The Mass Strike of 1917 in Eastern Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perth Strike 1897

1 William H ‘Bill’ Mellor and the Perth- Fremantle building trades strikes of 1896-97 11,598 words/ 16,890 with notes When Bill Mellor lost his footing on a ten-metre scaffold in 1897, that misstep cost him his life, his wife and three children their provider, the Builders’ Labourers’ Society in Western Australia its most energetic official, and socialism a champion. On Thursday, 11 June, the 35-year old Mellor had been working on the Commercial Union Assurance offices on St Georges Terrace when he tumbled backwards, breaking his back, to die in hospital a few hours later.1 In the days that followed, the labour movement rallied to support Mellor’s family. Bakers, boot-makers, printers and tailors sent subscription lists around their workplaces;2 the donations from twenty building jobs totaled £174 9s 4d, while Mellor’s employer and associates contributed £50.3 The Kalgoorlie and Boulder Workers Association forwarded their collections with notes of appreciation for Mellor’s organising in Melbourne and Sydney.4 The Perth and Fremantle Councils provided their Town Halls without charge for benefit concerts.5 The Relief Fund realised £45 from the sale of Mellor’s house and allotment, in Burt Street, Forrest Hill, a housing estate in North Perth.6 The Fund’s trustees paid out £15 on the funeral, to which a florist donated wreaths,7 while a further 1 West Australian (WA), 10 June 1897, p. 4; the building opened in December, WA, 2 December 1897, p. 3. 2 WA, 29 June 1897, p. 4, 6 July 1897, p. -

Anarchism in Australia

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchism in Australia Bob James Bob James Anarchism in Australia 2009 James, Bob. “Anarchism, Australia.” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, edited by Immanuel Ness, 105–108. Vol. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Gale eBooks (accessed June 22, 2021). usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2009 James, B. (Ed.) (1983) What is Communism? And Other Essays by JA Andrews. Prahran, Victoria: Libertarian Resources/ Backyard Press. James, B. (Ed.) (1986) Anarchism in Australia – An Anthology. Prepared for the Australian Anarchist Centennial Celebra- tion, Melbourne, May 1–4, in a limited edition. Melbourne: Bob James. James, B. (1986) Anarchism and State Violence in Sydney and Melbourne, 1886–1896. Melbourne: Bob James. Lane, E. (Jack Cade) (1939) Dawn to Dusk. N. P. William Brooks. Lane, W. (J. Miller) (1891/1980) Working Mans’Paradise. Syd- ney: Sydney University Press. 11 Legal Service and the Free Store movement; Digger, Living Day- lights, and Nation Review were important magazines to emerge from the ferment. With the major events of the 1960s and 1970s so heavily in- fluenced by overseas anarchists, local libertarians, in addition Contents to those mentioned, were able to generate sufficient strength “down under” to again attempt broad-scale, formal organiza- tion. In particular, Andrew Giles-Peters, an academic at La References And Suggested Readings . 10 Trobe University (Melbourne) fought to have local anarchists come to serious grips with Bakunin and Marxist politics within a Federation of Australian Anarchists format which produced a series of documents. Annual conferences that he, Brian Laver, Drew Hutton, and others organized in the early 1970s were sometimes disrupted by Spontaneists, including Peter McGre- gor, who went on to become a one-man team stirring many national and international issues. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples. -

Opening Pages (PDF)

Editors Rick Kuhn Tom O’Lincoln Editorial board John Berg, Suffolk University Tom Bramble, University of Queensland Verity Burgmann, University of Melbourne Gareth Dale, Brunel University Bill Dunn, University of Sydney Carole Ferrier, University of Queensland Diane Fieldes, Sydney Phil Gasper, Madison Area Technical College Phil Griffiths, University of Southern Queensland Sarah Gregson, University of New South Wales Esther Leslie, Birkbeck College John Minns, Australian National University Georgina Murray, Griffith University Bertell Ollman, New York University Liz Reed, Monash University Brian Roper, University of Otago Jeff Sparrow, Overland/Victoria University Ian Syson, Victoria University Submission Articles are generally about 7,000 words long but may be significantly shorter or more extensive, depending on the nature of the material and topics. Material is be published after a double-blind review process. For more details see the web site. www.anu.edu.au/polsci/mi marxistinterventions @ gmail.com ISSN: 1836-6597 Cover design Daniel Lopez Contents From the editors 5 The fire last time: the rise of class struggle and progressive social movements in Aotearoa/New Zealand, 1968 to 1977 Brian S. Roper 7 Financial fault lines Ben Hiller 31 Contributors Ben Hillier is a member of Socialist Alternative. He is a contributor to sa.org.au and Marxist Left Review. Brian Roper teaches Politics at the University of Otago, is a founding member of the International Socialist Organisation (NZ), and has been a political activist in New Zealand since the early 1980s. His most recent book is Prosperity for all? Economic, social and political change in New Zealand since 1935, Thomson, Southbank, 2005). -

A Paperback Education: Out-Kick and Out-Run Me

ENDNOTES 100 per cent in his Latin exam; (it that through both the guidance he was later rumoured that he provides for Jem and Scout and 1. Katharine Susannah Prichard, cheated, but as the exam was an the understanding, even tender- Coonardoo, Pacific Books, oral it seems hardly possible). He ness that he displays toward Boo Sydney, 1971 (1929), p.198. struggled with most other subjects Radley, Atticus is attempting to 2. R. Rorty, Contingency, Irony and Solidarity, CUP, New York, 1989, though, with English Literature live a moral life, which of itself is a p.xvi. being his nemesis. somewhat over-inflated liberal 3. Drusilla Modjeska, ‘Introduction’ Forever determined to estab- notion considering the level of in Coonardoo, A&R, Sydney, lish difference between myself and violence being acted out against 1993, p.vi. my brother, literature became my the black community around him 4. Susan Lever, Real Relations: The Politics of Form in Australian thing. I read every Penguin at the time.” Fiction, Halstead Press in ‘classic’ and modern ‘master- “Does Camus encourage the association with ASAL, Sydney, piece’ that he was set during high reader to see Meursault as a 2000, p.61. school. I cruised through Dickens nihilistic character or do we and Hardy before moving on to actually come to value the need Enza Gandolfo is a Melbourne the modernists, devouring Harper for an ethical life through his writer and a PhD student at Victoria Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, vacuous state of mind?” University. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye This was a difficult one to (naturally), and one of my all- answer. -

The Rise and Fall of Australian Maoism

The Rise and Fall of Australian Maoism By Xiaoxiao Xie Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Studies School of Social Science Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide October 2016 Table of Contents Declaration II Abstract III Acknowledgments V Glossary XV Chapter One Introduction 01 Chapter Two Powell’s Flowing ‘Rivers of Blood’ and the Rise of the ‘Dark Nations’ 22 Chapter Three The ‘Wind from the East’ and the Birth of the ‘First’ Australian Maoists 66 Chapter Four ‘Revolution Is Not a Dinner Party’ 130 Chapter Five ‘Things Are Beginning to Change’: Struggles Against the turning Tide in Australia 178 Chapter Six ‘Continuous Revolution’ in the name of ‘Mango Mao’ and the ‘death’ of the last Australian Maoist 220 Conclusion 260 Bibliography 265 I Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. -

The Railway Line to Broken Hill

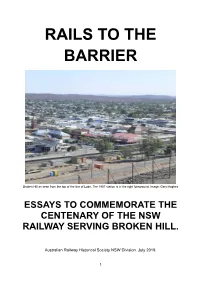

RAILS TO THE BARRIER Broken Hill as seen from the top of the line of Lode. The 1957 station is in the right foreground. Image: Gary Hughes ESSAYS TO COMMEMORATE THE CENTENARY OF THE NSW RAILWAY SERVING BROKEN HILL. Australian Railway Historical Society NSW Division. July 2019. 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 3 HISTORY OF BROKEN HILL......................................................................... 5 THE MINES................................................................................................ 7 PLACE NAMES........................................................................................... 9 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE....................................................................... 12 CULTURE IN THE BUILDINGS...................................................................... 20 THE 1919 BROKEN HILL STATION............................................................... 31 MT GIPPS STATION.................................................................................... 77 MENINDEE STATION.................................................................................. 85 THE 1957 BROKEN HILL STATION................................................................ 98 SULPHIDE STREET STATION........................................................................ 125 TARRAWINGEE TRAMWAY......................................................................... 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................... -

Albert Morris and the Broken Hill Regeneration Area: Time, Landscape and Renewal

Albert Morris and the Broken Hill regeneration area: time, landscape and renewal By Peter J Ardill July, 2017i Contents: 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………….2 2. Degraded landscapes: 1900-1936…….……………………………………………………3 3. Plantation projects: 1936-1938…………………………………………..………………..13 4. Regeneration projects: 1936-1939………………………………………………………..17 5. War, consolidation and evaluation: 1939-1945……………………………………..29 6. Completion of the Broken Hill regeneration area: 1946-1958………….…….32 7. Appraisal of the Broken Hill regeneration area.........................................35 Epilogue, Acknowledgements, Disclaimer………………………………………………….40 Cited References……………………………………………………………………………………….41 Appendix A. Chronology…………………………………………………………………………….46 Appendix B. Map ………………………………………………………………………………………56 Citation, End-notes ….………………………………………………………………………………57 Note: Second edition, published October 2017. Minor typographical and format corrections. Reader advice box removed. Third edition, published September 2018. Minor typographical corrections. ISBN added. Albert Morris and the Broken Hill regeneration area - July 2017 The traditional occupation of their lands, dispossession and future of the Wilyakali People are acknowledged. _____________________ 1. Introduction The City of Broken Hill is now completely surrounded by areas specially reserved for regeneration of vegetation (Wetherell 1958) In a statement dated Wednesday, the 15th of October, 1958, the New South Wales Minister for Conservation, Ern Wetherell, announced the completion of the construction -

Jeff Sparrow Onkilling P9

FREE JULY 2009 Readings Monthly your independent book, music and dVd newsletter • eVents • new releases • reViews ) SEE PAGE 9 ) SEE PAGE P U M ( NG ILLI K IMAGE FROM JEFF SP[ARROW'S NEW BOOK Jeff Sparrow on Killing p 9 July book, CD & DVD new releases. More July new releases inside. FICTION FICTION FICTION NON-FICTION NON-FICTION DVD POP CD CLASSICAL $32.95 $27.95 $32.95 $29.99 $32.99 $35 $34.95 $29.95 $21.95 $34.95 >> p4 >> p5 >> p6 >> p9 >> p10 >> p16 >> p17 >> p19 July Event Highlights at Readings. See more Readings events inside. ANDY GRIFFITHS HELEN GARNER BRIAN CASTRO ANNE SUMMERS AT WESTGARTH AT READINGS AT READINGS AT READINGS THEATRE, HAWTHORN CARLTON HAWTHORN NORTHCOTE All shops open 7 days. Carlton 309 Lygon St 9347 6633 Hawthorn 701 Glenferrie Rd 9819 1917 Malvern 185 Glenferrie Rd 9509 1952 Port Melbourne 253 Bay St 9681 9255 St Kilda 112 Acland St 9525 3852 State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston Street 8664 7560 email [email protected] Find information about our shops, check event details and browse or shop online at www.readings.com.au 2 Readings Monthly July 2009 From the Editor ‘MagiCAL’ review ThisNEW-LOOK Month’sMARILYNNE News ROBINSON LORD MAyor’s CreaTIVE FOR HOUSE OF EXILE READINGS MONTHLY WINS ORANGE WRITING AWARDS Evelyn Juers must be Readings Monthly has had a makeover! Our The Orange Prize for the best novel written The City of Melbourne and Melbourne delighted with the rave new tabloid format, printed by The Age, gives by a woman was awarded to Marilynne Rob- Library Service are proud to announce the review her book The House us the space for more news, reviews and fea- inson’s Home (Virago, PB, $25), in a unani- inaugural Lord Mayor’s Creative Writing of Exile (Giramondo, PB, tures – and what's more, we're now printed mous decision by the judges. -

George SHIELL,Raymond Joseph BUTTEL,Peter S BALL,Angela

George SHIELL 08/12/2016 George SHIELL ( late of Sorrell-street, Parramatta ) New South Wales Police Force Regd. # ? Rank: Constable 1st Class – appointed December 1902 Stations: Lawson, Broken Hill, Parramatta Police Service: From 2 January 1891 to 7 December 1912 = 22 years Service Awards: ? Born: ? ? 1860 Event location: Pennant Hills Rd, Parramatta Event date: 27 November 1912 about 9pm Died on: Saturday 7 December 1912 at Parramatta Hospital having never regained consciousness since being struck ON Duty Age: 43 Cause: Traffic Accident – Pedestrian – Concussion of the brain Funeral date: Monday 9 December 1912 between 11.30am – 2pm Funeral location: From Parramatta Hospital, past Parramatta Police Stn Buried at: Presbyterian section, Mays Hill Cemetery, cnr Great Western Hwy & Steele St, Parramatta Memorial at: ? [alert_red]GEORGE is NOT mentioned on the Police Wall of Remembrance[/alert_red] * BUT SHOULD BE [divider_dotted] FURTHER INFORMATION IS NEEDED ABOUT THIS PERSON, THEIR LIFE, THEIR CAREER AND THEIR DEATH. PLEASE SEND PHOTOS AND INFORMATION TO Cal [divider_dotted] May they forever Rest In Peace [divider_dotted] The constable was knocked down by a young man riding a bicycle in Pennant Hills Road, Parramatta on 27 November, 1912. He was taken to the Parramatta Hospital where he passed away on 7 December. He was on duty at the time. The following brief article appeared in the Barrier Miner newspaper of the 9 December, 1912. “DEATH OF A CONSTABLE – RESULT OF A BICYCLE COLLISION. On November 27 Constable G. Sheill [sic], while on duty on the Pennant Hills Road, was run into from behind by a cyclist named Francis Mobbs, who was on his way to the chemists for medicine for a sick relative. -

Chummy Flemming

€' ?" .|II,__ ._,._ 1|.-_. A4-."-:'~';.-"..’.-'fi"~,1."3 MOHTU MlL>L>€R I3T{€é@3 CHU1§/IMY_FLEMING Willi Box 92 Broadway. Sydn€y ZOO? Australm Pg-;:-I’/\;\_\_Va a br1ef b1ography CHU1§/IMY_FLEMING a br1ef b1ography I 1 | i : 1 1 i 1 BOB JAMES i 1 1 MONTY MILLER PRESS Sydney LIBERTARIAN RESOURCES Melbourne _ J — "' T" — — ii? John Fleming, generally known as 'Chummy', was born in 1863 in Derby, England, the son of an Irish father and an English mother who died when JW was five years old. His (maternal) grandfather had- been an 'agltator' in the Corn Laws struggle and his father also had been involved In Derby strikes.‘ '...At 10 he had to go to work in a Leicester boot factory. The confinement and toil broke down the boy's health and whilst laid up with sickness he began to reflect and to feel that he was a sufferer from social Injustice...‘ Fleming attended the free thought lectures of Bradiaugh, Holyoake and Annie Besant, before coming to Melbourne. Jack Andrews, an anarchist colleague, recorded his early period in Australia this way:2 '...(He was) 16 when his uncle invited him to Melbourne. He arrived in 1884 and for a time he was a good deal more prosper- ous than later, getting work as a bootmaker'. CHUMMY FLEMING : A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY He attended the 1884 (2nd Annual) Secular Conference held in Sydney, but more importantly was soon regularly attending the North Bob James Wharf Sunday afternoon meetings, illegally selling papers there. The regular speakers at the time were Joseph Symes, President of the Australasian Secular Association, Thomas Walker, another free thought lecturer, Monty Miller, a veteran radical, and W.A.