Tantra & Erotic Trance Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Providers in India

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 Health Providers in India Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 (ii) Blank Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 Health Providers in India On the Frontlines of Change Editors Kabir Sheikh and Asha George Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 First published 2010 By Routledge 912–915 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2010 Kabir Sheikh and Asha George Typeset by Bukprint India B-180A Guru Nanak Pura, Laxmi Nagar, Delhi 110 092 Printed and bound in India by Sanat Printers 312 EPIP Kundli, Haryana 131 028 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-57977-3 Advance Praise for the Book This excellent collection of new work begins to fill a major gap in our understanding of key features of the Indian health system: Who fill its positions, formal and informal, public and private sector, trained and untrained? What are their motivations, their ideals, and the everyday realities of their experiences? And how do these accommodate to, coalesce with, or conflict with major national health goals? Sheikh and George are to be congratulated for their initiative in stimulating contributors to such a well- constructed volume — one that will undoubtedly set the agenda for health-related policy-relevant research in India over the next decade. -

Tantric Texts Series Edited by Arthur Avalon (John Woodroffe)

KAMAKALAVILASA First Published 1922 Second Edition 1953 Printed by D. V. Syamala Rau, at the Vasanta Press, The Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madias 20 SHRI YANTRA DESCRIPTION OF THE CAKE AS FROM THE CENTRE OUTWARD 1 . Red Point— Sarvfmandamaya. (vv. 22-24, 37, 38). 2. White triangle inverted— Sarvasiddhiprada. (vv. 25, iYi). 3. Eight red triangles -Sarvarogahara. (vv. 29, 40). 4. Ten blue triangles — Sarvaraksakara. (vv. 30, 41). 5. Ten red triangles —Sarvarthasadhaka. (vv. 30, 31, 42). 6. Fourteen blue triangles — Sarvasaubhagyadayaka. (vv. 31, 43). 7. Eight-petalled red lotus — Sarvasarhksobhana. (vv. 33, 41). .S. Sixteen-petalled blue lotus —Sarvasaparipuraka. (vv. 33, 45). 9. Yellow surround —Trailokyamohana. (vv. 34, 46-49). KAMAKALAVILASA BY PUNYANANDANATHA WITH THE COMMENTARY OF NATANANANDANATHA TRANSLATED WITH COMMENTARY BY ARTHUR AVALON WITH NATHA-NAVARATNAMALIKA WITH COMMENTARY MANjUSA Bv BHASKARARAYA 2nd Edition Revised and enlarged Publishers : GANE8H & Co., (MADRAS) Ltd., MADRAS— 17 1958 PUBLISHERS' NOTE The Orientalists' system of transliteration has been followed in this work. 3T a, 3T1 i, I, r, a, f f S u, 5 u, 3£ r, <5 1, c| J " ^ e, ^ ai, oft o, ^ au, m or rh, : h. f k, ^ kh, JTg, ^ gh, S n, Z t, $ th, S d, Z tfh, qT n, ^ t, ^ th, <? d, * dh, ^ n, *Tp, <Jiph, ^b, flbh, ^m, \ y, ^ r, 53 1, W v, ss * s, ^ s, ^ h, 55 1. PREFACE The KamakalA"vila*sa is an important work in S'rlvidya by Punya"nanda an adherent of the Hadimata, who is also the commentator on the Yoginihrdaya, a section called Uttara- catuhs'ati of the great Vamakes'vara Tantra. -

Essays and Addresses on the Śākta Tantra-Śāstra

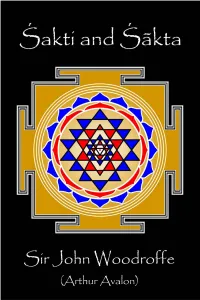

ŚAKTI AND ŚĀKTA ESSAYS AND ADDRESSES ON THE ŚĀKTA TANTRAŚĀSTRA BY SIR JOHN WOODROFFE THIRD EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED Celephaïs Press Ulthar - Sarkomand - Inquanok – Leeds 2009 First published London: Luzac & co., 1918. Second edition, revised and englarged, London: Luzac and Madras: Ganesh & co., 1919. Third edition, further revised and enlarged, Ganesh / Luzac, 1929; many reprints. This electronic edition issued by Celephaïs Press, somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills, and mani(n)fested in the waking world in Leeds, England in the year 2009 of the common error. This work is in the public domain. Release 0.95—06.02.2009 May need furthur proof reading. Please report errors to [email protected] citing release number or revision date. PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION. HIS edition has been revised and corrected throughout, T and additions have been made to some of the original Chapters. Appendix I of the last edition has been made a new Chapter (VII) in the book, and the former Appendix II has now been attached to Chapter IV. The book has moreover been very considerably enlarged by the addition of eleven new Chapters. New also are the Appendices. The first contains two lectures given by me in French, in 1917, before the Societé Artistique et Literaire Francaise de Calcutta, of which Society Lady Woodroffe was one of the Founders and President. The second represents the sub- stance (published in the French Journal “Le Lotus bleu”) of two lectures I gave in Paris, in the year 1921, before the French Theosophical Society (October 5) and at the Musée Guimet (October 6) at the instance of L’Association Fran- caise des amis de L’Orient. -

Tantra As Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe

Julian Strube Tantra as Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe Abstract: John Woodroffe (1865–1936) can be counted among the most influential authors on Indian religious traditions in the twentieth century. He is credited with almost single-handedly founding the academic study of Tantra, for which he served as a main reference well into the 1970s. Up to that point, it is practically impossible to divide his influence between esoteric and academic audiences – in fact, borders between them were almost non-existent. Woodroffe collaborated and exchangedthoughtswithscholarssuchasSylvainLévi,PaulMasson-Oursel,Moriz Winternitz, or Walter Evans-Wentz. His works exerted a significant influence on, among many others, Heinrich Zimmer, Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, Mircea Eliade, Carl Gustav Jung, Agehananda Bharati or Lilian Silburn, as they did on a wide range of esotericists such as Julius Evola. In this light, it is remarkable that Woodroffe did not only distance himself from missionary and orientalist approaches to Tantra, buthealsoidentifiedTantrawithCatholicism and occultism, introducing a univer- salist, traditionalist perspective. This was not simply a “Western” perspective, since Woodroffe echoed Bengali intellectuals who praised Tantra as the most appropriate and authen- tic religious tradition of India. In doing so, they stressed the rational, empiri- cal, scientific nature of Tantra that was allegedly based on practical spiritual experience. As Woodroffe would later do, they identified the practice of Tantra with New Thought, spiritualism, and occultism – sciences that were only re-discovering the ancient truths that had always formed an integral part of “Tantrik occultism.” This chapter situates this claim within the context of global debates about modernity and religion, demonstrating how scholarly approaches to religion did not only parallel, but were inherently intertwined with, occultist discourses. -

Death As Teacher in the Aghori Sect Rochelle Suri California Institute of Integral Studies

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 13 1-1-2010 The iG ft of Life: Death As Teacher in the Aghori Sect Rochelle Suri California Institute of Integral Studies Daniel B. Pitchford Saybrook University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Suri, R., & Pitchford, D. B. (2010). Suri, R., & Pitchford, D. B. (2010). The gift of life: Death as teacher in the Aghori sect. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 29(1), 128–134.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 29 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2010.29.1.128 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Gift of Life: Death As Teacher in the Aghori Sect Rochelle Suri Daniel B. Pitchford California Institute of Integral Studies Saybrook University San Francisco, CA, USA San Francisco, CA, USA This article utilizes the example of the Aghori, with their radical and unique perspective on death, as a challenge to the Western world to live an authentic, present life by maintaining awareness of mortality. Specifically, three main themes are explored: first, a theoretical engagement of the concept of death based on the (Western) philosophy of existentialism, second, a review of the historical origins and philosophy of the Aghori sect, and third, a depiction of the Aghoris as a living example of vigorously accepting death as an inevitability of life. -

Tantric Texts Series Edited by Arthur Avalon (John Woodroffe)

HYMN TO KALI KARPURADI-STOTRA Second Edition 1953 Printed by D. V. Syamala Rau, at the Vasanta Press. The Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras 20 HYMN TO KALI KARPURADI-STOTRA BY ARTHUR AVALON WITH INTRODUCTION AND COMMENTARY By VIMALSNANDA-S'VSMI 2nd Edition Revised and enlarged PUBLISHEES : GANESH & Co., (MADRAS) Ltd., MADRAS— 17 1958 PUBLISHERS* NOTE The Orientalists' system of transliteration has been followed in this work. sr a, «n a, i, i, 3 u, l, * f 5 n, *j r, 5£ f, ^ ^ i ~ ^ e, ^ ai, aft o, ®ft au, m or rh, : h. %k, ^ kh, *{ g, ^ gh, * n, *% c, ^ ch, ^ j, ^ jh, *[ fi, ^ t, $ th, f d, S dh, or n, ^ t, ^ th, ^ d, ^ dh, ^ n, ^p, <J>ph, ^b, <Tbh, ^m, \ y, \ r, 3 1, ^ v, ^ s', ^ s, ^ s, ^ h, 55 I. CONTENTS PAGE . 1-42 Preface .... Hymn to Kali ..... 43-96 . • • • U\ 5Hf^TO%Tf^cP'R .... «*KI«ri\u| SjqtiR5«H^ .... n«raWrarsRWR .... m-m VI PAGE #5Rqi^f <KS$fclWP^ .... \\\ Appendix I ^?T*TflTfa5|iT and g^tf^t . ii sWrgapr: . \M in ?iSTft?fe: . v sqn?qi%Ticram>w^qT5nH35fiq: . JM-tv — By the same Author SHAKTI AND SHAKTA Essays and Addresses on the Shakta Tantra Shastra CONTENTS Section 1.—Introductory—Chapters I—XIII Bharata Dharma—The World as Power (Shakti)—The Tantras—Tantra and Veda Shastras—The Tantras and Religion of the Shaktas— Shakti and Shakta—Is Shakti Force ? —Chlnachara—Tantra Shastras in China—A Tibetan Tantra— Shakti in Taoism—Alleged Conflict of Shastras Sarvanandanatha. Section 2.—Doctrinal—Chapters XIV—XX Chit Shakti—Maya Shakti—Matter and Consciousness Shakti and Maya—Shakta Advaitavada—Creation—The Indian Magna Mater. -

Shiva, the Destroyer and the Restorer

Shiva, The Destroyer and the Restorer DR.RUPNATHJI( DR.RUPAK NATH ) 7 SHIV TATTVA In Me the universe had its origin, In Me alone the whole subsists; In Me it is lost-Siva, The Timeless, it is I Myself, Sivoham! Sivoham! Sivoham! Salutations to Lord Shiva, the vanquisher of Cupid, the bestower of eternal bliss and Immortality, the protector of all beings, destroyer of sins, the Lord of the gods, who wears a tiger-skin, the best among objects of worship, through whose matted hair the Ganga flows. Lord Shiva is the pure, changeless, attributeless, all-pervading transcendental consciousness. He is the inactive (Nishkriya) Purusha (Man). Prakriti is dancing on His breast and performing the creative, preservative and destructive processes. When there is neither light nor darkness, neither form nor energy, neither sound nor matter, when there is no manifestation of phenomenal existence, Shiva alone exists in Himself. He is timeless, spaceless, birthless, deathless, decayless. He is beyond the pairs of opposites. He is the Impersonal Absolute Brahman. He is untouched by pleasure and pain, good and evil. He cannot be seen by the eyes but He can be realised within the heart through devotion and meditation. Shiva is also the Supreme personal God when He is identified with His power. He is then omnipotent, omniscient active God. He dances in supreme joy and creates, sustains and destroys with the rhythm of His dancing movements. DR.RUPNATHJI( DR.RUPAK NATH ) He destroys all bondage, limitation and sorrow of His devotees. He is the giver of Mukti or the final emancipation. -

The Serpent Power by Woodroffe Illustrations, Tables, Highlights and Images by Veeraswamy Krishnaraj

The Serpent Power by Woodroffe Illustrations, Tables, Highlights and Images by Veeraswamy Krishnaraj This PDF file contains the complete book of the Serpent Power as listed below. 1) THE SIX CENTRES AND THE SERPENT POWER By WOODROFFE. 2) Ṣaṭ-Cakra-Nirūpaṇa, Six-Cakra Investigation: Description of and Investigation into the Six Bodily Centers by Tantrik Purnananda-Svami (1526 CE). 3) THE FIVEFOLD FOOTSTOOL (PĀDUKĀ-PAÑCAKA THE SIX CENTRES AND THE SERPENT POWER See the diagram in the next page. INTRODUCTION PAGE 1 THE two Sanskrit works here translated---Ṣat-cakra-nirūpaṇa (" Description of the Six Centres, or Cakras") and Pādukāpañcaka (" Fivefold footstool ")-deal with a particular form of Tantrik Yoga named Kuṇḍalinī -Yoga or, as some works call it, Bhūta-śuddhi, These names refer to the Kuṇḍalinī-Śakti, or Supreme Power in the human body by the arousing of which the Yoga is achieved, and to the purification of the Elements of the body (Bhūta-śuddhi) which takes place upon that event. This Yoga is effected by a process technically known as Ṣat-cakra-bheda, or piercing of the Six Centres or Regions (Cakra) or Lotuses (Padma) of the body (which the work describes) by the agency of Kuṇḍalinī- Sakti, which, in order to give it an English name, I have here called the Serpent Power.1 Kuṇḍala means coiled. The power is the Goddess (Devī) Kuṇḍalinī, or that which is coiled; for Her form is that of a coiled and sleeping serpent in the lowest bodily centre, at the base of the spinal column, until by the means described She is aroused in that Yoga which is named after Her. -

Hymn to Kālī Karpūrādi-Stotra By

HYMN TO K ĀLĪ KARP ŪRĀDI-STOTRA BY ARTHUR AVALON (Sir John Woodroffe ) WITH INTRODUCTION AND COMMENTARY BY VIMAL ĀNANDA-ŚVĀMĪ (Tantrik Texts Series, No. IX) London, Luzac & Co., [1922] PUBLISHERS' NOTE The Orientalists’ system of transliteration has been followed in this work. p. 1 PREFACE THIS celebrated Kaula Stotra , which is now translated from the Sanskrit for the first time, is attributed to Mah ākāla Himself. The Text used is that of the edition published at Calcutta in 1899 by the Sanskrit Press Depository, with a commentary in Sanskrit by the late Mah āmahop ādhy āya K ṛṣ hṇan ātha Ny āya-pañc ānana, who was both very learned in Tantra-Śā stra and faithful to his Dharma. He thus refused the offer of a good Government Post made to him personally by a former Lieutenant-Governor on the ground that he would not accept money for imparting knowledge. Some variants in reading are supplied by this commentator. I am indebted to him for the Notes, or substance of the notes, marked K. B. To these I have added others, both in English and Sanskrit explaining matters and allusions familiar doubtless to those for whom the original was designed, but not so to the English or even ordinary Indian reader. I have also referred to the edition of the Stotra published by Ga ṇeśa-Candra-Gho ṣa at Calcutta in 1891, with a translation in Bengali by Gurun ātha Vidy ānidhi, and commentary by Durg ārāma-Siddh āntav āgīś a Bhatt ācārya. I publish for the first time Vimal ānanda-Sv āmī's Commentary to which I again refer later. -

Shakti and Shkta

Shakti and Shâkta Essays and Addresses on the Shâkta tantrashâstra by Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), London: Luzac & Co., [1918] Table of Contents Chapter One Indian Religion As Bharata Dharma ........................................................... 3 Chapter Two Shakti: The World as Power ..................................................................... 18 Chapter Three What Are the Tantras and Their Significance? ...................................... 32 Chapter Four Tantra Shastra and Veda .......................................................................... 40 Chapter Five The Tantras and Religion of the Shaktas................................................... 63 Chapter Six Shakti and Shakta ........................................................................................ 77 Chapter Seven Is Shakti Force? .................................................................................... 104 Chapter Eight Cinacara (Vashishtha and Buddha) ....................................................... 106 Chapter Nine the Tantra Shastras in China................................................................... 113 Chapter Ten A Tibetan Tantra ...................................................................................... 118 Chapter Eleven Shakti in Taoism ................................................................................. 125 Chapter Twelve Alleged Conflict of Shastras............................................................... 130 Chapter Thirteen Sarvanandanatha ............................................................................. -

Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Anthropology - Dissertations Affairs 12-2011 Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition Jishnu Shankar Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Shankar, Jishnu, "Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition" (2011). Anthropology - Dissertations. 93. https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd/93 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Aghoreshwar Mahaprabhu Baba Bhagawan Ram Ji, a well-established saint of the holy city of Varanasi in north India, initiated many changes into the erstwhile Aghor tradition of ascetics in India. This tradition is regarded as an ancient system of spiritual or mystical knowledge by its practitioners and at least some of the practices followed in this tradition can certainly be traced back at least to the time of the Buddha. Over the course of the centuries practitioners of this tradition have interacted with groups of other mystical traditions, exchanging ideas and practices so that both parties in the exchange appear to have been influenced by the other. Naturally, such an interaction between groups can lead to difficulty in determining a clear course of development of the tradition. In this dissertation I bring together micro-history, hagiography, folklore, religious and comparative studies together in an attempt to understand how this modern day religious-spiritual tradition has been shaped by the past and the role religion has to play in modern life, if only with reference to a single case study. -

Shiva Is the Ultimate Outlaw

SHIVA Ultimate Outlaw Sadhguru Breaking the laws of physical nature is spiritual process. In this sense, we are outlaws, and Shiva is the ultimate outlaw. You cannot worship Shiva, but you may join the Gang. - Sadhguru Shiva – Ultimate Outlaw Sadhguru ©2014 Sadhguru First Edition: February 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Cover design, typesetting, book layout and compilation done by the Archives of Isha Yoga Center. All photographs used in this book are the copyrighted property of Isha Foundation, unless otherwise noted. Published by: Isha Foundation 15, Govindasamy Naidu Layout, Singanallur, Coimbatore - 641 005 INDIA Phone: +91-422-2515345 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents ◊ Who is Shiva? 3 ◊ Dawn of Yoga 7 The Presence of Shiva 10 ◊ Kailash – Mystic Mountain 15 ◊ Velliangiri – Kailash of the South 16 ◊ Kashi – Eternal City 21 ◊ Kantisarovar – Lake of Grace 26 Shiva’s Adornments 32 ◊ Third Eye 34 ◊ Nandi 35 ◊ Trishul 37 ◊ Moon 38 ◊ Serpent 40 Ultimate Outlaw 42 SHIVa – UlTIMAte OUtlaW 1 here is a beautiful incident that happened when Shiva and Parvati were to be married. Theirs was to be the greatest Tmarriage ever. Shiva – the most intense human being that anyone could think of – was taking another being as a part of his life. Everyone who was someone and everyone who was no one turned up. All of the devas and divine beings were present, but so were all the asuras or demons.