Final Thesis Combined.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KAWS Media Release

KAWS Media release 6 February–12 June 2016 Longside Gallery and open air Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) presents the first UK museum exhibition by KAWS, the renowned American artist, whose practice includes painting, sculpture, printmaking and design. The exhibition, in the expansive Longside Gallery and open air, features over 20 works: commanding sculptures in bronze, fibreglass, aluminium and wood alongside large, bright canvases immaculately rendered in acrylic paint – some created especially for the exhibition. The Park’s historically designed landscape becomes home to a series of monumental and imposing sculptures, including a new six-metre-tall work, which take KAWS’s idiosyncratic form of almost-recognisable characters in the process of growing up. Brooklyn-based KAWS is considered one of the most relevant artists of his generation. His influential work engages people across the generations with contemporary art and especially opens popular culture to young and diverse audiences. A dynamic cultural force across art, music and fashion, KAWS’s work possesses a wry humour with a singular vernacular marked by bold gestures and fastidious production. In the 1990s, KAWS conceived the soft skull with crossbones and crossed-out eyes which would become his signature iconography, subverting and abstracting cartoon figures. He stands within an art historical trajectory that includes artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Jeff Koons, developing a practice that merges fine art and merchandising with a desire to communicate within the public realm. Initially through collaborations with global brands, and then in his own right, KAWS has moved beyond the sphere of the art market to occupy a unique position of international appeal. -

SSAH Journal 2006 - Art, Art History & Research in Dundee

SSAH Journal 2006 - Art, Art History & Research in Dundee Dr Ailsa Boyd JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH SOCIETY FOR ART HISTORY VOLUME XI 2006 CALL FOR PAPERS The 2006 edition of the Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History will be focused on the City of Dundee and will be guest-edited by Matthew Jarron, Curator of Museum Services at the University of Dundee. There will be two main themes to this special issue: 1) Art in Dundee We welcome any paper exploring the history of art in Dundee. This might be focused on the work of a specific artist (such as McIntosh Patrick, Alberto Morrocco or David Mach) or an artistic group or collaboration (such as the Dundee Graphic Arts Association or Dalziel + Scullion). We are interested in papers on the development of art exhibitions (from the Victoria Galleries to DCA), aspects of art education (from the Watt Institute to Duncan of Jordanstone College), art patronage (Orchar, Boyd et al) or of art publishing (the Beano being the most celebrated example!). Some of the papers for this section will be drawn from the conference Art in Dundee 1880-1920 held at the University of Dundee in 2005. We would therefore particularly encourage submissions dealing with subjects outwith this period. 2) Art History & Research in Dundee Dundee is now the only University to host a Chair of the History of Scottish Art and has recently established a Centre for the Study of Modern & Contemporary Scottish Art. We are keen to showcase the research work of art historians, curators and artists based in Dundee, whatever your area of interest. -

DAVID MACH New York, NY 10014

82 Gansevoort Street DAVID MACH New York, NY 10014 p (212) 966-6675 Born 1956, Methil, Fife, Scotland allouchegallery.com Lives and works in London, UK 1974-1979 Duncan of Jordanston College of Art and Design, Dundee, Scotland 1979-1982 Royal Academy of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 The Paper to Prove It, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, UK 2019 Waves, Newpaper Installation, Chester Cathedral, Chester, UK 2018 Signs of Life, Collaboration Mach/Adesina, Bolee Gallery, London, UK 2018 Rock n’ Roll, Newspaper Installation, Galway, Ireland 2018 Against the Tide, Newspaper Installation, CassArt, Glasgow, UK 2017 First Station Centre, Against the Tide, Outwith Festival, Dunfermline, UK 2017 Mach Goes Commando, Royal Engineers Museum, Gillingham, UK 2017 David Mach, Alternative Facts, Dadiani Fine Art, London, UK 2016 Golgotha, Chester Cathedral, Chester, UK 2016 Mach Goes Commando, Shetlands Art Development Agency, Shetlands, UK 2015 Mach Goes Commando, DLI Museum, Durham, UK 2015 Precious Light, Center of Turin, Italy 2013 Precious Light, Palazzo Frangini, Venice, Italy 2013 David Mach, New Works, Forum Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Mach-Mania: The David Mach Show, Opera Gallery, Hong Kong 2012 David Mach-Precious Light, Galway, Ireland 2011 David Mach-Precious Light, City Arts Centre, Edinburgh, UK 2010 Iconography, Opera Gallery, London, UK 2009 Mach, Opera Gallery, Geneva, Switzerland 2008 Breaking Images, The Cat Street Gallery, Hong Kong 2008 Size Doesn’t Matter, Art Center de Vishal, Haarlem, The Netherlands 2007 David -

Towards an Understanding of the Contemporary Artist-Led Collective

The Ecology of Cultural Space: Towards an Understanding of the Contemporary Artist-led Collective John David Wright University of Leeds School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2019 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of John David Wright to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 1 Acknowledgments Thank you to my supervisors, Professor Abigail Harrison Moore and Professor Chris Taylor, for being both critical and constructive throughout. Thank you to members of Assemble and the team at The Baltic Street Playground for being incredibly welcoming, even when I asked strange questions. I would like to especially acknowledge Fran Edgerley for agreeing to help build a Yarn Community dialogue and showing me Sugarhouse Studios. A big thank you to The Cool Couple for engaging in construcutive debate on wide-ranging subject matter. A special mention for all those involved in the mapping study, you all responded promptly to my updates. Thank you to the members of the Retro Bar at the End of the Universe, you are my friends and fellow artivists! I would like to acknowledge the continued support I have received from the academic community in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies. -

Download Publication

CONTENTS History The Council is appointed by the Muster for Staff The Arts Council of Great Britain wa s the Arts and its Chairman and 19 othe r Chairman's Introduction formed in August 1946 to continue i n unpaid members serve as individuals, not Secretary-General's Prefac e peacetime the work begun with Government representatives of particular interests o r Highlights of the Year support by the Council for the organisations. The Vice-Chairman is Activity Review s Encouragement of Music and the Arts. The appointed by the Council from among its Arts Council operates under a Royal members and with the Minister's approval . Departmental Report s Charter, granted in 1967 in which its objects The Chairman serves for a period of five Scotland are stated as years and members are appointed initially Wales for four years. South Bank (a) to develop and improve the knowledge , Organisational Review understanding and practice of the arts , Sir William Rees-Mogg Chairman Council (b) to increase the accessibility of the art s Sir Kenneth Cork GBE Vice-Chairma n Advisory Structure to the public throughout Great Britain . Michael Clarke Annual Account s John Cornwell to advise and co-operate wit h Funds, Exhibitions, Schemes and Awards (c) Ronald Grierson departments of Government, local Jeremy Hardie CB E authorities and other bodies . Pamela, Lady Harlec h Gavin Jantje s The Arts Council, as a publicly accountable Philip Jones CB E body, publishes an Annual Report to provide Gavin Laird Parliament and the general public with an James Logan overview of the year's work and to record al l Clare Mullholland grants and guarantees offered in support of Colin Near s the arts. -

Press Release Yorkshire Sculpture Park Set to Welcome Visitors Back This Spring

Press Release Yorkshire Sculpture Park set to welcome visitors back this spring As spring brings the promise of brighter days ahead, Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) has unveiled its plans to continue its phased reopening in line with the government roadmap, and welcome visitors back to appreciate and enjoy a remarkable collection in an exceptional landscape. YSP is a unique cultural destination, museum and registered charity in Wakefield, welcoming diverse audiences across its 500 acres where around 100 sculptures are sited in formal gardens, parkland, woods and around two lakes. Serving ongoing cultural learning, physical activity and mental wellbeing, throughout 2021, new exhibitions and artist projects will be launched, with narratives of identities and histories, and a material focus on textiles, photography, ceramics and the natural world. From 12 April, the shop in the YSP Centre will reopen, displaying a stunning collection of ceramic tiles and prints as part of Alison Milner’s new exhibition, Decorative Minimalist, inspired by YSP. After more than a year of closure due to COVID-19, The Weston will begin to reopen its doors. From 27 April, The Weston shop will welcome customers back to browse an exciting new range of products, and The Restaurant will open for outdoor dining on the same day. Indoor restaurant seating will follow on 18 May, complete with a revamped menu for spring. Booking is advised and reservations will be taken from 12 April. Please phone +44 (0)1924 930004 or email [email protected] to reserve a table. The Weston will be open Tuesday to Sunday and Bank Holidays. -

KAWS Media Release

KAWS Media release OPEn-AIR KAWS SCULPTURES TO REMAIN AT YORksHIRE SCULPTURE PARK Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) is pleased to announce that six sculptures by the renowned American artist KAWS will remain on display until December 2016 giving visitors to the Park a further six months to enjoy the monumental works in the open air. Following the success of the artist’s first UK museum exhibition in YSP’s Longside Gallery and the open air, the six sculptures – SMALL LIE (2013), GOOD INTENTIONS (2015), AT THIS TIME (2013), BETTER KNOWING (2013), FINAL DAYS (2013) and ALONG THE WAY (2013) – will continue to be seen in the Lower Park, beyond the exhibition’s official end date of 12 June 2016. Outdoors, with their outsize and monumental proportions, KAWS’s sculptures bring to mind dystopian cartoon characters; recognisable personalities from childhood who appear to have lost their innocence. Against the Park’s tree line, the group of six works in natural and black-stained wood, measuring between three and 10 metres in height, are simultaneously spectacular and plaintive. Once bright, iconic characters are rendered in disheartened, world-weary Images, left to right: poses; imposing yet full of pathos, they point to an array of psychological SMALL LIE (2013) courtesy the artist, narratives, suggesting compassion, surprise and despair. YSP and Galerie Perrotin. Wood, H1000cm x W464cm x D427.2cm; Brooklyn-based KAWS is considered one of the most relevant artists of his time. GOOD INTENTIONS (2015) Courtesy His influential work engages people across the generations with contemporary the artist and More Gallery. Wood, art and especially opens popular culture to young and diverse audiences. -

Economic Value and Impact of Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Economic Value and Impact of Yorkshire Sculpture Park Final Report October 2011 Carlisle Leicester Suite 7 (Second Floor) 1 Hewett Close Carlyle’s Court Great Glen 1 St Mary’s Gate Leicester Carlisle CA3 8RY LE8 9DW t: 01228 402 320 t: 0116 259 2390 m: 07501 725 114 m: 07501 725115 e: [email protected] e: [email protected] www.dcresearch.co.uk Economic Value and Impact of Yorkshire Sculpture Park: Final Report CONTENTS KEY FINDINGS...........................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ....................................................2 2. KEY QUANTITATIVE ECONOMIC IMPACTS .............................................4 Visitor Impacts .................................................................................4 Employment and Procurement Impacts................................................7 3. ADDITIONAL AND CATALYTIC IMPACTS, AND ADDED VALUE...................9 Education and Learning .....................................................................9 Supporting Local Priorities................................................................ 10 Profile Impacts ............................................................................... 12 Summary and Future Impacts .......................................................... 13 APPENDIX 1: CONSULTEES ....................................................................... 15 APPENDIX 2: GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS ..................................................... 16 Economic Value and Impact of Yorkshire -

Marlborough Gallery

Marlborough DENNIS OPPENHEIM 1938 — Born in Electric City, Washington 2011 — Died in New York, New York The artist lived and worked in New York, New York. Education 1965 — B.F.A., the School of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California 1966 — M.F.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, California Solo Exhibitions 2020 — Dennis Oppenheim, Galerie Mitterand, Paris, France 2019 — Feedback: Parent Child Projects from the 70s, Shirley Fiterman Art Center, The City University of New York, BMCC, New York, New York 2018 — Violations, 1971 — 1972, Marlborough Contemporary, New York, New York Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo, Sweden 2016 — Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York 2015 — Wooson Gallery, Daegu, Korea MAMCO, Geneva, Switzerland Halle Nord, Geneva, Switzerland 2014 — MOT International, London, United Kingdom Museo Magi'900, Pieve di Cento, Italy 2013 — Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, United Kingdom Museo Pecci Milano, Milan, Italy Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom Marlborough 2012 — Centro de Arte Palacio, Selected Works, Murcia, Spain Kunst Merano Arte, Merano, Italy Haines Gallery, San Francisco, California HaBeer, Beersheba, Israel 2011 — Musée d'Art moderne Saint-Etienne Metropole, Saint-Priest-en-Jarez, France Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Quebec, Canada The Carriage House, Gabarron Foundation, New York, New York 2010 — Thomas Solomon Gallery, Los Angeles, California Royale Projects, Indian Wells, California Buschlen Mowatt Galleries, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Galleria Fumagalli, Bergamo, Italy Gallerie d'arts Orler, Venice, Italy 2009 — Marta Museum, Herford, Germany Scolacium Park, Catanzaro, Italy Museo Marca, Catanzarto, Italy Eaton Fine Art, West Palm Beach, Florida Janos Gat Gallery, New York, New York 2008 — Ace Gallery, Beverly Hills, California 4 Culture Gallery, Seattle, Washington Edelman Arts, New York, New York D.O. -

Forming Sculpture, Provisional Programme 26 – 27 June 2018, Leeds

Association for Art History Summer Symposium 2018 (Re-)Forming Sculpture, Provisional Programme 26 – 27 June 2018, Leeds Tuesday 26 June, The Hepworth Wakefield 10.00-10.15 Registration and Refreshments 10.15-10.30 Welcome from Conference Organisers | Gregory Perry, CEO, Association for Art History 10.30-11.45 Session 1: Curating the Sculptural Display Chair: Rebecca Wade • Nicole Cochrane (University of Hull) ‘’The Only Happy Couple I Ever Saw’: Ancient Hermaphrodite Sculptures and their Receptions’ • Helen Goulston (University of Birmingham/Oxford University Museum of Natural History) ‘’The Founders of Natural Knowledge’: Sculpture at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History’ • Amy Harris (University of York/Tate Britain) ‘Wrestling with an Unruly Collection: The Curation of the Sculpture Hall at Tate Britain – 1904 and 1933’ 11.45-11.50 Comfort Break 11.50-1.30 Session 2: Rethinking the Monument Chair: TBC • Stephano Colombo (University of Warwick) ‘Baldassarre Longhena’s Funerary Monument to Doge Giovanni Pesaro and the Rhetoric of the Living Sculpture’ • Ciarán Rua O’Neill (University of York) ‘‘The Old Truth that The Art is One’: Sculpture and Artistic Intermediality from the Nineteeth to Early Twentieth Centuries’ • Clare Fisher (University of St Andrews) ‘Reducktive Art, or What I’ve Learnt from Las Vegas’ • Sooyoung Leam (Courtauld Institute of Art) ‘The Spectres and Spectacles of the Past: Lee Seung-taek’s Non-Sculptures and Monuments’ 1.30-2.20 Lunch 2.20-3.15 Session 3: Yorkshire: Sculpting a Legacy Chair: Rowan Bailey -

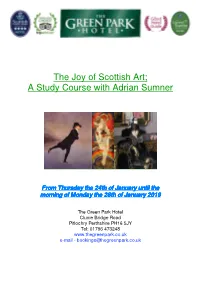

The Joy of Scottish Art; a Study Course with Adrian Sumner

The Joy of Scottish Art; A Study Course with Adrian Sumner From Thursday thethethe 24th ofofof January until thethethe morning ofofof MondMondayayayay thethethe 28th ofofof January 2019 The Green Park Hotel Clunie Bridge Road Pitlochry Perthshire PH16 5JY Tel: 01796 473248 www.thegreenpark.co.uk e-mail - [email protected] The Joy of Scottish Art From Thursday thethethe 24th ofofof January until thethethe morning ofofof Monday thethethe 28th ofofof January 2019 A series of six lectures comprising; * An Outline History of Art in Scotland * Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow School * Mackintosh, Arts and Crafts and International Art Nouveau * Modernism, Glasgow Boys and Girls, Colourists, and the Celtic Revival * Contemporary Scottish Art * Great Scottish Collections All illustrated with colour images in Powerpoint presentations. Suitable for all levels of student, plus those who simply love the subject. Thursday thethethe 24th ofofof JanuarJanuaryyyy So as to make the most of your day, please feel free to arrive any time from mid-morning onwards. Complimentary tea, coffee, and biscuits, will be available in the main lounge. 6.00p6.00pmmmm. The first organised activity will be a sherry reception in room 585858 ononon thethethe ground floor ofofof thethethe Tower Wing . This will give you an opportunity to meet your fellow students as well as your tutor Adrian Sumner. From 666.6...30303030pmpmpmpm --- 8.30pm8.30pm.... A four course dinner will be served in the dining room, followed by coffee and shortbread in the lounges. Friday thethethe 25th ofofof January 8.30am --- 9.45am. A full Scottish breakfast will be served in the dining room. -

David Mach RA 8 Havelock Walk, Forest Hill, London, UK Landline +44(0)2086995659 / Mobile +44(0)7947661500 / [email protected]

David Mach RA 8 Havelock Walk, Forest Hill, London, UK Landline +44(0)2086995659 / Mobile +44(0)7947661500 / [email protected] / www.davidmach.com BIOGRAPHY 1956 Born in Methil, Fife (Scotland) 1974/79 Duncan of Jordanston College of Art, Dundee (Scotland) 1975 Pat Holmes Memorial Prize 1976 Duncan of Drumfork Travelling Scholarship 1977 SED minor travelling scholarship 1978 SED major travelling scholarship 1979/82 Royal College of Art (RCA), London. 1982 RCA Drawing Prize 1988 Nominated for the Turner Prize, Tate Gallery, London 1992 Won Lord Provost’s Award, RGI, Glasgow 1998 Elected Member of the Royal Academy of Arts 1999 Visiting Professor, Sculpture Department, Edinburgh College of Art 2000 Appointed Professor of Sculpture, Royal Academy Schools, London 2002 Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Dundee University 2004 Made Honorary Member of the Royal Scottish Academy First Visiting Professor of Inspiration and Discovery at the University of Dundee (Scotland) 2006-2010 Elected to the board of the National Portrait Gallery 2011 Bank of Scotland Herald Angel Award 2011 winner for Precious Light 2011 Glenfiddich Spirit of Scotland Award for Art SELECTED PUBLIC ART PROJECTS & COMMISSIONS 2012 The Vinadio “Giants”, VIAPAC Project, Regione Piemonte, Italy 2002 Collage Portrait of Glasgow commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, Glasgow 2000 Unveiled “Good Guys, Bad Guys” & “Scamble”, sculptures commissioned by Chesterfield Council, UK 1999 Installed “A National Portrait”, a 70m x 3m collage of Britain, commissioned by the NMEC