Disproportionate Importance of Nearshore Habitat for the Food Web of a Deep Oligotrophic Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pygmy Whitefish Fact Sheet

Sensitive Species ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Pygmy Whitefish (Prosopium coulteri) State Status: Sensitive, 1998 Federal Status: Species of concern Recovery Plans: None State Management Plan: None The pygmy whitefish, a small (usually < 20 cm) Figure 1. Pygmy whitefish (photo from Wydoski and member of the family Salmonidae, is distributed Whitney 2003). across the northern tier of the United States, throughout western Canada and north into southeast Alaska, and in one lake in Russia (Hallock and Mongillo 1998). Their widely scattered distribution, primarily in deep lakes, suggests they are relics of a wider distribution prior to the last ice age (Wydoski and Whitney 2003). Washington is at the extreme southern edge of their native range in North America. Pygmy whitefish are most commonly found in cool oligotrophic lakes and streams of mountainous regions. However, they have been collected from smaller, shallow, more productive lakes in British Columbia and Washington. Pygmy whitefish eat crustaceans, aquatic insect larvae and pupae, fish eggs, and small mollusks. Pygmy whitefish are important forage fish for larger predatory species including bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus). Historically, pygmy whitefish resided in at least 16 lakes in Washington (Figure 2; Hallock and Mongillo 1998). Currently they inhabit only nine. Their demise in six lakes is attributed to piscicides, introduction of exotic fish species and/or declining water *# quality. Because of the very limited range of the *# pygmy whitefish in Washington, they are *# vulnerable to additional extirpations without *# *#*# *# *# *# *# cooperative management. *# Pygmy whitefish surveys require specialized *# *# *#*#*# techniques because of the fish's small size and tendency to inhabit the deeper portions of lakes; their presence in lakes heavily sampled for other species sometimes goes undetected. -

History & Culture

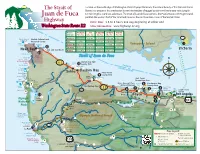

Tatoosh Island & Lighthouse Washington Cape Flattery 10 Neah Bay Vancouver Island State Route 112 8 Victoria Neah Bay Au to and Hobuck Beach 9 Makah Makah Strait of Juan de Fuca Bay Reservation P The Strait of Sooes Ri assenger-Only Sekiu 112 Point Clallam Shi Shi Beach ve Bay 5 r 6 Point of er Clallam Bay the Arches Sekiu F DE o Riv erries UAN k J FUCA Ho Ozette Indian Hoko-Ozette Pillar Point Cape Pysht Alava Reservation Road HIGHWAY r Pysht River Crescent Ozette ve Bay Island 7 Big Ri The Working Forest 2 Freshwater West Twin Striped 113 4 3 Bay Ediz Hook Sand Point Dickey River Peak Port Lake Lake Beaver Lake East Twin Lyre River Angeles ITINERARY #1 Ozette River Joyce 112 Olympic Salt Creek Lake Sappho er Pleasant Fairholm 1 National er 101 rk 101 Lake Crescent Riv Park Fo Riv Lake HISTORY & CULTURE ckey Beaver To Seattle Sol Duc Riv er Sutherland Di East ckey Di ah River Heart O’ the orth Fork Calaw S N Summer Hills Ranger y y Onl Station Summer Only Mora Olympic National Forest S Hurricane Ranger Sol Duc Hot Springs Ridge 1. ElwhaStation River Interpretive Center This self-guided Scenterol Duc Falls presents an overview of the largest Highway 112 has Rialto Beach Forks Elwha Ri U.S. Forest Service and Quileute Indian 110 National Park Service River ve damRese removalrvation and restoration project in the Unitedk Calaw ahStates occurring on the nearby Elwha River.r Nature trails lead Information Station South For Olympic National Park La Push Bogachiel Map Legend from the parking lot to views ofState the Park Elwha River gorge and the former Elwha Dam site. -

Bicycling the O Lympic Peninsula

Eastern Clallam County Bicycle Map Be Visible • Be Alert • Wear a Helmet • Have Fun RCW 46.61.755 states: Signal before turns and lane Be visible day or night. Be courteous. Choose the best way to turn left: Ride defensively. Be aware of other Ride predictably. changes. Wear bright clothes. Traffic laws apply to persons ❚ LIKE a CAR—scan behind, yield, signal vehicles. Leave adequate space between you and riding bicycles. Audibly alert pedestrians as Check behind and ahead before RCW 46.61.780 states: you approach. and when safe, move into the left lane Do not pass on the right. parked cars. and turn left. Obey all traffic signs, signals and turning. At night you must have a Be careful of opening car doors. laws. Ride in the same direction white headlight and taillight Yield to pedestrians in the ❚ LIKE a PEDESTRIAN—dismount and CAUTION: Always watch for cars as traffic. Yield to vehicles with the or red rear reflector. crosswalk. walk your bike across the intersection stopping or turning. Do not weave in and out of parked cars right-of-way. in the crosswalk. and traffic. Twin Salt Creek County Park Crescent Bay Strait of Juan de Fuca Agate Bay d R r e Lyre River Pvt. Beach To iv gate R n d Clallam Bay i R w r T e d Pvt. t iv s R and Sekiu R Field Creek Lower Elwha Klallam e re r y e Crescent School W L . v i Striped Indian Reservation W R (Parking in South Whiskey Creek e r Peak End of Bus Route y end of lot beside gate L Salt Creek . -

A G~Ographic Dictionary of Washington

' ' ., • I ,•,, ... I II•''• -. .. ' . '' . ... .; - . .II. • ~ ~ ,..,..\f •• ... • - WASHINGTON GEOLOGICAL SURVEY HENRY LANDES, State Geologist BULLETIN No. 17 A G~ographic Dictionary of Washington By HENRY LANDES OLYMPIA FRAN K M, LAMBORN ~PUBLIC PRINTER 1917 BOARD OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY. Governor ERNEST LISTER, Chairman. Lieutenant Governor Louis F. HART. State Treasurer W.W. SHERMAN, Secretary. President HENRY SuzzALLO. President ERNEST 0. HOLLAND. HENRY LANDES, State Geologist. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. Go,:ernor Ernest Lister, Chairman, and Members of the Board of Geological Survey: GENTLEMEN : I have the honor to submit herewith a report entitled "A Geographic Dictionary of Washington," with the recommendation that it be printed as Bulletin No. 17 of the Sun-ey reports. Very respectfully, HENRY LAKDES, State Geologist. University Station, Seattle, December 1, 1917. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page CHAPTER I. GENERAL INFORMATION............................. 7 I Location and Area................................... .. ... .. 7 Topography ... .... : . 8 Olympic Mountains . 8 Willapa Hills . • . 9 Puget Sound Basin. 10 Cascade Mountains . 11 Okanogan Highlands ................................ : ....' . 13 Columbia Plateau . 13 Blue Mountains ..................................... , . 15 Selkirk Mountains ......... : . : ... : .. : . 15 Clhnate . 16 Temperature ......... .' . .. 16 Rainfall . 19 United States Weather Bureau Stations....................... 38 Drainage . 38 Stream Gaging Stations. 42 Gradient of Columbia River. 44 Summary of Discharge -

Draft CCP, Chapters 3-6, November 2012 (Pdf 3.0

Physical Environment Chapter 3 © Mary Marsh Chapter 6 Chapter 5 Chapter 4 Chapter 3 Chapter 2 Chapter 1 Environmental Human Biological Physical Alternatives, Goals, Introduction and Appendices Consequences Environment Environment Environment Objectives, and Strategies Background Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge Draft CCP/EA Chapter 3. Physical Environment 3.1 Climate and Climate Change 3.1.1 General Climate Conditions The climate at Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) is a mild, mid-latitude, west coast marine type. Because of the moderating influence of the Pacific Ocean, extremely high or low temperatures are rare. Summers are generally cool and dry while winters are mild but moist and cloudy with most of the precipitation falling between November and January (USDA 1987, WRCC 2011a). Annual precipitation in the region is low due to the rain shadow cast by the Olympic Mountains and the extension of the Coastal Range on Vancouver Island (Figure 3-1). Snowfall is rare or light. During the latter half of the summer and in the early fall, fog banks from over the ocean and the Strait of Juan de Fuca cause considerable fog and morning cloudiness (WRCC 2011a). Climate Change Trends The greenhouse effect is a natural phenomenon that assists in regulating and warming the temperature of our planet. Just as a glass ceiling traps heat inside a greenhouse, certain gases in the atmosphere, called greenhouse gases (GHG), absorb and emit infrared radiation from sunlight. The primary greenhouse gases occurring in the atmosphere include carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor, methane, and nitrous oxide. CO2 is produced in the largest quantities, accounting for more than half of the current impact on the Earth’s climate. -

The Resource

Chapter II THE RESOURCE LOCATOR MAP OF CLALLAM COUNTY DESCRIPTION OF PLANNING AREA • NARRATIVE • PHYSICAL FEATURES • CHARACTERISTIC LANDSCAPES HISTORIC RESOURCES • NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES • WASHINGTON STATE REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES APPENDICES • APPENDIX A – GENERALIZED FUTURE LAND USE MAP • APPENDIX B – PHYSIOGRAPHIC ZONES MAP • APPENDIX C – CHARACTERISTIC LANDSCAPES MAP LOCATOR OF MAP CLALLAM COUNTY Chapter II, Page 1 DESCRIPTION OF THE PLANNING AREA NARRATIVE Clallam County lies across the northern half of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, the northwest corner of the Pacific Northwest. Its western and northern boundaries are the Pacific Ocean and Strait of Juan de Fuca shorelines. The southern boundary cuts through Olympic National Park, the nearly million-acre wilderness interior of the Peninsula. The high mountains, rugged coastlines, deep forest, miles of unspoiled rivers, clean air and water, and mild marine climate offer a most unusual combination of environmental amenities. When the cultural, educational, and social amenities available in the cities and towns are considered, along with the range of living styles from small town to rural to backwoods, the county becomes a uniquely desirable place to live and work. The county is rich in natural resources. The Olympic Peninsula is one of the most productive timber-growing areas in the country, and 60 percent of Clallam County’s land area is in commercial timberland. The ocean waters once contained a vast fishery. Salmon have been the most significant species for commercial and sports fishermen, but twenty-four other commercially significant species are also landed. Some species of salmon have now become listed as threatened or endangered. -

Olympic Olympic National Park

Olympic Olympic National Park Lake Crescent Area Log Cabin Resort (closed winters) East Beach Rd. East Beach Mt. Muller Spruce 101 Railroad Trail Lake Sutherland Pyramid Peak Trail 101 Camp David Jr. Rd. Sol Duc Rd. Fairholme (store closed winters) LAKE CRESCENT Mt. Storm King A urora Ridge Sol Duc Riv Tr Aurora Creek Barnes Creek er ail Storm King Trail Ranger Station SEE AREA DETAIL ON BACK 0 North 4.83 kms 0 3 miles Pa rk Sapphire Setting Boundar Lake Crescent Area Information ake Crescent, a cold, clear,y Facilities: Storm King Ranger Station: If staffing allows, open in sum- glacially-carved lake, owes its mer with information and book sales. Lake Crescent Lodge L existence to ice. Its azure and Log Cabin Resort: lodging, restaurants, boat rentals depths, which plummet to 624 (both open summer only). Fairholme Store: groceries and feet, were gouged by huge ice sheets boat rentals (summer only). thousands of years ago. As the ice Camping: Fairholme: 87 sites (one accessible), fire pits with retreated, it left behind a steep valley grates, picnic tables, potable water, animal-proof that filled with the clear blue waters food storage lockers, accessible restrooms, RV of Lake Crescent. dump station. Open early April to late October. The lake's waters have very little Log Cabin Resort runs a summer-only RV nitrogen. This limits the growth campground. of phytoplankton, tiny plants (like Picnic Areas: East Beach: beach, accessible vault toilet, algae) that float in lake waters. fire pits, tables. Bovee's Meadow: beach, Without them, the water stays clear. -

Bugler 2010 Designer and Editor Glines Canyon Dam (Left)

8 Summer 2010 Olympic National Park BUGLER Summer Newspaper 2010 OlComeOlOlympic’ympic’ympic’ Explores WWs ilderilderildernessnessness Wilderness is... a place for people seeking solitude, escape, wildness, beauty and much more. A place for clean water, clean air, abundant wildlife, and diverse and unique plants. A place for the solo adventurer, families, mountaineers and for friends. A place for the young and the old. Wilderness Take A is a place for all people. For the past 25 years I have camped and hiked all over the west and Olympic National Park is still one of my favorite places. In this spectacular park my family and I can enjoy the comfort of a campground, take a short day hike or Last Look embark on a backpacking trip. I am always amazed that at Olympic I can stand on a sandy beach with waves By BARB MAYNES, Public Information Officer lapping at my feet and gaze out past mammoth sea stacks at the Pacific fter years of planning and preparation, Olympic Ocean, and the next day I can become immersed in the refreshing embrace National Park is gearing up for the largest dam of the temperate rain forest. Or I can walk through groves of giant trees removal in U.S. history and celebrating the ‘last while following the path of a crystal clear river up to its source in the lofty, A snow covered mountain passes and peaks that overlook the valley below. dam summer’ in the Elwha River Valley. Next summer, removal of Elwha and Glines Canyon dams on the My spine has tingled as a giant bull elk and I have watched a mountain lion Elwha River will begin, the culminating step in a run along a huge log in the rain forest. -

Singers Lake Crescent Tavern Histonc District

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name Singer's Lake Crescent Tavern other name/site number Lake Crescent Lodge: Lake Crescent Tavern. Lake Crescent Lodge Historic District________ 2. Location street & number Barnes Point. S. Shore of Lake Crescent. Highway 101: D not for publication Lake Crescent Sub-district city or town Olympic National Park Headquarters: Port Angeles D vicinity state Washington code WA county Clallam code 009 zip code 98362 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this 2Snc^.-.nomination __request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties irt the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property xC meets ___does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Preface Preface

PREFACE PREFACE This Historic Structures Report was completed in accordance with examples of recreational development during the Forest Service the University of Oregon, Historic Preservation Masters program administration. The primary house refl ects the craftsman archi- and Terminal Project requirements. This report was also written tectural period and is the only remaining historic recreational resi- with the intention of assisting Olympic National Park in its stew- dence of this period and style owned by Olympic National Park. ardship of the presented historic buildings. The Wendel property was listed on the National Register of His- toric Places in 2005. An Historic Structures Report is a planning guide. The purpose of a Historic Structure Report to develop an assimilation of historic context and existing conditions of a building(s) to form the basis of recommendations on the care and conservation of the historic resource. The subject of the report is two structures located within Olympic National Park on the North shore of Lake Crescent, near the head of the Lyre River. The Wendel House and associated boathouse were built in 1936. The two structures are signifi cant Wendel House - Historic Structure Report Olympic National Park Page TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES INTRODUCTION STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ADMINISTRATIVE DATA GEOGRAPHIC/NATURAL SETTING CHAPTER I: Historic Background Recreational Development The Olympics Before the Forest Reserve Olympic Forest Reserve 1893-1905 Recreational Development in the Olympics Before the National -

Highway Drive Time: 1.5 to 2 Hours One Way Beginning at Either End Washington State Route 112 More Information

Located on the north edge of Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula, the natural beauty of this National Scenic The Strait of Byway is as unique as it is spectacular. Its remote stretches of rugged coastline will make your ride along its Juan de Fuca 61-mile length a stand-out adventure. The Strait of Juan de Fuca connects the Pacic Ocean with Puget Sound, parallels the western half of the Strait and traverses the northwestern corner of the United States. Highway Drive Time: 1.5 to 2 hours one way beginning at either end Washington State Route 112 More information: www.highway112.org Distances Port Angeles Joyce Cl. Bay/Sekiu Lake Ozette Neah Bay & Mileages Miles / Time Miles / Time Miles / Time Miles / Time Miles / Time 17 Tatoosh Island & Makah Cultural and Port Angeles 16/24 min. 50/1 hr.16 min. 75/2hrs.7 min. 68/1 hr.47 min. Lighthouse Research Center Joyce 16/24 min. 34/53 min. 59/1 hr.45 min. 54/1 hr.20 min. Cape Flattery Neah Bay Cl. Bay/Sekiu 50/1 hr.16 min. 34/53 min. 25/50 min. 20/32 min. Vancouver Island 12 Lake Ozette 75/2hrs.7 min. 59/1 hr.45 min. 25/50 min. 38/1 hr.11 min. Neah Bay Sail and Seal Rocks Victoria Neah Bay 68/1 hr.47 min. 54/1 hr.20 min. 75/2hrs.7 min. 38/1 hr.11 min. Au to and P Hobuck Beach 13 Makah Strait of Juan de Fuca Makah Bay Reservation assenger-Only F Flattery Rocks Sooes Ri National Wildlife Clallam Bay Spit Refuge Sekiu 112 Point ve 10 County Park Shi Shi Beach r Clallam Bay Point of the Arches erries er Clallam Bay Ozette Indian Sekiu Pillar Point o Riv Village Hok 9 County Park Archaeological Pysht -

2.1 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Olympic Peninsula Landscapes, And

Chapter 2.1 Natural Environment Page 2.1-1 2.1 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Olympic Peninsula landscapes, and the region’s flora and fauna, have been shaped by the geology and climatic history of the region. The landscapes have been reworked by the persistent, long-term action of gradual environmental changes such as glaciation and mountain-building. They have responded to erratic, catastrophic events, such as major floods, fires, and the breaching of glacial lakes. And they evidence the pervasive effects of human influences. The wildlife and plantlife of the peninsula reflect this long, complex, and significantly altered character. This section discusses the many factors that define the current condition of the natural environment of WRIA 18. This is a diverse area with important differences across its full extent. Consequently, the discussion below contains some information that is generally applicable to the entire planning area. In addition, much work has been done in specific areas within WRIA 18 that makes it possible to present more detailed information relating to portions of the WRIA, especially in distinguishing between East WRIA 18 and West WRIA 18. Where possible and appropriate, information here is presented separately for these eastern and western portions. 2.1.1 Geography West WRIA 18 – Elwha Morse Planning Area West WRIA 18 (WRIA 18W) includes, on the west, the Elwha River and its tributaries, Morse Creek on the east, and the smaller, urban drainages between, including Dry, Tumwater, Valley, Peabody, White, Ennis, and Lees creeks. The headwaters of the Elwha River and Morse Creek lie in the Olympic Mountains. The smaller streams originate in foothills to the north of the main Olympic range and along the northern boundary of Olympic National Park.