Go, Tell Michelle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Presidential Politics of Aaron Sorkin's the West Wing

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2019 "Let Bartlet Be Bartlet:" The rP esidential Politics of Aaron Sorkin's The esW t Wing Marjory Madeline Zuk [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Zuk, Marjory Madeline, ""Let Bartlet Be Bartlet:" The rP esidential Politics of Aaron Sorkin's The eW st Wing" (2019). Honors Theses. 493. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/493 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 2 I would like to thank my wonderful advisor, Professor Meinke, for all of his patience and guidance throughout this project. I so appreciate his willingness to help me with this process – there is no way this thesis would exist without him. Thank you for encouraging me to think deeper and to explore new paths. I will miss geeking out with you every week. I would also like to thank my friends for all of their love and support as I have slowly evolved into a gremlin who lives in Bertrand UL1. I promise I will be fun again soon. I would like to thank my professors in the Theatre department for all of their encouragement as I’ve stepped out of my comfort zone. Thank you to my dad, who has answered all of my panic-induced phone calls and reminded me to rest and eat along the way. -

Post-Presidential Speeches

Post-Presidential Speeches • Fort Pitt Chapter, Association of the United States Army, May 31, 1961 General Hay, Members of the Fort Pitt Chapter, Association of the United States Army: On June 6, 1944, the United States undertook, on the beaches of Normandy, one of its greatest military adventures on its long history. Twenty-seven years before, another American Army had landed in France with the historic declaration, “Lafayette, we are here.” But on D-Day, unlike the situation in 1917, the armed forces of the United States came not to reinforce an existing Western front, but to establish one. D-Day was a team effort. No service, no single Allied nation could have done the job alone. But it was in the nature of things that the Army should establish the beachhead, from which the over-running of the enemy in Europe would begin. Success, and all that it meant to the rights of free people, depended on the men who advanced across the ground, and by their later advances, rolled back the might of Nazi tyranny. That Army of Liberation was made up of Americans and Britons and Frenchmen, of Hollanders, Belgians, Poles, Norwegians, Danes and Luxembourgers. The American Army, in turn, was composed of Regulars, National Guardsmen, Reservists and Selectees, all of them reflecting the vast panorama of American life. This Army was sustained in the field by the unparalleled industrial genius and might of a free economy, organized by men such as yourselves, joined together voluntarily for the common defense. Beyond the victory achieved by this combined effort lies the equally dramatic fact of achieving Western security by cooperative effort. -

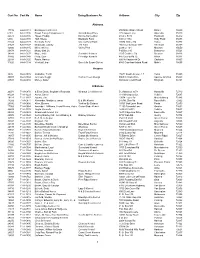

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

Michelle Obama Talks Gun Violence with Students at Home in Chicago by Chicago Tribune, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 04.12.13 Word Count 984

Michelle Obama talks gun violence with students at home in Chicago By Chicago Tribune, adapted by Newsela staff on 04.12.13 Word Count 984 First lady Michelle Obama speaks at an event bringing her "Let's Move" campaign to Chicago's public schools on Feb. 28, 2013. Photo: Abel Uribe/Chicago Tribune/MCT As politicians in Washington took a step toward tightening the nation's gun laws on Wednesday, first lady Michelle Obama sat down with Chicago high school students whose stories about violence brought her to tears. Before the meeting began at Harper High School, Obama said she wanted to hear from each of the 22 students representing youth programs at the school and that she had as much time as they needed to take. She had come home to Chicago, she said, to do a lot of listening. So for two hours, the first lady sat in the second-floor library, away from the news media, as students told story after story about the challenges of dodging bullets, avoiding gangs and – the thing they cannot take for granted – staying alive. A Tearful Meeting According to the students, the first lady wanted to know how many of them had been affected by gun violence. Every one of them told her they had, said Ta'taleisha Jones, a 16-year-old who attended the meeting. "She said, 'Have you ever experienced a family member hurt or killed?' I told her, 'Yeah.' When she was talking about how her life was and how we changed her, she got real emotional. -

![“The California 47Th” [Intro Music] JOSH: You're Listening to the West](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0514/the-california-47th-intro-music-josh-youre-listening-to-the-west-3190514.webp)

“The California 47Th” [Intro Music] JOSH: You're Listening to the West

The West Wing Weekly 4.16: “The California 47th” [Intro Music] JOSH: You’re listening to The West Wing Weekly. I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. Today we’re talking about “The California 47th”. It’s episode 16 of season 4. JOSH: The teleplay is by Aaron Sorkin, the story by Lauren Schmidt and Paula Yoo. It was directed by Vincent Misiano, and it first aired in the year 2003 on the nineteenth day of Solmonath, which of course is the second month according to the Anglo Saxon Heathen calendar, as described by the Venerable Bede in his 8th Century classic, De temporum ratione. By the way, my own mom’s birthday is the 19th of Solmonath. HRISHI: [laughing] Happy Birthday. JOSH: Happy Birthday Fran. Schizo-fran-ic. HRISHI: We’re synced up with the series right now, because today we’re recording this in February; Toby mentions that the weather is 74 degrees in California, and it is 72 degrees as we speak. JOSH: Oh nice. That is the daily weather report on local news. It’s sunny and 72. HRISHI: Mmm hmm. Here’s a little synopsis. This episode really takes place in three different locations, although we only see two of them on screen. Equatorial Kundu, Washington D.C., and Orange County. JOSH: Yes. HRISHI: As from the Situation Room, Leo and the president monitor the situation in Bitanga, and in Orange County, the president travels with his retinue to go help out Sam - hopefully help out Sam - on his campaign trail. JOSH: Yes. -

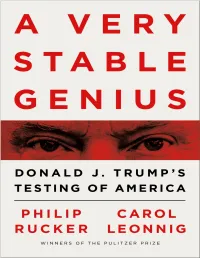

A Very Stable Genius at That!” Trump Invoked the “Stable Genius” Phrase at Least Four Additional Times

PENGUIN PRESS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2020 by Philip Rucker and Carol Leonnig Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952799 ISBN 9781984877499 (hardcover) ISBN 9781984877505 (ebook) Cover design by Darren Haggar Cover photograph: Pool / Getty Images btb_ppg_c0_r2 To John, Elise, and Molly—you are my everything. To Naomi and Clara Rucker CONTENTS Title Page Copyright Dedication Authors’ Note Prologue PART ONE One. BUILDING BLOCKS Two. PARANOIA AND PANDEMONIUM Three. THE ROAD TO OBSTRUCTION Four. A FATEFUL FIRING Five. THE G-MAN COMETH PART TWO Six. SUITING UP FOR BATTLE Seven. IMPEDING JUSTICE Eight. A COVER-UP Nine. SHOCKING THE CONSCIENCE Ten. UNHINGED Eleven. WINGING IT PART THREE Twelve. SPYGATE Thirteen. BREAKDOWN Fourteen. ONE-MAN FIRING SQUAD Fifteen. CONGRATULATING PUTIN Sixteen. A CHILLING RAID PART FOUR Seventeen. HAND GRENADE DIPLOMACY Eighteen. THE RESISTANCE WITHIN Nineteen. SCARE-A-THON Twenty. AN ORNERY DIPLOMAT Twenty-one. GUT OVER BRAINS PART FIVE Twenty-two. AXIS OF ENABLERS Twenty-three. LOYALTY AND TRUTH Twenty-four. THE REPORT Twenty-five. THE SHOW GOES ON EPILOGUE Acknowledgments Notes Index About the Authors AUTHORS’ NOTE eporting on Donald Trump’s presidency has been a dizzying R journey. Stories fly by every hour, every day. -

How OFAC's Regulatory Changeup Enables Cuban Baseball Player Smuggling to the United States

COMMENTS YOU’RE OUT: HOW OFAC’S REGULATORY CHANGEUP ENABLES CUBAN BASEBALL PLAYER SMUGGLING TO THE UNITED STATES ROBYN C. SCHOWENGERDT* INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 306 I. DEVELOPMENTS IN U.S.–CUBA RELATIONS UNDER THE EMBARGO ........................................................................................... 308 II. UP TO BAT:MLB,CBF, AND THEIR PLAYERS ................................. 311 A. Player Smuggling: Problems and Proposed Solutions .......................... 311 B. The MLB–CBF Deal ................................................................. 315 III.HOW THE UNITED STATES REGULATES CUBA SANCTIONS ............ 317 A. The Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) ................................... 317 B. Cuba Sanctions Under Trump ....................................................... 319 IV.STRIKE OUT, OR SOLUTIONS? .......................................................... 322 A. Judicial Review .......................................................................... 322 B. CACR Regulatory Interpretation .................................................... 329 C. Agency Coordination and Congress ................................................. 335 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................... 335 * J.D. Candidate, American University Washington College of Law (2021); B.A., International Studies, American University (2014). Thank you to my family for their unconditional love and support, -

“Transition” Guest: Bradley Whitford

The West Wing Weekly 7.19: “Transition” Guest: Bradley Whitford [Intro Music] JOSH: Josh and Hrishi here. As you’ve probably noticed from the title of this episode we recorded this live in front of an audience in London. HRISHI: The show opens with a performance by cellist Adrian Bradbury. JOSH: Here we go… [Opens with Adrian Bradbury playing the Prelude from Bach’s Cello Suite No.1] [Audience applauds] JOSH: Hey Hrishi, travelling across the Atlantic to discuss a single episode of a twenty-year old show. In front of people who’ve paid good money for a standing room, obstructed view ticket. [Cheers from audience] It sounds crazy, no? HRISHI: It does, Josh. It does. But here in our little village of The West Wing Weekly, every one of us is a fiddler on the roof. We’re just trying to watch our show without breaking our necks. Why do we watch it over and over again? That I can tell you in one word… BRAD: [To the tune of “Tradition” from Fiddler on the Roof] Transition! Transition! [Audience cheers] HRISHI & JOSH: Transition! HRISHI: Live from the Hammersmith Apollo, this is The West Wing Weekly. I’m Hrishikesh Hirway… JOSH: And I’m Joshua Malina. And this is… BRAD: Television’s Bradley Whitford. JOSH: Inexplicable Three-time Emmy winner, Brad Whitford! And we are here to discuss.. HRISHI: Episode 19 from Season 7. It’s called “Transition.” Oh, excuse me, it’s called… [To the tune of “Tradition” from Fiddler on the Roof] ALL: Transition! JOSH: It was written by Peter Noah, it was directed by Nelson McCormick, I can’t find my notes so I’m going to make up a date. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks at a St. Patrick's Day Reception March 15, 2016

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks at a St. Patrick's Day Reception March 15, 2016 Vice President Joe Biden. Hello, folks! Welcome to the White House. How are you? Good to see you; it's a beautiful dress. Folks, my name is Joe Biden. I work for Barack Obama. And I have the great honor of introducing our next three guests. In 1963, President Kennedy addressed the Irish Parliament and said, and I quote, "Our two nations, divided by distance, have been united by history." Today we celebrate that shared heritage that has defined so many of us and—as individuals, and it's defined our country as well. And it's clear why this day is so important to many of you and to me and the President, who have ancestors who are from Ireland, who left behind everything to find a new home and find a place in that Promised Land, America. In the face of oppression, they held strong, strong, strong beliefs. They planted deep roots, and they looked to the future. It's the immigrant story of all who came here. And the truth is that the greatest contribution the Irish brought to this country is a set of values: hard work, family, a sense of community, pride, faith, and idealism. My mother had an expression—and I mean this sincerely—she talked about, being Irish was about family, faith, but most of all, it was about courage. She said, because without courage, you cannot love with abandon. And to be Irish is to be able to love with abandon, to be able to dream. -

Fall 2010, Volume 122, No

– The Sound of a Century – nOn-prOfiT U.s. pOsTage paiD perMiT #108 sparTanBUrg, sC 29301 580 East Main Street Spartanburg, South Carolina 29302 www.converse.edu Petrie 100 Years of World School of Music Class Music Reunion October 28-30, 2010 Including The Petrie School of Music Centennial Celebration Reunion Musical Mentors Weekend April 15-16, 2011 Class Years Ending in 1 & 6, The Class of 2010 and the Golden Club Info & Registration: Converse.edu/Reunion Collaborations Help spread the word about our NEW scholarship program! The Sounds of a Century THE CONVERSE COMMITMENT 1910 - 2010 Petrie School of Music Centennial Celebration Concert At Converse, High School Achievement = BIG BUCKS We reward students’ hard work by investing in their future. Thursday, October 28, 2010 1200 SAT & 3.5 GPA $18,000 Presidential Scholar 7:30 PM 1100 SAT & 3.0 GPA $15,000 Converse Scholar Twichell Auditorium free admission (no ticket required) 1000 SAT & 3.0 GPA $12,000 Tower Scholar dessert reception to follow in Wilson Hall 900 SAT & 3.0 GPA $9,000 Merit Scholar ACCOMMODATIONS Converse Room Blocks Available Our new net cost calculator takes the guesswork out of determining Spartanburg Marriott at Renaissance Park (800.327.6465) scholarship and financial aid awards. Students can etg to the bottom Courtyard Marriott (800.321.2211) line at converse.edu/TheConverseCommittment. Apply online at converse.edu/apply Early Action November 15, 2010 Regular Decision March 15, 2011 Wael Farouk Elizabeth Child Kimilee Bryant Richard Troxell Ann Ratteree Herlong Anna -

Parks and Recreation Special Guests: Rob Lowe, Adam Scott, and Michael Schur

The West Wing Weekly 0.07: Parks and Recreation Special Guests: Rob Lowe, Adam Scott, and Michael Schur HRISHI: You’re listening to a special episode of The West Wing Weekly. Today, we’re talking about all the ways in which The West Wing helped influence another show about idealistic people in government: Parks and Recreation. JOSH: Parks and Rec aired on NBC from 2009 to 2015, was nominated for loads of Emmys and a couple of Golden Globes, including a win for its star Amy Poehler in the role of Leslie Knope who, frankly, would have done very well in the Bartlet administration. HRISHI: If you haven’t seen Parks and Rec: one, get on it because you’re missing out, and two if you want a quick crash course before you keep listening to this episode, press pause here and then we recommend you watch, at a bare minimum, the last two episodes of Season 2, plus the “Live Ammo” episode which is Season 4, Episode 19. JOSH: This is an amazing show and if you can’t be bothered to watch all of it, well God, Jed, I don’t even wanna know you. HRISHI: There are two parts to our conversation today. We spoke with the co-creator of the show, Michael Schur, who is also responsible for creating or co-creating a bunch of great TV shows: the American version of The Office and then Parks and Rec, followed by Brooklyn 99, and then most recently, The Good Place. Some of the best TV around. -

Inc. Magazine New York, New York 20 June 2017

U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, Inc. New York, New York Telephone (917) 453-6726 • E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cubatrade.org • Twitter: @CubaCouncil Facebook: www.facebook.com/uscubatradeandeconomiccouncil LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/u-s--cuba-trade-and-economic-council-inc- Inc. Magazine New York, New York 20 June 2017 Trump's Cuba Moves 'An Epic Disaster' for Entrepreneurs Renewed ties were supposed to lead to economic progress. And now it's all at a standstill. By David Whitford Editor-at-large CREDIT: Getty Images Last week, hopeful belief collided with hard fact. President Trump, as he promised he would during the campaign, began dismantling former President Obama's historic overture to Cuba. Before an adoring crowd in Miami's Little Havana, the U.S. President attacked his predecessor's "terrible and misguided deal with the Castro regime," promising that, "We will enforce the ban on tourism. We will enforce the embargo," and otherwise set about dismantling his predecessor's legacy. A particular target of Trump's new policy: U.S. dealings with companies tied to Cuba's military, which covers broad swathes of the tourist industry from nightclubs to hotels and resorts. This wasn't supposed to happen. At the end of 2014, Obama signed an executive order moving to officially open ties with the island nation; consequently all signs were pointing to a long-awaited thaw. Among other things, the U.S. would establish a diplomatic outpost in the country, Cuban businesses could export to the U.S. and U.S. companies could enter the Cuban market.