Joint Authors: When Are Collaborators in a Musical Work Entitled to Share in the Copyright of the Work?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cord Weekly

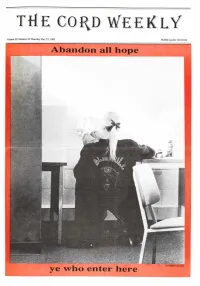

THE CORD WEEKLY Volume 29, Number 25 Thursday Mar. 23,1989 Wilfrid Laurier University Abandon all hope ye who enter here Cord Photo: Liza Sardi The Cord Weekly 2 Thursday, March 23,1989 THE CORD WEEKLY |1 keliv/f!rent-a-car ; SAVE $5.00 ! March 23,1989 Volume 29, Number 25 ■ ON ANY CAR RENTAL ■ I Editor-in-Chief Cori Ferguson ■ NEWS Editor Bryan C. Leblanc Associate Jonathan Stover Contributors Tim Sullivan Frances McAneney COMMENT ■ ■ Contributors 205 WEBER ST. N. Steve Giustizia l 886-9190 l FEATURES Free Customer Pick-up Delivery ■ Editor vacant and Contributors Elizabeth Chen ENTERTAINMENT Editor Neville J. Blair Contributors Dave Lackie Cori Cusak Jonathan Stover Kathy O'Grady Brad Driver Todd Bird SPORTS Editor Brad Lyon Contributors Brian Owen Sam Syfie Serge Grenier Lucien Boivin Raoul Treadway Wayne Riley Oscar Madison Fidel Treadway Kenneth J. Whytock Janet Smith DESIGN AND ASSEMBLY Production Manager Kat Rios Assistants Sandy Buchanan Sarah Welstead Bill Casey Systems Technician Paul Dawson Copy Editors Shannon Mcllwain Keri Downs Contributors \ Jana Watson Tony Burke CAREERS Andre Widmer 112 PHOTOGRAPHY Manager Vicki Williams Technician Jon Rohr gfCHALLENGE Graphic Arts Paul Tallon Contributors Liza Sardi Brian Craig gfSECURITY Chris Starkey Tony Burke J. Jonah Jameson Marc Leblanc — ADVERTISING INFLEXIBILITY Manager Bill Rockwood Classifieds Mark Hand gfPRESTIGE Production Manager Scott Vandenberg National Advertising Campus Plus gf (416)481-7283 SATISFACTION CIRCULATION AND FILING Manager John Doherty Ifyou want theserewards Eight month, 24-issue CORD subscription rates are: $20.00 for addresses within Canada inacareer... and $25.00 outside the country. Co-op students may subscribe at the rate of $9.00 per four month work term. -

The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive A Change is Gonna Come: The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies And Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Laws in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kurt Dahl © Copyright Kurt Dahl, September 2009. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan 15 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A6 i ABSTRACT The purpose of my research is to examine the music industry from both the perspective of a musician and a lawyer, and draw real conclusions regarding where the music industry is heading in the 21st century. -

Martha Sturdy and Walter Murch Receive Eci Honorary Doctor of Letters

/ / p u b l i s h e d Fall 06 Visions> // published by emily carr institute foundation + development office // President’s New CIRO Message appointed 02 02 New Director ECI at for IDS SIGGRaPH 03 03 Delectable Emily award martha sturdy Designs Winner and walter murch 06 07 receive eci honorary doctor of letters lEfT To RIGHT: ECI BoaRD CHaIR, DR. GEoRGE pEDERSEN, walTER MURCH, Governor General, and is a member of the Royal > Animation Grad wins MaRTHa STURDy aND ECI pRESIDENT DR. RoN BURNETT. Canadian academy of arts. Her work has been $20,000 award published in international magazines such as ECI Gets matching Grant at the Institute’s 77th convocation on May 6th, Architectural Digest, Metropolitan Home, and Vogue. 2006, Martha Sturdy and walter Murch were each Every graduating student hopes their grad conferred an Honorary Doctor of letters degree. walter Murch is an award-winning film editor and project will launch their careers. For Joel sound mixer, based in California. He received an Furtado, his big break came in the form of an ECI alumna, Martha Sturdy is an internationally- academy award for best sound for Apocalypse Now, Electronic Arts’ Reveal 06: Canadian 3D renowned leading designer of furniture, home two British academy awards in 1975 for film editing Animation Showdown. accessories, jewelry and wall sculptures. Based in and sound mixing for The Conversation, as well as Congratulations to Joel, B.C., she is known for creating distinctive artwork numerous nominations from both academies. walter whose animated short using casting resin, brass and steel that is that is directed and co-wrote the film return to oz in 1985, film Tree for Two bold, clean and simple. -

Licensing Rules Repertoire Definition

CIS14-0091R40 Source language: English 30/06/2021 The most recent updates are marked in red Licensing Rules Repertoire Definition This document sets out the repertoire definitions claimed directly by European Licensors in Europe and in some cases outside Europe. the repertoires are defined per Licensor / territory / types of on-line exploitations and DSPs with starting dates when necessary. Differences with the last version of this document are written in red. The document is a snap shot of the current information available to the TOWGE and is updated on an ongoing basis. Please note that the repertoires are the repertoires applied by the Licensors and are not precedential nor can they bind other licensing entities. The applicable repertoire will always be the one set out in the respective representation agreement between Licensors. Towge best practices on repertoires update are: • to communicate an update preferably 3 months but no later than 1 month before the starting period of the repertoire in order to allow enough time for Towge to communicate a new "repertoire definition document" to both Licensors and Licensees, which will allow these to adapt their programs accordingly • to not re-process invoices that have already been generated by Licensors and processed by Licensees Date of Publication Repertoire Licensing Body Pan-European Repertoire Definition DSPs Use Type Start Date Notes End Date Contact licensing Apr-19 WCM Anglo-American ICE Warner Chappell Music Publishing repertoire (mechanical and CP rights) licensable under the PEDL arrangement where the 7 Digital Ltd all digital 01/01/2010 Steve.Meixner repertoire author/composer of the Musical Work (or part thereof as applicable) is non-society or a member of PRS, IMRO, ASCAP, BMI, Amazon Music Unlimited (Steve.Meixner@u SESAC, SOCAN, SAMRO or APRA. -

Australian School of Business

Australian School of Business Marketing MARK6021 Integrated Marketing Communications Master of Marketing Elective Course 3 UOC (units of credit) Course Outline Semester 2, 2013 Part A: Course-Specific Information Part B: Key Policies, Student Responsibilities and Support MARK6021 Integrated Marketing Communications Table of Contents 1 1 STAFF CONTACT DETAILS 4 2 COURSE DETAILS 4 2.1 Teaching Times and Locations 4 2.2 Units of Credit 4 2.3 Summary of Course 4 2.4 Course Aims and Relationship to Other Courses 5 2.5 Student Learning Outcomes 5 3 LEARNING AND TEACHING ACTIVITIES 7 3.1 Approach to Learning and Teaching in the Course 7 3.2 Learning Activities and Teaching Strategies 8 4 ASSESSMENT 8 4.1 Formal Requirements 8 4.2 Assessment Details 8 9 4.3 Assignment Submission Procedure 16 17 5 COURSE RESOURCES 17 . Shimp, TA, Andrews, JC (2013). Advertising, promotion, and other aspects of integrated marketing communications. Mason: Cengage. 17 LIBRARY DATABASES VIA SIRIUS : 18 HTTP://SIRIUS.LIBRARY.UNSW.EDU.AU 18 GOOGLE SCHOLAR: 18 6 COURSE EVALUATION AND DEVELOPMENT 19 7 COURSE SCHEDULE 20 PART B: KEY POLICIES, STUDENT RESPONSIBILITIES AND SUPPORT 23 1 PROGRAM LEARNING GOALS AND OUTCOMES 23 2 ACADEMIC HONESTY AND PLAGIARISM 24 3 STUDENT RESPONSIBILITIES AND CONDUCT 24 3.1 Workload 24 3.2 Attendance 25 3.3 General Conduct and Behaviour 25 3.4 Occupational Health and Safety 25 3.5 Keeping Informed 25 4 SPECIAL CONSIDERATION AND SUPPLEMENTARY EXAMINATIONS 25 MARK6021 Integrated Marketing Communications 2 5 STUDENT RESOURCES AND SUPPORT 26 MARK6021 Integrated Marketing Communications 3 PART A: COURSE-SPECIFIC INFORMATION 1 STAFF CONTACT DETAILS Lecturer in Charge: Nicole Lasky Nicole Lasky has a strong background in both university teaching and industry. -

BC's Music Sector

BC’s Music Sector FROM ADVERSITY TO OPPORTUNITY www.MusicCanada.com /MusicCanada @Music_Canada BC’S MUSIC SECTOR: FROM ADVERSITY TO OPPORTUNITY A roadmap to reclaim BC’s proud music heritage and ignite its potential as a cultural and economic driver. FORWARD | MICHAEL BUBLÉ It’s never been easy for artists to get a start in We all have a role to play. Record labels and music. But it’s probably never been tougher other music businesses need to do a better than it is right now. job. Consumers have to rethink how they consume. Governments at all levels have to My story began like so many other kids recalibrate their involvement with music. And with a dream. I was inspired by some of successful artists have to speak up. the greatest singers – Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett and Frank Sinatra – listening to my We all have to pull together and take action. grandfather’s record collection while growing up in Burnaby. I progressed from talent I am proud of the fact that BC gave me a competitions, to regular shows at local music start in a career that has given me more venues, to a wedding gig that would put me than I could have ever imagined. After in the right room with the right people – the touring around the world, I am always right BC people. grateful to come home to BC where I am raising my family. I want young artists to When I look back, I realize how lucky I was. have the same opportunities I had without There was a thriving music ecosystem in BC having to move elsewhere. -

Martin Gay Producer Paper Nathan Adam Mark Endert Mark Endert

Martin Gay Producer Paper Nathan Adam Mark Endert Mark Endert grew up idolizing producers rather than the musicians admired by his peers. “...Even when I was very young I wanted to work in the behind-the-scenes part of record making.”2, reflects Endert in his Nettwerk profile online. From the beginning, Endert chased his dreams in the record-making process and the recordings themselves, and it was this single- minded dedication that drove him to his success, as well as the doorstep of a nearby studio that would be very impressed with his well-educated interview. At the age of 17, he began working at The Village Recorder studio in LA as “tea boy”2. It was not long, however, before Endert was setting up Sony Music Studios in LA and took the role of chief engineer. He took to a freelance work strategy soon after his “claim to fame” work on Fiona Apple’s debut album “Tidal”2. Soon, he was working with Madonna, becoming a widely-known producer in the industry. Like many widely-successful producers, Mark Endert wears many hats. His resume includes roles under such titles as Producer, Co-Producer, Mixer, Recordist, and Additional Production1. In a “Sound On Sound” article from Sept. 2007, Endert was praised for his versatility and involvement in Maroon 5’s blahhhh single from their second album, “It Won’t Be Long Before Soon”. As Producer, Co-Producer, and Mixer, Endert was a very significant influence on the multi-platinum album. Mark began to take and increased interest in mixing after working on the production end for the majority of his early career. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 4-2-2009 The aC rroll News- Vol. 85, No. 19 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 85, No. 19" (2009). The Carroll News. 788. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/788 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Russert Fellowship Tribe preview NBC creates fellowship in How will Sizemore and honor of JCU grad, p. 3 the team stack up? p. 15 THE ARROLL EWS Thursday,C April 2, 2009 Serving John Carroll University SinceN 1925 Vol. 85, No. 19 ‘Help Me Succeed’ library causes campus controversy Max Flessner Campus Editor Members of the African The African American Alliance had to move quickly to abridge an original All-Stu e-mail en- American Alliance Student Union try they had sent out requesting people to donate, among other things, copies of old finals and mid- Senate votes for terms, to a library that the AAA is establishing as a resource for African American students on The ‘Help Me administration policy campus. The library, formally named the “Help Me Suc- Succeed’ library ceed” library, will be a collection of class materials to close main doors and notes. The original e-mail that was sent in the March to cafeteria 24 All-Stu, asked -

Counting the Music Industry: the Gender Gap

October 2019 Counting the Music Industry: The Gender Gap A study of gender inequality in the UK Music Industry A report by Vick Bain Design: Andrew Laming Pictures: Paul Williams, Alamy and Shutterstock Hu An Contents Biography: Vick Bain Contents Executive Summary 2 Background Inequalities 4 Finding the Data 8 Key findings A Henley Business School MBA graduate, Vick Bain has exten sive experience as a CEO in the Phase 1 Publishers & Writers 10 music industry; leading the British Academy of Songwrit ers, Composers & Authors Phase 2 Labels & Artists 12 (BASCA), the professional as sociation for the UK's music creators, and the home of the Phase 3 Education & Talent Pipeline 15 prestigious Ivor Novello Awards, for six years. Phase 4 Industry Workforce 22 Having worked in the cre ative industries for over two decades, Vick has sat on the Phase 5 The Barriers 24 UK Music board, the UK Music Research Group, the UK Music Rights Committee, the UK Conclusion & Recommendations 36 Music Diversity Taskforce, the JAMES (Joint Audio Media in Education) council, the British Appendix 40 Copyright Council, the PRS Creator Voice program and as a trustee of the BASCA Trust. References 43 Vick now works as a free lance music industry consult ant, is a director of the board of PiPA http://www.pipacam paign.com/ and an exciting music tech startup called Delic https://www.delic.net work/ and has also started a PhD on gender diversity in the UK music industry at Queen Mary University of London. Vick was enrolled into the Music Week Women in Music Awards ‘Roll Of Honour’ and BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour Music Industry Powerlist. -

Gardner Beats Rival in Mayoral Election

Today's A four-star weather: All-American Mostly sunny. newspaper Highs in the low 60s. Vol. 115 No. 23 Student Center, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware 19716 Friday,Apri114, 1989 Gardner beats rival ·Plus/ • in mayoral election ffilllUS by Wendy Pickering paign finished. "I'll be a long time forgetting Staff Reporter "Quite frankly, I'm not as it," he added. "The loss was slated happy tonight as I could be deserved." City Councilman Ron because I'm still a little miffed But Miller said Tuesday Gardner (District 5) swept the and disgusted over what has night that he does not harbor Newark mayoral elections happened in the last week," bl;ld feelings about the cam for '90 Tuesday with 2,024 votes, Gardner said. paign. Harold F. Godwin easily defeating rival Councilman Ed Miller had recently accused "It was a hard-fought race defeated university math pro Miller (District 3) by a margin Gardner of paying transfer and I look forward to working fessor David L. Colton with by Kathy Hartman of more than 2-to-1. taxes only on the land where he with Mr. Gardner on the 800 votes to 3 10. · Staff Reporter University student Scott built his house and taking a Council,~' Miller said. Godwin said he has an A tentative date of fall 1990 Feller (AS 90) grabbed only 55 consultant job with the builder, The race for City Council, in aggressive agenda facing him has been set for the implementa votes. causing a "conflict of interest." District 1 was uneventful in and is anxious to begin work. -

A&R Update December 1-2-3-4 GO! RECORDS 423

A&R Update December 1-2-3-4 GO! RECORDS 423 40th St. Ste. 5 Oakland, CA 94609 510-985-0325 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.1234gorecords.com 4AD RECORDS 17-19 Alma Rd. London, SW 18, 1AA, UK E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.4ad.com Roster: Blonde Redhead, Anni Rossi, St. Vincent, Camera Obscura Additional locations: 304 Hudson St., 7th Fl. New York, NY 10013 2035 Hyperion Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90027 825 RECORDS, INC. Brooklyn, N.Y. 917-520-6855 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.825Records.com Styles/Specialties: Artist development, solo artists, singer-songwriters, pop, rock, R&B 10TH PLANET RECORDS P.O. Box 10114 Fairbanks, AK 99710 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.10thplanet.com 21ST CENTURY RECORDS Silver Lake, CA 323-661-3130 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.21stcenturystudio.com Contact: Burt Levine 18TH & VINE RECORDS ALLEGRO MEDIA GROUP 20048 N.E. San Rafael St. Portland, OR 97230 503-491-8480, 800-288-2007 Website: www.allegro-music.com Genres: jazz, bebop, soul-jazz 21ST CENTURY STUDIO Silver Lake, CA 323-661-3130 Email Address: [email protected] Website: www.21stcenturystudio.com Genres: rock, folk, ethnic, acoustic groups, books on tape, actor voice presentations Burt Levine, A&R 00:02:59 LLC PO Box 1251 Culver City, CA 90232 718-636-0259 Website: www.259records.com Email Address: [email protected] 4AD RECORDS 2035 Hyperion Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90027 Email Address: [email protected] Website: www.4ad.com Clients: The National, Blonde Redhead, Deerhunter, Efterklang, St.