A Thicker Kind of Water Chad R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M-Phazes | Primary Wave Music

M- PHAZES facebook.com/mphazes instagram.com/mphazes soundcloud.com/mphazes open.spotify.com/playlist/6IKV6azwCL8GfqVZFsdDfn M-Phazes is an Aussie-born producer based in LA. He has produced records for Logic, Demi Lovato, Madonna, Eminem, Kehlani, Zara Larsson, Remi Wolf, Kiiara, Noah Cyrus, and Cautious Clay. He produced and wrote Eminem’s “Bad Guy” off 2015’s Grammy Winner for Best Rap Album of the Year “ The Marshall Mathers LP 2.” He produced and wrote “Sober” by Demi Lovato, “playinwitme” by KYLE ft. Kehlani, “Adore” by Amy Shark, “I Got So High That I Found Jesus” by Noah Cyrus, and “Painkiller” by Ruel ft Denzel Curry. M-Phazes is into developing artists and collaborates heavy with other producers. He developed and produced Kimbra, KYLE, Amy Shark, and Ruel before they broke. He put his energy into Ruel beginning at age 13 and guided him to RCA. M-Phazes produced Amy Shark’s successful songs including “Love Songs Aint for Us” cowritten by Ed Sheeran. He worked extensively with KYLE before he broke and remains one of his main producers. In 2017, Phazes was nominated for Producer of the Year at the APRA Awards alongside Flume. In 2018 he won 5 ARIA awards including Producer of the Year. His recent releases are with Remi Wolf, VanJess, and Kiiara. Cautious Clay, Keith Urban, Travis Barker, Nas, Pusha T, Anne-Marie, Kehlani, Alison Wonderland, Lupe Fiasco, Alessia Cara, Joey Bada$$, Wiz Khalifa, Teyana Taylor, Pink Sweat$, and Wale have all featured on tracks M-Phazes produced. ARTIST: TITLE: ALBUM: LABEL: CREDIT: YEAR: Come Over VanJess Homegrown (Deluxe) Keep Cool/RCA P,W 2021 Remi Wolf Sexy Villain Single Island P,W 2021 Yung Bae ft. -

ED 353 517 CG 024 735 TITLE Fighting Back: the Cultural

ED 353 517 CG 024 735 TITLE Fighting Back: The Cultural Context of Drug and Alcohol Use among Youth. INSTITUTION Social Development Commission, Milwaukee, WI. PUB DATE [92] NOTE 130p.; Funding for this study was provided by Fighting Back, United Way of Greater Milwaukee, and the Milwaukee Foundation. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; Asian Americans; *At Risk Persons; Blacks; Community Involvement; *Cultural Context; *Drinking; *Drug Use; Family Relationship; Hispanic Americans; *Incidence; Minority Groups; Substance Abuse; Whites; *Youth Problems IDENTIFIERS African Americans; Native Americans; Wisconsin (Milwaukee) ABSTRACT In this study 194 African American, Southeast Asian, Hispanic, Native American, and White adolescents and young adults aged 12 to 25 were interviewed during April and May of 1991. Subjects were recruited through several community-based organizations, schools, and other youth-serving programs in the Fighting Back program area ;.n Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Open-ended interviews were conducted and the interviews were taped, translated, and transcribed for analysis. Twenty-six percent reported that they had never used alcohol or drugs. Using alcohol and drugs in the company of friends was the primary recreational activity for 40% of those interviewed. Warnings against drug and alcohol abuse from family members did not seem to work. About half felt that their neighborhood was a good one to live in, with Whites expressing the most negative feelings about their neighborhoods. Youth perceptions of the effectiveness of community messages aimed at deterring youth from substance abuse were divided into three categories: effective, not effective, and Lomewhat effective. Youth who were involved in some form of organized community, sports, or church activity were less likely to be engaged in use and abuse of alcohol and drugs. -

C:\Users\Randy\Documents\Wesley\Poetry and Hymns\Charles Wesley Files\Published Primary Sources\First Editions Revised\Scriptur

Modernized text Scripture Hymns (1762), Vol. 21 [Baker list, #249] Editorial Introduction: Charles Wesley was sidelined in Bristol for much of 1760–61 with an extended illness (the gout). He frequently visited Bath nearby to drink the waters and he occupied his time writing a series of verse arising from reading through the entire Bible. Unlike his earlier work on the psalms and other scripture passages, which sought mainly to paraphrase scripture in verse, most of the work collected in this two-volume set is reflective in tone. The short hymns often pick up a single theme provoked by the passage being read, with emphasis on relevance to the current struggles in the Methodist movement. As Charles notes in the preface (included in volume 1), many of the hymns focus on current debates about Christian perfection. Charles also notes in the preface that the reflections on scripture contained in these short hymns were often suggested by reading alongside of scripture some commentaries on the text (particularly by Johann Bengel, Robert Gell and Matthew Henry). As he had done with his two-volume collection HSP (1749), Charles sought copyright protection for this two-volume set, registering it at Stationers Hall on August 23, 1762. While Charles does not provide a table of contents for his volume, we have provided one below, organized by scripture reference, because he occasionally gives a hymn on a particular verse out of sequence. Edition: Charles Wesley. Short Hymns on Select Passages of the Holy Scriptures. 2 vols. Bristol: Farley, 1762. Notes: John Wesley’s personal copy of this two-volume set is present in the remnants of his personal library at Wesley’s House, London (shelfmark, J. -

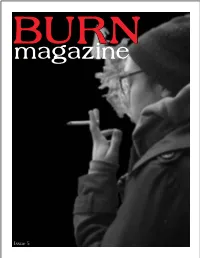

5 Letter from the Editors

BURNmagazine Issue 5 Letter from the Editors What is Burn? As new editors resurrecting Burn Magazine from its last publication in 2010, we look to embody our preceding editors’ hopes for Burn, despite moving into the future; that is, compiling a literary magazine that allows its readers to momentarily escape their busy collegiate lives in Boston and immerse themselves in the words, thoughts, and images of their undergraduate colleagues. We chose the following pieces based on both on their unique concepts and varying styles, though we decided against a specific theme for this issue to bind the contributions together aside from the fact that they all were written by undergraduates. Our hope is that because of the wide range of pieces we chose, Burn will appeal to all types of people at Boston University as a way to experience the creativity of those who may be outside of their discipline’s realm—we want this magazine and its contributors’ voices to reach people outside of just family and friends (though we do appreciate these you). We hope you enjoy the pieces we selected from our submissions this semester, and we look forward to the future of Burn Magazine. Best, Jenna Bessemer and Tori Sommerman, Co-Editors Zachary Bos, Advising Editor Founded in 2006 by Catherine Craft, Mary Sullivan, and Chase Quinn. Boston University undergraduates may send submissions to [email protected]. Manuscripts are considered year-round. Burn Magazine is published according to an irregular schedule by the Boston University Literary Society; printed by the Pen & Anvil Press. Front cover photograph by Tori Sommerman, COM 2013. -

El Paso Odyessy Tafari Amin Nugent University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2015-01-01 El Paso Odyessy Tafari Amin Nugent University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Nugent, Tafari Amin, "El Paso Odyessy" (2015). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1113. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1113 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. El Paso Odyssey TAFARI NUGENT Department of Creative Writing APPROVED: Lex Williford Chair Jeffery Sirkin Ph.D. Esther Al-Tabaa MA Charles Amber, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School COPYRIGHT © by T.A. Nugent 2015 An El Paso Odyssey by TAFARI A. N UGENT, BA Creative Writing Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Department of Creative Writing THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO MAY 2015 Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................vi Section I- In the Absence of Narration ............................................................................vii -

Download English Translation of Act

This is the translation of ACT TWO of LA BOHÉME (Transcript of the full Opera available here: https://www.opera-arias.com/puccini/la- bohème/libretto/english/ ) Cast: MIMI, a seamstress (Soprano) RODOLFO, a poet (Tenor) MARCELLO, a painter (Baritone) COLLINE, a philosopher (Bass) SCHAUNARD, a musician (Baritone) BENOIT, a landlord (Bass) MUSETTA, a grisette (Soprano) ALCINDORO, a state councellor and follower of Musetta (Bass) PARPIGNOL, an itinerant toy vendor (Tenor) CUSTOM-HOUSE SERGEANT (Bass) CHORUS Students, Working girls, Bourgeois, Shopkeepers, Street vendors, Soldiers, Waiters, Children, Tavern drinkers, Scavengers, Carters, Milkmaids, Peasant women ACT TWO (SECOND TABLEAU) Later the same evening, outside the Café Momus in the Latin Quarter; the café is so crowded that customers have to be accommodated at tables outside. All round them street vendors are shouting their wares. STREET VENDORS variously Oranges, dates! Hot chestnuts! Trinkets, crosses! Nougat! Whipped cream! Fruit pies, ho! Toffees! Flowers for the pretty girls! Fruit pies! Whipped cream! Finches, sparrows! dates! URCHINS Oranges, trinkets! Hot chestnuts and toffees! Nougat! Come on, let's hurry, come on, hurry! MEN What crowds! What a din! WOMEN Oh, what a lot of people! STUDENTS to midinettes Come on, let's run! Stick close to me! What a row! Come on, let's run! CROWD Make way! Let's run! STREET VENDORS, URCHINS repeating as before Hot chestnuts! Cream, nougat! etc. Coconut milk! Fruit pies! Ho! etc., etc. CROWD What a crowd! Let's be off! Oh! … Let us pass! VARIOUS -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Daylyt All Albums Download Daylyt

daylyt all albums download Daylyt. Song suggestions: Day Electronica, The Daytrix, Last Breath, Free Ya Mind (with Metta World Peace, Noble King Ali & Loaded Lux), Letter to Obama, Ark, 2 Mics, First Breath, Dear Father, Dr. Sebi Tribute, High For Hours (J. Cole Remake), I Am Spawn, Afeni Shakur RIP, Threatening Nature (Ab-Soul Remake), Pokemon Lives Matter, Survival of the Fit (with Mr2theP), If I owned a Planet (with Mr2theP), Canvis, Giraffes (with Hopsin), Mural, Everybody Gotta Die, Freedom, Nobody, Lucifer, Why, Merkaba, Daysaprock. Listen on Apple Music: Projects to check out: Other projects: The Key Maker, Lucifer. Buy his music on iTunes: Social media: Quotes: You gave us a general, picked him A diamond in the rough and all the men would roll with him If I could go back in time I’d be there at the row with him Front row with him, roll with you Screamin’ “this for my panthers, this one’s for Huey Newton” We went from panthers, now everybody is panther fans From Huey Newton to Cam Newton, the plan advanced We gotta finish what you started, finish what you taught him Finish what you taught me. – Afeni Shakur RIP. Get plugged to the cable unable to get through The hole that we’re facin’, they label you Then put you into the system, they schoolin’ the victim The more you think you smart the more that you get dumb The history books that you pick up Is his storybooks that you pick up A hiccup, a stick-up, the hick up the ass If you ask me if I believe in this new bible No, I believe in our survival The oddessey, gotta see this is our rival Arrival, this mission is vital Dismissin’ our tribal, but I know the gift is inside you To get to the gift is the veinal To find it and fine tune it to lift up the pineal gland This is the final chance, I hope that I advance. -

Morning Prayer, Rite II

Morning Prayer, Rite II ST. JAMES’S EPISCOPAL CHURCH July 5, 2020 | 10:00 a.m. Fifth Sunday after Pentecost Prelude Toccatina, Psalm 42 (Comfort ye my people) Henry Woodward Comfort, comfort ye my people, speak ye peace, thus saith our God. Comfort those who sit in darkness mourning ’neath their sorrows’ load. Choral Introit: Kyrie Leo Sowerby Lord, have mercy upon me. Christ have mercy upon me. Lord, have mercy upon me. Prayer Almighty God, our heavenly Father, whose Son, Jesus Christ, came to cast a fire upon the earth, grant that by the prayers and songs of your faithful people, a fire of love may be kindled in us, passing from soul to soul until all the hardness of our hearts is melted away; through Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen. Chorale Harmonization, Psalm 42 David N. Johnson Make ye straight what long was crooked, make the rougher places plain; let your hearts be true and humble, as befits his holy reign. Hymn 436: Truro, “Lift up your heads, ye mighty gates” 1 Lift up your heads, ye mighty gates; behold, the King of glory waits; the King of kings is drawing near; the Savior of the world is here! 2 Fling wide the portals of your heart; make it a temple, set apart from earthly use for heaven's employ, adorned with prayer and love and joy. 3 Redeemer, come, with us abide; our hearts to thee we open wide; let us thy inner presence feel; thy grace and love in us reveal. 4 Thy Holy Spirit lead us on until our glorious goal is won; eternal praise, eternal fame be offered, Savior, to thy name Opening Sentences Book of Common Prayer, page 78 The Confession of Sin and Absolution The Officiant says to the people Dearly beloved, we have come together in the presence of Almighty God our heavenly Father, to set forth his praise, to hear his holy Word, and to ask, for ourselves and on behalf of others, those things that are necessary for our life and our salvation. -

Daily Reprieve

Dear Friends, We are delighted to present to you this latest edition of The Daily Reprieve. This issue remembers the difficult times our pets have been though in a thoughtful piece by Mark L. We also have some powerful insights into slips, which reminds us all how precious each 24 hours is. Plus some AA humour and wonderful poetry and art. Please keep sending us your creative contributions. Whether written or sketched, told, shared, or even sung (we haven’t printed a song yet, so get writing fellows!) we are loving all the different expressive ways we can share our experiences with this disease. As always in the back of the newsletter, you can find updates on available service positions throughout AA, the weekly meeting list, round-ups around the region and more. Please send your articles, artwork, tips, stories… songs… to: [email protected]. In Service, Marnie H, Eric C, Lisa G, Mark L. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in the articles submitted to the Daily Reprieve are those of the contributor, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Alcoholics Anonymous. IN THIS ISSUE … • Letter From the Editors • Table of Contents • A Personal Journey Through The Steps • Learning The Steps Vs Living The Steps • Recovery Is A Beautiful Thing • How to: Survive a Family Visit • My Ten Year Journey In Recovery • To Pets • Attention, Love & Consolation • The 80 Day Relapse • Slips and Human Nature • Secrets Go Clink • Poem by Erika • Only Joking.. • AA Certain Type of Humour • Upcoming A.A. Events, Conventions and Roundups • Singapore A.A. -

G:\Pocket Hymn Book (1787)

Modernized text Pocket Hymn Book (1787)1 [Baker List, #444] Editorial Introduction: In 1780 John Wesley issued A Collection of Hymns for the People Called Methodists. This was the largest collection that he ever published (with 525 hymns), and Wesley clearly desired that it would become the standard text of his Methodist people for private use and in their society gatherings.2 One major obstacle stood in the way of this desire—the cost of the volume, at 4 shillings. It was in part because many of his people could not afford this cost that Wesley continued to reprint Select Hymns (1765), with editions in 1780, 1783, and 1787, which was less than a third the length of the 1780 Collection, and sold for 1 shilling, six pence. But Select Hymns did not mirror well the content of the 1780 Collection, lacking even such Methodist favourites as “O for a Thousand Tongues.” This created an opportunity for Robert Spence, a bookseller with Methodist connections in York , to offer another solution. In 1781 he published an abridgement of Wesley’s 1780 Collection, reducing it by two-thirds (to 174 hymns), while retaining the most popular hymns among Methodists.3 Spence took this step without approval, and drew Wesley’s displeasure.4 But since he was not an itinerant preacher, Spence was not accountable to injunctions by Conference against publishing materials without Wesley’s approval.5 While his 1781 publication had limited success, Spence reframed it in 1783 in two ways that greatly increased its popularity. First, he added about fifty hymns by other authors popular in evangelical circles.