (“The Long Good-bye” 373). Michael Anderegg concurs with the assessment of Falstaff as the central figure when he historicizes the film by noting the film’s “conflict between rhetoric and history” on the one hand and “the immediacy of a prelinguistic, prelapsarian, timeless physical world, on the other” (126). By placing the focus on Falstaff and cutting a great deal of text, Welles, Anderegg argues, deconstructs Shakespeare’s world by moving “away from history and toward satire” (127). -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

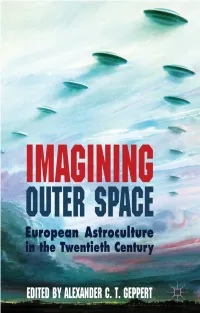

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C. T. Geppert FLEETING CITIES Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe Co-Edited EUROPEAN EGO-HISTORIES Historiography and the Self, 1970–2000 ORTE DES OKKULTEN ESPOSIZIONI IN EUROPA TRA OTTO E NOVECENTO Spazi, organizzazione, rappresentazioni ORTSGESPRÄCHE Raum und Kommunikation im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert NEW DANGEROUS LIAISONS Discourses on Europe and Love in the Twentieth Century WUNDER Poetik und Politik des Staunens im 20. Jahrhundert Imagining Outer Space European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century Edited by Alexander C. T. Geppert Emmy Noether Research Group Director Freie Universität Berlin Editorial matter, selection and introduction © Alexander C. T. Geppert 2012 Chapter 6 (by Michael J. Neufeld) © the Smithsonian Institution 2012 All remaining chapters © their respective authors 2012 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. -

The Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide the Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide

(Read free ebook) The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide QxKpnBVVk The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide GF-51433 USmix/Data/US-2015 4.5/5 From 294 Reviews Kevin C. Fitzpatrick DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub 13 of 13 people found the following review helpful. A great way to introduce yourself to a group who made literary historyBy Greg HatfieldIt seems my entire life has been connected to the Algonquin Round Table. When I first discovered Harpo Marx, as a youngster, it led me to his autobiography, Harpo Speaks,where I then learned about the Round Table. Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, Heywood Broun, and all the rest who made up the Vicious Circle, became an obsession to me and I had to learn about their lives and, more importantly, their work.Kevin Fitzpatrick has done a remarkable job with this book, putting the group into a historical perspective, and giving the reader a terrific overview of what made the Algonquin Round Table unique and worthy of your time. They were the leading writers and critics of the 1920's, who really did enjoy one another's company, meeting practically every day for lunch for ten years at the Algonquin Hotel.Fitzpatrick says, in one section, that there isn't a day, in this modern era, where someone, somewhere, mentions one of the group in a glowing context (I'm paraphrasing here). The fact remains that the work of Kaufman, Mrs. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Innovators: Filmmakers

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: FILMMAKERS David W. Galenson Working Paper 15930 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15930 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Filmmakers David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15930 April 2010 JEL No. Z11 ABSTRACT John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were experimental filmmakers: both believed images were more important to movies than words, and considered movies a form of entertainment. Their styles developed gradually over long careers, and both made the films that are generally considered their greatest during their late 50s and 60s. In contrast, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard were conceptual filmmakers: both believed words were more important to their films than images, and both wanted to use film to educate their audiences. Their greatest innovations came in their first films, as Welles made the revolutionary Citizen Kane when he was 26, and Godard made the equally revolutionary Breathless when he was 30. Film thus provides yet another example of an art in which the most important practitioners have had radically different goals and methods, and have followed sharply contrasting life cycles of creativity. -

Tommy Dorsey 1 9

Glenn Miller Archives TOMMY DORSEY 1 9 3 7 Prepared by: DENNIS M. SPRAGG CHRONOLOGY Part 1 - Chapter 3 Updated February 10, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS January 1937 ................................................................................................................. 3 February 1937 .............................................................................................................. 22 March 1937 .................................................................................................................. 34 April 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 53 May 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 68 June 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 85 July 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 95 August 1937 ............................................................................................................... 111 September 1937 ......................................................................................................... 122 October 1937 ............................................................................................................. 138 November 1937 .........................................................................................................